Disconnecting in a Digital World

A Practice-based Approach

1 Introduction

Until relatively recently, being unreachable – being digitally disconnected – was the default. In the early days of the internet, going online was a deliberate act. It meant sitting at a desk in front of a computer, actively connecting to the World Wide Web. Today, we are not just connected but immersed and fused with mobile digital technologies (El Sawy, 2003). Smartphones slip in and out of our pockets, delivering notifications from friends, acquaintances, and countless apps; smartwatches rest on our wrists, reminding us to take 10,000 steps a day; and voice assistants await our commands on kitchen counters, ready to set timers, play music, or report the weather. Whether ordering an Uber, swiping through potential partners, or discovering new music, practices of everyday social life are increasingly mediated by technology. This deep mediazation (Hepp, 2020) contributes to the perception of “being permanently online, permanently connected” (Vorderer et al., 2017).

Living in an “always-on” society (Nguyen, 2021) has raised growing concerns about its effects on well-being. For instance, constant connectivity is associated with diminished autonomy due to blurred boundaries between work and personal life (Mazmanian et al., 2013) and reduced well-being (Büchler et al., 2020). In response, the concept of digital well-being has gained traction across disciplines (cf. Vanden Abeele & Nguyen, 2022). With a focus on investigating the relationship between digital technology use and human flourishing, the concept articulates what it means to live well in a digital world (Burr & Floridi, 2020).

A central theme in both academic and public discourse on digital well-being is digital disconnection, understood as a purposeful and time-limited withdrawal from digital media, devices, or features to support well-being (Nassen et al., 2023). Scholars have framed voluntary disconnection as a response to digital saturation (Natale & Treré, 2020) and as a strategy to restore and improve emotional, psychological, and social well-being (Morrison & Gomez, 2014; Nguyen, 2021, 2023; Nassen et al., 2023; Klingelhoefer et al., 2024; Vanden Abeele et al., 2024). Typical disconnective strategies include behavioral approaches, such as scheduling offline time, as well as feature-based interventions, such as muting notifications or deleting apps (Nguyen et al., 2022). While these approaches offer practical interventions (Lyngs et al., 2019; Vanden Abeele et al., 2024), they often foreground agency and intentionality.

However, this is not to say that disconnection is always planned or deliberate. People can find themselves disconnected because a face-to-face conversation becomes more engaging than watching reels, or they accidentally leave their phone in another room. These situational, unplanned occurrences often go unnoticed in the literature. In this paper, we turn our attention to such emergent disconnective practices that unfold in the flow of everyday life.

A second concern in the literature is the tendency to frame disconnection in binary terms: people are either “on” or “off” a platform, device, or app (Nguyen, 2021; Marx et al., 2024, p. 24). However, lived experience suggests a more fluid continuum. Someone might mute social media notifications but still mentally anticipate messages. Can that be considered disconnection?

From an information systems (IS) research perspective, we foreground the sociotechnical nature of digital disconnection (Sarker et al., 2019). Specifically, we adopt the theoretical lens of practice theory, a sociological school of thought that addresses sociotechnical phenomena through how people engage with certain technologies in the course of their daily lives (Orlikowski, 1996; Reckwitz, 2002; Oborn et al., 2011; Barrett et al., 2012). According to practice theory, any phenomenon related to technology is not only a question of its design and engineering, but a question of it interacting with people in routinised practices (Feldman & Orlikowski, 2011; Whittington, 2011).

Drawing on practice theory, we explore how disconnective practices unfold over time, shaped by emotional and cognitive states, tools and objects, technical configurations, and spatial context. This approach captures the everyday complexities of how individuals engage with and disengage from digital technologies, as well as the implications for their well-being. We pose the following research question: How is digital disconnecting from mobile devices enacted in practice by individuals in everyday life?

Our paper makes two conceptual contributions to research on digital disconnection and digital well-being. First, we present a practice-based understanding of digital disconnection by introducing the term digital disconnecting. This foregrounds how disconnecting unfolds contextually and continuously over time, and does not always result from conscious intent. Drawing on 12 interviews and 5 observations, we show how individuals engage in disconnecting through actions that may be planned, habitual, or incidental. Digital disconnecting productively complements the more agentic and strategic concept of deliberately employing “disconnection strategies” (Bossio & Holton, 2021; Nguyen, 2021; Vanden Abeele et al., 2024) by offering a language and lens suitable for those situations where it is hard to draw an exact line between individuals’ strategic intentions and the digital world they must navigate.

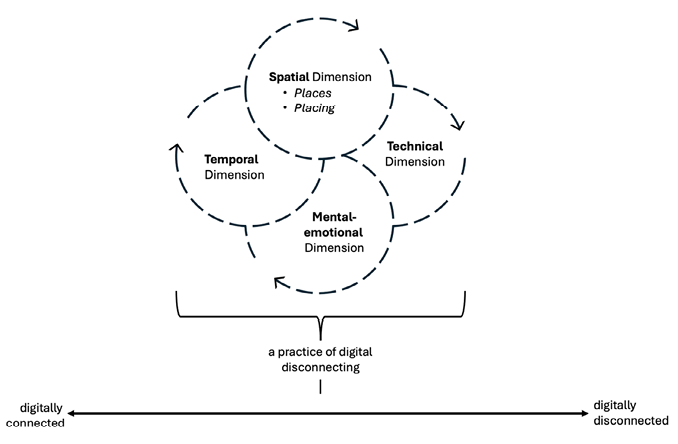

Second, we identify and theorize the role of spatiality in digital disconnecting. Through four coding rounds of our empirical material, we found that participants’ ability to disconnect varied depending on their spatial context; that is, the places they were at and the placing of their digital devices. Our findings suggest that this shapes how other dimensions of disconnecting – temporal, mental-emotional, and technical – are configured in everyday practice. We thus propose spatiality as a distinct analytical dimension of digital disconnecting.

This paper is structured as follows: We begin with the conceptual background, followed by the research method. We then report our findings and conclude by discussing their implications, limitations, and directions for further research.

2 Conceptual Background

In this section, we review the literature informing our development of a practice-based approach to digital disconnection. We begin by situating digital disconnection within the context of digital well-being, before turning to a practice-theoretical perspective that foregrounds the interaction and fusion of interrelated dimensions.

2.1 A Brief Introduction to Digital Disconnection

Digital disconnection is a key topic related to research on digital well-being (e.g., Vanden Abeele, 2020; Jorge et al., 2022; Nguyen et al., 2022; Vanden Abeele & Nguyen, 2022). Voluntary digital disconnection has commonly been framed as a means to restore or enhance productivity, attention, a sense of control, privacy, health, social relationships, and overall well-being (see Morrison & Gomez, 2014; Nguyen, 2021, 2023; Nassen et al., 2023; Klingelhoefer et al., 2024; Vanden Abeele et al., 2024). It has been considered as “an antidote to an increasing saturation with digital technologies” (Natale & Treré, 2020, p. 626), “[a] much-discussed solution for undesirable (over-)use of mobile technologies” (Klingelhoefer et al., 2024, p. 1), and a “necessary act of care” to foster well-being (Van Bruyssel et al., 2023). Vanden Abeele (2020) defined digital well-being as “an experiential state of optimal balance between connectivity and dysconnectivity” (Vanden Abeele, 2020, p. 932). The underlying assumption is that digital disconnection strategies help limit digital connectivity, and thus potential or perceived overuse, in order to restore balance, which, in turn, supports overall well-being, particularly digital well-being (Vanden Abeele et al., 2024).

We focus on voluntary digital disconnection, drawing on Nassen et al.’s (2023) definition of it as “a deliberate form of non-use of devices, platforms, features, interactions and/or messages that varies in frequency and duration with the aim of restoring or improving one’s perceived overuse, social interactions, psychological well-being, productivity, privacy and/or perceived usefulness” (p. 1).

Foregrounding deliberation, this definition frames digital disconnection as a reflexive, self-conscious act. Schatzki (2025) distinguished between different forms of acting: intentional acting (aiming to act), purposeful acting (acting in order to achieve something), and self-conscious acting (being aware that one is acting and aiming to act). While intention and purpose need not be consciously held, self-conscious acting necessarily involves such cognitive activities as deliberation, reflection, and planning – in short, reflexivity. While this emphasis on deliberate, and thus self-conscious, action aligns with much of the literature on disconnection strategies, it risks overlooking the extent to which disconnective practices may also emerge incidentally or without self-conscious deliberation, reflection, and planning (a point we will return to later).

The definition also states what individuals “do not use” or disconnect from, namely “devices, platforms, features, interactions and/or messages” (Nassen et al., 2023, p. 1). Nguyen (2021) proposed a typology of disconnection strategies that includes disconnecting from devices, from specific platforms/apps, and from platform/app content, communication, and features. In contrast, related research on digital detoxing suggests that individuals disconnect from devices, applications/tools, and digital/social media (Marx et al., 2024). To further conceptualize and differentiate the levels at which disconnection can occur, we draw on the Hierarchical Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) Taxonomy by Meier & Reinecke (2021). This framework distinguishes between two overarching conceptual research approaches: the channel-centered approach and the communication-centered approach. The former focuses on the medium itself and identifies four analytical levels: (1) the device (e.g., smartphone, laptop), (2) the type of application (e.g., social media, email), (3), branded applications (e.g., TikTok, Instagram), and (4) specific features (e.g., status updates, reels, notifications). This perspective largely treats communication content as a black box. In contrast, the communication-centered approach shifts the focus from the technical channel to communication as a dynamic and complex social process. Here, the analytical focus lies on: (5) interactions (e.g., degree of user engagement or the directionality of interaction) and (6) messages (e.g., their mode, content, accessibility). A more detailed discussion of the technical aspects of disconnection follows below.

Individuals also determine the “frequency and duration” of their disconnection (Nassen et al., 2023, p. 1); for instance, temporarily (Jorge, 2019; Marx et al., 2024) or more permanently (Šimunjak, 2023, p. 10). Typically, users disconnect to reconnect eventually. We return to the temporality of disconnection in the next section.

Digital disconnection aims to restore or improve such well-being-related aspects as perceived overuse, attention, privacy, and productivity (Nassen et al., 2023, p. 1; see also Morrison & Gomez, 2014; Vanden Abeele, 2020; Nguyen, 2021, 2023; Klingelhoefer et al., 2024). Yet, disconnection, in itself, does not necessarily lead to these outcomes (Radtke et al., 2022; Nguyen & Hargittai, 2023; Vanden Abeele et al., 2024). Returning to Vanden Abeele’s (2020) definition, digital well-being is a matter of dynamic balance between connectivity and dysconnectivity, rather than mere non-use. Accordingly, whether disconnective practices enhance well-being is contingent upon the interplay of different elements, such as device configurations, affective states, and contextual aspects (Vanden Abeele, 2020).

2.2 Toward Understanding Digital Disconnection as a Continuum of Interrelated Dimensions

IS research holds important implications for conceptualizing digital disconnection, as the phenomenon is inherently sociotechnical and the field’s central concern is sociotechnical phenomena (Sarker et al., 2019). El Sawy (2003) outlined three different perspectives through which IS addresses these phenomena: The connection view conceptualizes information technology (IT) as a tool that is conceptually separate from people, requiring them to actively choose whether or not to connect (see Orlikowski & Iacono, 2001; El Sawy, 2003). The immersion view suggests that technology is integrated into social relations through ubiquitous network connectivity, potentially rendering a complete disconnection of humans from technology challenging (Orlikowski & Scott, 2008). Finally, the fused view casts technology as conceptually inseparable from individuals’ professional activities and personal lives (Orlikowski & Scott, 2008; Yoo, 2010).

While these three perspectives have been developed primarily in organizational research (e.g., El Sawy, 2003; Orlikowski & Scott, 2008), we draw on them here to frame sociotechnical entanglements in everyday life more broadly. Nonetheless, work and organizational contexts can significantly shape individuals’ digital disconnection practices. For example, the use of mobile messaging platforms, such as WhatsApp, for both professional and personal communication can blur boundaries between work and leisure, which can complicate efforts to disconnect and give rise to distinct strategies (Mols & Pridmore, 2021). Organizational norms and technological infrastructures may thus structure when and how individuals are expected to be reachable, and how easily they can disengage, which has been shown to diminish one’s sense of autonomy (Mazmanian et al., 2013) and well-being (Büchler et al., 2020).

These three perspectives are particularly useful for conceptualizing digital disconnection because they illuminate different ways of theorizing the human–technology dynamic, each of which foregrounds distinct sociotechnical dynamics that can shape disconnective practices. Much research on voluntary digital disconnection has foregrounded individuals’ agency to deliberately connect and disconnect (see Nassen et al., 2023), implying a conceptual understanding of digital disconnection as a binary state: being either connected (i.e., online, engaged, or simply reachable) or disconnected (i.e., offline, disengaged, or unreachable). This perspective aligns closely with the connection view (El Sawy, 2003).

However, recent IS research has suggested that the immersion and fusion views have gained increasing relevance, as they more accurately reflect our embodied experiences with mobile digital technologies (see Yoo, 2010; Yoo et al., 2024). For instance, Baskerville et al. (2019) highlighted an “ontological reversal,” where the digital world significantly shapes the physical. Which Uber driver we might hire in an unknown city, for example, is managed by algorithms, along with pricing and pick-up times (Möhlmann et al., 2021) – all of which require constant connectivity (El Sawy, 2003). Furthermore, Yoo (2010) emphasized that our everyday lives are deeply entwined with technology, consequently shaping how we experience the world (Lorenz et al., 2024). These conceptual insights are echoed in the notion of a “deep mediatization” of life (Hepp, 2020), entailing “24/7 connectivity” (Vanden Abeele & Nguyen, 2022; Vanden Abeele et al., 2022) and being “permanently online, permanently connected” (Vorderer et al., 2017) in an “always-on” society (Nguyen, 2021). Smartphones have come to be perceived as extensions of ourselves (Park & Kaye, 2019), with various researchers arguing that the vast majority of us are “tethered” to our digital devices to varying degrees (Turkle, 2008; Mihailidis, 2014; Bucher, 2020).

These considerations raise important questions about how digital disconnection is conceptualized. One issue is whether and how a binary distinction between being either connected or disconnected can be further developed. While it may be useful to frame digital disconnection as a binary in certain contexts, such as distinguishing between work and private spheres, our private lives have become increasingly immersed in and fused with digital technologies. This blurs the boundary between “online” and “offline.”

This example points to a broader conceptual challenge: determining precisely when an individual is considered disconnected, which raises a number of questions. For example, does it qualify as disconnection when individuals refrain from glancing at their phones while mentally anticipating notifications? Are people disconnected when they log out of their social media accounts, or does disconnection require full deletion? To what extent can someone be considered disconnected if they carry a smartphone in their pocket, even when it is turned off? In short, what does it mean to be “disconnected” in empirical practice?

One implication of the abovementioned considerations is that it may be helpful to conceptualize digital disconnection as a continuum, wherein the blurring of “connected” and “disconnected” is not a limitation, but a constitutive characteristic of how digital disconnection can be conceptually understood. In this context, the fused view of IS phenomena (El Sawy, 2003) is particularly useful, as it enables us to build on prior research that has investigated various aspects of digital disconnection, such as its temporal (Jorge, 2019; Radtke et al., 2022; Farooq et al., 2023; Šimunjak, 2023; Marx et al., 2024), mental-emotional (e.g., Park & Kaye, 2019; Cai et al., 2020; Gerlach & Cenfetelli, 2020; Vanden Abeele & Nguyen, 2023), and technical aspects (e.g., Lyngs et al., 2019; Meier & Reinecke, 2021; Nguyen, 2021). We conceptualize these aspects as interrelated dimensions that dynamically fuse in empirical practice.

A temporal dimension is inherent in the above-cited definition, as digital disconnection refers to non-use “that varies in frequency and duration” (Nassen et al., 2023, p. 1). Temporary disconnection can involve individuals interrupting ongoing use (i.e., taking a break), imposing usage constraints (i.e., setting a time limit), or defining a clear start and end point for disconnecting (i.e., a disconnection period; Marx et al., 2024). At the other end of this temporal continuum lie more permanent forms of digital disconnection, such as deleting apps or social media accounts (Šimunjak, 2023). More enduring practices are reflected in related concepts, such as social media discontinuation (Farooq et al., 2023) and mobile phone refusal (Rosenberg & Vogelman-Natan, 2022).

The mental-emotional dimension has also been acknowledged in extant research. The aim of digital disconnection is mitigating “perceived overuse” and enhancing “social interactions, psychological well-being, productivity, privacy and/or perceived usefulness” (Nassen et al., 2023, p. 1). This suggests that digital disconnection is not only about (not) using a device but also involves how individuals are cognitively and affectively relating to a device and to the practices of connecting, disconnecting, and reconnecting (Park & Kaye, 2019; Cai et al., 2020; Vanden Abeele & Nguyen, 2023). Emotional and cognitive states can complicate disconnection efforts. For example, the perceived need to stay up to date may lead to constant checking behaviors (Gerlach & Cenfetelli, 2020). While setting screen-time limits may result in temporal non-use, such practices can provoke emotional distress (e.g., fear of missing out), raising questions about what constitutes genuine disconnection. In contrast, going for a hike while carrying a smartphone solely for emergencies, but without checking it once, may represent a meaningful mental-emotional form of disconnection, despite ongoing technical connectivity.

Digital disconnection inherently involves a technical dimension, as individuals make decisions about what exactly to disconnect from – devices, platforms, features, interactions, and/or messages (cf. Meier & Reinecke, 2021; Nguyen, 2021; Nassen et al., 2023; Marx et al., 2024; see the above discussion). These levels, as conceptualized in the Hierarchical CMC Taxonomy, are conceptually distinct, yet often fused in practice. For instance, given that social media use constitutes a large part of mobile digital technology use (Villanti et al., 2017), disconnecting from a platform may simultaneously entail disconnecting from the device. In their experience sampling study, Klingelhoefer et al. (2024) empirically examined 7,360 instances of disconnective behavior among 230 young adults. Their analysis reveals that disconnection was frequently not confined to a single level but instead often overlapped, occurring in 36% of cases at the device level, 46% at the application level, 48% at the feature level, 51% at the interaction level, and 52% at the content level. These findings underscore the layered and overlapping nature of everyday disconnective practices, highlighting that disconnection is rarely a singular or isolated act, but rather a multi-level practice.

Individuals may put their phones aside and temporarily disconnect from selected devices, platforms, features, interactions, and/or messages of their choice. Technically, however, their email accounts, social media profiles, and phone numbers continue to exist and leave associated digital traces. Even while not actively engaging, individuals remain contactable and may be subject to data extraction, which is central to generating customer value for many firms (Yoo et al., 2010; Gregory et al., 2020; Yoo et al., 2024). Even screen-time monitoring apps, marketed as a way to support disconnection, contribute to persistent connectivity: Users may refrain from interacting with their devices and specific applications, yet data collection continues (Jorge et al., 2022). In this context, Bucher (2020) provocatively argued that there is “nothing to disconnect from,” suggesting that full disconnection is, in effect, an illusion due to our constant connection. This view resonates with the fusion perspective, wherein digital technology and humans are increasingly entangled (El Sawy, 2003).

In sum, this section aimed to show that the temporal, mental-emotional, and technical dimensions of digital disconnection fuse in practice, and that this fusion supports conceptualizing digital disconnection as a continuum.

2.3 Approaching the Relations between Different Dimensions of Digital Disconnection from a Practice Lens

To support this conceptualization, we draw on insights from practice theory from sociology. This perspective helps to understand how disconnection plays out in the concrete activities of everyday life. Practice theory attends to the daily doings of people (Feldman & Orlikowski, 2011; Whittington, 2011), offering a lens through which to understand how digital technologies become consequential in daily experience (Yoo, 2010; Vaast & Pinsonneault, 2022). From this viewpoint, digital disconnection can be conceptualized as a practice shaped by the dynamic fusing of the abovementioned dimensions in the concrete activities of individuals. We adopt Reckwitz’s (2002) definition of practices as “a routinized type of behavior which consists of several elements, interconnected to one another: forms of bodily activities, forms of mental activities, ‘things’ and their use, a background knowledge in the form of understanding, know-how, states of emotion and motivational knowledge” (p. 249). There are, arguably, many different definitions of practices in the literature, some attached to significant philosophical underpinnings (Feldman & Orlikowski, 2011; Whittington, 2011; Kautz & Jensen, 2013; Hultin, 2019). A discussion of these far-reaching implications for ontology and epistemology is beyond the scope of our paper, and we particularly adopt Reckwitz’s (2002) definition of practices given its use in IS research to explore individuals’ mental and emotional engagements with digital technology (Wessel et al., 2019; Wessel et al., 2024).

A practice theory approach highlights that things, such as digital technologies, and their use unfold over time (Orlikowski, 1996; Feldman & Orlikowski, 2011; Orlikowski & Scott, 2015). For example, in their study on the use of electronic patient records, Oborn et al. (2011) showed that these records are not isolated tools; rather, their value emerges through situated practices – that is, through doctors’ routine practices, such as discussing, updating, and interpreting patient data in the records. Thereby, the records unfolded only through hospital staff interacting with them over time (see also Lebovitz et al., 2022). This perspective also applies to everyday practices, such as constantly checking mobile devices (Gerlach & Cenfetelli, 2020), relying on smart locating systems to support people with dementia and their caregivers (Wessel et al., 2019), or engaging with artifacts designed for chronic care (Bardhan et al., 2020; Wessel et al., 2024). Similarly, how people engage with or disengage from digital technologies is a continuous and evolving practice.

This section has expanded on our earlier discussion of the dimensions of digital disconnection by grounding the idea of their dynamic, situated fusion in a guiding theoretical framework. We drew on sociological practice theory as this lens allowed us to capture how the dimensions of digital disconnection come together in practice.

3 Methods, Data Collection, and Data Analysis

Our study aims at theoretical generalization (Lee & Baskerville, 2003, 2012), specifically by developing a practice-based understanding of digital disconnection to capture how different dimensions of disconnecting fuse within the concrete, daily activities of individuals. We employed qualitative methods for this purpose, as these are well-suited to developing novel conceptual insights that future research can further explore (Bansal & Corley, 2011).

3.1 Data Collection: Interviews and Observations

We conducted interviews with 12 individuals and shadowed 5 of them (from between a half to a full day). The participants were purposefully sampled (Knott et al., 2022) from within our personal networks. Our goal was to include individuals with varying relationships to their mobile device use, ranging from reporting only minor annoyances (e.g., Luca and Niklas, who mentioned being disturbed by group messages or the phone lighting up without cause) to those describing significant struggles (e.g., Oliver, who referred to his extended periods (weeks and months) of high screen time as “long-term misery” (Oliver, personal communication, December 2022)). Participants were required to own and use a smartphone in their everyday life and be open to discussing their usage practices. Data collection was concluded after 12 interviews and 5 observations, as we began to observe how disconnective practices unfolded and felt confident in our ability to conceptualize them meaningfully.

The interviews were conducted between December 2022 and March 2023, during the COVID-19 pandemic. While no lockdown measures were in place, some interviews were held via video call for practical reasons. The interviews were guided by a broad, open-ended prompt: “Tell me about you and your phone. What do you enjoy and what do you dislike?” This allowed the participants to shape the conversation based on what they found meaningful. The interviewer (one of the authors) asked follow-up questions tailored to the participants’ responses to explore their experiences in more depth. This flexible format aligned with our practice-based lens, which foregrounded lived experiences and the situated nature of action. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Pseudonyms were used throughout, and an overview of the collected data and study participants is provided in Table 1 below. The interview lengths ranged from 25 minutes to 3.5 hours, reflecting differences in participants’ availability and depth of engagement. Such variation is common in qualitative research and reflects our flexible, participant-centered approach. For instance, the interview with Oliver unfolded as a narrative of his evolving relationship with digital technologies. To protect participant anonymity, given our convenience-based recruitment through personal networks, we include an aggregated summary of participant characteristics here: Participants were aged between 21 and 34 years. Most participants were living in Germany or Spain, except for two residing in South Korea. Seven participants were from Germany, and one each from Spain, the United Kingdom, Iran, Ukraine, and the United States.

Five participants were also shadowed by one researcher for a period ranging from half a day to a full day, with their explicit consent. These participants were recruited based on their willingness to be shadowed. While this introduced some practical constraints, we aimed for variation across age and gender within our sample. The shadowing took place in the participants’ everyday settings, including commutes, workplaces, and leisure environments. For example, Tabea was shadowed after work, during her commute home and while relaxing at home. Luca was shadowed at home on a day off, and Niklas was shadowed after work during his commute, a yoga class, and at home. Simon’s shadowing included working hours, a gym session, and leisure time, and Leonie was observed during a full university day, consisting of time at university and at home. Throughout the observations, the researcher took detailed field notes, capturing both relevant and seemingly unrelated activities, as well as near-verbatim participant quotes. Photographs of participants’ environments were taken selectively, with participants’ explicit consent. This observational data helped enrich our findings and avoid a sole reliance on retrospective self-reports.

Table 1: Overview of Data Collection

|

Interview Duration |

Interview Mode |

Pseudonym |

Gender |

|

3h 29min 23s |

Video call |

Oliver |

Men |

|

1h 13min 33s |

Face-to-face |

Tabea* |

Women |

|

1h 36min 34s |

Video call |

Shadi |

Women |

|

0h 58min 46s |

Face-to-face |

Luca* |

Men |

|

0h 28min 28s |

Video call |

Brian |

Men |

|

1h 24min 44s |

Video call |

Amelie |

Women |

|

0h 46min 46s |

Face-to-face |

Niklas* |

Men |

|

0h 42min 37s |

Face-to-face |

Simon* |

Men |

|

1h 20min 19s |

Face-to-face |

Leonie* |

Women |

|

1h 07min 28s |

Video call |

Paul |

Men |

|

1h 23min 50s |

Video call |

Ulyana |

Women |

|

0h 25min 48s |

Face-to-face |

Enric |

Men |

* Luca, Niklas, Simon, Tabea, and Leonie were each shadowed for half a day to one full day, with their explicit consent.

3.2 Data Analysis

We adopted the data analysis technique employed by Barrett et al. (2012) because it provided us with an established approach for analyzing qualitative data in the context of a study informed by practice theory. Consistent with these authors, we coded our data in four rounds, gradually moving from “local and situated patterns to cross-cutting themes and theoretical insights” (Barrett et al., 2012, p. 1453).

The first round sought to develop descriptive categories that captured the observations in our data. Exemplary codes developed in this first round included “watches Netflix and YouTube on the phone,” “keeps a 1,400-long Snapchat streak,” or “forgets about the present moment due to smartphone use.” The codes resulting from this first round were discussed by two authors to identify emerging commonalities across the participants. A key insight that arose during these discussions was that the location of individuals and where they placed their devices influenced their (dis)engagement with them.

Accordingly, the second round of coding was focused on generating more theoretical themes, particularly around the roles of “places” (where a person or a device was) and “placing” (where a device was placed).

The third round aimed to identify patterns in how places and placement influenced the dimensions of digital disconnecting for the participants. To develop “comparative themes” (Barrett et al., 2012, p. 1454), we drew on prior literature and identified commonly discussed components of digital disconnection, namely temporal, mental-emotional, and technical aspects, which we conceptualized as analytical dimensions (see Section 2.2). We then explored their relationship to “places” and “placing.” The corresponding codings are included in the appendix.

Finally, we wrote analytical summaries of each case that connected codings, emerging theoretical insights, and empirical data (Langley, 1999; Barrett et al., 2012). These summaries appear in the left column of Table A1 in the appendix and served as a basis for conceptualizing the spatial dimension of digital disconnection as a contribution to the literature.

4 Findings: Fusing the Dimensions of Digital Disconnecting in Practice

In this section, we present the cases of Oliver, Leonie, and Luca to explore how digital disconnection is enacted through the fusion of different dimensions in everyday practice. Our analysis focuses on the temporal, mental-emotional, and technical dimensions previously discussed, but also reveals the relevance of spatial configurations. That is, how place and the placement of devices shape disconnection. While we develop the spatial dimension conceptually in the theoretical implications (see Section 5), we introduce it here empirically due to its significance in participants’ lived routines.

This section presents three illustrative cases, as this selective presentation allows us to explore each case in greater depth and to show how different dimensions of disconnecting are entangled in practice. Our intent is to draw on narrative depth to enhance conceptual clarity. To support transparency and traceability, additional excerpts and analytical summaries from all interviews and observations are provided in Table A1 of the appendix.

4.1 Device Placement in Shaping Digital Disconnecting: The Case of Oliver

Reflecting on his past relationship with screens, Oliver described extended periods of high screen time as “long-term misery” (Oliver, personal communication, December 2022), where he felt that his watching of YouTube or pornography slid out of control, with significant negative impacts on his well-being and overall quality of life. In the past, such phases lasted for weeks or even months. At the time of the interview, they occurred roughly once every one or two weeks and typically lasted for only a day or half a day. This shift reflects Oliver’s ongoing efforts to reshape deeply ingrained habits and mechanisms developed over the past 15 years, dating back to childhood. While the emotional burden persisted, he had devised strategies to intervene in these patterns of engagement. Crucially, these were not merely behavior- or feature-based, but included spatial and material arrangements that configured his disconnective practices.

Central to his struggle was a particular social media platform. “YouTube,” he stated, “has been the main problem for most of my life” (Oliver, personal communication, December 2022). From a practice-theoretical perspective, YouTube is not just a branded application but a site of routinized activity in which technological configuration, mental-emotional states, and temporal rhythms converge. As Oliver would occasionally need the platform for work, disconnecting could not involve removing the app entirely; rather, it concerned altering how, when, and where it became part of daily life through changes in spatial and material arrangements.

On the technical level, Oliver blocked YouTube (a branded social media application) on his smartphone (device feature), but could access it on his laptop. There, he disabled autoplay and recommendation algorithms (features) to reduce the algorithmic pull. His occasional need for YouTube for work made a full removal impractical, creating a sense of precariousness: While access was restricted, temptation remained. In response, Oliver also developed spatial routines aimed to limit device access. When not in use, both his laptop and smartphone were stored in a cupboard in the hallway of his flat. If his phone was kept in the room, it had to be connected to the charger in a designated corner. These practices extended spatial organization; instead, they reconfigured bodily orientation and accessibility, subtly reshaping how individuals engage with their devices. As he explained:

So, if I want to go to them, I have to get up, go to the room, open the door, unlock the cupboard – multiple stages along this at which I can change my mind. […] So, the more steps between you and the object, the better (Oliver, personal communication, December 2022).

A depleted battery added another technical-temporal barrier – one more step toward regaining control. The spatial distance introduced friction into routinized engagement with digital devices and opened up moments for reflection and reorientation.

Placing also interacted with Oliver’s bodily experience. At home, he reported enjoying listening to audiobooks or music via his phone, and occasionally receiving a text message, indicated by a buzz. To check or respond to messages, the placement of the phone required him to be physically hunched over the device in an uncomfortable posture. “There can be no comfort while I use it,” he explained. “If I’m comfortable and engaging in the behavior, suddenly I lose control. Discomfort is a disconnector. A thing that separates me from the phone. Discomfort is a way of retaining control” (Oliver, personal communication, December 2022) Similarly, when watching YouTube on his laptop, he would place the device on his desk and sit “painfully upright until the YouTube video is finished” (Oliver, personal communication, December 2022).

In each example, physical posture and movement were not incidental, but a crucial component of the spatial arrangement intended to support emotional and attentional self-regulation. The spatial arrangement of the device placement intersects with embodied experience that shapes the emotional-mental dimension. The discomfort becomes a practice of remaining aware and maintaining agency in moments of vulnerability. Although Oliver was technically connected, his use of physical discomfort as a form of separation reflected a more complex relationship to digital disconnection. If we were to conceptualize disconnection as a continuum, on the mental-emotional dimension, engagement would be deliberately limited compared to moments of being drawn deeply into screens (e.g., watching YouTube videos for hours). This illustrates how disconnection is not binary, but rather involves subtle nuances in how disconnecting is enacted and felt in practice.

Oliver was not always rigid in his routines. Depending on his mental-emotional state, he would occasionally feel comfortable and “pretty safe” (Oliver, personal communication, December 2022) in taking his laptop to bed. With the internet turned off and only a text editor open, he would use it for writing. However, this proximity could become problematic in hindsight. One morning, Oliver woke to find his laptop on the floor beside his bed, left there after a writing session the night before. Its visibility and proximity triggered the thought to “just watch one video” (Oliver, personal communication, December 2022), which cascaded into four hours of uninterrupted YouTube viewing. In this instance, the spatial placement of the device and Oliver’s mental-emotional state fused in practice, re-enacting unwanted patterns of engagement. Disconnection failed due to the specific fusion of spatial, emotional, technical, and temporal elements.

In sum, Oliver’s case highlights how disconnective practices emerge from the situated interplay of spatial, technical, temporal, and emotional dimensions. Through device placement and the experience of embodied discomfort, friction emerged that reconfigured Oliver’s mental-emotional engagement, shaping how the practice unfolded. His experience underscores how spatiality can shape (dis)connective practices.

4.2 Disconnecting at the Edge: The Case of Leonie

On university days, Leonie, who was studying for a master’s degree alongside a part-time job, often moved between working in the library in the morning and at her desk at home in the afternoon. While working on a university assignment at home, she placed her smartphone behind her laptop, as shown in Figure 1.

I prefer having my phone out of my sight. My phone is a metaphor for distraction, fun, and leisure. It’s kind of overwhelming to look at it. If a candle is standing on my desk [she grabs a candle], it’s just this candle that is red and decorative. On my phone, I can check the weather, my emails and messages, Instagram, Vinted, music, and much more. (Leonie, personal communication, January 2023).

Her reflection reveals a mental-emotional association of the phone with overstimulation, distraction, and diversion. In placing the device out of view, she enacted a spatial-material arrangement aimed at supporting focused attention, revealing how emotional-mental and spatial dimensions can come together in the enactment of disconnecting.

However, this placement was not enough to prevent her from using her smartphone. Leonie checked her phone “one more time” to see if “anyone important” had messaged her, then placed it again behind her laptop, out of view, but still within reach (Leonie, personal communication, January 2023). Just six minutes later, she picked it up again, interrupting her university work. This back-and-forth (temporal dimension) continued.

While visually hiding the phone signaled an intention to disengage, the disconnective practice remained partial and unstable, as the mental-emotional and the spatial dimensions remained entangled. Due to the phone’s proximity (spatial dimension), messenger services (communication-centered channel of the technical dimension) remained easily accessible. This, along with a perceived need to stay updated and moments of boredom or frustration (mental-emotional dimension), facilitated her interrupting her work and reaching for the phone. As such, the spatial-material arrangements both supported and undermined her intent.

Disconnecting, in this instance, was not a sustained process, but a temporally fragmented and conflicted practice. Rather than resolving the tension between dimensions, Leonie’s practice brought it into focus. Disconnection here does not take the form of a clear break, but as a continually negotiated practice, at the edge of connecting.

Figure 1: Smartphone (with downward-screen positioning) placed out of Leonie’s sight behind her laptop, while she is sitting at her desk at home (place) to engage with university tasks. Photo taken by Author-1 during fieldwork. Image included with participant’s permission.

4.3 Disconnecting within Constant Connectivity: The Case of Luca

Luca’s smartphone is an almost constant companion. He places it screen-up during gaming sessions to monitor incoming messages, holds it while walking through his flat “just in case” (Luca, personal communication, December 2022) he needs it or someone contacts him, and sets it on the kitchen table to watch videos while eating. His phone appeared to be an integral, unquestioned, and useful element in his daily doings:

Well, I always have it [my mobile phone] with me. So that I can be reached by certain people. And that if I have nothing to do and simply need to wait, for example, and can’t do anything else in the meantime, I can use it as a source of occupation (Luca, personal communication, December 2022).

This statement reflects a habitual intertwining of his smartphone and its digital connectivity with idle moments in everyday life.

One reason for this ever-present proximity lies in how Luca used his phone for entertainment and education. The other reason is his sense of responsibility to remain reachable for friends and family. Luca described a hypothetical situation where a friend might urgently need help. For Luca, being unreachable for even a few hours would feel careless, perhaps even negligent. He valued others’ availability in moments of crisis and wanted to offer the same in return:

You know, something can always happen, and when somebody calls and says, ‘Look, I am having a big problem, can you help me?’ If I am unavailable in that situation, it would not be okay (Luca, personal communication, December 2022).

These mental-emotional expectations shape how spatiality, particularly device proximity, is enacted in practice. By always having his phone physically close, Luca ensured that he could respond when needed.

This was also reflected when taking walks with his dog. Over time, these evening walks “just became” what he calls “smartphone-free time,” despite not leaving his phone behind (Luca, personal communication, December 2022). Instead, he would tuck it away in his jacket pocket, listening to music using Bluetooth earphones (with which he could skip songs or adjust the volume without taking out the phone). He would bring his device with him for two reasons: access to music and remaining reachable by calls “because I want my friends to be able to reach me should there be anything important” (Luca, personal communication, December 2022). He also stated, “it must be okay to not respond for 45 minutes” (Luca, personal communication, December 2022), referring to messaging and social media, thereby drawing a distinction between communication channels. In this way, disconnecting became selective: He maintained (and wanted to maintain) technical connectivity for phone calls while being mental-emotionally detached from messaging and social media apps.

The spatial context of being outside on his walk appeared to facilitate this engagement shift. Unlike at home, where the phone tended to be visually and physically present in his routines, its out-of-sight placement, combined with the movement and familiarity of the walking route, allowed for a disconnective practice to emerge. Spatiality, then, is not simply a backdrop, but shapes how the practice is enacted: The walk emerges as a situation where disconnecting feels legitimate and emotionally untroubling. Luca’s ability to disconnect mentally and emotionally seemed to be enabled by the phone’s latent availability: placed in his pocket, within reach, but neither visible nor actively used.

This case illustrates how spatial arrangement shapes the fusion of technical, mental-emotional, and temporal elements. Technically, the phone remained powered and connected to the network, able to receive calls. The Bluetooth headphones extended its functionality, enabling minimized physical engagement. The placing of the device and the physical setting together created a context in which non-use, aside from the music streaming app navigated via his headphones, became feasible. Mentally and emotionally, Luca could detach because the risk of missing something urgent felt mitigated as a call would immediately reach him. Temporally, the walk became a routinised moment of separation, a recurring practice that “just became” his “smartphone-free time” (Luca, personal communication, December 2022).

5 Theoretical Integration: Digital Disconnecting in Practice

This section presents a theoretical integration of our findings in relation to existing theory. First, we develop a practice-based understanding of digital disconnection (i.e., digital disconnecting) to capture how different dimensions of disconnecting fuse within the concrete activities of individuals. Second, we turn our attention to the spatial context and theorize spatiality as a distinct spatial dimension of digital disconnecting. This theoretical integration lays the groundwork for our conceptual and practical contributions described in the subsequent discussion section.

Given the ubiquity of digital devices in our daily lives (Yoo, 2010; Yoo et al., 2024), we drew on the fusion view of IS (El Sawy, 2003) and explored digital disconnection through a practice-theoretical lens (Reckwitz, 2002; Feldman & Orlikowski, 2011). The vignettes of Oliver, Leonie, and Luca illustrate how disconnective practices unfold in everyday life through the interplay of different dimensions. These dimensions interact and fuse in practice, becoming manifest in concrete actions. Our findings further show that digital disconnection is not always a deliberate act (Nassen et al., 2023), but often emerges as an unfolding and situated practice (Reckwitz, 2002; Oborn et al., 2011; Wessel et al., 2019). For example, one of our participants, Shadi, forgot her phone at home, leading her to disconnect incidentally. For Luca, walking the dog “just became” what he termed his “phone-free time” (Luca, personal communication, December 2022), an emergent routine rather than a planned strategy. To better capture the unfolding nature of practices of technology (non)use, theorists have suggested using continuous terms – practice as ways of “doing” (Schatzki, 1996, p. 90), such as “ways of cooking, of consuming, of working” (Reckwitz, 2002, p. 249) – to emphasize a processual understanding. In line with this, we adopted the term “digital disconnecting” to foreground the continuously evolving and situated ways in which individuals disengage from digital technologies through everyday practices.

Our empirical data analysis revealed that, in addition to temporal, mental-emotional, and technical aspects, spatial context matters for digital disconnecting. We found that places and the placing of digital devices serve as meaningful contexts that shape how disconnecting is enacted. For example, Luca would use social media or messaging apps frequently at home, but would refrain from doing so in the outdoor context of walking his dog.

These examples demonstrate that disconnection is entangled with the experience of place and how individuals relate to their surroundings. To conceptualize this empirically grounded insight, we draw on Gieryn (2000), who framed place as “an agentic player” (p. 466) in social life, shaping and being shaped by human action. Places are more than mere geographic locations; they also comprise material form and symbolic meaning or value (Gieryn, 2000). For instance, “home” may be associated with relaxation and privacy, while the “office” might be associated with productivity and casual interactions, such as conversations with colleagues by the coffee machine. Thereby, each place interacts with the mental-emotional, temporal, and technical dimensions of disconnecting differently, leading to situated practices.

Another key spatial aspect in our participants’ practices was the placement of devices in relation to the body, as this influences how the dimensions of digital disconnection interact and fuse. For Oliver, this placement made a key difference. While charging his phone in a designated corner felt acceptable, leaving his laptop out instead of putting it away in the cupboard carried potential consequences. Moreover, while writing in bed and leaving his laptop on the floor felt fine the night before, it became problematic the next morning, as the laptop’s visible proximity prompted the thought to “just watch one video” (Oliver, personal communication, December 2022), resulting in hours of screen time. Similarly, when working on a university task, Leonie repeatedly engaged with her smartphone, even after deliberately placing it out of sight. Its physical proximity placed it within easy reach, leading to repeated self-interruptions. Whether a phone is physically perceptible in our trousers’ pocket, visible or hidden on our desk during work, or within arm’s reach versus spatially removed, each scenario presents a different spatial situation. As research has shown, the mere visible presence of one’s smartphone can evoke experiences of vigilance and distraction (Johannes et al., 2019), complicating efforts to disconnect, particularly along the mental-emotional dimension. As argued by Merleau-Ponty (2002), spatiality is not merely objective, but also embodied and situational. Accordingly, the spatial dimension of disconnection involves more than geographic coordinates: It encompasses our lived, bodily experiences of places, proximity, and distance, which are intertwined with cognitive and affective states. For Luca, walking with his dog legitimized disconnecting and made it feel emotionally sustainable. For Oliver, spatial routines introduced friction by placing devices out of immediate reach or engaging with them in physically uncomfortable ways.

These insights allow us to theorize spatiality as a distinct dimension of digital disconnecting. The spatial dimension shapes disconnective practices through its interaction with the temporal, mental-emotional, and technical dimensions. While the first three dimensions are informed by existing literature, the spatial dimension emerged inductively from our empirical analysis.

Figure 2: Digital disconnecting as enacted in practice

Figure 2 summarizes our findings and puts them into perspective within the broader digital disconnection literature. Our results show that digital disconnecting is enacted in practice through the daily activities in which individuals relate to their devices (Whittington, 2006; see also Feldman & Orlikowski, 2011). Taking a practice-based approach foregrounds the ongoing undertakings through which phenomena, such as using, disconnecting from, or reconnecting to social media, are continuously enacted. The circular arrows in Figure 2 represent that everyday doings shape the dimensions of digital disconnecting. The dimensions mutually configure each other (illustrated by their overlaps) and fuse in practice (indicated by the dashed lines), forming practices of digital disconnecting. A given practice can be located along a continuum between being “digitally connected” and “digitally disconnected.”

6 Discussion

We now turn to our discussion of our study’s conceptual contributions, theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and directions for future research.

6.1 Contributions to Research

Amid mounting concerns over digital well-being, and the topic of digital disconnection becoming a “much-discussed solution” to the downsides of mobile technology use (cf. Klingelhoefer et al., 2024), this study has explored how disconnective practices are lived and experienced, as their impact on well-being depends on more than the act of disconnection itself. Our study makes two conceptual contributions to research on digital disconnection and well-being in the context of everyday mobile technology use. First, we conceptualize digital disconnecting through a practice-based lens as an emergent, ongoing practice rather than a singular act, unfolding both deliberately and incidentally. How disconnective practices relate to digital well-being depends on how temporal, mental-emotional, technical, and spatial dimensions are enacted in specific situations. Second, we theorize spatiality as a distinct and relevant dimension of digital disconnecting, encompassing both the notion of place and the placing of devices.

Drawing on the fusion view in IS research (El Sawy, 2003) and on practice theory, our first contribution is to conceptualize digital disconnection not as a deliberate act (Nassen et al., 2023), but as an unfolding and situated practice (Reckwitz, 2002; Oborn et al., 2011; Wessel et al., 2019), captured by the continuous term “digital disconnecting.” This is particularly useful for unpacking how people engage in digital disconnecting over time. This alternative conceptualization matters, as individuals often face challenges disconnecting from devices and platforms (Nguyen, 2023), underscoring the need for further nuanced insights into how such struggles play out in everyday life. Earlier work has meaningfully explored temporal (e.g., Jorge, 2019; Rosenberg & Vogelman-Natan, 2022; Farooq et al., 2023; Šimunjak, 2023; Marx et al., 2024), mental-emotional (e.g., Park & Kaye, 2019; Cai et al., 2020; Gerlach & Cenfetelli, 2020; Vanden Abeele & Nguyen, 2023), and technical aspects (e.g., Lyngs et al., 2019; Meier & Reinecke, 2021; Nguyen, 2021) of deliberate digital disconnection. Our study demonstrates the value of conceptualizing these aspects as interrelated dimensions that dynamically fuse in practice (El Sawy, 2003). This provides us with a conceptual language and analytical lens to understand how the deep embedding of digital devices into everyday life and their reciprocal shaping of it unfold in practice (Yoo, 2010; Baskerville et al., 2019; Yoo et al., 2024), and why this entanglement poses a struggle for many individuals wishing to disconnect. These dimensions form a continuum that moves beyond binary notions of being online or offline, connected or disconnected. Conceptualizing digital disconnecting as a continuous practice enables a nuanced understanding of how disconnective practices unfold in situ, embedded in the context of everyday life.

Prior research has often framed digital disconnection as the temporary and deliberate non-use of devices, platforms, features, and/or contents (Nassen et al., 2023), such as reducing screentime duration or frequency of smartphone use with the help of device settings or by adhering to rules (Vanden Abeele et al., 2024, p. 24). Such deliberation, as our study shows, also emerges in practice. Individuals like Oliver might employ known disconnection strategies, such as intending to limit screen time; however, their enactment is key to whether these strategies can be effective. This is why a practice-based approach complements earlier literature that conceptualizes digital disconnection as a strategic action by instead foregrounding digital disconnecting as an emergent, dynamic practice shaped by the continual configuring and reconfiguring of its underlying dimensions. Moreover, our findings show that disconnective practices may involve deliberate intent, though it does not have to per se. Intent is only one pathway; disconnecting can also emerge incidentally, as a by-product of doing other things, often tied to certain places.

The second contribution of our study centers on how we conceptualize the dimensions of digital disconnecting, with particular emphasis on theorizing the spatial dimension as meaningful and distinct. When digital disconnecting is enacted in practice, it becomes tangible that the bodily experience of the spatial context shapes how the temporal, mental-emotional, and technical dimensions are configured and fused. So far, spatiality has remained underacknowledged in prior research. For instance, while Vanden Abeele et al. (2024) highlighted the importance of “environment-fit” in their framework of digital disconnection, this aspect remains under-theorized. By employing a practice theory perspective, we identify the importance of the spatial context and contribute to the literature by framing it as a distinct dimension of digital disconnecting.

Taken together, these insights point toward a more holistic and situated conceptualization of digital disconnecting, understood as comprising a temporal, mental-emotional, technical, and spatial dimension whose dynamic interplay shapes disconnective practices. By conceptualizing disconnecting as an emergent, spatially embedded practice, our findings contribute to a richer understanding of how attaining digital well-being – defined as a dynamic “experiential state of optimal balance between connectivity and dysconnectivity” (Vanden Abeele, 2020, p. 932) – involves navigating complex, embodied, and situated engagements with technology in everyday life.

6.2 Practical Implications

Our findings offer two practical implications for engaging in disconnective practices that restore and enhance digital well-being. First, that individuals often disconnect as a by-product of engaging in other activities, often tied to different places, suggests that digital well-being efforts could benefit from supporting these everyday practices, rather than relying solely on adherence to behavioral guidelines or feature-based interventions (Nguyen, 2021). Second, device placement emerged as a low-effort yet influential practice that shapes how individuals engage with or disconnect from their devices. Placing devices not only out of sight but assigning them a specific location in the home to increase physical distance may help foster habitual engagement in disconnective practices and disrupt connective routines. These implications highlight the value of considering the spatial context of everyday life in the design of digital well-being interventions.

6.3 Limitations and Future Research

While our qualitative approach offers rich insights into everyday disconnective practices, it also comes with certain limitations. As with all qualitative research, our findings aim to contribute to conceptual, not statistical, generalization (Lee & Baskerville, 2003, 2012) by unpacking how digital disconnecting is enacted in everyday life through practice. This theoretical contribution was prioritized over representativeness.

Second, our sample presents certain limitations. Our study was based on a relatively small sample size comprising 12 interviews and 5 observations. Participants were between the ages of 21 and 34 and living in Germany or Spain, except for two individuals residing in South Korea. While four participants originated from outside Germany or Spain (the United Kingdom, Iran, Ukraine, and the United States), the overall cultural diversity was limited. This may constrain the transferability of our findings to older age groups, other world regions, or individuals with limited access to digital technologies.

Thirdly, regarding modality, half of the interviews were conducted via video calls, which can lead to shorter or less in-depth conversations compared to in-person formats (Irvine, 2011). However, interview durations and the richness of participant responses suggest that the video medium did not significantly compromise our data quality. Conducted in late 2022 and early 2023 during the COVID-19 pandemic, the interviews may reflect pandemic-related shifts in how participants engaged with and disconnected from digital technologies.

Fourthly, our reliance on retrospective self-reports represents a methodological limitation, as with many interview-based qualitative studies (Jerolmack & Khan, 2014). Although this approach is widely used in digital disconnection research (e.g., Floros et al., 2021; Nguyen, 2021, 2023; Agai & Agai, 2022), self-reporting may invite biased or incomplete representations, especially on topics shaped by social norms. For instance, mobile technology use may be framed as aspirational by research participants. Despite this, we found that the participants were often self-reflective and critical of their own behavior.

Future research could further explore the role of place and placement in shaping disconnective practices, including the development of distinct spatial strategies and their effectiveness. Given that mobile media use is not bound to specific locations, to what extent and under what conditions place configures disconnective practices remain open questions. It may also be valuable to further examine how concrete spatial aspects, such as proximity, positioning, visibility, physical perceptibility, and the presence of physical boundaries, shape everyday (dis)engagement with devices. While we included embodied aspects within spatiality, we did not analyze embodiment as a separate dimension; future research could further develop this perspective. Future work could also assess the relative effectiveness of spatial strategies compared to more established approaches (e.g., Nguyen, 2021; Vanden Abeele et al., 2024) and explore how these effects generalize across diverse populations and situational contexts.

7 Conclusion

With growing concern over the impact of constant connectivity, individuals and institutions alike are seeking ways to disconnect from digital technologies to foster well-being in a digital world. Our study contributes to this discussion by shifting the focus from disconnection as a strategic act to disconnecting as a situated practice that can happen both deliberately and incidentally, shaped by the varying fusion of mental-emotional, technical, and spatial dimensions over time. In particular, we foregrounded the role of place and placement for practices of disconnecting. The findings from our practice theory-based study open new avenues for theorizing, practically engaging in, and designing for disconnective practices.

Acknowledgement

We thank our editor Dr. Hannes-Vincent Krause and the three anonymous reviewers for their support and thoughtful feedback during the review process.

References

Agai, M. S., & Agai, M. S. (2022). Disconnectivity synced with identity cultivation: Adolescent narratives of digital disconnection. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 27(6). https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac025

Bansal, P. (Tima), & Corley, K. (2011). The coming of age for qualitative research: Embracing the diversity of qualitative methods. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 233 – 237. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.60262792

Bardhan, I., Chen, H., & Karahanna, E. (2020). Connecting systems, data, and people: A multidisciplinary research roadmap for chronic disease management. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 44(1), 185 – 200

Barrett, M. et al. (2012). Reconfiguring boundary relations: Robotic innovations in pharmacy work. Organization Science, 23(5), 1448 – 1466. https://doi.org/doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0639

Baskerville, R L., Myers, M. D., & Yoo, Y. (2019). Digital First: The Ontological Reversal and New Challenges for Information Systems Research. MIS Quarterly, 44(2), 509 – 23. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2020/14418

Bossio, D., & Holton, A. E. (2021). Burning out and turning off: Journalists’ disconnection strategies on social media. Journalism, 22(10), 2475 – 2492. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919872076

Bucher, T. (2020). Nothing to disconnect from? Being singular plural in an age of machine learning. Media, Culture & Society, 42(4), 610 – 617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720914028

Büchler, N., Ter Hoeven, C. L., & Van Zoonen, W. (2020). Understanding constant connectivity to work: How and for whom is constant connectivity related to employee well-being?. Information and Organization, 30(3), 100302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2020.100302

Burr, C., & Floridi, L. (2020). Ethics of digital well-being: A multidisciplinary approach. Springer.

Cai, W., McKenna, B., & Waizenegger, L. (2020). Turning it off: Emotions in digital-free travel. Journal of Travel Research, 59(5), 909 – 927. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519868314

El Sawy, O. A. (2003). The IS core IX: The 3 faces of IS identity: Connection, immersion, and fusion. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 12. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01239

Farooq, A., Dahabiyeh, L., & Maier, C. (2023). Social media discontinuation: A systematic literature review on drivers and inhibitors. Telematics and Informatics, 77, 101924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2022.101924

Feldman, M. S., & Orlikowski, W. J. (2011). Theorizing Practice and Practicing Theory. Organization Science, 22(5), 1240 – 53. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0612

Floros, C. et al. (2021). Imagine being off-the-grid: Millennials’ perceptions of digital-free travel. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(5), 751 – 766. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1675676

Gerlach, J. P., & Cenfetelli, R. T. (2020). Constant checking is not addiction: A grounded theory of IT-mediated state-tracking’, MIS Quarterly, 44(4), 1705 – 1732. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2020/15685

Gieryn, T. F. (2000). A space for place in sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 463 – 496. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.463

Gregory, R. W. et al. (2020). The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Data Network Effects for Creating User Value. Academy of Management Review, 46(3), 534 – 51. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2019.0178

Hepp, A. (2020). Deep mediatization. Routledge.

Hultin, L. (2019). On Becoming a Sociomaterial Researcher: Exploring Epistemological Practices Grounded in a Relational, Performative Ontology. Information and Organization, 29(2), 91 – 104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2019.04.004

Irvine, A. (2011). Duration, dominance and depth in telephone and face-to-face interviews: A comparative exploration. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 10(3), 202 – 220. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691101000302

Jerolmack, C., & Khan, S. (2014). Talk is cheap: Ethnography and the attitudinal fallacy. Sociological Methods & Research, 43(2), 178 – 209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124114523396

Johannes, N. et al. (2019). Hard to resist?: The effect of smartphone visibility and notifications on response inhibition. Journal of Media Psychology, 31(4). 214 – 225. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000248

Jorge, A. (2019). Social media, interrupted: Users recounting temporary disconnection on Instagram. Social Media + Society, 5(4), 2056305119881691. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119881691

Jorge, A., Amaral, I., & de Matos Alves, A. (2022). “Time well spent”: The ideology of temporal disconnection as a means for digital well-being. International Journal of Communication, 16, 1551 – 1572

Kautz, K., & Jensen, T. B. (2013). Sociomateriality at the royal court of IS. A jester’s monologue. Information and Organization, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2013.01.001

Klingelhoefer, J., Gilbert, A., & Meier, A. (2024). Momentary motivations for digital disconnection: An experience sampling study. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 29(5), 13. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmae013

Knott, E. et al. (2022). Interviews in the social sciences. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 2(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-022-00150-6

Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 691 – 710.

Lebovitz, S., Lifshitz-Assaf, H., & Levina, N. (2022). To engage or not to engage with AI for critical judgments: How professionals deal with opacity when using AI for medical diagnosis. Organization Science, 33(1), 126 – 148. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.1549

Lee, A. S., & Baskerville, R. L. (2003). Generalizing Generalizability in information systems research. Information Systems Research, 14(3), 221 – 243. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.14.3.221.16560

Lee, A. S, & Baskerville, R. L. (2012). Conceptualizing generalizability: New contributions and a reply. MIS Quarterly, 36(3), 749. https://doi.org/10.2307/41703479

Lorenz, J., Kruse, L. C., & Recker, J. (2024). Creating and capturing value with physical-digital experiential consumer offerings. Journal of Management Information Systems, 41(3), 779 – 811. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2024.2376386

Lyngs, U. et al. (2019). Self-control in cyberspace: Applying dual systems theory to a review of digital self-control tools. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, pp. 1 – 18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300361

Marx, J., Mirbabaie, M., & Turel, O. (2024). Digital detox: A theoretical framework and future research directions for information systems. Information & Management, 104068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2024.104068

Mazmanian, M., Orlikowski, W. J., & Yates, J. (2013). The autonomy paradox: The implications of mobile email devices for knowledge professionals. Organization Science, 24(5), 1337 – 1357. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1120.0806

Meier, A., & Reinecke, L. (2021). Computer-mediated communication, social media, and mental health: A conceptual and empirical meta-review. Communication Research, 48(8), 1182 – 1209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220958224

Merleau-Ponty, M. (2002). Phenomenology of perception: An introduction. Routledge.

Mihailidis, P. (2014). A tethered generation: Exploring the role of mobile phones in the daily life of young people. Mobile Media & Communication, 2(1), 58 – 72. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157913505558

Möhlmann, M. et al. (2021). Algorithmic management of work on online labour platform: When matching meets control’, MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 45(4)

Mols, A., & Pridmore, J. (2021). Always available via WhatsApp: Mapping everyday boundary work practices and privacy negotiations. Mobile Media & Communication, 9(3), 422 – 440. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157920970582

Morrison, S L., & Gomez, R. (2014). Pushback: Expressions of Resistance to the “Evertime” of Constant Online Connectivity. First Monday, 19(8). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v19i8.4902

Nassen, L.-M. et al. (2023). Opt-out, abstain, unplug. A systematic review of the voluntary digital disconnection literature. Telematics and Informatics, 81, 101980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2023.101980

Natale, S., & Treré, E. (2020). Vinyl won’t save us: Reframing disconnection as engagement. Media, Culture & Society, 42(4), 626 – 633. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720914027

Nguyen, M. H. (2021). Managing social media use in an “always-on” society: Exploring digital wellbeing strategies that people use to disconnect. Mass Communication and Society, 24(6), 795 – 817. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2021.1979045

Nguyen, M. H. (2023). “Maybe I should get rid of it for a while…”: Examining motivations and challenges for social media disconnection. The Communication Review, 26(2), 125 – 150. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714421.2023.2195795

Nguyen, M. H., Büchi, M., & Geber, S. (2022). Everyday disconnection experiences: Exploring people’s understanding of digital well-being and management of digital media use. New Media & Society, 146144482211054. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221105428

Nguyen, M. H., & Hargittai, E. (2023). Digital disconnection, digital inequality, and subjective well-being: a mobile experience sampling study. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 29(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmad044

Oborn, E., Barrett, M., & Davidson, E. (2011). Unity in diversity: Electronic patient record use in multidisciplinary practice. Information Systems Research, 22(3), 547 – 564. https://doi.org/doi:10.1287/isre.1110.0372

Orlikowski, W. J. (1996). Improvising organizational transformation over time: A situated change perspective. Information Systems Research, 7(1), 63 – 92. https://doi.org/10.2307/23010790

Orlikowski, W. J., & Iacono, C. S. (2001). Research commentary: Desperately seeking the “IT” in IT research – A call to theorizing the IT artifact. Information Systems Research, 12(2), 121 – 134. https://doi.org/DOI%252010.1287/isre.12.2.121.9700

Orlikowski, W. J., & Scott, S. V. (2008). Sociomateriality: Challenging the separation of technology, work and organization. Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 433 – 474. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520802211644

Orlikowski, W. J., & Scott, S. V. (2015). The algorithm and the crowd: Considering the materiality of service innovation. MIS Quarterly, 39(1), 201 – 216. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.1.09

Park, C. S., & Kaye, B. K. (2019). Smartphone and self-extension: Functionally, anthropomorphically, and ontologically extending self via the smartphone. Mobile Media & Communication, 7(2), 215 – 231. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157918808327

Radtke, T. et al. (2022). Digital detox: An effective solution in the smartphone era? A systematic literature review. Mobile Media & Communication, 10(2), 190 – 215. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579211028647

Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), 243 – 263. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310222225432

Rosenberg, H., & Vogelman-Natan, K. (2022). The (other) two percent also matter: The construction of mobile phone refusers. Mobile Media & Communication, 10(2), 216 – 234. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579211033885

Sarker, S. et al. (2019). The sociotechnical axis of cohesion for the IS discipline: Its historical legacy and its continued relevance. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 43(3). https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2019/13747

Schatzki, T. R. (1996). Social practices: A Wittgensteinian approach to human activity and the social. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511527470

Schatzki, T. R. (2025). Agency. Information and Organization, 35(1), 100553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2024.100553

Šimunjak, M. (2023). “You have to do that for your own sanity”: Digital disconnection as journalists’ coping and preventive strategy in managing work and well-being. Digital Journalism, 0(0), 1 – 20. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2153711

Turkle, S. (2008). Always-on/always-on-you: The tethered self. In J. E. Katz (Ed.), Handbook of mobile communication studies (pp. 121 – 138). The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262113120.003.0010

Vaast, E., & Pinsonneault, A. (2022). Dealing with the social media polycontextuality of work. Information Systems Research, 33(4). https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2022.1103

Van Bruyssel, S., De Wolf, R., & Vanden Abeele, M. (2023). Who cares about digital disconnection? Exploring commodified digital disconnection discourse through a relational lens. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 13548565231206504. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565231206504

Vanden Abeele, M. M. (2020). Digital wellbeing as a dynamic construct. Communication Theory, 31(4), 932 – 955. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtaa024

Vanden Abeele, M.M.P. and Nguyen, M.H. (2022). Digital well-being in an age of mobile connectivity: An introduction to the Special Issue. Mobile Media & Communication, 10(2), 174 – 189. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579221080899

Vanden Abeele, M. M., & Nguyen, M. H. (2023). Digital media as ambiguous goods: Examining the digital well-being experiences and disconnection practices of Belgian adults. European Journal of Communication, 02673231231201487. https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231231201487