Pay Cashless and Be Clueless About Your Data?

Navigating Tensions of Data Use in Digital Payments

1 Introduction

“Are you paying with cash or by card?” has become a familiar question to many at the checkout counter. More and more frequently, the answer is “by card” or an option other than cash. Payments at the point of sale (POS) are shifting to the digital sphere1 , considering that the share of digital transactions2 in Europe increased from 26% in 2019 to 37% in 2022 (ECB, 2022, p. 12 – 13)3 . Like all actions in the digital sphere, digital payments leave data traces; however, little is known about the data processed and used for making a digital payment.

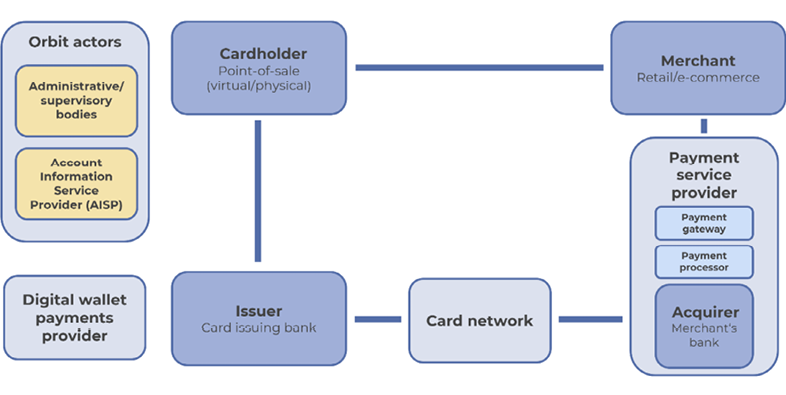

Although paying digitally is simple for the consumer, the process behind a digital payment is not. Many steps are required to facilitate a digital payment between a consumer and a merchant. Consequently, payment data travels far along the payment processing chain. When a customer, called Edith, makes a payment at a physical or online shop, the entities involved are (at a minimum) the issuing bank (Edith’s bank), acquiring bank (i.e., the merchant’s bank), the card network (e.g., Visa, Mastercard, or a domestic scheme like girocard in Germany), and a payment service provider (PSP4 ; which connects merchants to the payment infrastructure). An exchange of money that appears to take place between two entities in fact involves a multitude of actors behind the scenes.

The complexity and the number of players in digital payments have created a competitive market driven by financial digitalization, which is nonetheless often regarded as unprofitable, especially in the euro area (Brandl et al., 2024, p. 740 – 741; Leibbrandt et al., 2021, p. 117 – 119). In this context, monetizing payment data appears to be a clear path to profitability (Ernst & Young, 2021). However, the decision to monetize data must consider the regulatory environment, which includes both preserving privacy and regulations enabling law enforcement, including anti-money laundering (AML) and countering the financing of terrorism (CFT).

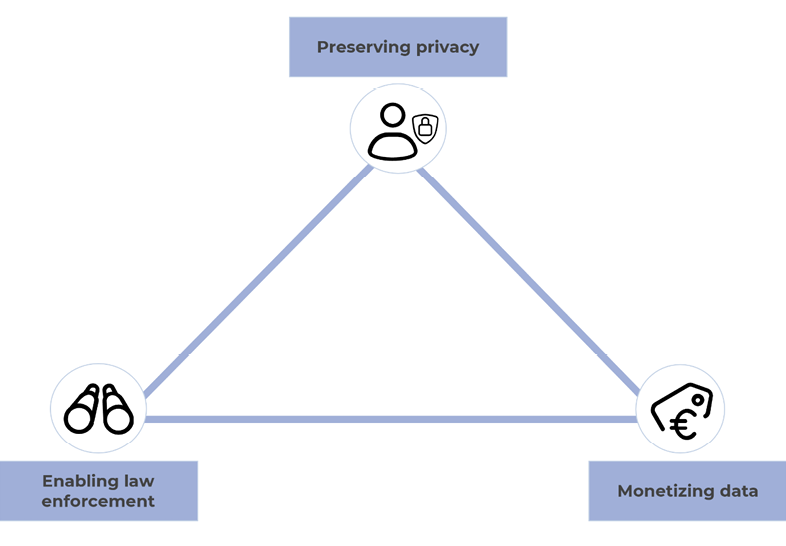

Zooming out, payment data affect three key objectives: preserving privacy, monetizing data, and enabling law enforcement. Once adapted to payment data use, these objectives can be analyzed through the lens of the data governance trilemma introduced by Zygmuntowski (2023). To this end, the present paper first maps the different actors, the roles they play along the payment processing chain, and how they use data.

The data governance trilemma is employed as an analytical framework to examine how preserving privacy, enabling law enforcement, and monetizing data are balanced. More specifically, the paper aims to answer the following research questions: (1) How is payment data used along the payment processing chain? (2) How does this relate to the challenges posed by the data governance trilemma? The analysis focuses on monetizing data and builds on previous research at the nexus of payment data use and law enforcement (e.g., Lagerwaard, 2018; Lagerwaard et al., 2023). Preserving privacy serves as a benchmark against which the other objectives can be measured.

The findings of this research may inform the discussion about the future of payments and the development of a central bank digital currency (CBDC), currently envisaged by the European Central Bank (ECB)5 as a privacy-preserving digital euro. As emphasized by Fabio Panetta (2022), a former Member of the Executive Board of the ECB (2020–2023), “it is not surprising that people expect payments in digital euro to guarantee high privacy standards. As payments go digital, private companies are increasingly monetising payment data” (Panetta, 2022).

The sources used for this research are European legislation, legal cases, and reports/research publications of the payment industry and public actors (e.g., European institutions and data protection authorities). Semi-structured interviews6 with regulators and payment industry experts, as well as attendance at public events organized by the payment industry, provided additional insights.

The first section introduces the data governance literature, the data governance trilemma, and how it relates to payment data. It also proposes a working definition of payment data. The second section then describes the payment processing chain based on the four corners model. The model serves as a template for the subsequent analysis of card-based payments and related methods, such as digital wallet payments. This analysis also considers actors who use payment data without being directly involved in the payment processing, for instance, to fulfil their mandate or establish business models based on payment data. The analysis focuses on a fictional customer, named Edith, as the data subject and origin of payment data, tracing its use along the payment processing chain. In doing so, it sheds light on the barriers to preserving privacy and analyzes the implications of data use through the lens of the data governance trilemma.

2 Data Governance and Its Inherent Trilemma with Payment Data

It is difficult to find an entry point for research on payment data, which is intangible, yet contested and highly valuable. From the outside, data flows appear opaque, and understanding what kind of data is used by whom and how, as well as under what regulatory requirements, may seem challenging. The scholarly debate proposes different ways of looking at data.

Zuboff (2019) described the practice of collecting and analyzing data to predict or adapt customer behavior for profit maximization. In this context, she coined the term “surveillance capitalism” to denote the erosion of individual autonomy and the risks it poses to social life. Meanwhile, Bigo et al. (2019) focused on public actors and the “surveillance assemblage” they form by creating a pervasive system of surveillance and control through data collection technologies. Although they shed light on the exploitative practices implemented for the sake of economic gain and showed how public actors use data for surveillance purposes, the researchers did not produce a comprehensive and analytical account of data use practices.

In a complex network managing a shared resource and making decisions about how to use payment data, data governance approaches help to categorize the relevant actors and outline the underlying governance structure. A deeper understanding of this structure reveals the presence of multiple interests, each pursuing different objectives that must be carefully balanced. The present research delineates the basic concepts of data governance to then introduce the data governance trilemma conceptualized by Zygmuntowski (2023), which provides a distinct perspective on the ethical implications of data use practices and can be adapted to the present research.

2.1 Data Governance – What is it?

To borrow Hamlet’s quandary, to use or not to use data, that is the question. In the case of payment data, it refers to a situation where business decisions about data use are made deliberately and to mitigate unforeseen consequences. In essence, data governance seeks to create value from data while minimizing associated risks, such as fines for regulatory non-compliance or inaccuracies in decision-making due to data quality issues (Abraham et al., 2019). The use or non-use of data revolves around the question of whether “it is possible to determine whether exploiting the value of data and controlling its risks is worth the costs” (von Grafenstein, 2023, p. 18).

Thus, data governance enables data use by providing the overarching framework that sets the rules and standards. A structured literature review by Abraham et al. (2019) revealed that a clear overall definition is missing. This may not be surprising given the broad scope of the concept, the constant emergence of new technologies, and the fact that the regulatory environment is still in the making. The authors nonetheless proposed a definition based on the literature reviewed7 :

Data governance specifies a cross-functional framework for managing data as a strategic enterprise asset. In doing so, data governance specifies decision rights and accountabilities for an organization’s decision-making about its data. Furthermore, data governance formalizes data policies, standards, and procedures and monitors compliance. (Abraham et al., 2019, p. 425 – 426)

Framing data as a “strategic business asset” signals that the underlying goal of data governance is to create economic value from data. The economic perspective dominates the literature and has “skewed [data governance] towards economic value, and contestability of such regime was diminished for many years” (Zygmuntowski, 2023, p. 8). However, other dimensions of data governance are included in the definition. In particular, monitoring compliance refers to mechanisms for ensuring that standards and data policies are followed. Given that these standards and data policies originate from regulatory frameworks, ethical and societal considerations are also part of the equation and must be taken into account in addition to economic drivers.

In fact, the initial question still revolves around whether or not to use data, but the context must be examined more closely to embed the issue of payment data in the data governance trilemma and analyze the interests involved along the payment processing chain. To this end, the next section explores the relationship between payment data and the various objectives of its use.

2.2 The Data Governance Trilemma and Its Nexus with Payment Data

Without data, there would be no digital payments. However, payment data attracts interest and is therefore not immune to exploitation by private entities, such as banks, fintech, big tech, and merchants, seeking to leverage it for profit. Meanwhile, public actors strive to expand their capacity to fulfil their mandate more effectively. A very important variable is left out here, the data subject, whose right to privacy is at stake. Art. 4(1) of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) defines a data subject as “an identified or identifiable natural person.” In the present research, a fictional individual, Edith, represents data subjects. Balancing the interests of these diverse actors involves three interrelated objectives, summarized by Zygmuntowski (2023, p. 2) as the data governance trilemma: protecting fundamental rights, serving the public interest, and generating economic value. None of these objectives is exclusive or stands on its own. The pursuit of one alone may be to the detriment of the other, so a delicate balance needs to be found to ensure that none overshadows the others.

Adapting the terms originally chosen by Zygmuntowski (2023) to the objectives of digital payments, the three following objectives are identified: preserving privacy, given that the individual’s privacy is at stake when data is processed for a variety of purposes in a non-transparent manner; enabling law enforcement, as an objective representing a particular strand of the public interest; monetizing data to facilitate or sustain data-driven business models (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Visualization of the data governance trilemma in payment data (Source: Author)

Note: The icons used are the result of an interdisciplinary research project on the design of understandable privacy information (von Grafenstein et al., 2024). The icons were retrieved from: https://github.com/Privacy-Icons/Privacy-Icons

The inherently different objectives of legal frameworks regulating payments reveal the tension in the payment landscape and will serve as a basis for the analysis (see Section 2). The GDPR represents the objective of preserving privacy, which enacts individuals’ right to privacy and requires financial intermediaries to safeguard any personal data collected, including for business purposes. The Law Enforcement Directive8 pursues the objective of enabling law enforcement by allowing data processing that goes beyond the GDPR but is limited to competent authorities. Similarly, regulations to combat illicit financial flows through the 5th Anti-Money Laundering (AML) Directive, requires financial intermediaries to collect and store large amounts of data to be transmitted to financial intelligence units (FIUs) for further investigation. Lastly, the second Payment Services Directive (PSD2)9 reflects the objective of data monetization by driving innovation and promoting competition in the payments landscape. This includes the obligation for financial intermediaries to give access to their customers’ account information to third-party providers, referred to in PSD2 as account information service providers (AISPs).10 Given the trilemma and the simultaneous pursuit of these underlying objectives, the fulfilment of these legal requirements can be “difficult to incorporate within the same technological and governance structure” (Ferrari, 2023, p. 62).

Before moving on to the payment processing chain, the next section examines the definition of payment data and how different methods for using it relate to enabling law enforcement and monetizing data within the data governance trilemma. A dedicated look at preserving privacy is taken in Section 2.1 and is directly linked to the cardholder as the initial stage in the payment processing chain. In contrast to monetization or law enforcement, privacy is not concerned with the use of data. Instead, it focuses on ensuring the optimal protection of data subjects, like Edith, while also enabling the appropriate and compliant use of data.

2.3 Digital Payment Data and Its Purposes

“Payment data does not lie.” The statement, uttered at a financial sector event, captures one of the key characteristics that make payment data particularly valuable. Compared to other types of data, payment data is uniquely linked to an individual’s purchasing decisions and directly reflects an interest significant enough to warrant a financial transaction.11 This section provides a working definition of payment data and examples of how data is used for monetization and to enable law enforcement. Preserving privacy is discussed in more detail in Section 2.1.

Legislation in the European Union lacks a clear definition of payment data (see Ferrari, 2023, p. 64). The PSD2’s Art 4(32) defines sensitive data as “data, including personalized security credentials which can be used to carry out fraud,” which mainly reflects the security aspects of payments. According to a payment expert interviewed for this research, the lack of a clear definition can be attributed to the continuous evolution of payments: “the means of payment were initially not regulated, they simply developed on the market. As a result, they have created their own field structure, using the data that is required to process a payment method” (Payment expert, personal communication, August 23, 2024). The situation is different in the United Kingdom, where the British Payment System Regulator (2018) defines payment data as

the totality of the information collected by PSPs and other entities in the process of providing payment services to end-users. This includes data that is provided as part of providing core payment services to end-users and the “ancillary data” often collected as the payment is being processed. (p. 16)

Given this broad definition, a more nuanced categorization helps to capture different payment situations. The Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL), the French data protection authority, distinguishes more precisely between types of data: “actual payment data” is data being necessary to enable core payment services, and data generated and processed beyond this scope are categorized as “purchase and checkout data” and “contextual and behavioural data” (CNIL, 2021, p. 10). Examples for each of these categories are presented below, although the boundaries between categories are somewhat blurry.

Table 1: Three categories of payment data (CNIL, 2021, p. 10)

|

Payment data |

|

|

Actual payment data |

Payment amount, date/time, payer/payee identity, means of payments (e.g., card network), IBAN – International Bank Account Number (lasered on cards), PAN – Primary Account Number (usually embossed on cards), and fraud prevention score. |

|

Purchase and checkout data |

Characteristics of purchased goods, place linked to the date of purchase, loyalty programs, etc. |

|

Contextual and behavioral data |

Customer knowledge data (purchase history), characteristics of (virtual) point of sale (e.g., payment terminal or virtual terminal in ecommerce), browsing behavior, etc. |

Data has inherent value, but this value is not automatically realized. In fact, “large volumes of data would bear no economic or social value – and no consequences for financial services consumers – if they were not matched by increasing analytical capacities” (OECD, 2020, p. 12). As a result, different types of data are used for various purposes, which are categorized in this research into monetizing data and enabling law enforcement. The lists below offer an overview of the purposes related to the aforementioned objectives; because the field is constantly evolving, the tables are not exhaustive.12

Table 2: Monetization of payment data (Ferrari, 2020; OECD, 2020; Weber et al., 2023)

|

Monetizing data |

|

|

Customer profiling |

Valuable insights through a variety of data sources enabling detailed customer segmentation for targeted marketing. |

|

Risk assessment |

Integration of diverse data points for credit scoring to improve the assessment of risk of default or higher accuracy for insurance offers. |

|

Robo-advice |

The processing of payment and broader financial data can be used to develop a personalized financial plan. |

|

Account aggregation |

API (Application Programming Interface) enabled aggregation of data from different bank accounts for improved financial management. |

|

Fraud detection |

Monitoring of large amount of payment data may help detect fraudulent activities. |

Table 3: Uses of payment data to enable law enforcement? (Ferrari, 2020; OECD, 2020; Weber et al., 2023)

|

Enabling law enforcement |

|

|

Combating anti-money laundering |

Monitoring and analyzing spending patterns to detect unusual or suspicious activities that could indicate money laundering. |

|

Countering the financing of terrorism |

Examining transaction behaviors to uncover anomalies that suggest the flow of funds to terrorist groups, mainly for cross-border payments. |

|

Tax evasion |

Tax authorities receive and evaluate payment data for tax fraud investigations. |

These concrete examples, grouped under the two objectives of monetizing data and enabling law enforcement, illustrate the diverse uses of payment data, which often involve multiple actors in their implementation. These expanded uses of data are enabled through the granular data that is categorized above. The objective of preserving privacy is discussed in more detail in Section 2.1, along with the challenges associated with assessing and achieving it.

3 Data Use in the Payment Processing Chain: The Four Corners Model and Beyond

The chain metaphor visually represents the sequential process of a digital payment. At the very beginning of the chain is Edith, the data subject, who initiates the payment. The goal is to examine how data is processed from this point forward, particularly in relation to the data governance trilemma (see Figure 1). However, tracking the data of a digital payment is challenging. As the story below shows, multiple actors are involved in facilitating a simple payment:

Edith (i.e., the cardholder) decided to buy medicine from a local pharmacy and from an online pharmacy because not all the medicine was rightly available. They presented their card at the local pharmacy and provided personal details and debit card information to the online pharmacy. The two pharmacies (i.e., the merchants) then transmitted Edith’s payment details via a PSP (payment service provider) to the merchant’s bank (i.e., the acquirer). The acquirer then sent an authorization request to Edith’s bank (i.e., the issuer), which issued the card through a communication network (i.e., the card network). For the online purchase, Edith was redirected to an authentication page; in contrast, the in-person payment at the pharmacy did not require authentication. Visa processed the authorization response for both payments, sending it from the issuer back to the acquiring bank and, ultimately, to the online pharmacy, confirming Edith’s payment. (Source: Author)

This basic architecture of a card-based payment, also known as the four corners model, includes the cardholder, the cardholder’s bank (“the issuer”), the merchant, and the merchant’s bank (“the acquirer) (Bindseil et al., 2023, p. 37). In addition to these four corners, a card network and a PSP are generally required for a payment to proceed (CNIL, 2021, p. 29). In the context of this research, these are complemented by providers of digital wallet payments and orbit actors, that is, actors who operate outside the payment processing chain and use data to enable law enforcement or develop use cases based on data, e.g. aggregating account information from multiple bank accounts.

To clarify the paths of data within the payment processing chain, the roles of the actors involved must be analyzed. This includes their data availability, data use, and how this relates to the data governance trilemma. The analysis therefore follows Figure 2, starting with (1) the cardholder and the inherent barriers to preserving privacy. It highlights the challenges of the research, as well as broader issues related to privacy and transparency. It also examines the role of each actor and how they exercise control over payment data, with a focus on the objectives of monetizing data and enabling law enforcement. The analysis then continues with (2) merchants, (3) PSPs, (4) the card network, and (5) banks, representing the issuer. Additionally, new actors are included, such as (6) digital wallet payment providers and (7) orbit actors, that is, FIUs and AISPs, which are attached to the payment processing chain.

Figure 2: Visualization of the payment processing chain, including “orbit actors” that process financial data related to their mandate or business model but are not directly involved in payment processing. (Source: Author)

3.1 The Cardholder: Principles of Data Processing and Inherent Barriers to Preserving Privacy

The payment processing chain begins when the cardholder, Edith, taps, inserts their card, or fills in their card credentials for an online purchase. Preserving privacy indicates that Edith’s data is not excessively processed and that they are in control over how their data is collected and used. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) sets out basic principles to prevent excessive data processing. These serve as a benchmark to assert the objectives enabling law enforcement and monetizing data (see Section 1.3), which are fundamentally dependent on or respond to Edith’s actions. However, recurring debates on privacy demonstrate that a lack of transparency persists, culminating in the consent paradox, consent is typically neither informed nor freely given (Bergemann, 2018).

The principles for the processing of personal data laid out in Art. 5 of the GDPR are key prerequisites for fulfilling the objective of preserving privacy. In particular, Art. 5(1b) states that personal data can be “collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes” and Art. 5(1c) establishes the data minimization principle, according to which personal data must “be adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which they are processed.”

Given the complexity and inherent opacity of the payment processing chain, the transparency obligations stated in Art. 12–14 of the GDPR are meant to give the data subject a clear understanding of which actor is processing data on their behalf (CNIL, 2021, p. 54 – 55). Yet, the principle of transparency is largely infringed upon in the case of digital payments, which restricts the ability to assess other principles, such as purpose limitation in Art. 5(1b) and data minimization in Art. 5(1c). In the words of a privacy official interviewed for this research, who recognized the limitations in the realm of payments, “all I can say is that, as a professional, I don’t have an overview of what data is being used. There are a lot of different players involved” (Privacy official, personal communication, January 26, 2024).

This results in a structural disadvantage for data subjects in asserting their rights. Examining consent mechanisms, Bergemann (2018) pointed out that consent is neither informed nor freely given and developed the “consent paradox.” Bergemann (2018) demanded a fundamental shift by “reintroducing a more compelling critique of power into data protection” (p. 21). Colaps et al. (2023) underscored this point, referencing the “fundamentals about power, where consent and other principles of data protection cannot operate in a radically unequal environment” (p. 192). In this context, the structural disadvantage of the data subjects in exercising their rights results from the virtual absence of informed consent and the emerging power imbalance between the data subject and the actors controlling and processing their data.

3.2 Merchants: The Two Worlds of e-Commerce and Physical Shops

After Edith initiates the payment by presenting their card (see Figure 2), payment data is generated on the merchant’s end. From then on, data availability differs significantly: more limited data is available for physical shops than for e-commerce. To bridge this gap, supermarket chains and other retailers have launched apps designed to collect customer data in physical locations. However, data availability is closely tied to data exclusivity. According to a privacy official, data is treated as an informational asset, enabling its monetization. Smaller businesses, in particular in e-commerce, may share their data in exchange for access to larger sales platforms. Consequently, preserving privacy may be increasingly inhibited due to ever more data collection spilling over from e-commerce to physical stores.

E-commerce enables more comprehensive data collection because the shopping process is embedded in the digital sphere. The data available through e-commerce offers deeper insights into customer behavior than that associated with physical stores. Given the diversity of e-commerce offerings, ranging from niche online shops to large platforms, no universal statement can be made about which data is available. Due to their versatility, all kinds of payment data may be collected, including actual payment data, purchase and checkout data, and contextual and behavioral data (see Section 1.3). To derive value from available data, it must be combined with analytical capabilities and a clear strategic approach.

In this regard, the analytic “model of relationing” offers a three-step approach to establishing economic relationships and thus provides valuable insights into how e-commerce uses customer data (Mützel et al, 2024, p. 2 – 4). The model explains the mechanisms and processes involved in using data to foster these relationships. “Entanglement” refers to tracking the behavior of a customer. Next, “dissection” concerns the analysis of browsing behavior and its transformation into a commodity. Lastly, interaction is transformed into “good matches”, i.e. based on the behavior and derived preferences the presentation of corresponding products, to perpetuate the economic relationship (Mützel et al, 2024, p. 2-4). In essence, it is an advancement of customer loyalty programs. Alrumiah et al. (2021) show that with successful adaptation, the extensive use of data helps to increase revenue, but the rapid growth of available data challenges merchants because profitable use relies heavily on data analysis skills.

In this context, data exclusivity, where data is retained solely as an informational asset for internal business operations, may be reconsidered if sharing enables access to a larger customer base by offering products on a broader marketplace. Along these lines, Poell et al. (2019) analyzed platformization, with e-commerce being one of the “poignant examples” (p. 6) of the effects of platform companies shaking up industry incumbents. While platformization may increase the revenue of smaller e-commerce shops, it gives major platforms gain competitive insights into the top-selling products or product categories of other online shops, which enables them to strategically adjust and expand their product portfolio.

Physical stores face a clear competitive disadvantage in terms of data availability due to their limited ability to track customer interactions or because of fragmented data collection. However, hybrid solutions aim to address this gap. Increasingly, physical stores are integrating digital payment systems to “assist in bringing foundational principles of the digital economy to brick-and-mortar shopping” (Mützel et al., 2024, p. 7). This approach is complemented by merchants rolling out payment apps, directly related to discounts only accessible to users of these apps to incentivize their use (CNIL, 2021, p. 42; Mützel et al., 2024). Moments of relationing are thus transferred to the world of physical stores: with each purchase via the app, the data generated about the customer allows merchants to enrich their database and develop data monetization strategies, such as loyalty programs.

Merchants often have a limited ability to handle all payment-related tasks independently. Only a few have set up their own payment platform.13 Instead, merchants typically rely on PSPs, which facilitate connections with various payment methods and assist merchants in managing databases, storing data securely, and optimizing how the information is used to support their business operations.

3.3 Payment Service Providers: Making Payments Happen for the Merchants

A few exceptions aside (see Section 2.2), PSPs help merchants access the payment infrastructure. PSPs facilitate the transmission of payment data, such as the transfer of Edith’s payment details to the merchant’s bank. Beyond facilitating transactions, PSPs also contribute to monetizing data by preparing payment data for further analysis. The available data may be actual payment data or more extensive data, and general statements cannot be made in this regard due to agreements between merchants and their PSPs. In any case, PSPs enable merchants to improve the “moments of relationing” (see Section 2.2) by offering dashboards with varying levels of granularity regarding a merchant’s customer base. Building on this, PSPs also make it possible to connect the databases of merchants who operate both e-commerce and physical stores. Previous unknowns become identifiable when successfully matched through the use of the same payment method. Therefore, PSPs can be understood as enabling merchants to monetize data, thereby enhancing business operations.

PSPs are inherently difficult to define due to their multifaceted nature and the wide scope of payment-related services they offer. They often integrate multiple services into a single solution. PSPs facilitate transactions at physical points of sale through payment terminals, allowing customers like Edith to insert their card, tap, or use their mobile phones. They also enable e-commerce by integrating virtual points of sale with software development kits. PSPs manage key steps in the payment process, including collecting and encrypting payment data as a payment gateway provider, performing initial checks for accuracy and fraud prevention, and then routing the payment request as a payment processor to the acquirer, typically the merchant’s bank. Although each role (payment gateway, fraud detection service provider, payment processor, and acquirer) can be performed by different actors, some PSPs unify them (e.g., Adyen, 2024; Stripe, 2023).

Providing a good service is at the core of PSPs’ business model, whose primary goal is to give merchants secure access14 to payment infrastructure. Nonetheless, the ability of merchants to make use of payment data is gaining importance. While basic payment data is essential for processing transactions, additional data can enhance fraud prevention and enable more effective analyses (CNIL, 2021, p. 42).

Further, the diversity of merchants (see Section 2.2) is reflected in the wide range of payment offerings, and PSPs address the diverse requirements by providing payment infrastructure tailored to their needs. These solutions range from payment terminals for a neighborhood kiosk to integrated payment platforms for fashion retailers like H&M operating both online and offline, or subscription-based business models like Netflix with recurring payments. For businesses operating in different spheres at the same time (i.e., in physical stores and online), payment services such as “omnichannel” or “unified commerce” solutions bundle payment data in one dashboard to provide merchants with a “holistic view of customer behaviour” and enable “more targeted and personalised marketing” (Stripe, n.d.). As a result, merchants can turn previously unknown insights into data that they can use to inform their data monetization strategy.

3.4 Card Networks: The Perks of Being the Man in the Middle

Connecting banks and standardizing their communication is the key task of card networks. For example, Edith’s bank chose to partner with one card network. Through this network, the payment between Edith’s bank (the issuing bank) and the merchant’s bank (the acquirer) is made possible (see Figure 2). In addition to ensuring the secure exchange of payment information, card networks also implement fraud prevention measures. This is true for international card networks like Visa, Mastercard, or American Express (AMEX) but also for national alternatives like girocard in Germany, Multibanco in Portugal or cartes bancaires in France. Over time, some card networks have expanded their business models and included data-driven marketing services. By monetizing data, they offer insights into consumer behavior, which allow businesses to target customers more effectively. However, this add-on raises privacy concerns and may limit the capacity to preserve privacy, particularly as concerns the processing of EU citizens’ data by non-European companies. The GDPR requires an adequacy decision for cross-border data transfers, which has repeatedly been overturned, in particular in the US. Yet another critical issue is the potential de-anonymization of supposedly anonymized transaction data, which threatens privacy.

Adequacy decisions are essential for enabling data transfers between the EU and non-EU countries, and many are already in place (European Commission, 2024). However, past adequacy frameworks have been invalidated inter alia due to a lack of providing “essentially equivalent” protection for data subjects that is guaranteed under the GDPR (European Parliament, 2020). Yet another concern, that was not part of the Schrems II judgement are concerns over surveillance laws in the US, such as the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act.15 The adoption of the EU–US Data Privacy Framework (European Commission, 2024a) aims to address these shortcomings, but legal scholars predict that an eventual Schrems III case, i.e. a ruling that builds on the Schrems II case, which invalidated the Privacy Shield, a previous adequacy decision by the European Commission (Barczentewick, 2023). These concerns underscore the uncertainty surrounding data transfers, including for customers who use card networks like Visa, Mastercard, or AMEX.

Card networks primarily use payment data for fraud prevention and security purposes, but there are also exceptions. For instance, the French data protection authority CNIL has highlighted that AMEX was among the first to transform payment data into a comprehensive marketing database (CNIL, 2021, p. 26). Similarly, Visa offers services like the Visa Analytics Platform, which uses aggregated and anonymized data to shed light on consumer behavior and spending patterns (Visa South East Europe, n.d.). Furthermore, Visa employs data analytics to drive digital targeting and customer acquisition (see Visa Consulting & Analytics, 2020). Mastercard follows a similar path with its Data & Services Division, which offers targeting solutions. In addition, the Mastercard Digital Engine was developed to detect microtrends, for instance, by matching new food trends with the preferences of consumers that are already known to the system (Rajamannar, 2023). Both Visa (n.d.) and Mastercard (n.d.) explicitly state in their privacy notes that they only use anonymized and aggregated data to run their marketing activities.

Despite this claim, the risk of de-anonymization remains a critical issue. Combining anonymized datasets with publicly available information significantly increases the likelihood that individuals can be re-identified. The European Data Protection Supervisor has outlined these risks in detail, emphasizing that de-anonymization techniques can compromise consumer privacy (EDPS et al., 2021). A study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology further supports these findings by illustrating how mobility data can help identify individuals with alarming accuracy (Kondor et al., 2020). The combination of multiple datasets, such as payment history, device data, and location information, makes it increasingly difficult to guarantee irrevocable anonymization, thus exposing consumers to potential privacy risks.

3.5 Banks: Data Use Practices Adaptations in Neobanks, Progress in Direct Banks, and Status Quo in Traditional Banks

In the payment processing chain, the issuing bank16 receives data on a payment from the relevant card network (see Figure 2). As one commercial bank employee put it, “in fact, a bank is made up only of data” (Commercial bank employee, personal communication, June 11, 2024), which makes them custodians of financial and payment data. The available data is, by design, limited to basic payment data, but it can also include customer data due to Know Your Customer requirements.

Banks can broadly be categorized along a spectrum based on their data use, with traditional banks on one end and neobanks on the other, although a definitive role description is not possible due to the diversity within and across bank categories. Traditional banks follow a one-stop-shop approach by offering a wide range of financial services with diverse revenue streams. They typically do not monetize payment data, and preserving privacy is thus part of their business model. Meanwhile, direct banks act as a hybrid between traditional banks and neobanks. They are increasingly adopting enhanced data analytics, especially in comparison to traditional banks. Lastly, neobanks adopt a fully digital-first approach, with no legacy infrastructure. As a result, they are more agile in their use of payment data and often integrate it into their business models for monetization.

The notion that change is the only constant in life is particularly evident in the financial sector, where traditional banks have been strongly affected by market shifts. Gabriel Makhlouf (2023), the Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland since 2019, has highlighted this, noting that the number of traditional banks has declined significantly. Historically, these banks acted as the main financial intermediaries, offering a wide range of services and relying on trust-based customer relationships (Temelkov, 2020). A commercial banker interviewed for this study summarized the approach to data management: “the data is simply there and is supplemented by additional transactions every day. They are then archived and documented in accordance with the existing regulations” (Commercial bank employee, personal communication, June 11, 2024).

This approach contrasts with newer banking models that use data analytics to monetize data, as well as new market entrants coming with the open banking movement (Westermeier, 2019). While this may relegate traditional banks to a purely infrastructural role, some are expanding their data analytics capabilities by partnering with or acquiring new players (CNIL, 2021, p. 33). However, some traditional banks that have attempted to embrace data-driven approaches have faced regulatory scrutiny. For instance, the European Data Protection Board reported a case in Lower Saxony, where a bank used payment data (among other data) for “smart data analytics,” which was found to be GDPR non-compliant after the competent authority weighed the interests involved and concluded that “the fundamental rights of customers prevailed” (EDPB, 2024, p. 45). As Denis Lehmkemper, Data Protection Commissioner of Lower Saxony, explained, “banks hold sensitive customer data and therefore have a high level of responsibility… we will continue to monitor this area closely” (EDPB, 2024, p. 45).

Although distinct, direct banks and neobanks share a common digital approach. Direct banks refer to themselves as incumbents because they emerged in the 1990s. They often rely on a hybrid model combining elements of both traditional banks and neobanks (BaFin, n.d.). Direct banks provide a more comprehensive range of banking services than neobanks and often retain some customer service via telephone. In contrast, neobanks have emerged as fully digital entities. Despite their structural differences, both direct banks and neobanks show an inclination towards monetizing data. New market entrants, particularly neobanks, have been especially active in using data for marketing in innovative ways, as highlighted by the CNIL (2021, p. 32), referring to the French Prudential Supervision and Resolution Authority. This is evident in Revolut’s (2025) privacy notice, for example, which states that if national laws require consent for marketing communications, it will be obtained in advance; this implies that data processing for marketing purposes is the default in other cases. Additionally, Revolut (2025) specifies that personal data is used for marketing, which “may include analysing how you use our services and your transactions.” Ferrari (2020, p. 523) confirms that neobanks use data for various marketing purposes and that the fluid nature of data governance processes means that there is a risk that data used for law enforcement purposes overlaps with data used for commercial purposes.

As new players continue to challenge market incumbents, regulatory scrutiny will play a crucial role in balancing innovation with privacy concerns and ensuring that the use of payment data remains both ethical and compliant. This will be particularly relevant to the development of big tech entering the financial services market with digital wallet payments.

3.6 Digital Wallet Payment Providers: From “Traditional” Payments to New Convenience with Hidden Trade-Offs

Increasingly, people pay with wallet-based solutions. Big tech solutions such as Apple and Google Pay are dominant where national solutions did not gain traction. Apple and Google Pay have built on existing financial infrastructures based on the four corners model, allowing payments without the presence of a physical card.17 Others, like PayPal, enable such payments but remain independent of the card network.18 A key issue is the lack of European alternatives, considering that all the aforementioned options are owned by non-European companies. Although national solutions exist, they have yet to facilitate eurozone-wide payments.

Some providers openly seek to monetize payment data, and others may emerge over time. While Google uses payment data to enrich its datasets, PayPal does so by default for marketing purposes and announced plans for their US business to build an advertising platform. In contrast, Apple prioritizes security at the expense of banks, and Wero19 , a European alternative rolled out gradually, promises a data-minimizing approach but has yet to prove its potential. An even more premature but also more promising initiative is the digital euro, a key project of the ECB. Its legal framework is currently being negotiated by European institutions. The objective of preserving privacy is therefore highly dependent on the underlying mobile operating system. European alternatives such as Wero or the digital euro show promise, but they must achieve a critical mass to compete effectively while maintaining a data-minimizing setup and thus preserving privacy.

Apple and Google Pay have different approaches: Apple provides a secure payment option, while Google takes advantage of its strategic position in payment streams to exploit the data generated. Apple employs the “manufacturer model” (CNIL, 2021, p. 37), which is costly for banks because they pay part of their commission to Apple. Conversely, Google follows the “service provider model” (CNIL, 2021, p. 37), providing a free and secure service in exchange for user data (Google Payments, n.d.).

The broader issue is the lack of regulatory oversight over big tech due to a sector-specific approach to regulation instead of a cross-sectoral one. The joint report of the European supervisory authorities20 highlights that big tech has a growing, albeit limited, role as direct financial service providers in Europe. At the same time, data protection authorities point out looming issues and call for a joint effort to address them across disciplines and borders (ESAs, 2024, p. 16 – 18). Various reports attempt to suggest different approaches to regulating big tech: while the Bank for International Settlements advocating “a comprehensive public policy approach that combines financial regulation, competition policy and data privacy“ (Crisanto et al., 2021, p. 12), James et al. (2024) plead for an International Digital Finance Network, potentially under the G7, or call on the EU to take the lead with a strong proposal if international-level initiatives are stalled.

PayPal operates as a closed-loop system, requiring both merchants and payers to hold accounts (Pozzolo, 2021, p. 36 – 37). Despite its convenience, similar data protection concerns arise, particularly due to the lack of a solid adequacy decision to rely on (Ferrari, 2020, p. 530). These concerns are amplified by the fact that PayPal may share personal data with third parties not only for payment processing but also for purposes such as marketing (PayPal, n.d.). Moreover, PayPal has announced plans to develop a marketing platform that would leverage user data for targeted advertising. In doing so, PayPal (2024) intends to “make merchants smarter to sell more products and services effectively” and enable “consumers to discover more of what they love.” Although these plans initially concern the US market, their successful implementation could extend to European market.

As digital wallet payments gain popularity, alternative solutions have to prove their viability as competitors. Solutions based on Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA)21 instant credit transfer (SCT Inst) with account-to-account payments already exist on the national level and are now emerging on the European level as well. They require the cooperation of multiple actors to function and reach a critical mass of customers necessary to leverage network effects. They are similar to Google and Apple Pay in terms of their mobile-based functionality but have entirely different underlying infrastructure. Well-known examples outside the euro area include Blik22 in Poland and Swish23 in Sweden, while the European Payment Initiative’s Wero wallet is currently being developed in the euro area as a pan-European solution.24

According to a payment expert, SCT Inst was created as an infrastructure for intra-European payments that do not rely on the Visa and Mastercard networks, thus ensuring that payments remain within Europe, under European law, and without data transfers abroad. The expert concluded that Wero is the European industry’s initiative to build on this infrastructure and that its account-to-account functionality gives it, by default, a data-minimizing setup. Similarly, the ECB’s digital euro project and accompanying legislation of the European institutions are currently underway. Maarten Daman, the ECB’s data protection officer, describes the project’s ambitions with respect to privacy as follows: “We will protect your payment data using a strong legal framework, technological innovation, and rigorous compliance. Ensuring state-of-the-art privacy and data protection is an essential part of the digital euro project” (Daman, 2024).

The ECB has demonstrated its commitment to ensuring the highest standards of privacy protection. The collaborative development of the rulebook with market participants, the availability of draft versions to the public,25 and the public negotiation of the design are indicative of dedication to enhancing transparency. Overall, Europe appears to be aware of the challenges ahead and is taking measures to address and mitigate the dominance of non-European actors.

3.7 Orbit Actors: The Use of Payment Data for Law Enforcement and Further Monetization

Edith’s payment data may also be used outside the payment processing chain. Orbit actors use payment data to build business models or fulfil their mandates. AISPs access and consolidate payment data when users grant their permission. In parallel, FIUs receive data from financial institutions due to AML and CFT guidelines. While AISPs operate within the framework of open banking with the aim of monetizing data, current regulations restrict them to payment accounts. However, legislative developments aim to broaden this scope within the open finance framework. Although data monetization has been the focus of this paper so far, enabling law enforcement is an integral part of the data governance trilemma (see Figure 1). As data volumes for monetization continue to grow, dual-use concerns arise. Enabling law enforcement with increasingly granular datasets for AML and CFT may raise alarms about data repurposing, potentially hindering privacy preservation efforts.

AISPs emerged with the implementation of the PSD2, which ended banks’ exclusive control over payment data (Westermeier, 2020, p. 2056 – 2058). Their role in the open banking framework allows customers to aggregate financial data from multiple institutions in apps like Finanzguru,26 typically through Application Programming Interface, so called APIs. Similar services exist in Europe, with regulatory frameworks fostering innovation but also presenting challenges in balancing economic potential with compliance constraints. Coche et al. (2024) highlight how discrepancies between regulations and their practical implementation may hinder AISPs’ efforts to comply with different regulations in different European countries. As open banking transitions towards open finance by extending data access to insurance, investment, or loans, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2023) has analyzed existing frameworks and discussed their impact on the financial market and customers. Furthermore, the European Commission (2024b) has proposed common European data spaces, including financial and health data, to standardize and regulate data-sharing frameworks across sectors.

The growing volume of payment data also raises concerns about dual-use issues. Data originally collected for commercial purposes may be repurposed for AML or CFT investigations. Financial institutions are required to submit suspicious transaction reports to national FIUs, which, in turn, collaborate with law enforcement agencies on the national and international levels (Lagerwaard et al., 2023). As Ferrari (2020) argues, the existing legal framework fails to address uncertainties about the repurposing of data, especially for data initially gathered for commercial purposes that may later serve investigative functions without this potential use being transparent to the user (p. 527). In the context of this study, an AML legal expert advocated for greater EU-wide harmonization of AML and GDPR requirements, particularly regarding data retention periods, because inconsistencies between the two frameworks generate non-compliance risks.

4 Findings: The Virtual Absence of Transparency Obscures What Payment Data Is Processed and How

The evolution of digital payments raises critical questions about the actors involved and how emerging payment data is used. The mapping of the payment landscape and the sequential analysis of the payment processing chain have shown that diverse constellations of actors influence the volume of data generated, with little transparency regarding what data is processed and how. Consequently, the ever-evolving and increasingly sophisticated strategies for monetizing data, as well as the growing capacity to enable law enforcement through access to more available granular data sets, are at odds with the claim of preserving privacy. This is especially because of the lack of transparency in data processing.

The research has demonstrated the critical role of contextual factors, such as where Edith chooses to make a purchase, with e-commerce and physical stores diverging markedly in terms of data intensity. Additionally, a merchant’s capacity to monetize data is closely linked to its data analytics capabilities and choice of PSP. Similarly, the bank a person selects influences how their data is used and also determines which card network is used to process their payments. At the same time and due to the regulatory environment the persistent issue of adequacy decisions with non-European countries remains a fundamental challenge within the European payment ecosystem.

Beyond the core architecture of the payment processing chain, mobile operating systems introduce further complexities, as the decision to buy a particular phone conditions the wallet solutions available to customers. Different business models have emerged in this respect, ranging from a focus on security at a certain cost for the bank to secure mobile payments in exchange for payment data. European privacy-preserving solutions offer an alternative, although their long-term market viability has yet to be determined.

Overall, the payment landscape is witnessing an expansion of data processing activities, particularly as the shift from open banking to open finance enables broader access to financial data beyond payment data. This expansion is furthered by the integration of other data spaces, raising new questions about data use on a larger scale.

Despite awareness of some issues, data use remains blurry, and the prevailing power of convenience does not incentivize transparency and as a consequence pave the way to preserving privacy. Payments will become more digital and interconnected, and the use of artificial intelligence, which may mean more opaque data processing, is not even part of the analysis. The Bank for International Settlements’ initiative to combine financial regulation, competition policy, and data privacy (see Crisanto et al., 2021, p. 12), the establishment of an International Digital Finance Network as a global forum, and the joint efforts of the European Supervisory Authorities are important steps that could strengthen privacy in payments in the medium term.

In addition, the development of a CBDC currently envisaged by the ECB as the digital euro, may be a particularly promising alternative. The ECB has demonstrated a consistent commitment to ensuring the highest standards of privacy protection; nonetheless, the outcome of the legislative procedure is not yet clear. Still, this commitment could influence other market participants to establish comparable standards, such as the EPI’s digital wallet Wero. The general approach of developing a rulebook for the digital euro with market participants and making the process transparent to the public marks a promising step towards greater transparency and may serve as a means to balance the data governance trilemma in favour of preserving privacy.

5 Conclusion

The payment landscape is witnessing the expansion of data processing activities, which fosters the objectives of monetizing data and enabling law enforcement. Meanwhile, new questions about the ever-worsening situation for data privacy become prevalent on a broader scale. Although the existence of a high volume of data is not inherently problematic, careful oversight and regulatory scrutiny are necessary to ensure responsible use. From a perspective of preserving privacy, the opacity and complexity of the payment processing chain make it difficult to determine the extent to which data is being used. The underlying purposes of data processing are often unclear, hindering transparency and accountability.

Looking ahead, monetizing data will become an increasingly integral aspect of payments and the financial sector as a whole. At the same time, the potential repurposing of payment data further blurs the distinction between the objectives of monetizing data and enabling law enforcement. Overall, the data governance trilemma is skewed toward these two objectives. Several efforts are being made to advance them, while complexity and lack of transparency prevent a conclusive assessment of the objective of preserving privacy. European privacy-preserving solutions offer an alternative and may help rebalance the data governance trilemma in favor of preserving privacy. Their long-term market viability, however, remains to be seen.

References

Abraham, R., Schneider, J., & vom Brocke, J. (2019). Data governance: A conceptual framework, structured review, and research agenda. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 424 – 438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.07.008.

Adyen. (2024). What is a payment service provider and how do they work? https://www.adyen.com/en_GB/knowledge-hub/what-is-a-payment-service-provider

Alrumiah, S., & Hadwan, M. (2021). Implementing big data analytics in e-commerce: Vendor and customer view. IEEE Access, 9, 37281 – 37286. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3063615

Auer, R., Böhme, R., Clark, J., & Demirag, D. (2025). Privacy-enhancing technologies for digital payments: mapping the landscape. Bank for International Settlements, Monetary and Economic Department. https://www.bis.org/publ/work1242.pdf

Barczentewicz, M. (2023). Schrems III: Gauging the validity of the GDPR adequacy decision for the United States (Issue Brief No. 2023-09-25). International Center for Law & Economics. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4585431

Bergemann, B. (2018). The consent paradox: Accounting for the prominent role of consent in data protection. In M. Hansen, E. Kosta, I. Nai-Fovino, & S. Fischer-Hübner (Eds.), Privacy and identity management: The smart revolution (pp. 111 – 131). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92925-5_8

Bigo, D., Isin, E., & Ruppert, E. (2019). Data politics: Worlds, subjects, rights. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315167305

Bindseil, U., & Pantelopoulos, G. (2023). Introduction to payments and financial market infrastructures. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-39520-8

Brandl, B., Hengsbach, D., & Moreno, G. (2024). Small money, large profits: how the cashless revolution aggravates social inequality. Socio-Economic Review, 23(2), 735 – 757. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwad071

Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin). (n.d.). Digital banking, neobanks and direct banks. https://www.bafin.de/EN/Aufsicht/FinTech/Geschaeftsmodelle/NeoBanks/NeoBanks_node_en.html

Colaps, A., & D’Cunha, C. (2023). “A clear imbalance between the data subject and the controller”: data protection and competition law. In Two decades of personal data protection. What next? EDPS 20th Anniversary. European Data Protection Supervisor. https://www.edps.europa.eu/system/files/2024-06/edps_20thanniversary-book_en.pdf

Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL) (2021). When Trust Pays Off - Today’s and tomorrow’s means of payment facing the challenge of data protection (White paper). https://www.cnil.fr/sites/cnil/files/atoms/files/cnil-white-paper_when-trust-pays-off.pdf

Crisanto, J. C., Ehrentraud, J., & Fabian, M. (2021). Big techs in finance: regulatory approaches and policy options. Financial Stability Institute, Bank for International Settlements. https://www.bis.org/fsi/fsibriefs12.pdf

Daman, M.G.A. (2024). Making the digital euro truly private. The ECB Blog. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/blog/date/2024/html/ecb.blog240613~47c255bdd4.en.html.

Doerr, S., Frost, J., Gambacorta, L., & Shreeti, V. (2023). Big techs in finance. Bank for International Settlements, Monetary and Economic Department. https://www.bis.org/publ/work1129.pdf

Dutch Banking Association (2019). The case for further reform of the EU’s AML framework. https://www.nvb.nl/media/3002/dutch-banking-association_the-case-for-further-reform-of-the-eus-aml-framework.pdf.

Ernst & Young. (2021). Why payments data is the key to unlocking new customer value. https://www.ey.com/en_gl/insights/banking-capital-markets/why-payments-data-is-the-key-to-unlocking-new-customer-value

European Central Bank (ECB). (2022). Study on the payment attitudes of consumers in the euro area (SPACE) – 2022. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/ecb_surveys/space/shared/pdf/ecb.spacereport202212~783ffdf46e.en.pdf

European Central Bank (ECB). (n.d.). Single euro payments area (SEPA). https://www.ecb.europa.eu/paym/integration/retail/sepa/html/index.en.html

European Commission. (2024). Adequacy decisions: How the EU determines if a non-EU country has an adequate level of data protection. https://commission.europa.eu/law/law-topic/data-protection/international-dimension-data-protection/adequacy-decisions_en.

European Commission. (2024a). Data Protection: European Commission adopts new adequacy decision for safe and trusted EU–US data flows. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_3721.

European Commission. (2024b). Commission staff working document on common European data spaces. https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/redirection/document/83562

European Data Protection Board (EDPB). (2024). Safeguarding individual’s rights – EDPB annual report 2023. https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2024-04/edpb_annual_report_2023_en.pdf

European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) & Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEPD). (2021). 10 Misunderstandings related to anonymisation. https://www.edps.europa.eu/system/files/2021-04/21-04-27_aepd-edps_anonymisation_en_5.pdf

European Parliament. (2020). The CJEU judgment in the Schrems II case. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2020/652073/EPRS_ATA(2020)652073_EN.pdf

Ferrari, V. (2020). Crosshatching privacy: Financial intermediaries’ data practices between law enforcement and data economy. European Data Protection Law Review, 6(4), 522-535. https://doi.org/10.21552/edpl/2020/4/8

Ferrari, V. (2023). Money after money: Disassembling value/information infrastructures [Doctoral dissertation, University of Amsterdam]. https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=30904422-2233-4400-bc5f-e7971b33f758

Google Payments. (n.d.). Google payments privacy notice. https://payments.google.com/payments/apis-secure/get_legal_document?ldo=0&ldt=privacynotice

James, S., & Quaglia, L. (2024). Bigtech finance, the EU’s growth model and global challenges. European Parliament, Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2024/755724/IPOL_IDA(2024)755724_EN.pdf.

Kondor, D., Hashemian, B., de Montjoye, Y.-A., & Ratti, C. (2020). Towards Matching User Mobility Traces in Large-Scale Datasets. IEEE Transactions on Big Data, 6(4), 714 – 726. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBDATA.2018.2871693

Lagerwaard, P. (2018). Following suspicious transactions in Europe: Comparing the operations of European financial intelligence units (FIUs). Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research at the University of Amsterdam. https://hdl.handle.net/11245.1/a708f9a6-6437-482f-969e-b9e119fbec8e

Lagerwaard, P., & de Goede, M. (2023). In trust we share: The politics of financial intelligence sharing. Economy and Society, 52(2), 202 – 226. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2023.2175451

Leibbrandt, G., & Teran, N. D. (2021). The pay off: How changing the way we pay changes everything. Elliott & Thompson.

Makhlouf, G. (2023, November 11). The changing landscape for financial services [Paper presentation]. Irish League Credit Unions Conference, Dublin, Ireland. https://www.bis.org/review/r231113t.htm.

Mastercard. (2018, October 10). Contactless payments at cash register with Google Pay and Mastercard now also for German PayPal customers [Press release]. https://www.mastercard.com/news/europe/en/newsroom/press-releases/en/2018/october/contactless-payments-at-cash-register-with-google-pay-and-mastercard-now-also-for-german-paypal-customers/

Mastercard. (n.d.). Global privacy notice. https://www.mastercard.us/en-us/vision/corp-responsibility/commitment-to-privacy/privacy.html

Mützel, S., & Unternährer, M. (2024). Digital payments and relational embedding: Turning relations into data and data into relations. Big Data & Society, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517241266432

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). Personal data use in financial services and the role of financial education: A consumer-centric analysis. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/06998d33-en

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2023). Shifting from open banking to open finance: Results from the 2022 OECD survey on data sharing frameworks. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9f881c0c-en

Panetta, F. (2022, March 30). A digital euro that serves the needs of the public: striking the right balance [Official statement]. Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs of the European Parliament. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2022/html/ecb.sp220330_1~f9fa9a6137.en.html

Payment Systems Regulator. (2018). Data in the payments industry. https://www.psr.org.uk/media/rscd3p2e/psr-discussion-paper-data-in-the-payments-industry-june-2018.pdf

PayPal. (2024, May 28). PayPal announces new leaders to build new advertising platform and accelerate consumer product innovation [Press release]. https://newsroom.paypal-corp.com/2024-05-28-PayPal-Announces-New-Leaders-to-Build-New-Advertising-Platform-and-Accelerate-Consumer-Product-Innovation

PayPal. (2025, August 18). Driving European competitiveness with digital payments [Press release]. https://newsroom.paypal-corp.com/2025-08-driving-european-competitiveness-with-digital-payments

PayPal. (n.d.) List of third Parties (other than PayPal customers) with whom personal information may be shared. https://www.paypal.com/de/legalhub/paypal/third-parties-list?locale.x=en_US

Poell, T., Nieborg, D., & Van Dijck, J. (2019). Platformisation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1425

Pozzolo, A. F. (2021). PSD2 and the transformation of the business model of payment services providers. In E. Bani, V. De Stasio, & A. Sciarrone Alibrandi (2021). The transposition of PSD2 and open banking (pp. 27 – 42). Bergamo University Press.

Rajamannar, R. (2023). The Mastercard Digital EngineTM: Using AI to spot micro trends for effective customer engagement. Management and Business Review, 3(1 – 2), 15 – 18. https://doi.org/10.1177/2694105820230301003.

Revolut. (n.d.). Customer privacy notice. https://cdn.revolut.com/terms_and_conditions/pdf/customer_privacy_notice_52996afd_0.3.0_1737476300_en.pdf

Statcounter. (2025). Mobile operating system market share Europe (Jan 2024–Jan 2025). Statcounter – Global Stats. https://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-share/mobile/europe.

Stripe. (2023). Online payment processing 101: What businesses need to know. https://stripe.com/en-de/resources/more/online-payment-processing-101#5-issuing-bank-or-card-network

Stripe. (2023a). Payment tokenisation – the basics: What it is and how it benefits businesses. https://stripe.com/ie/resources/more/payment-tokenization-101

Stripe. (n.d.). A guide to unified commerce. https://stripe.com/en-de/guides/unified-commerce-guide#5-personalise-the-shopping-experience

Temelkov, Z. (2020). Differences between traditional bank model and fintech based digital bank and neobanks models. SocioBrains, 74, 8 – 15. https://eprints.ugd.edu.mk/27605/1/2._Zoran_Temelkov.pdf

Uhlig, H., Alonso, M., & Frost, J. (2023). Privacy in digital payments: Escaping the panopticon. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 24(2), 174 – 180. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/gia.2023.a913643

Visa Consulting & Analytics. (2020). Digital targeting and acquisitions in the new normal. https://corporate.visa.com/content/dam/VCOM/global/services/documents/digital-targeting-and-acquisitions-in-the-new-normal.pdf

Visa South East Europe. (n.d.). Gain competitive edge with payments data and analytics. https://www.visasoutheasteurope.com/partner-with-us/visa-analytics-platform.html#5d682dc08a

Visa. (n.d.). Visa global privacy notice. https://usa.visa.com/legal/global-privacy-notice.html

von Grafenstein, M. (2022). Reconciling conflicting interests in data through data governance. An analytical framework (and a brief discussion of the Data Governance Act Draft, the Data Act Draft, the AI Regulation Draft, as well as the GDPR). HIIG Discussion Paper Series, 2022(2). https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4104502

von Grafenstein, M., Kiefaber, I., Heumüller, J., Rupp, V., Graßl, P., Kolless, O., & Puzst, Z. (2024). Privacy icons as a component of effective transparency and controls under the GDPR: effective data protection by design based on art. 25 GDPR. Computer Law & Security Review, 52, Article 105924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2023.105924

Weber, S., & Wallraf, A. (2023). Harvesting payment data for fiscal purposes: The EU’s Central Electronic System of Payment information. Journal of Payments Strategy & Systems, 17(4), 372 – 380. https://doi.org/10.69554/RNYY8485

Wero. (n.d.). About. https://wero-wallet.eu/about

Westermeier, C. (2020). Money is data – The platformization of financial transactions. Information, Communication & Society, 23(14), 2047–2063. http://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1770833

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for the future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs.

Zygmuntowski, J. O. (2023). Data governance in a trilemma: A qualitative analysis of rights, values, and goals in building data commons. Digital Society, 2(2), Article 30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44206-023-00058-y

Date received: 19 March 2025

Date accepted: 10 November 2025

1 Digital payments at the point of sale include card payments and mobile payments, which are typically made through a digital wallet application.

2 Meanwhile, POS transactions in terms of value rose from 44% in 2019 to 50% in 2022 (ECB, 2022, p. 12 – 13).

3 This clear trend does not even take into account the fact that online purchases account for a growing share of consumption.

4 Companies like Adyen or Stripe usually offer all-in-one solutions, called full-stack PSP.

5 The initiative is accompanied by the digital euro package put forward by the European Commission, which is currently being negotiated by the European parliament and the Council of the European Union.

6 Eight interviews were conducted with experts in different fields relevant to the research topic: three privacy officials, a commercial bank employee, a journalist specialised in payments, a payment expert, a legal expert in anti-money laundering (AML) and counter financing terrorism (CFT), and a legal expert in privacy and payments. The basic set of questions remained the same for all interviews, but the general openness of semi-structured interviews enabled the researcher to adjust questions and allowed interviewees to introduce new aspects. The intricacies of the field of payments are challenging to comprehend due to the paucity of comprehensive and readily available literature. This exploratory approach produced the insights presented and analysed within the framework of the data governance trilemma (Zygmuntowski, 2023).

7 In particular through a structured, topic-centric literature review of peer-reviewed scientific literature, as well as select practitioner publications. The review covered 145 works, including peer-reviewed papers, seminal books, publications from inter-governmental organizations (e.g., Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), industry associations (e.g., International Organization for Standardization), and corporate organizations (e.g., IBM).

8 Directive (EU) 2016/680 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data by competent authorities for the purposes of the prevention, investigation, detection or prosecution of criminal offences or the execution of criminal penalties, and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Council Framework Decision 2008/977/JHA.

9 Directive (EU) 2015/2366 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2015 on payment services in the internal market, amending Directives 2002/65/EC, 2009/110/EC and 2013/36/EU and Regulation (EU) No 1093/2010, and repealing Directive 2007/64/EC.

10 See Art. 4(16) and (19) PSD2.

11 However, obfuscation may still be possible because payments can also be made on behalf of others, for instance, in a shared household or for children.

12 These purposes were noted during a comparative review of the documents and illustrate the diverse ways data is used.

13 Notable examples include Amazon Pay on a global scale or Otto Payments in Germany.

14 This includes adhering to industry standards like the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards or regulatory requirements such as the PSD2.

15 The CLOUD Act allows US law enforcement bodies to access data stored by US-based technology companies, independent of where the data is located, i.e. accessing data located for instance in the European Union.

16 Because the focus of the research is on customers’ payment data, the acquiring bank is not a fundamental part of the analysis.

17 Instead of using and storing sensitive card information, they use payment tokenization technology, which converts sensitive data into a secure, non-sensitive alternative (see Stripe, 2023a).

18 With one exception: in 2018, PayPal began offering German customers a Mastercard that can be stored in the Google Pay wallet application (see Mastercard, 2018), as well as NFC payments on the PayPal app (see PayPal, 2025).

19 Web presence: https://wero-wallet.eu/

20 Namely, the European Banking Authority, the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority, and the European Securities and Markets Authority.

21 Launched in 2008 and fully implemented by 2014 (ECB, n.d.), SEPA harmonizes cashless euro payments in 38 European countries, enabling seamless euro transactions across borders.

22 Web presence: https://blik.com/en

23 Web presence: https://www.swish.nu/

24 The launch markets are Belgium, France, and Germany, and EPI plans to make its wallet available throughout Europe (Wero, n.d.).

25 Version 0.9 can be found at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/euro/digital_euro/timeline/profuse/shared/pdf/ecb.derdgp250731_Draft_digital_euro_scheme_rulebook_v0.9.en.pdf

26 A German financial management app that consolidates account data from the user’s bank accounts to provide them with a comprehensive financial overview as well as additional offerings for seemingly better deals, for instance, from insurance or energy suppliers. Web presence: https://finanzguru.de/

Metrics

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Marek Jessen (Author)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.