Digital Volunteers during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Care Work on Social Media for Socio-technical Resilience

1 Introduction

Resembling previous crises, the COVID-19 pandemic has amplified volunteering actions by individuals in both physical and virtual spaces (Reuter et al., 2013). Depending on the disruptive context, people have performed various tasks to help others, ranging from carrying sandbags to protect against floods and organizing relief activities to providing online support (Purohit et al., 2014; Reuter et al., 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic has seen physical distancing used as a mitigation measure, accelerating digitization of both collaboration and cooperation (Horgan et al., 2020; von Humboldt Institute for Internet & Society, 2020). This prompts the assumption that social-media-based crisis volunteering has also increased (Lachance, 2020).

This plays out anecdotally: Across the globe, various initiatives have emerged online to provide digital volunteering in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Deutsche Welle, 2020c; Wired, 2020). This is reflected by German Facebook groups and Reddit threads, where users interact to share helpful information or express their need for support. Crisis informatics – which concerns computer-supported collaboration in disruptive contexts (Pipek et al., 2014) – has identified the use of social media in such situations as crucial for coping and sensemaking (Huang et al., 2015). Beyond the possibility of accessing information quickly in time-critical situations, individual users seek and offer (emotional) support, which complements more formal arrangements of crisis management (Huang et al., 2015; Reuter et al., 2018). As recognized by existing research (Harmon et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2012), most people are community-oriented, want to participate in relationships of care, and are committed to and seek voluntary work. This has been found to be important not only in general but also with regard to strengthening socio-technical resilience (Piccolo et al., 2018).

Understood as the capacity to cope with, respond to, and transform situations of crisis, resilience is not an individual responsibility but is determined by sociopolitical and technical conditions and applied to communities and their collective adaptability (Amir, 2018; Soden et al., 2014; Taylor et al., 2012). The socio-technical nature of resilience has been noted in more recent works emphasizing the co-constitution of productive social relationships and usable technologies (Amir, 2018). Crisis informatics is also committed to socio-technical resilience via its focus on successful computer-supported cooperation and collaboration (Pipek et al., 2014; Reuter et al., 2013).

However, although works on resilient information systems have referred to design requirements, such as robustness and flexibility (Heeks & Ospina, 2018; Müller et al., 2013), our work focuses on the extent to which successful collaboration can be achieved by using social media for crisis volunteering. More concretely, we consider the purpose of pairing needs for and offers of help and assess the productive nature of interactions from the perspective of feminist ethics of care (Bennett & Rosner, 2019; Helms & Fernaeus, 2021).

Following works of crisis informatics (Pipek et al., 2012; Thebault-Spieker et al., 2016), we analyze relevant Facebook groups and Reddit threads to capture the social media usage of individual users in disruptive contexts. We adopt a more critical stance towards crisis volunteering by characterizing it as unpaid care work, a relevant component of the process of overcoming crises (Soden & Palen, 2018). Related interactions can be understood as relationships of care and empathy that are mediated by social media platforms (Key et al., 2021; Kou et al., 2019). Building on insights into care and care ethics (Key et al., 2021), we invest in understanding informal crisis management as voluntarily caring for others, which may also include non-straightforward interactions as well as the reproduction of power relations (Helms & Fernaeus, 2021). Meanwhile, in a contribution to debates around the socio-technical resilience of communities in crisis (Soden & Palen, 2018), we formulate considerations that may be generative and legitimize interventions by design coming from feminist ethics of care.

Our work is threefold: We review the literature on computer-supported crisis volunteering and care work (see Section 2). Using our methodological approach (see Section 3), we analyze volunteering activities and interactions, taking into account relationships of care and empathy (see Section 4). We then reflect on potentials of technological interventions inspired by feminist ethics of care in the context of digital volunteerism (see Section 5 and Section 6).

2 Related Work

As we look at interactions on social media that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, we consider the focus of crisis informatics on digital volunteering in disruptive situations (see Section 2.1). Furthermore, our work builds on Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) research concerning care and feminist ethics of care (see Section 2.2) to capture both the potentials and the limitations of digital volunteering for strengthening socio-technical resilience.

2.1 Crisis Volunteering and Socio-technical Resilience

Crisis informatics concerns the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in disruptive situations, including different types of crises, from earthquakes to mass shootings (Palen et al., 2020). Paying special attention to public health crises, researchers have studied ICT usage during the spread of the Zika and Ebola virus (Gui et al., 2018; Tambo et al., 2017). By focusing on the COVID-19 pandemic, our study links to extant research on long-term disruptive and less clearly bounded events. However, emotional processes of coping and sensemaking have been found to generally catalyze crisis-related social media interactions (Huang et al., 2015) and apply to disruptive situations independent of the crisis type.

Other researchers have specifically concentrated on collaboration and cooperation efforts between formal and informal actors, ranging from emergency response teams to individual social media users aiming to instigate collective action (Auferbauer & Tellioğlu, 2019; Pipek et al., 2012; Reuter et al., 2019). In the context of crisis management, users have primarily been perceived as citizens (in relation to authorities), with societal hierarchies sometimes disregarded. More recently, the lack of focus on “bottom-up” dynamics contributing to socio-technical resilience has been noted (Piccolo et al., 2018, p. 24), and critical perspectives have highlighted the importance of considering social relations of power (Soden & Palen, 2018).

Following Karusala et al. (2021), we emphasize the importance of gaining insight into cooperative care work that is unpaid and embedded in societal structures. This may include not only computer-supported care work taking place on social media but also physical activities that depend on successful “articulation work” (Schmidt & Bannon, 1992, p.12), which refers to managing or trying to match offers of help and needs for help (Purohit et al., 2014). This includes the deletion of posts that are perceived as inappropriate (Yu et al., 2020). Studying both physical and digital volunteerism in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic by analyzing semi-public social media data allows for increased visibility and better insights into empathy and care as mechanisms for coping with crisis (Vyas, 2019). Meanwhile, as noted by Harmon et al. (2017), voluntary work is intrinsically motivated by care work’s capacity to create a sense of community and contribute to it. Elsewhere, Taylor et al. (2012) have recognized the importance of psychological support via social media for boosting community resilience.

2.2 Care Work and Feminist Ethics of Care

Recent works (Karusala et al., 2021) that investigate computer-supported cooperative work have emphasized the relevance of care and care ethics. Similar to other scholars, we adopt Tronto’s and Fisher’s (1993) definition of care as “everything that we do to maintain, continue, and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible.” (Helms & Fernaeus, 2021, p. 790) Following feminist HCI, contributions concerning care and care ethics have focused on the reciprocity of relationships alongside questions of vulnerabilities and responsiveness (Key et al., 2021). Building on these contributions, we perceive crisis volunteering on social media in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic as care work that is unpaid and conducted voluntarily.

As previous scholars have indicated (Karusala et al., 2021; Key et al., 2021), care has often taken place without notice or valuation. For example, Toombs et al. (2018) have noted that informal care work has often been neglected. In this context, the feminization of (unpaid) care work has also been recognized (Balka & Wagner, 2020; Williams, 2000). In looking at volunteering activities on both Facebook groups and Reddit threads, we are interested in how care work and empathy are performed. Considering HCI research that emphasizes social structures as explanatory factors for social media behavior (Schlesinger et al., 2017), the subject positions of individual users may contribute to the conduct of online care work. Accordingly, we assume “cumulative efforts of attentiveness and resilience” (Key et al., 2021) that are performed by user communities and enabled by social media platforms as relatively open spaces offering almost endless possible encounters. This means that care work may be distributed between group members and require less patience and waiting (Key et al., 2021) by single individuals than happens in more fixed, analog constellations.

Furthermore, assuming instances of crisis volunteering to be acts of goodwill, scholars have urged against romanticizing care (Murphy, 2015). Generally associating positive feelings with care is misleading: This can ignore relevant acts of care that seem less affirmative at first glance, and there can also be harmful unintended consequences, such as infantilization (Key et al., 2021). Although relationships of care are characterized by reciprocity, this is never without costs, and care may even demonstrate contradictions (Helms & Fernaeus, 2021). In their autobiographical study, Helms and Fernaeus (2021) focus on moments of agony and “impurities of care.” They propose illustrative concepts such as “willful detours” or “unhappy departures” as part of caring for their loved ones. Our work not only considers tensions around care work associated with, for example, misdirected activities but also focuses on technologically mediated communicative interactions that may indicate ambivalences but still be “generative and desired” (Helms & Fernaeus, 2021).

Arguing for empathetic ethics of care, the inherently positive conceptualization of empathy must be adapted carefully. Empathy is also relational and differentiates between the “empathizer” and “the empathized” (Bennett & Rosner, 2019). In their work, Bennett and Rosner (2019) note that empathy has often been perceived by designers as “a useful corrective,” that allows for the inclusion of minoritized people. However, “the promise of empathy” cannot be upheld when empathy is conventionally understood as feeling or imagining being like someone else, a process that leaves authority with the observing, empathizing subject and renders needs a spectacle (Bennett & Rosner, 2019). Instead, it is imperative to argue for empathy as identifying with each other while being aware of wider power relations, thus stressing positions of particular (instead of generalized) selves and others (Held et al., 2006). This demands continual attunements and close attendance to experiences (Cheong et al., 2021), which enables the “training [of] the senses” (Amrute, 2019) toward noticing possibilities for mutual sensemaking instead of reification of differences (Bennett & Rosner, 2019; Despret, 2013). We are interested in whether such valuable dynamics of empathy can be noted in conversations on social media and take the myriad ways of caring into account. Thus, to consider resilience-building dynamics, we follow pre-identified aspects of empathetic relationships (Bennett & Rosner, 2019, p. 298 – 299), such as reciprocity, continual attunement in a not entirely positive environment, and not trying to imitate other biographies. Although we adapt to recent insights on empathy, it is relevant to note that traditional understandings also recognize its basic meaning of sensemaking (Thieme et al., 2014). This may be fundamental to crisis volunteering, which necessitates coping.

2.3 Research Gaps & Research Questions

Although scholars have investigated various contexts, including long-term epidemiological crises (Gui et al., 2018), and various crisis management actors (Auferbauer & Tellioğlu, 2019), few studies of crisis volunteering have understood it as unpaid care work (Cadesky et al., 2019) or considered societal hierarchies in their assessment of socio-technical resilience (1st gap). Thus, we derive relevant interactions in the context of care mediated by social media platforms and capture instances of care and empathy that may also appear contradictory. In doing so, we build on existing studies (Bennett & Rosner, 2019; Helms & Fernaeus, 2021; Key et al., 2021) in an effort to contribute to the articulation of a more holistic picture. Furthermore, previous studies have mainly focused on care work in terms of the myriad forms of everyday support for household and community members (Harmon et al., 2017; Tellioğlu et al., 2014) (2nd gap). We complement these studies by demonstrating that care work is primarily conducted not only in physical households or emergency rooms but also on social media and in the context of specific crises. Finally, discussing technological mediation of care work in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, we contribute to reflections on the potential of interventions by design, which has been identified as an issue that research has only recently started to focus on (Bennett & Rosner, 2019; Key et al., 2021) (3rd gap).

To address these research gaps, we study Facebook and Reddit data. Interpreting our findings with an interest in feminist ethics of care, we focus on the potentials and limits of empathy and care in terms of fostering socio-technical resilience when responding to the following research questions (RQs):

1) What type of help has been offered on social media platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic?

2) How do users interact with each other regarding care-related requests and concerns on social media?

3 Methodology

3.1 Case Selection

We focus on five public German Facebook groups with local audiences that can potentially be traced. These groups emerged in the context of the spread of COVID-19 and were founded to structure help in times of crisis. We investigate digital volunteering during the “first wave” of the pandemic, which refers to the time in 2020 when people were starting to cope with the crisis and the first “shutdown” measures were implemented in Germany. Facebook has been chosen because it is comparatively inclusive and used by people of different gender, ages, and social classes (Hootsuite, 2021). Furthermore, Facebook functions on a local level. We selected Facebook groups from four major German cities: Hamburg, Munich, Cologne, and Darmstadt (see Table 1). These cities are all located in highly urban areas and ranked as the top four cities on the German Smart City Index 2020 (Bitkom, 2020), indicating a relatively high level of digitization. The public character of the groups allowed access to their content. To include the dimension of purely digital volunteering in our analysis, we also captured 15 threads from Reddit that concerned the COVID-19 pandemic and were trending at the time of the study in the site’s biggest German community (the subreddit “r/de”), which featured about 250,000 members in March 2020. We also looked for threads posted in smaller communities that were either regional, COVID-specific, or help-orientated (see Table 1). We selected Reddit because it is characterized by anonymity, represents an open space for different subcultures (Amaya et al., 2019), and serves as a frame of reference for analyzing interactions within Facebook groups. We expected differences in openness compared to Facebook where people commonly use their real names or at least demonstrate a higher degree of identifiability. Although Reddit may also allow for intimate interactions, we assume that crisis volunteering that extends into physical spheres is conducted particularly well on Facebook, at least partly due to it clearly providing names of users.

3.2 Data Collection

For the analysis, we examined five Facebook groups (2,709 posts) with a total of 15,462 members engaged in volunteering related to supporting people (in)directly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, we manually collected 15 Reddit threads (191 posts) from “r/de” (and smaller German-language communities) that addressed the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany and associated neighborhood support (see Table 1) by using search terms such as “COVID,” or “Corona” and “Help.” All posts and threads from mid-March (earliest 11 March 2020) to mid-July (latest 18 July 2020) were captured via screenshot to also consider non-textual information. For automated labeling, we translated the images into text files with pytesseract (Version 0.3.7), a python wrapper for Google’s Tesseract-OCR Library.

Table 1: Overview of analyzed Facebook groups and subreddits. The latter comprise different numbers of threads and indicate interactions in the context of virtual volunteering. The Facebook groups were all public, with their intuitive names referencing the COVID-19 pandemic and the particular city.

|

Platform Name |

|

Facebook #Coronahilfe Hamburg |

|

Facebook #CoronaHilfe Gruppe |

|

Köln |

|

Facebook CoronaCare München #CoronaHilfe – Nachbarschaftshilfe |

|

Corona Hilfe Facebook Corona-Quarantäne Hilfsnetzwerk DA und DA-DI |

|

Facebook Corona Hilfe Darmstadt |

|

Reddit r/de (7), r/removalbot (1), r/CoronavirusDACH (1), r/berlin (1), |

|

r/SchoolSystemBroke (1), r/frankfurt (1), r/karlsruhe (1), |

|

r/wasletztepreis (1), r/einfachposten (1) |

3.3 Data Analysis

We conducted a content analysis. For qualitative evaluation, collected data were manually coded by an interdisciplinary research group skilled in computer science, HCI, and political science with the help of MAXQDA (Analytics Pro 2020). The interdisciplinary approach of consensus coding (Wilson et al., 2018) was especially helpful for working with social media as an interface between information technology and the social behavior of individuals. In addition to drawing on the empirical data collected, the coding scheme was developed by referring to previous HCI research into care relations, feminist ethics of care, and social media behavior. The collected screenshots of the Facebook groups and Reddit were coded in two runs based on iteratively created code categories and (sub-)codes (see Appendix, Table 4). The first run was conducted by one researcher and the second run by the other three researchers, producing a total of 38,613 codes (examples appear in Table 5 of the Appendix). We also quantified some results, including auto-code relations. Although manual coding helped to explore the data and structure the qualitative analysis, automated labeling was employed to capture patterns – including co-occurrences – of system features (e.g., links or likes) and words.

4 Findings

We present tasks conducted in the context of crisis volunteering in Germany during the “first wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic (RQ1) (see Section 4.1) and then examine these activities in terms of generative relationships of care and empathy and demonstrate how social media users interacted with each other in the context of crisis volunteering (RQ2) (see Section 4.2).

4.1 Taking Care: Volunteering Tasks during the COVID-19 Pandemic

The analyzed Facebook groups and Reddit threads represent important sites of support offering and seeking. These social media interactions indicate that crisis volunteering is needed, filling a gap and thereby contributing to crisis management by helping communities to “repair” themselves and get through the pandemic “as well as possible” (Tronto, 1993).

The different tasks (see Figure 1) are consistent with the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially considering related policy measures, such as mobility restrictions. As indicated in the group info, digital volunteering in the context of Facebook groups predominantly involves matching (physical) help demands and offers via digital connectivity:

This group shall help people in Darmstadt (...) who are in quarantine or in a high-risk group by taking out the trash, going grocery shopping, etc. (Darmstadt-I)

The most frequent offering activity was giving advice that covered many topics, including, for example, “where can I find yeast (due to a shortage, AN)” (Hamburg-193). Shopping relates to governance measures that aim to ensure physical distancing. Notably, users find it particularly important to offer help to vulnerable people at risk, as demonstrated by Darmstadt-I-35a: “I can go grocery shopping for people in quarantine.”

Figure 1: Volunteer tasks, including offers to help and requests for help from Facebook group members and Reddit users. The codes include both digital (e.g., information) and physical (e.g., shopping) volunteering. Note that volunteer tasks can fall into the category of both digital and physical help (e.g., IT support). “Volunteering” describes volunteering in general (i.e., no specification by the person offering it). “Food” and “Cooking” can be differentiated as follows: the former describes offers of food donations, whereas the latter represents cooking for another person.

The specific character of the COVID-19 crisis also shows in the provision of voluntary work such as educational assistance or childcare, prompted by the closure of schools and kindergartens (Munich-12). These special circumstances are also evident in the occurrence of more online-focused volunteering, such as proposing digital tools for entertainment:

I found an effective way to pass the time […] You only need a guitar. If you are in the mood for something like that, I can recommend an online guitar course. (Darmstadt-I-139)

Due to the obligation to wear mouth-nose protection in certain spaces in Germany, people sewed masks1 for not only other individuals but also institutions in need (Munich-275). Meanwhile, in addition to COVID-19-specific volunteer services, general crisis support was also offered, including donations and the dissemination of information. Although the selected Facebook groups also provide digital help in the form of information and mental support, they mostly

focus on physical volunteering. On Reddit – a predominantly anonymous platform that does not have as a principal purpose physical connection between users – volunteering focuses exclusively on virtual help in the form of, for example, mental support (Reddit-4). In some instances, users refer to analog places or domestic spaces as “going outside” (Reddit-1a). This suggests that volunteering on Reddit does relate to and influence the analog lives of users. However, there is considerably less discussion of domestic-work–related volunteering, contrasting with the variety of community-oriented activities managed simultaneously by Facebook groups.

Furthermore, “articulation work” (Schmidt & Bannon, 1992, p. 12) is conducted by group administrators by organizing interactions, which includes deleting regressive posts (Hamburg-45, Cologne-3) and restructuring threads according to city districts (Darmstadt-I). This is crucial for successfully matching needs and offers of care work. Combined with frequent articulations of needs, which produce opportunities for volunteering, organizing interactions enables the establishment of reciprocal relationships of care. However, singular offers of care work may sometimes be overlooked (Darmstadt-I-44, Hamburg-124) and devaluated, and identifiable users who ask for support may experience misdirected offers: “Maybe this is meant as a nice offer by [@username] but one could exploit the situation” (Cologne-3).

Across both Facebook and Reddit threads, users articulated offers of support (397 times) and requests for support (246 times), indicating an oversupply of help. While it is important to gain an overview of the different types of volunteering activities that were performed, it is also necessary to capture the quality of such care work. Building on feminist ethics of care, the following subsection investigates these care-related interactions with respect to their effectiveness in creating productive, empathetic relationships in times of crisis.

4.2 Effective or Failing? Potentials and Limitations of Volunteering via Social Media

Building on scholarship dedicated to care work, we focus on care as a social relationship between human subjects (see 4.2.1) that is carried by empathetic, reciprocal interactions (see 4.2.2). Given that researchers have also recognized the limitations of romanticizing care work as entirely positive, we investigate more serious instances that may appear less affirmative but still be effective alongside counter-productive interactions that also take place in the conduct of care work (see 4.2.3).

4.2.1 Relationships of Care: Embedded in Socio-technical Contexts

Observation of care-related user interactions on social media reveals both volunteers and social media users who articulated needs to be human subjects embedded in social structures. Subject positions are also translated into the sphere of social media, with people directing appeals to offer domestic labor specifically to women. However, social media groups also enable discussion of such problems and empower diverse people in need via autonomous self-ascription, which increased visibility.

Traditional understandings of the social division of labor are implied by expressions that solely address women by using the feminine 2 forms of nouns describing people as, for example, “seamstresses” (Näherinnen) (Munich-124) and “embroiderers” (Strickerinnen) (Hamburg-65) while utilizing the masculine and feminine forms (see Table 2) to refer to doctors or citizens (Reddit-3i, Darmstadt-I-115), with only a few moving past binary categories by using “*” (Hamburg-92), “¬_” (Cologne-1) or “:” (Munich-101) between the word stem and gendered suffixes or gender-neutral nouns for description. Addressing exclusively women in the context of seaming or knitting reflects a naturalized understanding of women’s roles, notably regarding activities that are primarily understood as unpaid domestic work or low-paid jobs pertaining to the tertiary sector. This leads related activities to be not only formulated as female but also devalued because required skills are perceived to be easily acquirable when apparently broadly prevalent. In some instances, awareness of this imbalance can be noted (Darmstadt-I-175b, Reddit-13c, Reddit-13d), with Reddit users recognizing that women are often employed part-time and acknowledging that “when you (additionally; AN) work in your free time as a neighborhood volunteer, you sure work more than 100 percent” (Reddit-13d). In this regard, the workload and lack of monetary compensation are discussed as a gender issue.

Meanwhile, people receiving care constitute an essential part of care relationships. User requests show that, intersecting with gender, money and health both represent important factors in the formulation of needs. This is reflected in user self-identification and external attributions according to class (see Table 2, frequencies of “Money” and “Ill”) or able-bodied status (Hamburg-208). Age and physical fitness were seen as main identifiers in the context of the public health crisis (Darmstadt-I-121a, Darmstadt-I-106a). One user requested help for an “older married couple, the wife is in a wheelchair[...] and they do not have internet, only telephone’ (Darmstadt-II-70). Notably, in the context of this request, the address of the couple, including the street name, was partly published. Hence, although the visibility of different subject identities crucially increases in times of crisis, it also becomes apparent that non-users of social media do not necessarily benefit from virtual volunteering.

Table 2: Overview of occurrences and co-occurrences of codes in the Facebook groups described in Section 4.2, including codes that relate to system features.

|

Code(s) Freq. |

Code(s) Freq. |

Code(s) Freq. |

|

Likes 2,652 |

Courtesy Form 203 |

Money 107 |

|

You 1,146 |

Likes + Thank 182 |

Binary 43 |

|

You |

|

|

|

Thank You + ! 1,037 |

Ill 165 |

Non-Binary 32 |

|

Thank You 786 |

Ill + Corona 113 |

Only Female 28 |

The digital gap is stressed by frequent references to being online and to technologies such technology such as PayPal (Munich-266) and by discussions regarding the quality of different messenger applications (Reddit-9a, Reddit-9c). Although users also mention analog communication formats, such as mail (Hamburg-138, Munich-293), Facebook groups constituted the main point of reference and frame of action (see Table 3).

In general, the data reveal an awareness that age, represented by reference to “old women” (Hamburg-46), and disability, exemplified by reference to a “blind woman” (Munich-248), may be factors associated with the need for support during the pandemic. At the same time, self-ascription in posts demonstrably increased the visibility of the marginalized voices of queer users (Hamburg-46), single mothers (Munich-460, Hamburg-83), and users with mental health issues (Reddit-2f, Reddit-2g). This may have encouraged empathy among particular users rather than relations based on abstract generalizations about broad groups of (minoritized) people.

Table 3: Overview of occurrences and co-occurrences of codes in the Facebook groups, including codes that relate to system features.

|

Code(s) Freq. |

Code(s) Freq. |

Code(s) Freq. |

|

Http + Likes 389 |

Http + Here 160 |

Message 57 |

|

Group 384 |

Hashtag 143 |

Internet 37 |

|

PM 304 |

Post 124 |

PayPal 20 |

|

Http 222 |

Phone Call 115 |

Digital 14 |

|

Write 192 |

Administrator 109 |

WhatsApp 11 |

|

Http + Link 182 |

Online 95 |

4.2.2 Articulating Feelings and Thanking Volunteers: Reciprocity in Relationships of Care

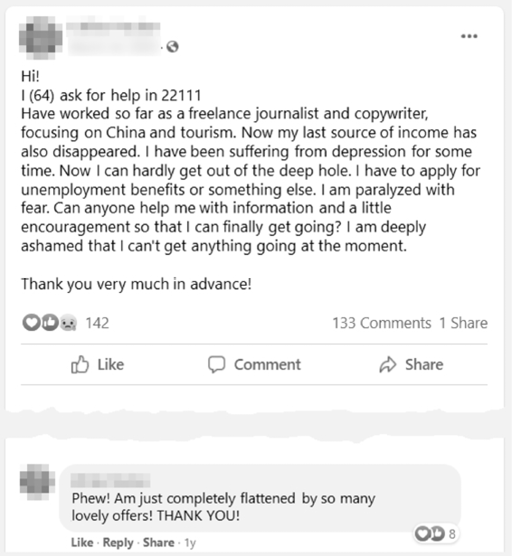

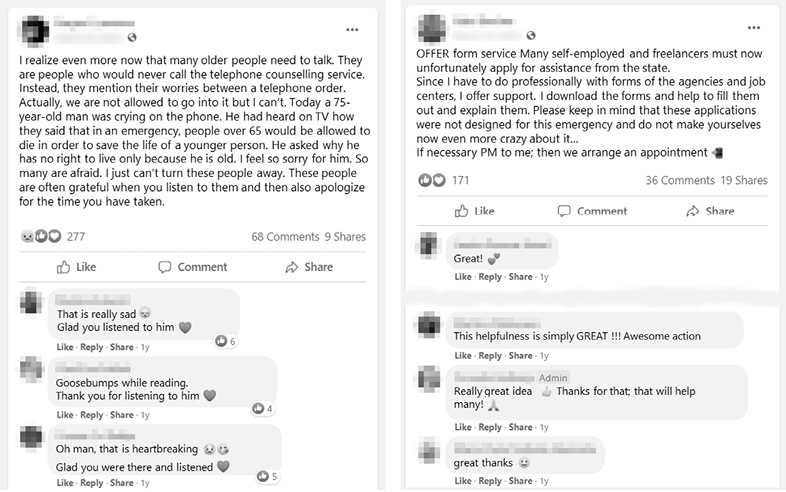

We identified 4,980 items representing emotional language, including posts and messages exposing feelings, concerns, and empathy. In several posts, people described their precarious pandemic situation (Hamburg-83), exposing their vulnerable positions. For many who had previously faced hardship, the situation had worsened (Hamburg-115). Numerous individuals reported depression and mood swings (Reddit-2b), and some people emphasized that they had never been in a similar situation before and felt uncomfortable (Hamburg-88). In response to such posts, many persons reacted empathetically and helpfully (Reddit-2e). Regarding risk groups and the overall situation, many users expressed their concerns and fears (Munich-418). For example, they showed sorrow about not being allowed to visit relatives in the care home (Darmstadt-I-110c). Furthermore, emotional language was identified in requests for support, expressions of gratitude (see Table 2, frequencies “Thanks”), and articulations of pandemic solidarity (Cologne-3). One user emphasized the importance of sticking together: “[N]ow our social cohesion is pretty important. Let us prove that we are one” (Darmstadt-I-106a). Numerous group members underwent coping processes, stressing that people should look out for each other and stay healthy (Munich-173). Social media users complimented and addressed other people directly, stating how great they were: “You are and remain a good soul with a very big heart “ (Darmstadt-I-88a); “You are angels” (Darmstadt-II-30).

Many members used smileys, hearts, or shamrocks to emphasize their feelings. They also “liked” posts (see Table 2, “Likes”) and responded with emoticons (see Figure 2), often in combination with capitalization and exclamation marks. Affirmative emoticons were mostly used in conjunction with thankfulness, compliments, and greetings (see Figure 3). Although affirmative statements helped to generate a productive atmosphere, it is possible that this also implied the hierarchization of group members and constituted a cost for users asking for support. That is, gratitude and affirmative reactions may function as a currency used in exchange for unpaid care work. This is indicated when considering instances, in which people did not immediately reflect proactiveness and positive reactions to help offers, which left users unsatisfied: “[Y]ou should try a little and not only ask for help” (Hamburg-97). This experience is also captured by a female user who is in agony and refuses to subordinate herself: “My kids are really demanding right now[...] No, I’m not [shameless]” (Hamburg-97). In response, other users infantilize her: “[@username] Just use your bike. Or scooter. Or go for a walk in quiet streets. Or do your children have to sit all day in a playpen?” (Hamburg-98).This suggests that when physical (i.e., more clearly defined) care work is organized, empathy is at times conditional, tied to the stereotypical images of people in need to which volunteers can relate (reflecting empathy as “feeling-like”). Nonetheless, although emotional and affirmative articulations may reinscribe problematic stereotypes, they also reflect the empathy and reciprocity that are foundational for care work.

Figure 2: User reacting to the unexpected high number of offers. Likes given by others enable affirmative feedback (own translation).

(a) Example of affirmative interactions (b) Example of affirmative interactions

(a) Example of affirmative interactions (b) Example of affirmative interactions

Figure 3: Emoticons and symbols emphasize sentiments in posts indicating appreciation and empathy (own translation).

4.2.3 Volunteering as Serious Business: Straightforward Problem-solving and Encountering Regressive Tendencies

Contrasting with positive, emotion-laden statements, we noticed that formal language was rarely employed, with only occasional users addressing others via the courtesy form (see Table 2) or thanking them very formally: “With all sincerity and all my respect (...)” (Hamburg-152). Both group membership and the context of the crisis may have encouraged the use of less formal language. Courtesy forms reflect interpersonal distance, which might inhibit relationships of empathy. The use of direct language – that is, clear statements or imperatives – was also observed. Again, this may be due to the character of the group, which enables quick chats. Direct language was typically used when referring to external institutions, including the legal system (Darmstadt-I-104a, 134a) and science (Darmstadt-I-142d). For example, users tried to convey bureaucratic information clearly:

[@username] According to the monthly update from the unemployment agency, anybody who has a child noted in their income tax card gets 67 % of their salary from their employer. (Hamburg-140)

Furthermore, users did not tend to use emotionally charged language when informing others about infection protection rules that were then novel: “If you are subject to quarantine by the health agency, you must not leave your home” (Darmstadt-I-120d). When referencing external institutions, such as employers or emergency services, users focused on providing information based on their personal knowledge clearly (Darmstadt-I-116b). Principally agnostic to user social backgrounds, system features such as hashtags were efficiently used to reference the respective local group or attend to the needs of particularly vulnerable persons (see Figure 4). Similarly, links were shared by users to address others in a straightforward manner (see Table 3). Furthermore, the standardized use of chat abbreviations indicates that system functions of Facebook groups that can be found across social media contribute to the efficient conduct of activities.

Figure 4: Example of typical use of hashtags, which refer to diverse issues such as, in this case, donations for homeless people (own translation).

Meanwhile, direct language was used when clarifying statements about misinformation, sometimes initially in an attempt to convince the other side: “As you are not able to offer any evidence, spare me the crap[...] [@username] Blocked” (Munich-31). The same was also true for passive-aggressive and angry statements. Direct language was also used by one moderator, who intervened in conversations (Darmstadt-I-121a, 121b). Ultimately, the use of direct language indicates that care work and empathy should not be romanticized. Seemingly less affirmative statements may contribute to the achievement of goals and empathy may be reflected by respectful, more formalized interactions that acknowledge aid receivers as autonomous individuals.

These observations also demonstrate that users may need to “depart” unhappily from regressive statements (Helms & Fernaeus, 2021). Curse words that primarily reproduced socio-psychological stigmata – such as labels like ‘dumb’ and ‘idiots’ (Hamburg-47) and references to human excrement (Reddit-2h, 2j) – prohibit the establishment of empathetic and productive relationships of care. Notably, curse words were frequently used to draw attention to people not respecting the rules related to the COVID-19 pandemic or believing in conspiracy myths (Reddit-9e). Related repetitive interruptions undermined the capacity of users to empathize with each other.

That is, direct pragmatic statements and regressive behavior both indicate that a superficial understanding of empathetic care work as wholly positive or altruistic does not hold up. While the conduct of care work by social media users relies heavily on affirmative interactions, it also includes less obviously affirmative and even counter-productive instances.

5 Discussion

Summarizing these findings (see Section 5.1), we consider how technological mediation by social media in the context of crisis volunteering contributes to the socio-technical resilience of communities and propose directions for intervention (see Section 5.2).

5.1 Care Work in Times of Crisis and the Ambivalence of Empathy

Our first interest here (RQ1) is the tasks conducted (see Section 4.1), with the findings demonstrating that both virtual and physical volunteering (Reuter et al., 2013) were important and Facebook was more appropriate for matching offer of and needs for analog help than Reddit, whether or not activities were crisis-specific (e.g., shopping for groceries). This may be due to Facebook’s local character, with the offer of informal channels for the exchange of advice between individuals impacted by crises distinguishing social media platforms such as Reddit.

Furthermore, volunteering tasks reflected typical care activities (e.g., buying groceries, education). Our understanding of digital volunteering as (unpaid) care work is supported, considering that interactions contribute to individuals getting through the pandemic “as well as possible” (Tronto, 1993) and complement official efforts at crisis management. However, misdirected offers also occurred, hinting at the unintended consequences of well-meant, empathetic interactions. Nonetheless, ultimately, interactions on social media allowed for “cumulative efforts of resilience and attentiveness” (Key et al., 2021, p. 2). On social media, continuous responsiveness is prevalent, with users requiring less patience and waiting on both sides (Key et al., 2021). This is represented by an oversupply of help offers.

The second part of the analysis (see Section 4.2) investigates how people interacted with each other in the context of crisis volunteering on social media (RQ2) and, thereby, the extent to which extent crisis volunteering on social media yields generative dynamics of care work and empathetic relationships. We first focused on the subjects involved, who correspond to sometimes hierarchical relationships of care and empathy (see Section 4.2.1). This enables us to see unpaid care work attributed to women, especially that related to traditional household tasks. This supports existing feminist critiques (Balka & Wagner, 2020; Williams, 2000) of the naturalization of care work as feminine and the concomitant devaluation of such work (Karusala et al., 2021). More recent work has already recognized the necessity of investigating HCI in the context of historical power relations and structural inequalities (Bødker et al., 2023; Erete et al., 2023). Because external gender attribution of social media users poses ethics problems (Fosch-Villaronga et al., 2021), our work is limited to offering broader evidence for the unequal distribution of labor based on gender roles. However, the relevance of subject positions can be illustrated by referring to self-ascribed identities. Identifiers of help receivers also reveal that able-bodied status and class contributed to the (re)production of different identities on social media (Bennett et al., 2020; Schlesinger et al., 2017). This may be due to the specific character of the COVID-19 pandemic as a public health crisis and enables insight into the subject positions of users and volunteering citizens (Schlesinger et al., 2017). Exposure of vulnerabilities by particularized users enhanced empathetic interactions (i.e., “feeling with” instead of “like” others; Bennett & Rosner, 2019, p. 298). Thus, the visibility of marginalized voices can be increased on social media, as further demonstrated by the use of gender-sensitive language in appeals to the two target groups (i.e., volunteers and support receivers).

Next, we build on reciprocity as an important feature of empathetic relationships of care (see Section 4.2.2) in the form of affirmative interactions, expressions of gratitude (Briton & Hall, 1995; Waterloo et al., 2018), and rewards for volunteers. Beyond immediate positive reactions to support-offering individuals, the articulation of feelings and interest in social interaction represent important processes of coping and sensemaking (Huang et al., 2015) in crisis via the offer of emotional and mental support (Taylor et al., 2012). However, empathy was at times conditional, depending on whether a user showed sufficient thankfulness or posted regressive, discouraging statements.

Finally, considering the seemingly less-affirmative side of interactions and the ‘unhappy departures’ (Helms & Fernaeus, 2021, p. 797), we find that volunteering is not always perfect and does not always engender satisfying results (see Section 4.2.3). This insight can be drawn based on queer feminist HCI scholarship, which has focused on tensions and contradictory dynamics that are “not ‘in-line’ with normative expectations of care as positive and fulfilling” (Helms & Fernaeus, 2021, p. 789). Furthermore, we illustrate the value of clear and straightforward communication on social media. This is supported by system features such as links, hashtags, and thread structuring, which offer the potential to organize interactions according to the underlying goal of matching help needs and offers. This exemplifies the effective care work that is essential to boosting socio-technical resilience and reflecting more symmetrical partnerships between individual social media users (Bennett & Rosner, 2019). Nonetheless, infantilization and regressive tendencies also come to light, with the data demonstrating that this hindered successful interactions (Helms & Fernaeus, 2021). Feminist ethics of care – following the claim of focusing on meeting existing and diverse needs via empathetic, equal, and reciprocal relationships – concern these valuable and sometimes ambiguous human interactions. Ultimately, the analysis reveals both the potential of care work conducted on social media to contribute to individuals coping with crises and the accompanying unproductive encounters. It can prove beneficial for both volunteers and people who request support to adjust interactions on social media to include marginalized voices and, thus, make informal crisis management more effective. However, as HCI scholarship has indicated (Bødker et al., 2023), technical solutions may be limited (or counter-productive) in terms of their effect on structural inequalities. In this manner, this work links to prior studies on crises and emphasizes the need for the conduct of systematic and critical analyses of (highly relevant) social media interactions during crises.

5.2 Social Media as a Space for Volunteering and Community: Boosting Socio-technical Resilience

Technological development is based on “continual acts of attunement” (Bennett & Rosner, 2019, p. 298) – that is, “training the senses” (Amrute, 2019, p. 59) – and may contribute to “affective partnership” that is aware of differences but does not reify them (Bennett & Rosner, 2019, p. 298). We identify points of intervention for crisis informatics dedicated to feminist ethics of care. Generally, it should be noted that Facebook groups feature less fixed hierarchies in the relationships between caring subjects and those who are cared for. This allows for “shared experiences” and the capacity “to recover empathy as a creative process of reciprocation” (Bennett & Rosner, 2019, p. 298). In the following, we consider social media as a frame of action with such potential for structuring crisis volunteering and derive implications for different levels of abstraction to boost socio-technical resilience. With the COVID-19 pandemic as our case study, we consider care work accumulated over a longer time span. However, informal, unpaid volunteering is also conducted in imminent disruptive situations and embedded within broader power relations (Karusala et al., 2021; Palen et al., 2020). This means that proposed HCI interventions aiming for more ethical and empathetic interactions may also be relevant to other scenarios, in which it is necessary to adapt and deal informally with crisis. Existing works from crisis informatics that focus on efficient matching solutions (Purohit et al., 2014) may also build on insights relating to the socio-technical production of specific needs and offers. Meanwhile, contexts of individualistic risk cultures (Reuter et al., 2019) demonstrate increased interest in successful informal volunteering. Thus, the following section details implications for HCI interventions for unpaid crisis volunteering on social media.

5.2.1 Support Bottom-up and Flexible Tools for Local Crisis Management.

In contrast to Reddit, Facebook is frequently used for local, in-person volunteering. Looking at activities conducted reveals that such care work fills a gap in COVID-19 crisis management by enabling the articulation of diverse requests for support and enabling users to cope (Huang et al., 2015). Offering advice as part of digital volunteering proves particularly relevant, and social media proves an appropriate space for such care work to be conducted efficiently. Furthermore, the results indicate that the various volunteering activities matched the specific context of the crisis and enabled the visibility of different needs and subject positions. Top-down approaches to crisis situations miss the opportunity for relatively free interaction steered by administrators and depend on standard and agnostic system features. Although related care work is unpaid and excludes people who are not consumers of social media sites, it is important to encourage bottom-up volunteering that reflects social context outside of formal volunteering (Harmon et al., 2017) and allows for empathetic interactions. Although the findings indicate that certain activities are central to crisis volunteering and offer thematic orientation for designing volunteering platforms, there should always be space for the articulation of specific needs by community members themselves.

5.2.2 Aim for a More Equal Distribution of Resources and Diverse User Involvement

Given that appeals to women to contribute to care work were made and (self-)descriptions of people in need demonstrated that intersectional issues (e.g., money and health) to be defining their social context, societal structures are apparently translated into the digital sphere (Schlesinger et al., 2017). Although questions of social justice – such as the legitimate distribution of unpaid care work – cannot be solved technologically, social media should at least not amplify differences in workload and needs depending on the societal positions of individuals. However, because we rely on insights from third-person accounts and self-ascriptions, future studies concerning crisis volunteering should (e.g., via interviews) explore reasonings behind (un-)engagement with care work on social media and whether it is tied to gendered understandings of it. Potentially, male users can be nudged to participate to balance unequal workloads. Considering local environments, the analysis indicates the necessity of implementing measures at the community level to support people in marginalized positions.

5.2.3 Strengthen Matching Efforts to Support Group Administrators

Successfully conducting care work on social media requires continuous attentiveness (Key et al., 2021). While both offers of and requests for support may easily be overlooked, detours are not automatically pointless, instead having potential generative power (Helms & Fernaeus, 2021). However, when caring ultimately cannot take place due to overload and the inability to match requests and offers, administrator actions can be supported by implementing “check symbols” or visualizing open requests. Although Reddit’s upvoting and downvoting system and “liking” posts on Facebook already indicate responsiveness, more emphasis on successful “articulation work” could also reflect the valuation of serious care work efforts, contrasting them with less willful encounters and enabling potentially more binding interactions (Schmidt & Bannon, 1992, p. 12).

5.2.4 Increase Awareness of Counter-Productive Tendencies

Finally, we have noted that although it may not be possible to circumvent the occurrence of some noisy or “naughty” interactions (Helms & Fernaeus, 2021, p. 798), there are instances that prohibit ethical care work and overemphasize regressive and negative dynamics of empathy. Reinforcing social differences by gendering care and using insulting language does not encompass empathy (Bennett & Rosner, 2019). Administrators of volunteering groups can be supported by social media providers to establish group rules or a code of conduct and to detect discrimination. Meanwhile, foregrounding the relevance of visibility and inclusive language encourages empathy as feeling with others (Bennett & Rosner, 2019).

6 Conclusion

As in the case of other crises, people formed local volunteer groups to coordinate help during the COVID-19 pandemic. This meant not only providing physical help but also interacting on social media and communicating using other digital technologies, which was facilitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, a context that foregrounded physical distancing and digital means of help. The sheer quantity of exchanges of affirmative phrases is notable and establishes the foundations for the conduct of empathetic care work. Meanwhile, we observe the conduct of various tasks, including typical (domestic) care work such as shopping, taking care of others, cooking, and sewing. However, users also performed more technical work and used direct language when they saw the need for clarification, indicating that care work offers more than just emotional support and affirmation. Although the latter is crucial to coping with crises, the problem-solving – oriented exchange of factual information also contributes to socio-technical resilience and reflects empathy as feeling with others (Bennett & Rosner, 2019) by enabling the uninterrupted articulation of the needs of (marginalized) individuals. Although the merit of flexible general-purpose groups is acknowledged and the devaluation of care work is a prominent social issue, ethically aligned technology may enhance both volunteering and elevate reciprocal care relations by improving matching functions. In this regard, we contribute to practice-oriented crisis informatics research that is committed to strengthening socio-technical resilience. Meanwhile, our study emphasizes the need for broad and critical analysis of technologically mediated human interactions in crisis situations. Such future endeavors of crisis informatics may build on feminist or intersectional HCI perspectives and thus provide insight into how social structures play into the success or failure of crisis volunteering. Understanding respective interactions on social media as representative of collective care work allows the emphasis of their importance to societal peace and the evaluation of not only settings but also ideas of care ethics.

References

Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet & Society. (2020). Corona culture [Accessed: December 1, 2020]. https://www.hiig.de/en/corona-culture/

Amaya, A., Bach, R., Keusch, F., & Kreuter, F. (2019). New data sources in

social science research: Things to know before working with Reddit data.

Social Science Computer Review, 35 (5), 1 – 10.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439319893305

Amir, S. (2018). Introduction: Resilience as sociotechnical construct.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8509-31

Amrute, S. (2019). Of techno-ethics and techno-affects. Feminist Review, 123 (1), 56 – 73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141778919879744

Auferbauer, D., & Tellioğlu, H. (2019). Socio-technical dynamics: Cooperation of emergent and established organisations in crises and disasters. CHI ’19: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, Scotland, UK, 4 May – 9 May 2019, 1 – 13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300448

Balka, E., & Wagner, I. (2020). A historical view of studies of women’s work. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 30 (2), 1 – 55.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-020-09387-9

Bennett, C. L., & Rosner, D. K. (2019). The promise of empathy: Design, disability, and knowing the “other”. CHI ’19: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, Scotland, UK, 4 May – 9 May 2019, 1 – 13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300528

Bennett, C. L., Rosner, D. K., & Taylor, A. S. (2020). The care work of access. CHI ’20: Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, 25 April – 30 April 2020, 1 – 15.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376568

Bitkom. (2020). Smart city index 2020: Wie digital sind Deutschlands Städte? [Accessed: December 11, 2020]. https://www.bitkom.org/Smart-City-Index

Bødker, S., Fox, S., Lalone, N., Marathe, M., & Soden, R. (2023). (Re)connecting history to the theory and praxis of HCI. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact., 30 (2). https://doi.org/10.1145/3589804

Briton, N. J., & Hall, J. A. (1995). Beliefs about female and male nonverbal communication. Sex Roles, 32 (1-2), 79 – 90.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01544758

Cadesky, J., Smith, M. B., & Thomas, N. (2019). The gendered experiences of local volunteers in conflicts and emergencies. Gender & Development, 27 (2), 371 – 388. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2019.1615286

Cheong, M., Leins, K., & Coghlan, S. (2021). Computer science communities: Who is speaking, and who is listening to the women? using an ethics of care to promote diverse voices. FAccT ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Virtual Event, 21 June – 24 June 2021, 106 – 115. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445874

Despret, V. (2013). Responding bodies and partial affinities in human-animal worlds. Theory, Culture & Society, 30 (7-8), 51 – 76.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413496852

Deutsche Welle. (2020a). City of Hanover overhauls gender language usage in official texts [Accessed: December 11, 2020]. https://www.dw.com/en/city-of-hanover-overhauls-gender-language-usage-in-official-texts/a-47188002

Deutsche Welle. (2020b). Coronavirus: Germany’s new face mask regulations explained [Accessed: September 2, 2021]. https://www.dw.com/en/coronavirus-germanys-new-face-mask-regulations-explained/a-53260732

Deutsche Welle. (2020c). Coronavirus: How Germany is showing solidarity amid the outbreak [Accessed: September 17, 2020].

https://www.dw.com/en/coronavirus-how-germany-is-showing-solidarity-amid-the-outbreak/a-52763215

Duden. (2020). Geschlechtergerechter sprachgebrauch [Accessed: December 11, 2020]. https://www.duden.de/sprachwissen/sprachratgeber/Geschlechtergerechter-Sprachgebrauch

Erete, S., Rankin, Y., & Thomas, J. (2023). A method to the madness: Applying an intersectional analysis of structural oppression and power in HCI and design. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact., 30 (2).

https://doi.org/10.1145/3507695

Fosch-Villaronga, E., Poulsen, A., Søraa, R. A., & Custers, B. (2021). Gendering algorithms in social media. SIGKDD Explor. Newsl., 23 (1), 24 – 31. https://doi.org/10.1145/3468507.3468512

Gui, X., Kou, Y., Pine, K., Ladaw, E., Kim, H., Suzuki-Gill, E., & Chen, Y. (2018). Multidimensional risk communication: Public discourse on risks during an emerging epidemic. CHI ’18: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21 April – 26 April 2018, 1 – 14. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173788

Harmon, E., Korn, M., & Voida, A. (2017). Supporting everyday philanthropy: Care work in situ and at scale. CSCW ’17: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Portland, OR, 25 February – 1 March 2017, 1631–1645.

https://doi.org/10.1145/2998181.2998330

Heeks, R., & Ospina, A. V. (2018). Conceptualising the link between information systems and resilience: A developing country field study. Information Systems Journal, 29. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12177

Held, V., Held, D., & Press, O. U. (2006). The ethics of care: Personal, political, and global. Oxford University Press, USA.

https://doi.org/10.1093/0195180992.001.0001

Helms, K., & Fernaeus, Y. (2021). Troubling care: Four orientations for wickedness in design. DIS ’21: Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2021, Virtual Event, USA, 28 June – 2 July 2021, 789 – 801.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3461778.3462025

Hootsuite. (2021). 27 Facebook demographics to inform your strategy in 2021 [Accessed: September 5, 2021].

https://blog.hootsuite.com/facebook-demographics/

Horgan, D., Hackett, J., Westphalen, C. B., Kalra, D., Richer, E., Romao, M., Andreu, A. L., Lal, J. A., Bernini, C., Tumiene, B., Boccia, S., & Montserrat, A. (2020). Digitalisation and COVID-19: The perfect storm. Biomed Hub, 5 (3), 43 – 65. https://doi.org/10.1159/000511232

Huang, Y. L., Starbird, K., Orand, M., Stanek, S. A., & Pedersen, H. T. (2015). Connected through crisis: Emotional proximity and the spread of misinformation online. CSCW ’15: Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14 March – 18 March 2015, 969 – 980. https://doi.org/10.1145/2675133.2675202

Karusala, N., Ismail, A., Bhat, K. S., Gautam, A., Pendse, S. R., Kumar, N., Anderson, R., Balaam, M., Bardzell, S., Bidwell, N. J., Densmore, M., Kaziunas, E., Piper, A. M., Raval, N., Singh, P., Toombs, A., Verdezoto, N., & Wang, D. (2021). The future of care work: Towards a radical politics of care in CSCW research and practice. CSCW ’21: Companion Publication of the 2021 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Virtual Event, USA, 23 October – 27 October 2021, 338 – 342. https://doi.org/10.1145/3462204.3481734

Key, C., Browne, F., Taylor, N., & Rogers, J. (2021). Proceed with care: Reimagining home IoT through a care perspective. CHI ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

Virtal Event, 8 May – 13 May 2021, 1 – 15.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445602

Kou, Y., Gui, X., Chen, Y., & Nardi, B. (2019). Turn to the self in human-computer interaction: Care of the self in negotiating the human-technology relationship. CHI ’19: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, Scotland UK, 4 May – 9 May 2019, 1 – 15. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300711

Lachance, E. L. (2020). Covid-19 and its impact on volunteering: Moving towards virtual volunteering. Leisure Sciences, 43 (1 – 2), 1 – 7.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1773990

Müller, G., Koslowski, T. G., & Accorsi, R. (2013). Resilience – a new research field in business information systems? In W. Abramowicz (Ed.), Business information systems workshops (pp. 3 – 14). Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg.

Murphy, M. (2015). Unsettling care: Troubling transnational itineraries of care in feminist health practices. Social Studies of Science, 45 (5), 717 – 737. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312715589136

Palen, L., Anderson, J., Bica, M., Castillos, C., Crowley, J., Díaz, P., Finn, M., Grace, R., Hughes, A., Imran, M., Kogan, M., LaLone, N., Mitra, P., Norris, W., Pine, K., Purohit, H., Reuter, C., Rizza, C., St Denis, L.,

. . . Wilson, T. (2020). Crisis Informatics: Human-Centered Research on Tech & Crises (tech. rep.) (Accessed: January 12, 2021).

https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02781763

Piccolo, L. S. G., Meesters, K., & Roberts, S. (2018). Building a socio-technical perspective of community resilience with a semiotic approach. In K. Liu, K. Nakata, W. Li, & C. Baranauskas (Eds.), Digitalisation, innovation, and transformation (pp. 22 – 32). Basel: Springer International Publishing.

Pipek, V., Liu, S., & Kerne, A. (2014). Crisis informatics and collaboration: A brief introduction. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-014-9211-4

Pipek, V., Palen, L., & Landgren, J. (2012). Workshop summary: Collaboration & crisis informatics. CCI’2012: Proceedings of the ACM 2012 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work Companion, Seattle, WA, 11 February – 15 February 2012, 13 – 14.

https://doi.org/10.1145/2141512.2141520

Purohit, H., Hampton, A., Bhatt, S., Shalin, V. L., Sheth, A. P., & Flach, J. M. (2014). Identifying seekers and suppliers in social media communities to support crisis coordination. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 23 (4 – 6), 513 – 545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-014-9209-y

Reuter, C., Heger, O., & Pipek, V. (2013). Combining real and virtual volunteers through social media. In T. Comes, F. Fiedrich, S. Fortier, J. Geldermann, & T. Müller (Eds.), Iscram ’10: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, Siegen, Germany, 12 May – 15 May 2013 (pp. 780 – 790). Karlsruher Institut für Technologie.

Reuter, C., Hughes, A. L., & Kaufhold, M.-A. (2018). Social media in crisis management: An evaluation and analysis of crisis informatics research. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 34 (4), 280 – 294. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2018.1427832

Reuter, C., Kaufhold, M.-A., Schmid, S., Spielhofer, T., & Hahne, A. S. (2019). The impact of risk cultures: Citizens’ perception of social media use in emergencies across Europe. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 148 (100), 1 – 17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.1

Schlesinger, A., Edwards, W. K., & Grinter, R. E. (2017). Intersectional HCI: Engaging identity through gender, race, and class. CHI ’17: Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, 6 May – 11 May 2017, 5412 – 5427.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025766

Schmidt, K., & Bannon, L. (1992). Taking CSCW seriously: Supporting articulation work. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 1 (1), 7 – 40. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00752449

Soden, R., Budhathoki, N., & Palen, L. (2014). Resilience-building and the crisis informatics agenda: Lessons learned from open cities, Kathmandu. ISCRAM.

Soden, R., & Palen, L. (2018). Informating crisis: Expanding critical perspectives in crisis informatics. CSCW ’18: Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, New York, NY, 3 November – 7 November 2018, 1 – 22. https://doi.org/10.1145/3274431

Tambo, E., Kazienga, A., Talla, M., CF, C., & C., F. (2017). Digital technology and mobile applications impact on Zika and Ebola epidemics data sharing and emergency response. Journal of Health and Medical Informatics,

8 (2), 254 – 261. https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7420.1000254

Taylor, M., Wells, G., Howell, G., & Raphael, B. (2012). The role of social media as psychological first aid as a support to community resilience building. The Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 27 (1), 20 – 26. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.046721101149317

Tellioğlu, H., Lewkowicz, M., Pinatti De Carvalho, A. F., Brešković, I., & Schorch, M. (2014). Collaboration and coordination in the context of informal care. CCCiC ’14: Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, Baltimore, Maryland, USA, 25 February – 1 March, 339 – 342. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556420.2558862

The Guardian. (2021). France may follow Germany in making clinical masks mandatory [Accessed: September 2, 2021].

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/20/france-may-follow-germany-in-making-clinical-masks-mandatory

Thebault-Spieker, J., Xu, A., Chen, J., Mahmud, J., & Nichols, J. (2016). Exploring engagement in a “social crowd” on Twitter. CSCW ’16: Pro- ceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing Companion, San Francisco, CA, 27 February – 2 March 2016, 417 – 420. https://doi.org/10.1145/2818052.2869112

Thieme, A., Vines, J., Wallace, J., Clarke, R. E., Slov´ak, P., McCarthy, J., Massimi, M., & Parker, A. G. G. (2014). Enabling empathy in health and care: Design methods and challenges. CHI EA ’14: CHI ’14 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 26 April – 1 May 2014, 139 – 142.

https://doi.org/10.1145/2559206.2559237

Toombs, A., Dow, A., Vines, J., Gray, C. M., Dennis, B., Clarke, R., & Light, A. (2018). Designing for everyday care in communities. DIS ’18: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM Conference Companion Publication on Designing Interactive Systems, Hong Kong, China, 9 June – 13 June 2018, 391 – 394. https://doi.org/10.1145/3197391.3197394

Tronto, J. (1993). Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. London: Routledge.

Vyas, D. (2019). Altruism and wellbeing as care work in a craft-based maker culture. CSCW ’19: Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, Austin, TX, 9 November – 13 November 2019.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3361120

Waterloo, S. F., Baumgartner, S. E., Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2018). Norms of online expressions of emotion: Comparing Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp. New Media & Society, 20 (5), 1813 – 1831. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817707349

Williams, J. (2000). From difference to dominance to domesticity: Care as work, gender as tradition. Chicago Kent Law Review, 76 (3), 1441 – 1493.

Wilson, T., Zhou, K., & Starbird, K. (2018). Assembling strategic narratives: Information operations as collaborative work within an online community. CSCW ’18: Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, New York, NY, 3 November – 7 November 2018, 1 – 26. https://doi.org/10.1145/3274452

Wired. (2020). Amid social distancing, neighbors mobilize over Facebook [Accessed: September 17 2020]. https://www.wired.com/story/coronavirus-social-distancing-neighbors-mobilize-facebook/

Yu, B., Seering, J., Spiel, K., & Watts, L. (2020). “Taking care of a fruit tree”: Nurturing as a layer of concern in online community moderation. CHI EA ’20: Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honululu, HI, USA, 25 April – 30 April 2020, 1 – 9. https://doi.org/10.1145/3334480.3383009

7 Appendix

Table 4: Coding scheme capturing activities of crisis volunteering, use of language and technology, and behavior reflecting and challenging social structures.

|

Level 1 |

Level 2 |

Level 3 |

|

Volunteering |

Information, Pets Support, Food, Community, Housekeeping, Delivery, Shopping, Sewing, Transportation, Mental Support, Child Care, Technical Work, Organizing Local Management, Education, Donation, Culture, Other Support, Legal Aid, Cooking, Financial Help, IT Support, Advice |

|

|

Technology |

Community Actions System Functions Analog Virtual |

Mention, Admin Moderation, User Demand, Direct Message Hashtag, Link, Image, Visual Lettering |

|

Language |

Emotional Formal, Indirect Appeal, Direct, Presumption, Capitalization, Incorrect, Abbreviation |

Anger, Resignation, Irony, Happy, Concern, Compliment, Farewell Greeting, Thankful, Metaphor Neologism Flowery, Emoticon, Mark, Confusion, Sad, Polarization Conspiracy, Curse Word, Knows It All, Passive Aggressiveness, Fun, Rhetorical Question, Dialect |

|

Performativity |

Gender-Sensitive, Intersectionality, Binary Gender, Individual Initiative, Naturalization, Hierarchy Work, Resistance Awareness |

Volunteering |

Table 5: Examples of labeled Facebook posts to which we have referred indirectly in our analysis (non-exhaustive overview).

|

File |

Quote |

Code |

|

Munich-12 |

‘Parents of children with disabilities find their limits regarding child care in 2020. It’s the same with us :D. Maybe there is someone here who has a pedagogical instinct, humor, and serenity who wants to look after our autistic teenage son (...) 1-2 times a month on a long- term basis.’ |

Child Care, User Demand |

|

Reddit-4e |

‘Tell her you don’t want to talk about it to her. If she still insists on it, I would turn around and go away. Everything else is useless and just reinforces her against-attitude.’ |

Advice, Direct |

|

Reddit-2b |

‘Recently, I have become extremely depressed and sad in the evenings. And that escalated just in the first weeks of the isolation due to COVID. I didn’t get out of bed for days (...).’ |

Emotional |

|

Hamburg-208 |

‘Not only old people have those fears; I am 51 and have a chronic illness, and because of the massive problems with my lungs, if I get infected there would be no rescue for me!’ |

Concern, Intersectionality |

|

Hamburg-45 |

‘Can somebody report [@username] to the admins, because I don’t know how it works.’ |

Confusion, User Demand |

|

Darmstadt-I-29 |

‘@[username] could you please offer your help once more under this post, so it doesn’t get confusing within the group?’ |

Admin Moderation |

Acknowledgements

This research work has been funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and the Hessian Ministry of Higher Education, Research, Science and the Arts within the scope of their joint support for the National Research Center for Applied Cybersecurity ATHENE. The work has also been supported by the LOEWE initiative (Hesse, Germany) in the context of the center emergenCITY and by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) as part of TraCe, the “Regional Research Center Transformations of Political Violence” (01UG2203E).

Date received: November 2022

Date accepted: May 2023

1 During the observation period, self-tailored masks were used for protection in public spaces (Deutsche Welle, 2020b). Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, both the federal government and states pronounced the greater effect of clinical masks and assured their supply as well as respective legal clarifications (The Guardian, 2021). Thus, as of 2022, sewing one’s own mouth-nose protection has stopped trending.

2 Traditionally, the German language has relied on the generic masculine form only or, for some years now, both the masculine and feminine form, foregrounding binary conceptions of gender when referring to, for example, doctors as “Arzt” (masculine form) and “Ärztin” (feminine form) or citizens as “Mitbürger” (masculine form) and “Mitbürgerinnen” (feminine form) or using the “internal-I” to describe residents of Darmstadt as “DarmstädterInnen” (Reddit-3i, Darmstadt-I-115, Darmstadt-I-116). More recently, the gender star (*), the underscore character (representing the “gender gap”), and semi-colons have been introduced as textual concepts that can be used to produce gender-sensitive language in German, as demonstrated by our data, which sees music teachers described as “Musiklehrer*innen” (Hamburg-92), moderators described as “Moderator_innen” (Cologne-1), and Munich residents described as “Münchener:innen” (Munich-101). These terms include all gender identities (Deutsche Welle, 2020a; Duden, 2020).

Metrics

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Stefka Schmid, Laura Gianna Guntrum, Steffen Haesler, Lisa Schultheiß, Christian Reuter (Author)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.