Beyond Open Access

Open Educational Resources for Legal Clarity, Sustainability, and Digital Sovereignty in European University Alliances

1 Introduction

Open educational resources (OER) are widely recognized for their role in enhancing access to education and facilitating knowledge sharing. Defined by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2019) as “teaching, learning, and research materials in any medium – digital or otherwise – that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits no-cost access, use, adaptation, and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions,” OER have become pivotal in global educational strategies.

Although the general benefits of OER, such as cost savings and improvements in teaching quality, are well acknowledged, their strategic advantages within European university alliances remain underexplored. The European university alliance initiative of the European Union was launched in 2017 to “foster open science practice, such as open access publishing, knowledge and data sharing, and open collaboration” (Council of the EU, 2021). The Graz University of Technology (TU Graz) is a partner in the Unite! (2025) alliance, one of the more than 70 European university alliances. The network includes eight fellow institutions: Technische Universität Darmstadt (Germany), Aalto University (Finland), Institut national polytechnique de Grenoble (France), KTH Royal Institute of Technology (Sweden), Politecnico d Torino (Italy), Universidade de Lisboa (Portugal), Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (Spain), and Wrocław University of Science and Technology (Poland). In the context of these European university alliances, which prioritize cross-border collaboration and sustainability, OER offer additional – and often overlooked – benefits. The present research aims to address this gap by focusing on three key areas where OER can contribute to international higher education collaboration and teaching: legal certainty, sustainability, and digital sovereignty.

The “Unite! OER Courses” project (10/2023 – 09/2024) within the Unite! seed fund initiative exemplifies cross-alliance collaboration on OER (Schön et al., 2025; Vicente-Sáez et al., 2024). This project revealed diverse levels of OER implementation among partner institutions. Some universities maintain their own OER repositories, while others are still in the early stages of adoption. At TU Graz, for instance, an OER strategy has been in place since 2020 (TU Graz, 2020), positioning the institution as a leader in national OER development. In 2025, TU Graz is expected to become the second Austrian public university to receive the national “Certified OER Higher Education Institution” certificate (see Schön et al., 2023).

We have encountered numerous arguments in support of OER in the course of our experiences. Through our work on the OER project within Unite! and the related publications, we have identified three aspects that have only recently begun to attract the attention of a limited number of stakeholders: legal certainty, sustainability, and digital sovereignty.

2 Development of Discussions and Research on OER Benefits

In this section, we briefly describe how the discourse around the benefits of OER has evolved and current research priorities in this field. According to the first European-funded research project on OER, olcos.org, from the perspective of European, national, and regional educational networks, OER provide a reusable, alliancebased framework that maximizes returns on publicfund investments by sharing development costs, enriches curricula with diverse cultural and informational resources, and elevates content quality through communitydriven feedback and qualitycontrol mechanisms. Simultaneously, OER boost digital competence, foster critical thinking and creativity, and promote lifelong learning and social inclusion by granting universal, lowcost access to highquality educational materials (Geser, 2007, p. 20).

Mora (2008) outlined the motivations of institutions to participate in OER projects identified in the literature. Based on contributions by authors such as Hylén (2006), she listed: “public relations and attract[ing] future students, ethical reasons, sharing knowledge is a good thing to do, cost reduction, creating alternatives to commercial materials, experimenting with new business models, encouraging innovation, quality enhancement and diversity, leverage taxpayer’s money” (p. 24, Table 6).

Butchers’ (2011) contribution is another early and thorough overview of the global situation. The paper’s discussion highlights that OER promotes costfree legal access to learning resources, enhances transparency and collaboration across institutions, supports educators by reducing workload pressure, is compatible with existing ICT infrastructures (including in developing regions), and cultivates a communitydriven economic model that shifts incentives toward sharing and collective knowledge creation.

In its “Opening up education” policy paper on OER, two years later, the European Commission (2013) spotlighted the following benefits: OER can dramatically broaden access to highquality learning materials, thereby lowering expenses for students, institutions, and public budgets while fostering inclusive, personalized, and collaborative education. By leveraging OER, Europe can accelerate digitalskill development and stimulate pedagogical innovation (e.g., blended and competencybased learning) while creating a transparent, interoperable ecosystem that supports crossborder cooperation and strengthens the region’s competitiveness in the global knowledge economy.

Further, a white paper from an Austrian working group on OER in higher education some years later (Ebner et al., 2016, p. 38) summarized arguments in favor of OER and OER policy in the following way: OER expand free, legal access to learning materials and enable easy reuse, adaptation, and collaborative pedagogical practices such as eportfolios, flipped classrooms, and gamebased learning; they also boost quality through public peer review, foster inclusive adaptations to diverse learners, and strengthen institutional reputation and partnerships while improving efficiency and innovation in highereducation teaching.

UNESCO’s (2019) recommendation on OER acknowledges that OER make learning instantly accessible to everyone, including people with disabilities and marginalized groups, while supporting personalized instruction, promoting gender equity, and encouraging innovative teaching methods (UNESCO, 2019, I, 3). The document argues that OER provide more cost-effective processes based on adaptable and inclusive educational resources that foster innovative teaching and empower learners to cocreate content. These resources also enable governments to meet policy goals more sustainably through collaborative creation, curation, and reuse (see UNESCO, 2019, II 5 – 8).

Otto et al.’s (2021) review of the evidencebased literature on OER indicates that the primary research agenda centers on how OER are perceived and integrated into teaching and learning contexts: researchers are beginning to examine open textbooks, especially their costsaving potential and how they qualitatively compare with conventional resources. For example, Hilton et al. (2019) examined how replacing commercial curriculum materials with OER influences elementaryschool students’ mathematics achievement. In a controlled stuy , reporting the effects observed in a controlled study they found no statistically significant difference in exam scores between students who used OER and those who used the commercial textbooks.

In recent years, publications on open educational practices have proliferated (see Bellinger & Mayrberger, 2019; Tlili et al., 2021), often within the OER context. This development suggests that OER are increasingly examined through the lens of good teaching.

In Atenas et al. (2024), we gave an overview of the global evolution of OER and observed that OER are first and foremost defined as educational resources that are legally available for reuse, modification, and redistribution. We commented that if OER providers equate “open” merely with “free of charge,” they overlook essential elements such as collaborative knowledge creation and a culture that embraces sharing.

Numerous contributions concentrate on specific topics, like Sousa et al. (2023) on the legal and technical openness of OER; yet, across the surveyed papers, the core OER arguments consistently emphasize free, legal access and the ability to reuse and adapt materials, which translate into costsaving publicfund returns, higher quality through community peerreview, and the broader inclusion of diverse learners. Our experiences within Unite! indicate that these popular OER advantages (e.g., cost efficiency and enhanced teaching practices) often dominate institutional narratives.

Given recent developments, particularly the urgency of climate change and shifting global political dynamics, sustainability and digital sovereignty have emerged as crucial considerations for OER. Moreover, international collaboration repeatedly underscores a fundamental but often underemphasized point: conventional copyright law does not provide a legal framework for the reuse, adaptation, and redistribution of educational materials.

European Union (EU) copyright law, implemented through separate national statutes in each member state, with only limited harmonization via the EU Copyright Directive, makes it extremely difficult to achieve legally sound, crossborder collaborative use of proprietary educational materials. This difficulty stems not only from the complexity of the rules themselves but also from a widespread lack of awareness of national copyright regimes and the differing regimes that apply in partner countries.

Therefore, we believe that three specific aspects deserve more attention, particularly in the context of European university alliances. Accordingly, we formulated the following research question: How do OER contribute to legal certainty, sustainability, and digital sovereignty in the context of European university alliances?

To address this question, we draw on arguments derived from our work, publications, and practical experiences in European OER projects. By sharing insights from the “Unite! OER Courses” project and related initiatives, we aim to provide a nuanced perspective on the strategic importance of OER for European university alliances.

3 Legal Certainty in Cross-Border Collaboration and Education

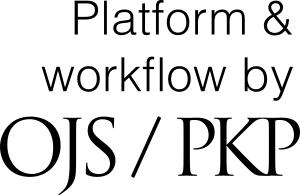

OER provide a legally secure framework for using educational materials across national borders, which is essential to fostering collaboration within European university alliances. At the core of this legal security, open licenses define the terms of use, adaptation, and redistribution of educational content. The most used Creative Commons (CC) licenses in the context of OER are CC BY (Attribution), CC BY-SA (Attribution-ShareAlike), and CC0 (Public Domain Dedication).

Figure 1: Icons representing and referring to the three CC open licenses (left) and a screenshot of a concrete license, namely, a contract for CC BY 4.0 International. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on materials from https://creativecommons.org/ (February 5, 2025)

CC BY (Attribution) allows others to distribute, remix, adapt, and build on the material, even for commercial purposes, if appropriate credit is given to the original creator. This attribution can include the project’s name, funding number, institutions, or specific individuals, making it possible to track and acknowledge contributions across projects.

CC BY-SA (Attribution-ShareAlike) includes the same requirements as CC BY but adds the condition that any derivative works must be licensed under the same terms. This ensures that adaptations remain open and supports the continued sharing and development of resources while preventing exclusive commercial exploitation. While CC BY-SA permits commercial use, it discourages intensive monetization given that any derivative must also be openly licensed.

CC0 (Public Domain Dedication) allows creators to waive all rights and place their work in the public domain, enabling unrestricted use without the need for attribution. This license is often used when the primary goal is maximum dissemination without legal constraints. For European universities, CC0 is particularly useful because, unlike in the United States, works cannot be voluntarily placed in the public domain. In the EU, works become public domain only after the copyright expires, typically 70 years after the author’s death. CC0 helps overcome this limitation by acting as a universal waiver where legal systems allow.

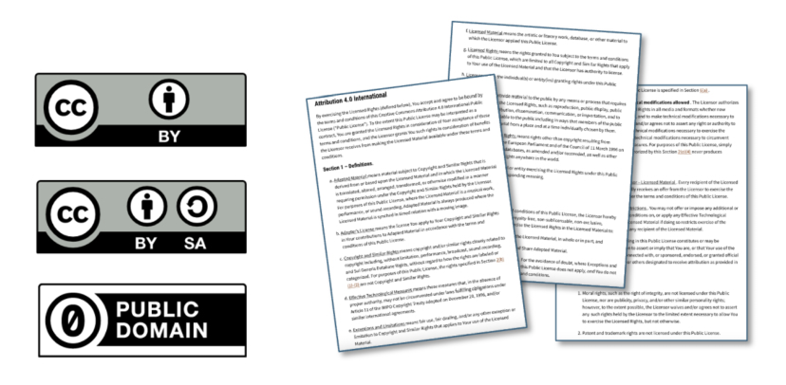

Figure 2: Lifecycle of educational resources and potential copyright infringements by authors and users. Source: Own figure

However, when open licenses are not used, significant copyright issues can arise, particularly in international academic collaborations and teaching in European university alliances (see Fig. 2). This concerns the production, revision, publication, distribution, and usage of the resources. It is often unclear which copyright laws apply, namely, the jurisdiction of the author(s), the user(s), or, in the case of Unite!, the country hosting the federated learning management Metacampus (see Ebner et al., 2024). This legal ambiguity is especially problematic when there are differences in copyright regulations, notably in the rules governing educational use at universities. Even within the EU, discrepancies exist regarding citation practices, the use of textbooks for teaching and learning, and other educational materials. As a result, reusing materials in new collaborations requires detailed agreements to define usage rights clearly. Without these agreements, it is generally assumed – at least in the European context – that only the original authors can reuse, modify, or adapt the materials. This legal uncertainty means that after a project concludes, adaptations, updates, or translations may no longer be legally permissible, which severely limits the long-term value and impact of educational resources (Schön et al., 2025).

The use of open licenses simplifies these complexities by clarifying the future use of jointly created resources from the outset. This reduces the need for extensive negotiations about usage rights during contract discussions or proposal writing, thus streamlining administrative processes in international projects. Moreover, while open licenses define usage rights, the original creators retain their copyright. This means that they can continue to use their materials in other contexts, even outside the open licensing framework. This flexibility is particularly important in academic environments where content may serve multiple purposes.

Our experience within the Unite! alliance shows that choosing an open license such as CC BY or CC BY-SA has often turned out to be much simpler for licensing the outcomes of collaborative international projects in the form of educational content - rather than having to negotiate the details of each partner’s copyright, usage, and exploitation rights. Future translations of the project results – and adaptations such as updates or content revisions – are therefore possible, including tailoring the material to the specific circumstances of each partner’s university. Additionally, for projects or partners concerned about the commercial exploitation of their results, CC BY-SA provides a balanced solution: although it permits commercial use, it mandates that any modifications or derivatives remain open, thus limiting the extent of commercial use. Through these mechanisms, OER not only address cross-border copyright challenges, but also foster a collaborative culture grounded in legal certainty and mutual respect for intellectual contributions.

4 OER and Sustainability in Educational Resource Development

OER promote sustainability by ensuring that investments in educational materials are reusable, adaptable, and not restricted by licensing limitations. This sustainability extends beyond environmental considerations to include economic, social, and educational dimensions, making OER a powerful tool for fostering long-term collaboration and reducing resource redundancy in academic institutions and alliances.

The concept of sustainability in education is closely linked to education for sustainable development (ESD), as defined by UNESCO (2017). ESD emphasizes the transformative role of education in addressing global challenges such as climate change, social inequality, and economic instability. OER support ESD by enabling the creation and dissemination of learning materials that are adaptable to diverse cultural and social contexts. This flexibility fosters critical thinking and promotes lifelong learning, supporting the development of competencies necessary for sustainable living.

The EU’s Green Deal and the European Education Area strategic framework further highlight the importance of integrating sustainability into education, calling for open, inclusive, and digitally resilient learning environments (European Commission, 2020). OER align with these goals by providing free and adaptable resources that reduce the economic and environmental costs associated with traditional educational materials.

The lifecycle of educational materials typically involves creation, use, adaptation, and eventual retirement. OER extend this lifecycle by enabling continuous reuse and modification, thus reducing the need to constantly redevelop new materials. This not only conserves financial and human resources but also supports the creation of high-quality educational content that evolves based on feedback and changing needs.

OER also align with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals). They facilitate inclusive and equitable access to education by removing cost barriers and enabling adaptation to diverse learning contexts. Furthermore, OER foster global partnerships by allowing institutions to share resources openly, enhancing collaboration and knowledge exchange across borders.

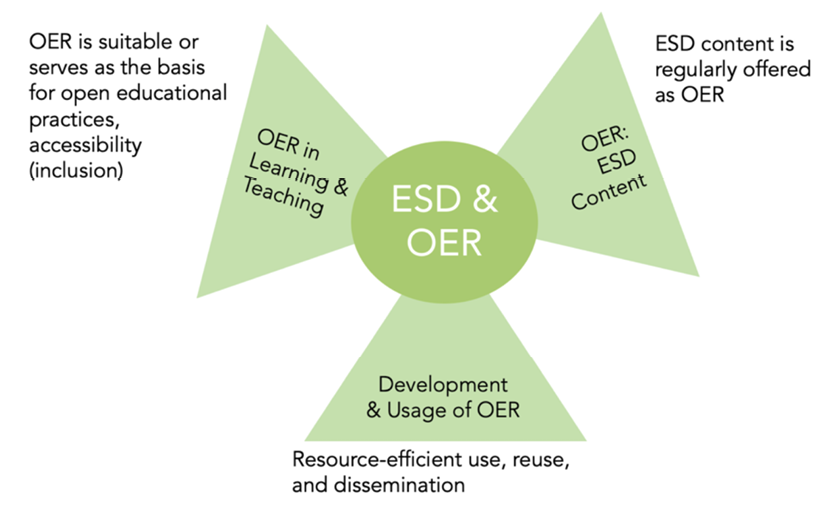

Figure 3: Three perspectives on ESD and OER. Source: Translation of Fig. 1 of Jakob et al. (2025)

OER contribute to ESD through three interconnected perspectives: (1) as content for ESD, (2) as a methodological approach to promoting ESD, and (3) as a catalyst for resource efficiency and accessibility (see Fig. 3; Jakob et al., 2025). These perspectives reflect how OER not only support the dissemination of sustainability-related knowledge but also foster educational practices and structures that align with the principles of ESD. The following overview is based on Jakob et al. (2025), a joint publication with the authors of this paper.

As content for ESD, OER enable the widespread sharing of sustainability-related content. Their adaptability allows for quick updates compared to traditional textbooks and supports the inclusion of diverse perspectives, such as indigenous knowledge and interdisciplinary approaches (McGreal, 2017). This flexibility ensures that educational materials remain relevant to current global challenges, such as climate change, social justice, and economic resilience.

As a methodological approach to promoting ESD, OER foster open educational practices consistent with ESD’s transformative learning goals. These include collaborative projects, peer learning, e-portfolios, and international knowledge exchange networks, which encourage critical thinking and active participation (Geser, 2007; Wiley & Hilton, 2018). Such practices empower learners to become change agents for sustainability in their communities.

As a catalyst for resource efficiency and accessibility, the initial creation of OER may require significant effort, but their reuse and adaptation are resource efficient, reducing the need for constant redevelopment (Schön et al., 2017). This efficiency contributes to the sustainability of educational systems, as evidenced during the COVID-19 pandemic when openly licensed materials facilitated rapid transitions to online learning (Kanwar & Daniel, 2020). Additionally, although OER are not inherently accessible, open licenses enable adaptations for learners with specific needs, such as translations into minority languages or formats for individuals with disabilities.

In conclusion, OER foster sustainability by maximizing the value of educational investments, fostering continuous improvement through reuse and adaptation, and promoting equity and collaboration in education on a global scale. By embedding OER in the broader framework of ESD and aligning with EU sustainability goals, educational institutions can play a pivotal role in driving transformative change.

5 Digital Sovereignty Through OER

OER strengthen digital sovereignty by reducing dependency on proprietary platforms and enabling institutions to maintain control over their educational content. In the context of higher education, digital sovereignty refers to the ability of institutions to independently manage their digital infrastructure, content, and data without relying on external commercial providers that may impose restrictions or create vendor lock-in scenarios.

The demand for digital sovereignty is increasingly emphasized in policy frameworks, particularly at the EU level. The European Commission has highlighted digital sovereignty as a strategic priority in documents like the European Digital Strategy (European Commission, 2020) and the Digital Education Action Plan 2021 – 2027 (see European Union, 2025). These initiatives stress the need for the EU to achieve greater autonomy in digital technologies, reduce its dependency on non-European tech giants, and ensure that its critical digital infrastructure and data are controlled within the EU. The rationale behind this focus includes concerns over data security, privacy, the resilience of digital infrastructures, and the protection of fundamental rights in the digital space.

One of the key risks associated with dependence on commercial platforms and proprietary software is the potential loss of control over educational data and content. This reliance can limit the flexibility of institutions to adapt resources to specific educational needs and may lead to long-term costs associated with licensing fees and platform dependencies. Moreover, proprietary systems often come with closed ecosystems that limit interoperability. This makes them difficult to integrate with other educational tools or share resources across institutions and borders.

OER provide a powerful alternative by allowing institutions to create, adapt, and distribute educational materials under open licenses, guaranteeing that content remains accessible and modifiable without external constraints. This autonomy is critical for universities, especially those involved in cross-border collaborations like Unite!, where diverse legal and technical environments require flexible, interoperable solutions.

Platforms such as iMooX.at, operated by TU Graz, exemplify how OER can enhance digital sovereignty. As an open massive open online course platform, iMooX.at hosts courses exclusively under CC licenses, thus maintaining educational content under the control of its creators and institutions. This approach not only supports the free flow of knowledge but also reduces the risks of vendor lock-in because the platform is built on open standards that promote interoperability and long-term sustainability.

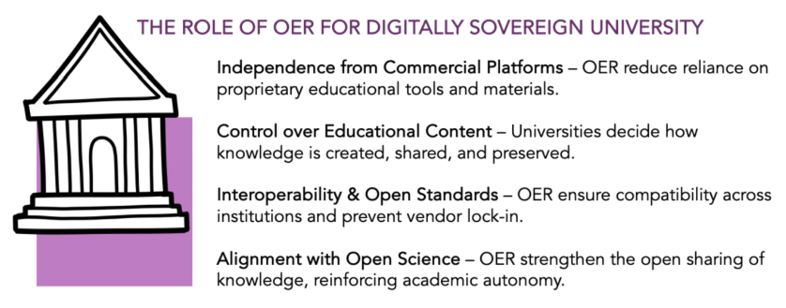

OER contribute to digital sovereignty by fostering an ecosystem where educational institutions are not merely consumers of commercial products but active participants in the creation and governance of their digital learning environments. In particular, OER enable universities to shape their own digital strategies, adhere to open science principles, and promote data privacy and security by minimizing exposure to third-party commercial entities. (Ebner & Schön, 2021). Fig. 4 provides an overview of the potential of OER for digitally sovereign universities.

Figure 4: Role of OER in digitally sovereign universities. Source: Own figure

Importantly, universities that do not actively engage with OER and open education face potential risks (see Ebner & Schön, 2021). These include the risk of losing their influence over the development of educational standards and practices. OER or free, accessible learning materials will be created and shaped by other actors, including private companies and lobby groups such as banks and firms (see Schön et al., 2017). As an evaluation of educational materials in Germany revealed, businesssponsored teaching resources tend to push commercial interests, bias information, and downplay criticism, often promoting products or portraying industries favorably (Bielke, 2014, p. 114). As a result, commercial interests may end up setting the norms, controlling narratives, and defining educational priorities, potentially distancing them from the principles of academic freedom, equity, and public interest. For smaller countries, the problem is even greater when OER are predominantly produced by external actors, in a form of imperialism. As highlighted in the Austrian National Education Report (2016), relying on OER developed in other countries can create a kind of dependency: if Austria does not want to fall into a colonial dependency in this new global market, national research efforts must be intensified both in developing sustainable business models and in establishing appropriate evaluation and quality assurance procedures for OER internet portals (Baumgartner et al., 2016, p. 116).

Moreover, universities have a fundamental responsibility to support OER and promote open education. As key stakeholders shaping society’s educational landscape, they play a critical role not only in knowledge creation but also in the training of future educators. Their involvement ensures that OER reflect pedagogical quality, academic rigor, inclusivity, and accessibility. By fostering open education, universities uphold their mission to serve the public good and promote lifelong learning, thus contributing to a more equitable and informed society.

In conclusion, OER empower educators and institutions to maintain control over their educational content, foster innovation through open collaboration, and support the development of resilient, independent digital infrastructures. This autonomy is essential for safeguarding academic freedom and promoting open knowledge exchange, and it contributes to the long-term sustainability of educational resources in the digital age – objectives that closely match the EU’s strategic goals for digital sovereignty.

6 Discussion

The analysis of legal certainty, sustainability, and digital sovereignty reveals that these interconnected themes collectively enhance the strategic role of OER within European university alliances. While each dimension offers distinct advantages, their combined impact strengthens the capacity of alliances like Unite! to foster cross-border collaboration, promote resilient educational ecosystems, and align with broader European policy objectives.

The legal certainty afforded by OER through clear licensing frameworks such as CC BY, CC BY-SA, and CC0 ensures that educational materials can be used, adapted, and shared across national borders without the risks associated with legal ambiguity. This not only facilitates international collaboration but also reduces administrative burdens related to copyright negotiations in projects and partnerships.

Further, sustainability underscores the long-term value of OER, in terms of both educational resource management and alignment with the SDGs. By enabling the continuous reuse and adaptation of materials, OER reduce redundancy, optimize resource allocation, and support institutional strategies aimed at sustainable development. This is particularly relevant in the context of university alliances, where shared resources are essential for fostering durable cooperation.

Digital sovereignty, a growing priority in European policy discourse, highlights the role of OER in reducing dependency on proprietary platforms and commercial providers. OER empower institutions to maintain control over their digital content and infrastructure, in keeping with the EU’s strategic objectives of digital autonomy, data security, and technological resilience.

Together, these three aspects position OER as more than just tools for cost reduction or pedagogical innovation: they represent strategic assets that support the core values and goals of European university alliances. Recognizing their potential can lead to more informed policy-making and strategic planning, ensuring that OER are integrated not merely as educational resources but as fundamental components of institutional development and international cooperation.

However, some limitations of this analysis must be acknowledged. The arguments presented here are based on specific projects and experiences, particularly within the Unite! alliance and related initiatives at TU Graz, and in line with EU and UNESCO papers. Although these insights offer valuable perspectives, they are not derived from comprehensive systematic literature reviews or meta-analyses. Future research could therefore expand on these findings by exploring a broader range of cases and conducting comparative studies of different university alliances and national contexts.

7 Conclusion

Given the strategic importance of OER in enhancing legal certainty, sustainability, and digital sovereignty, European university alliances are encouraged to integrate OER more systematically into their collaboration frameworks. This integration should go beyond individual projects and become a fundamental part of alliance-wide strategies. OER should be recognized not only as cost-saving tools but also as essential instruments for fostering cross-border cooperation, promoting educational resilience, and supporting the autonomy of institutions within the European Higher Education Area.

Policymakers and institutional leaders within university alliances should prioritize the development of comprehensive OER strategies. These could include the establishment of shared OER repositories, cross-institutional training programs for educators, and policies that incentivize the creation and reuse of OER. Embedding OER in the strategic goals of alliances can enhance academic collaboration as well as contribute to the EU’s broader objectives concerning digital transformation, sustainability, and educational equity.

In the “Unite! OER Course” seed fund project, we started from the assumption that engagement with OER serves as an excellent entry point into open science, which was confirmed throughout the project. The principles and practices of OER coincide with open science values, fostering a culture of openness, transparency, and collaboration that extends beyond educational materials to research practices (Mendez et al., 2020). This connection strengthens the overall development of open science within institutions and alliances, enhancing their competitiveness in EU funding calls, where open science has become an increasingly important evaluation criterion. By promoting OER, university alliances can thus simultaneously advance their open science agendas and improve their positioning in European research and education funding landscapes.

Several areas warrant further research. Comparative studies of different European university alliances could provide deeper insights into how OER are implemented in various contexts and which factors influence their success. Additionally, in-depth legal analyses of the implications of copyright laws in different countries, particularly for cross-border educational activities, could help address persistent legal uncertainties. Research on the impact of OER on digital sovereignty, especially in relation to data security and institutional autonomy, would also contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the strategic value of OER in higher education. By advancing research in these areas and strengthening the role of OER in strategic planning, European university alliances can better position themselves to meet the challenges of the digital age while fostering inclusive, sustainable, and autonomous educational environments.

Lastly, although this contribution focused on legal certainty, sustainability, and digital sovereignty, OER’s additional benefits should be noted. Notably, OER can enhance the impact and reputation of universities and alliances by increasing visibility and fostering recognition. OER ensure that the valuable work of educators and researchers does not remain hidden or face legal issues but can instead be shared openly and effectively across borders, university systems, and platforms. In the end, sharing is not just caring; it is strategic.

References

Ahlf, M., McNeil, S., & Nguyen, P. (2024). Open educational resources: Time, resources and sustainability in an ephemeral digital world. In D. R. Cole, M. M. Rafe, & G. Y. A. Yang-Heim (Eds.), Educational research and the question(s) of time (pp. 345 – 369). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-3418-4_19

Atenas, J., Ebner, M., Ehlers, U.-D., Nascimbeni, F., & Schön, S. (2024). An introduction to open educational resources and their implementation in higher education worldwide. Weizenbaum Journal of the Digital Society, 4(4), w4.4.3. https://doi.org/10.34669/wi.wjds/4.4.3

Baumgartner, P., Brandhofer, G., Ebner, M., Gradinger, P., & Korte, M. (2016). Medienkompetenz fördern – Lehren und Lernen im digitalen Zeitalter. In M. Bruneforth, F. Eder, K. Krainer, C. Schreiner, A. Seel, & C. Spiel (Eds.), Nationaler Bildungsbericht Österreich 2015, Band 2: Fokussierte Analysen bildungspolitischer Schwerpunktthemen (pp. 95 – 132). Leykam. https://doi.org/10.17888/nbb2015-2-3

Bellinger, F., & Mayrberger, K. (2019). Systematic literature review zu Open Educational Practices (OEP) in der Hochschule im europäischen Forschungskontext. MedienPädagogik: Zeitschrift für Theorie und Praxis der Medienbildung, 34(Research and OER), 19 – 46. https://doi.org/10.21240/mpaed/34/2019.02.18.X

Bielke, T. (2014). Qualitätskriterien für Bildungsmedien. In Lehrmaterialien aus der Wirtschaft. Praxisplus für den naturwissenschaftlich-technischen Unterricht (pp. 108 – 115). Industrie- und Handelskammer Darmstadt & Deutscher Industrie- und Handelskammertag e. V. http://www.bsohessen.de/blob/da_beruf/produktmarken/informationen/3451828/fa82635bd687ed0ae370c779c606f96b/Lehrmaterialien-aus-der-Wirtschaft-data.pdf

Butcher, N. (2011). A basic guide to open educational resources (OER). Commonwealth of Learning & UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000215804

Council of the European Union. (2021). European Universities initiative: Council conclusions pave the way for new dimension in European higher education. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2021/05/17/european-universities-initiative-council-conclusions-pave-the-way-for-new-dimension-in-european-higher-education/

Ebner, M., Kopp, M., Freisleben-Deutscher, C., Gröblinger, O., Rieck, K., Schön, S., Seitz, P., Seissl, M., Ofner, S., Zimmermann, C., & Zwiauer, C. (2016). Recommendations for OER integration in Austrian higher education. Proceedings of the Online, Open and Flexible Higher Education Conference, 2016, 34 – 44.

Ebner, M., & Schön, S. (2021, November). Digitale Souveränität durch offene Bildung und OER: Chance und Verantwortung der Hochschulen [Keynote]. Campus Innovation 2024, Hamburg, Germany. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356413139_Digitale_Souveranitat_durch_offene_Bildung_und_OER_Chance_und_Verantwortung_der_Hochschulen#fullTextFileContent

Ebner, M., Schön, S., Alcober, J., Bertonasco, R., Bonani, F., Cruz, L., Espadas, C., Filgueira Xavier, V., Franco, M., Gasplmayr, K., Giralt, J., Hoppe, C., Koschutnig-Ebner, M., Langevin, E., Laurent, R., Leitner, P., Martikainen, J., Matias, J., Muchitsch, M., ... Würz, A. (2024, January 31). Aligning IT infrastructures for digital learning amongst the European University alliance Unite! – The Unite! digital campus framework and requirements. Unite! Community 2 Digital Campus, Graz University of Technology. https://doi.org/10.3217/36yen-0wy21

European Commission. (2013). Opening up education: Innovative teaching and learning for all through new technologies and open educational resources. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52013DC0654

European Commission. (2020). European Green Deal. https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en

European Commission. (2025). Digital Education Action Plan: policy background. https://education.ec.europa.eu/focus-topics/digital-education/plan

Geser, G. (Ed.). (2007). Open educational practices and resources: OLCOS roadmap 2012. Salzburg Research. http://www.olcos.org/cms/upload/docs/olcos_roadmap.pdf

Hilton, J., Larsen, R., Wiley, D., & Fischer, L. (2019). Substituting open educational resources for commercial curriculum materials: Effects on student mathematics achievement in elementary schools. Research in Mathematics Education, 21, 60 – 76.

Hylen, J. (2006). Findings from an OECD study – Background note 2: Why are individuals and institutions using and producing OER? UNESCO. http://www.unesco.org/iiep/virtualuniversity/forumsfiche.php7queryforumspages_id=27

Jakob, J., Schön, S., Ebner, M., Gabriel, S., Liebhart-Gundacker, M., & Ruffeis, D. (2025). Offene Bildungsressourcen (OER) und Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung (BNE) an österreichischen Hochschulen. In W. Leal Filho (Ed.), Innovative Ansätze für die Nachhaltigkeitslehre und Forschung in der Hochschulbildung. Springer Spektrum.

Kanwar, A., & Daniel, J. (2020). Report to Commonwealth education ministers: From response to resilience. Commonwealth of Learning. http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/3592

McGreal, R. (2017). Special report on the role of open educational resources in supporting the Sustainable Development Goal 4: Quality education challenges and opportunities. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(7), 292 – 305. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i7.3541

Mendez, E., Lawrence, R., McCallum, C., & Moar, E. (2020). Progress on open science: Towards a shared research knowledge system: Final report of the open science policy platform. European Commission Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/00139

Mora, M. (2008). Open educational resources: Motivations, governance, and content protection [Master’s thesis, Carleton University].

Otto, D., Schröder, N., Diekmann, D., & Sander, P. (2021). Offen gemacht: Der Stand der internationalen evidenzbasierten Forschung zu Open Educational Resources (OER). Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 24, 1061 – 1085. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-021-01043-2

Schön, S., Kreissl, K., Dobusch, L., & Ebner, M. (2017). Mögliche Wege zum Schulbuch als Open Educational Resources (OER): Eine Machbarkeitsstudie zu OER-Schulbüchern in Österreich. Salzburg Research. http://l3t.eu/oer/images/band15.pdf

Schön, S., Ebner, M., Berger, E., Brandhofer, G., Edelsbrunner, S., Gröblinger, O., Hackl, C., Jadin, T., Kopp, M., Neuböck, K., Proinger, J., Schmölz, A., & Steinbacher, H.-P. (2023). Development of an Austrian OER certification for higher education institutions and their employees. In D. Otto, G. Scharnberg, M. Kerres, & O. Zawacki-Richter (Eds.), Distributed learning ecosystems (pp. 161 – 182). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-38703-7_9

Schön, S., Ebner, M., Hohla-Sejkora, K., Keller, E., Rapp, A., Ribeiro, M. H., Segradin, R., & Vicente-Sáez, R. (2025). A multilingual OER MOOC: A case study on production and usage in a university cooperation. Journal of Open, Distance, and Digital Education, 2(1), 1 – 16. https://doi.org/10.25619/y956n017

Sousa, L., Pedro, L., & Santos, C. (2023). A systematic review of systematic reviews on open educational resources: An analysis of the legal and technical openness. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 24(3), 18 – 33. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v24i3.7196

Technische Universität Graz. (2020). Richtlinie zu offenen Bildungsressourcen an der Technischen Universität Graz (OER-Policy). https://www.tugraz.at/fileadmin/user_upload/tugrazExternal/02bfe6da-df31-4c20-9e9f-819251ecfd4b/2020_2021/Stk_5/RL_OER_Policy_24112020.pdf

Tlili, A., Burgos, D., Huang, R., Mishra, S., Sharma, R. C., & Bozkurt, A. (2021). An analysis of peer-reviewed publications on open educational practices (OEP) from 2007 to 2020: A bibliometric mapping analysis. Sustainability, 13, Article 10798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910798

UNESCO. (2017). Education for sustainable development goals: Learning objectives. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444

UNESCO. (2019). Recommendation on open educational resources (OER). United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000370936

UNESCO. (2019). Recommendation on open educational resources (OER). United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000370936

UNESCO. (2017). Education for sustainable development goals: Learning objectives. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444

Unite! (2025). University Network for Innovation, Technology and Engineering. https://www.unite-university.eu/

Vicente-Sáez, R., Schön, S., & Ebner, M. (2024). Unite! University Alliance’s OER project Unite! OER courses – An open education initiative to develop open science competencies within Unite! (10/2023 – 09/2024) [Presentation, March 13, 2024, Aalto RDM & Open Science Training series]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10812652; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tbnNUYbccpw

Wiley, D., & Hilton, J. L. (2018). Defining OER-enabled pedagogy. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(4), 133 – 147. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i4.3601

Date received: 14 February 2025

Date accepted: 4 September 2025

Metrics

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Sandra Schön, Ebner Martin (Author)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.