Disinformation Resilience in Backsliding Democracies

Media Trust, Civil Society, and Institutional Capture

1 Introduction

Disinformation is often considered one of the main threats to democracies, but strategies to counter it systematically remain debated (OECD, 2022; Turcilo & Obrenovic, 2020; West, 2017). The spread of disinformation is often connected to the trend of democratic backsliding; the deliberate dismantling of democratic norms and institutions by political elites (Colomina et al., 2021; Maati et al., 2023; Reisher, 2022; Wikforss, 2023). Yet, disinformation research focuses disproportionately on so-called consolidated Western democracies, especially the United States. 1 To understand the structural features relevant to exposure and resilience to disinformation in countries experiencing democratic backsliding, we first apply the framework established by Humprecht et al. (2020) beyond consolidated democracies. The framework identifies features of a country’s political, media, and economic landscape that influence resilience to disinformation at the societal (rather than individual) level.

We extend this framework to the Visegrád countries – Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia – formerly authoritarian communist countries that are now experiencing democratic backsliding and an increasingly “illiberal public sphere” (Štětka & Mihelj, 2024). Evidence of these phenomena are emerging in Czechia (Cianetti & Hanley, 2021; Hanley & Vachudova, 2019), and there is broad consensus about Hungary’s new status as a competitive authoritarian regime (Krekó & Enyedi, 2018; Végh, 2022). Similarly, scholars argue that under the rule of the Law and Justice Party (PiS) – until December 2023 –Poland regressed to a semi-consolidated democracy (Wójcik & Wiatrowski, 2022), and serious challenges to liberal democracy have been identified in Slovakia (Mesežnikov & Gyárfášová, 2018). The variation in the degree of democratic erosion in these countries, combined with their shared history and cultural interconnectivity, makes them an excellent set of cases for clarifying the potential relationships between societies’ resilience to disinformation and the practice of democracy.

There may be multiple reasons to expect that the original framework, which was designed for consolidated democracies, is not sufficient to explain resilience to disinformation in other countries. Research outside of established democracies indicates that trust in the media in these countries is conditioned by popular wisdom and personal experience (Alyukov, 2023), social interactions (Pasitselska, 2022), and historical contexts (Pjesivac et al., 2016). In the process of applying the original framework, we empirically identify several key differences in resilience features between democratic and eroding regimes. For example, we observe that consuming and trusting politically captured media that disseminate disinformation should be interpreted as lower resilience in eroding regimes. Therefore, we use our initial findings to suggest advances to the framework in application to eroding democracies and then empirically apply our advanced framework.

To do so, we integrated V-Dem’s (Coppedge et al., 2019) Media Capture Index to account for the ownership features of a country’s media landscape. Media capture refers to the degree of control exercised over the media by political elites, which enables the latter to define the public agenda and, by extension, public opinion (Hallin & Mancini, 2004; Schiffrin, 2021). We also identify the part played by civil society in countries experiencing democratic backsliding, adding a Civil Society Index to account for variation in the scope of civic spaces and pro-democratic mass mobilization. The Civil Society Index helps highlight the role of non-government actors, which have been shown to bolster democratic practice and improve societal resilience to disinformation (Bernhard, 2020; Eisen et al., 2019).

In the empirical application of our advanced framework, we identify that Slovakia and Czechia fit the “polarized” cluster alongside countries in southern Europe identified by Humprecht et al. (2020), with Slovakia demonstrating the most resilience. Poland and Hungary are distinct from these countries both in their degree of media capture and in their civil society responses, with Hungary being the least resilient. Our application highlights the importance of these additional dimensions in identifying variation among countries experiencing democratic backsliding. We then apply our advanced framework back to the consolidated democracies used in Humprecht et al.’s (2020) original study, demonstrating that our advancements also improve our comprehension of resilience to disinformation in these countries. When applied to both the Visegrád group and the European countries in Humprecht et al.’s (2020) study, our advanced framework reveals that the degree of media capture conditions the relationship between media trust and societal resilience to disinformation.

Consequently, our additions to the original framework have implications for understanding the relationship between resilience to disinformation and the practice of democracy in consolidated and backsliding democracies alike. We contend that integrating the dynamics of media capture and civil society enables a more comprehensive view of societies’ resilience to disinformation.

2 Disinformation Resilience & Democratic Backsliding

In line with Humprecht et al. (2020), we analyzed resilience to disinformation at the national level, understood as the result of the macro-level features of a society. These macro-level features structure individuals’ resilience to disinformation and represent “the capacity of groups… to sustain and advance their well-being” (Lamont & Hall, 2013, p. 2) in the face of disinformation. This approach differs from those offered by media psychology or studies on the individual micro effects of disinformation (Hameleers, 2023; Zerback et al., 2021).

The goal of disinformation is to shift people’s perceptions of reality and, ultimately, alter their behavior. Many actors in established democracies perceive disinformation campaigns as a growing threat (Colomina et al., 2021) because these circumvent their norms and institutions to influence the population, thereby weakening societal structures, shaping public opinion, and (de)mobilizing citizens (Humprecht et al., 2023). Disinformation is therefore defined by its status as not only false but also carrying the intention to mislead (Fallis, 2015) or cause harm (Pathak et al., 2021) – that is, “malicious” intent (Diaz Ruiz & Nilsson, 2023; Freelon & Wells, 2020).

Disinformation is an attempt to disturb democratic processes by influencing the decisions of individuals and institutions (Tenove, 2020). Exposure to conspiracy narratives reduces political participation by increasing people’s perception of their own political powerlessness or uncertainty and decreases trust in governments (Einstein & Glick, 2015; Jolley & Douglas, 2014). Disinformation strategically shapes information availability and can affect collective opinion and decision-making (Woolley & Howard, 2018) by creating a “manufactured consensus” (Woolley & Guilbeault, 2017). In response, democratic institutions and societies attempt to minimize the dissemination of disinformation in their public spheres (Cipers et al., 2023). Therefore, we explore which factors determine resilience to disinformation at the societal level.

Resilience to disinformation refers to the ability of individuals and societies to identify, resist, and mitigate the harmful effects of disinformation. From a macro perspective, we focus on the processes, platforms, and features that are essential for democratic deliberation at the societal level. Humprecht et al. (2020) identify three overarching shifts in recent decades that have contributed to lowering societies’ resilience to disinformation; these occurred in the political environment, the media environment, and the economic environment. We review each area in detail in the supplementary material.

Humprecht et al. (2020) also observe three clusters of resilience to disinformation in their sample of 18 consolidated Western countries: the “media supportive, more consensual cluster” in Western Europe and Canada; the “polarized cluster” in Southern Europe; and the US as an outlier case with low trust, high polarization, and fragmentation. We therefore seek to understand how this finding travels to countries experiencing democratic backsliding. This is because a decline of democracy in terms of freedom of the press, the rise of authoritarian governments undermining democratic institutions, and the capture of media organizations (Schiffrin, 2018, 2021) can fundamentally alter societies’ resilience to disinformation.

For instance, when authoritarian parties take control of public service media, roll back the rule of law by dismantling the independence of courts, or take civil rights away from groups in society, as the PiS government did in Poland, increasing polarization and protests against government policies may not be destabilizing to democracy but can instead be seen as an expression of the fight for democracy. Similarly, trust in media is not beneficial to democracy in all circumstances (see, e.g., Alyukov, 2023; Pasitselska, 2022; Pjesivac et al., 2016; Szostek, 2018): in a situation of media capture by government parties and reduced media independence, citizens should be skeptical and less trusting. Accordingly, the use of social media for news is highest where trust in news media is the lowest in Europe, such as in Greece, Bulgaria, or Hungary (Newman et al., 2022). Consequently, our application of Humprecht et al.’s (2020) framework beyond consolidated democracies will require adjustments for countries experiencing democratic backsliding.

Thus, the goal of this study is to:

1) Apply the framework of resilience to disinformation to the Visegrád group countries as cases experiencing democratic backsliding.

2) Advance the applicability of the framework of resilience to disinformation to countries experiencing democratic backsliding and validate these advancements using the countries covered by the original framework.

3 The Visegrád Group

The Visegrád Group refers to political cooperation between the four countries of Czechia, Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia. These central European countries are united by their membership of the European Union (EU), shared economic and political interests, and a common legacy of having previously been within the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence (Schütz & Bull, 2017). After the Cold War, these countries were seen as frontrunners in post-communist democratic transformation. The challenges they faced during democratization were multifaceted, with internal factors such as domestic political dynamics and institutional weaknesses playing a central role in shaping their trajectories (Bakke & Sitter, 2021; Hornat, 2021). EU conditionalities further influenced the process of democratization in the region (Grabbe, 2006). More recently, Russia has expressed opposition to the region’s further integration with EU institutions (Cabada, 2022; Waisová, 2020). We briefly discuss the countries’ media ecosystems and their relation to democratic backsliding and disinformation.

Czechia

In Czechia, much of the online disinformation is spread on websites and social media platforms with connections to Czech politicians with links to Russia, including former president Miloš Zeman and former prime minister Andrej Babiš (Cabada, 2022). The historical ties between the Czech Republic and the former Soviet Union – notably the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 – may shape public perceptions and, in some cases, influence resilience to Russian disinformation narratives (Bokša, 2019). While contemporary Russia often positions itself as the successor to the Soviet Union (Chaisty & Whitefield, 2022), the legacy of Soviet influence and occupation continues to affect attitudes in Czech society (Heissler, 2018). Cultural familiarity with Russia may make disinformation messaging resonate more strongly, particularly when it appeals to shared historical or ideological frames, such as anti-Western sentiment or nostalgia for stability during the communist era. 2 Disinformation campaigns may therefore exploit lingering societal divisions or grievances related to the transition from communism to democracy, with some Czechs viewing the Soviet period as a period of stability or ideological alignment and others seeing it as a time of oppression.

In particular, the Mafra media group owned by Babiš continued to provide favorable coverage to his ANO 2011 party despite widespread evidence of his misuse of EU funds (Bernhard et al., 2019). The pro-democratic mobilization that helped remove Babiš from office was therefore accompanied by a transformation of the media landscape (Bernhard et al., 2019), which Freedom House described as “politically imbalanced due to the concentration of media ownership in the country” (Buštíková, 2021) and dominated by conglomerates that secured comprehensive funding during Babiš’s tenure. These continue to ensure the former prime minister’s influence over coverage (Sybera, 2022).

Poland

Disinformation in Poland tends to focus on government activities, the role of the Catholic Church, and “culture war” issues such as LGBTQ rights (Rosińska, 2021). Russian influence is less prominent in Poland than in other Visegrád countries (Waisová, 2020), largely due to a combination of historical mistrust of the Soviet Union and Russia and Poland’s current geopolitical objectives (Chappell, 2021). For example, Poland is the only Visegrád country to host US troops permanently on its territory (Waisová, 2020). At the same time, narratives of pan-Slavism – an ideology often associated with Russian attempts to foster solidarity among Slavic nations – are visible in some cultural and ideological spaces (Bokša, 2019) and have been adopted by fringe political actors (Witkowski, 2023).

Online disinformation in Poland is disproportionately produced by a small group of suspected right-wing accounts with links to the PiS (Gorwa, 2017). This pattern continues the previous strategy of taking over the state broadcaster (TVP) such that the service “is now widely seen on the left as an official channel for PiS propaganda” (Gorwa, 2017, p. 12). 3 Consequently, Poland’s Freedom of Press ranking fell to its lowest position ever (66th) in 2022 (Reporters Without Borders, 2023), 4 with identifiably false content featuring in mainstream news coverage as a result of lower journalistic standards, seeking audiences’ attention, and the dominance of corporate interests (Popiołek et al., 2021).

Hungary

Hungary has experienced more pronounced autocratization than its Visegrád neighbors (Haglund et al., 2022). Since Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz party came to power for the second time in 2010, Hungary has had the lowest democracy standards in the EU (Coppedge et al., 2019). This trend has been accompanied by disruption to academic practices and the almost complete capture of the media landscape by Fidesz (Fillipov, 2020; Szicherle & Molnár, 2021; Urbán et al., 2023). Spyware software is used to silence critics (Walker, 2022), and government-aligned oligarchs systematically bought off media outlets after foreign investors withdrew due to political pressure (Štětka, 2015).

Domestic factors such as state-aligned media networks and home-grown disinformation producers have shaped public opinion and helped consolidate power for the governing party. A network of Fidesz-owned or supportive media outlets has been instrumental in spreading narratives that reinforce government policies and polarize the electorate (Bátorfy & Urbán, 2020; Urbán et al., 2023). However, Russian disinformation, a feature of disinformation in the other Visegrád countries to varying degrees, is “largely absent in Hungary… [because] the public broadcaster effectively plays that role” (Griffen, 2020, p. 59). Fidesz benefits from this dynamic as disinformation divides the Hungarian electorate and provides cover for the further erosion of democratic norms and standards (Reisher, 2022). Fidesz’s approach in Hungary has therefore been seen as a “roadmap” for countries like Poland (Štětka & Mihelj, 2024).

Slovakia

In the 1990s, under Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar, Slovakia experienced periods of democratic backsliding characterized by violations of constitutionalism and the basic rules of the liberal-democratic order (Gluchman, 2011). As a result, democratic consolidation took longer than in its Visegrád neighbors. In the early 2000s, Slovakia implemented reforms that included commitments to democratic principles (Mokrá & Kováčiková, 2023). Yet, problems have persisted. Influential oligarchs interfere with journalistic independence, with the murder of journalist Ján Kuciak evidencing the growing danger faced by independent media sources (Burčík, 2019; Urbániková & Haniková, 2024) in a media system containing a “vast ecosystem of outlets that promulgate problematic content” (Hajdu et al., 2021).

The country’s positive attitudes towards Russia and pan-Slavism also hinder the population’s ability to identify widespread Russian disinformation (Hajdu et al., 2021). Websites that contain disinformation are frequently used media sources, and articles utilizing pan-Slavic cultural narratives are widely shared on social media (Čižik & Masariková, 2018). The prevalence of disinformation in Slovakia has become well understood in the digital era (Hlatky, 2023; Škarba & Višňovský, 2023; Wenzel et al., 2023), with disinformation narratives observed in the output of professional media, politicians, and experts in the 2020 parliamentary elections (Kӧles et al., 2021).

Although widely understood as a turn towards illiberal populism, the 2023 parliamentary elections also saw protests against the ultimately triumphant Smer-SSD party, which was broadly seen as liable to political corruption and under the influence of oligarchic and criminal networks (Stoklasa, 2023). The government elected in 2023 appears unlikely to strengthen structures countering disinformation given Prime Minister Robert Fico’s close connections to pro-Russian groups. Since coming to power, Fico’s government has undertaken a “purge” of the public state media RTVS (Chastard, 2024).

4 Applying the Framework

To understand the dynamics of disinformation resilience in backsliding democracies, we started by applying the framework developed by Humprecht et al. (2020). The authors of the original framework identified seven indicators, grouped into the political environment, media environment, and economic environment, to explain variation in resilience to online disinformation. We used the same sources as the original study and provide further details about the data and indicators in the supplementary material.

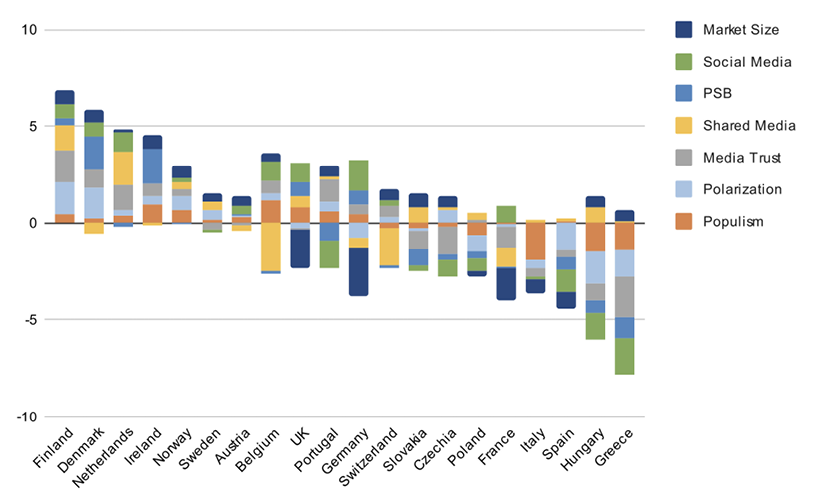

We began by plotting the performance of the various indices for the European countries covered in the original framework in Figure 1, with the addition of the four Visegrád countries. In this visualization, a stacked bar of standardized values represents the relative resilience of each country, replicating the original study. Values approaching 10 indicate higher resilience, and those nearer to – 10 indicate lower resilience.

Figure 1: Resilience indicators (original framework)

Note: Standardized index values. Higher values mean a higher performance on the resilience indicators. The figure is an extension of the study by Humprecht et al. (2020) adding Slovakia, Poland, Czechia, and Hungary.

In this application of the original framework, the Visegrád countries were all positioned in the lower half of the sample. Specifically, Slovakia, Czechia, and Poland were in the third quarter, and Hungary was in the fourth quarter together with southern European countries, identified in the original study as the “polarized” cluster (Humprecht et al., 2020). These initial results from the Visegrád countries seemed to support the original framework’s consistency given that performance on the resilience indicators aligned with exposure to disinformation.

5 Advancing the Framework

Though the Visegrád countries broadly aligned with our expected positioning the original framework, we identify several challenges in applying this model to countries experiencing democratic backsliding. Of the Visegrád countries, Poland showed the highest trust in the media overall and in the outlets that respondents used. According to the framework, this strengthens resilience. Yet, these high rates of trust do not align with reports about the Polish media landscape (Coppedge et al., 2019; Reporters Without Borders, 2023), which indicate that the country has experienced a more drastic dissolution of independent and free journalism than Czechia or Slovakia. When a society upholds the freedom of the press, trust in media overall (the first component of the Media Trust Index) is expected to be lower. This relationship requires people to be critical of the undermining of this democratic principle and be able to both detect and reject widening opportunity structures for disinformation. Higher trust in captured media could instead indicate lower sensitivity to these processes, resulting in lower resilience to disinformation.

Whether “trust in news that I use” (the second component of the Media Trust Index) is also vulnerable to these deficiencies in countries experiencing democratic backsliding depends on media choices at the individual level. For example, an individual consuming and trusting a media source that is biased or that has been captured by the governing party, such as the Mafra group in Czechia, is more likely to be exposed to disinformation. Conversely, consuming alternative media or having low trust in state-controlled sources can reduce exposure to disinformation in these countries. For example, consuming alternative media sources in Hungary might offer resilience to government-endorsed disinformation (Goh, 2015). Hungary’s low trust in news media overall but comparatively high trust in the news media people use could be an indicator of this pattern. However, without more information about the sources that people favor and trust at the individual level, the existing framework is of limited analytical value. The deterioration of the media landscape is less severe in Slovakia and Czechia than in Poland and Hungary, yet these countries perform even lower than Hungary in the Media Trust Index. It may be that in these democracies, higher sensitivity to and critique of the attempted erosions may instead signify greater resilience to disinformation.

The Shared Audience Index could also be a problematic indicator outside of consolidated democracies if the highest audience share is concentrated on a public broadcaster that has become an instrument of the government or an outlet controlled by partisan oligarchs. In Hungary, this indicator forms an important component of positive values of resilience. Yet, 60% of the Hungarian population consume their news via RTL Klub, one of the few remaining foreign-funded broadcasters in Hungary, which regularly emphasizes its independence from the governing regime (Bede, 2018; Newman et al., 2022). Similarly, in Poland, the outlet with the highest share is TVN, a critical and foreign-funded TV outlet that has experienced frequent attempts by PiS to undermine its position in the media market (Charlish & Florkiewicz, 2021; Henley, 2021). A considerable share of both populations therefore consume content that opposes the government’s positions and disinformation. In both countries, these data can be understood as a sign of resilience to disinformation and indeed appear in the existing framework as positive indicators.

More generally, our findings for the Visegrád countries suggest that the framework must be adapted for countries experiencing democratic backsliding. In the original framework, lower trust in the media decreases the values of Czechia and Slovakia but might be understood as contributing to resilience. Conversely, Hungary and Poland display relatively high trust in the media overall, yet the evidence raises concerns about these societies’ institutional resilience to online disinformation. Another important feature of these two democracies is that a massive share of news audiences concentrate on the remaining independent and critical broadcasters, indicating higher resilience. 5

We therefore proposed to advance the existing framework by adding two indicators about the role of civil society and media capture. Arguing that civil society is directly related to a country’s level of disinformation resilience, we chose to include the measure directly. Because media capture does not always correspond to lower trust in the media, we incorporated media capture as an interaction term with media trust, expecting that higher media capture dampens the values of (misleading) high trust in the media. Finally, we contend that the operationalization of populist communication must be adjusted to apply beyond consolidated Western democracies. We discuss our additional measures below, and the full set of sources is presented in Table 3.

Table 1: Additional indicators, data, and sources

|

Additional indices |

Czechia |

Hungary |

Poland |

Slovakia |

Data source |

|

Media capture |

|||||

|

Censorship efforts against the media |

3.05 |

1.97 |

2.16 |

2.60 |

V-Dem (2019) |

|

Online media perspectives |

1.91 |

0.85 |

1.45 |

1.45 |

V-Dem (2019) |

|

Media self-censorship |

3.18 |

1.70 |

2.38 |

3.62 |

V-Dem (2019) |

|

Media bias |

3.22 |

1.97 |

2.67 |

3.71 |

V-Dem (2019) |

|

Critical print/broadcast media |

3.24 |

2.27 |

2.57 |

3.64 |

V-Dem (2019) |

|

Media Capture Index |

0.64 |

0.10 |

0.32 |

0.80 |

V-Dem (2019) |

|

Civil society environment |

|||||

|

CSO entry and exit |

3.34 |

2.17 |

2.79 |

2.81 |

V-Dem (2019) |

|

CSO repression |

3.97 |

2.35 |

2.82 |

0.221 |

V-Dem (2019) |

|

CSO participatory environment |

2.25 |

2.02 |

2.11 |

0.221 |

V-Dem (2019) |

|

Pro-democracy mass mobilization |

3.45 |

1.55 |

3.73 |

0.221 |

V-Dem (2019) |

|

Populist communication |

|||||

|

Vote share of populist parties in 2018 |

48% |

68% |

38% |

37% |

“Votes for Populists”database (2020 |

|

Change in vote share in 2008-2018 |

+35.2 |

+24.2 |

+2.7 |

–13 |

“Votes for Populists”database (2020) |

|

Speeches of political leaders |

0.414 |

0.423 |

0.348 |

0.534 |

Global PopulismDatabase (2022) |

Media capture

Privileged actors, including governments and political elites, frequently seek to manage or suppress information, for instance, by selecting and framing the public agenda, primarily to shape public opinion (Bajomi-Lázár, 2014; Castells, 2013; Curran, 2002; Hallin & Mancini, 2004; Schiffrin, 2018, 2021). Political economists have traditionally defined media capture almost exclusively as direct control over mass media companies (Bagdikian, 2014; Golding & Murdock, 1997). In these accounts, media is described as the most direct socialization factor accessible to elites for delivering their message and manufacturing consent (Herman & Chomsky, 2010).

To include the degree of media capture by political elites, we constructed a new variable called media capture, which conditions the effect of media trust. That is, we interacted these variables in our advanced model. We operationalized media capture using five indicators from the V-Dem database (Coppedge et al., 2024). Censorship efforts measures the level of direct or indirect attempts by the government to censor media output. Online media perspectives captures the diversity of political opinions in domestic online media. Media self-censorship measures the degree of self-censorship among journalists, given that direct suppression is not the only mechanism that can lead to a loss of plurality of opinions. Media bias measures the degree of one-sided standpoints of media outlets against oppositional parties. Critical print / broadcast government measures whether major outlets criticize government activities. For all measures, a higher score signals less attempted media capture. Our combined measure has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > 0.92). The selection of variables is close to the Freedom of Expression and Alternative Sources of Information Index provided by V-Dem.

Civil society

In countries experiencing democratic backsliding, civil society plays a pivotal role in bolstering resilience to both the erosion of democratic accountability (Bernhard, 2020) and online disinformation (Eisen et al., 2019). In terms of democratic governance, civil society organizations monitor online spaces for disinformation aiming to undermine democratic principles (Sakalauskas, 2021; Ufen, 2024) and can offer an avenue for “diagonal accountability,” through which citizens can make their voices heard (Laebens & Lührmann, 2021). Through grassroots activism, advocacy campaigns, and community engagement, civil society organizations can raise awareness about the dangers of online manipulation and provide citizens with tools for critically evaluating information sources (Klečková, 2022; Lewandowsky et al., 2012; Sakalauskas, 2021). Organizations such as the European Citizen Action Service run targeted projects in these countries to foster the creation of civil society coalitions combating disinformation, like the Civil Society Against Disinformation program (European Citizen Action Service, 2023).

The civil society indicator is composed of two variables: the Core Civil Society Index and mobilization for democracy. The Core Civil Society Index captures the scope of civic spaces and activities and gives a measure of how robust a nation’s civil society is. The index comes from the V-Dem database (Coppedge et al., 2019) and is a composite of the organizational environment (including immigration control and the level of state repression) and the level of citizen activism (Lührmann, 2015). Meanwhile, the mobilization for democracy variable measures pro-democratic mass mobilization, which is said to improve institutional capacity against disinformation and has been shown to improve the quality of democracy (Hellmeier & Bernhard, 2022). This variable was operationalized in our study using the question “how frequent and large have events of mass mobilization for pro-democratic aims been?” in the V-Dem database (Coppedge et al., 2019). Our combined indicator had internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > 0.83).

Populist communication

Humprecht et al. (2020) used the Europe-wide Timbro Authoritarian Populism Index (TAP) as their main source for the “vote share of populist parties” and “change in vote share of populist parties” components of the populist communication indicator. While extending the original framework, we identified several limitations of this qualitative measure. In our advancement, we instead rely on the more commonly used measure of populist electoral support, the global Votes for Populists database (Grzymala-Busse & McFaul, 2020), which relies on Mudde’s (2004) definition of populism. Values for Norway were taken from the PopuList 3.0 (Rooduijn et al., 2023; Van Kessel et al., 2023). We left the speeches of political leaders component unchanged.

Our proposed changes did not reduce the internal consistency between the different indices. 6 Having introduced our new measures, we follow Humprecht et al. (2020) and present the correlation matrix for all 20 countries in Table 2.

Table 2: Correlation of indices and exposure to disinformation (advanced framework)

|

Framework indices |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

|||||||

|

Populism (1) |

1 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Polarization (2) |

0.49 |

* |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Media trust (3) |

0.63 |

** |

0.57 |

** |

1 |

||||||||||||

|

Media capture (4) |

0.61 |

** |

0.63 |

** |

0.4 |

1 |

|||||||||||

|

Shared media (5) |

-0.13 |

-0.06 |

0.02 |

-0.31 |

1 |

||||||||||||

|

PSB (6) |

0.45 |

* |

0.49 |

* |

0.46 |

* |

0.37 |

-0.16 |

1 |

||||||||

|

Social media (7) |

0.51 |

* |

0.44 |

0.51 |

* |

0.53 |

* |

-0.2 |

0.62 |

** |

1 |

||||||

|

Market size (8) |

-0.09 |

0.4 |

0.08 |

-0.06 |

0.07 |

-0.15 |

-0.41 |

1 |

|||||||||

|

Civil society (8) |

0.13 |

0.31 |

-0.08 |

0.70 |

*** |

-0.26 |

0.24 |

0.14 |

-0.11 |

1 |

|||||||

|

Resilience to disinfo (10) |

-0.69 |

*** |

-0.56 |

* |

-0.71 |

*** |

-0.72 |

*** |

0.28 |

-0.57 |

** |

-0.84 |

*** |

0.22 |

-0.19 |

1 |

Note: N = 20. Values are Pearson’s correlation coefficients. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p<.001. PSB = public service broadcasting.

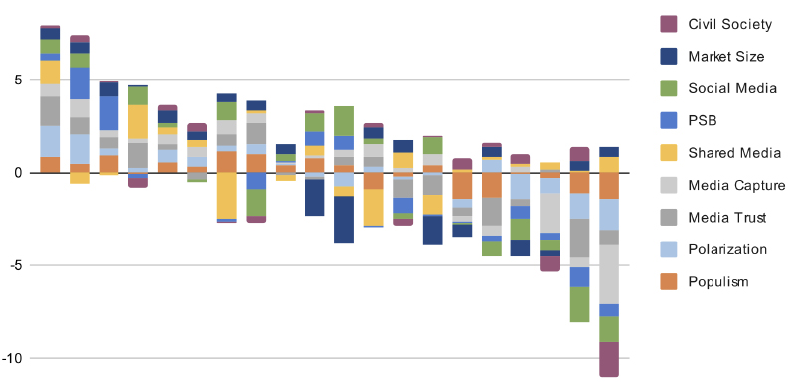

Next, we applied our advanced framework, presenting the results in Figure 2. The addition of media capture and civil society had important consequences in the Visegrád countries, moving them towards the bottom of the sample. Our advanced framework positions these countries as less resilient to disinformation, except for Slovakia. Hungary now scores at the lowest end of all countries. Poland and Czechia are negatively affected by the inclusion of these new variables, whereas Slovakia’s position remains largely the same.

Figure 2: Resilience indicators (advanced framework)

Note: Standardized index values. Higher values represent higher performance on the resilience indicators.

The inclusion of the Media Capture Index attenuated the otherwise positive value of media trust in Poland. In Czechia, lower rates of polarization and strong public service broadcasting (PSB) and civil society contributed to higher resilience than in some neighboring states. Yet, higher degrees of populism, lower trust in news media, and more widespread use of social media for news consumption contributed to the country’s vulnerabilities in this framework. Hungary scored the lowest of our 18 countries, only performing positively on shared media and market size. Slovakia was the best performing of the Visegrád group, performing in the middle of the countries due to its higher trust in news media and large consumption of shared media outlets. Hungary and Poland demonstrated strong degrees of media capture, Czechia some degree of media capture, and only Slovakia scored positively in this area. Our civil society indicator was also strongly negative for Hungary and Poland, highly positive for Czechia, and slightly negative for Slovakia.

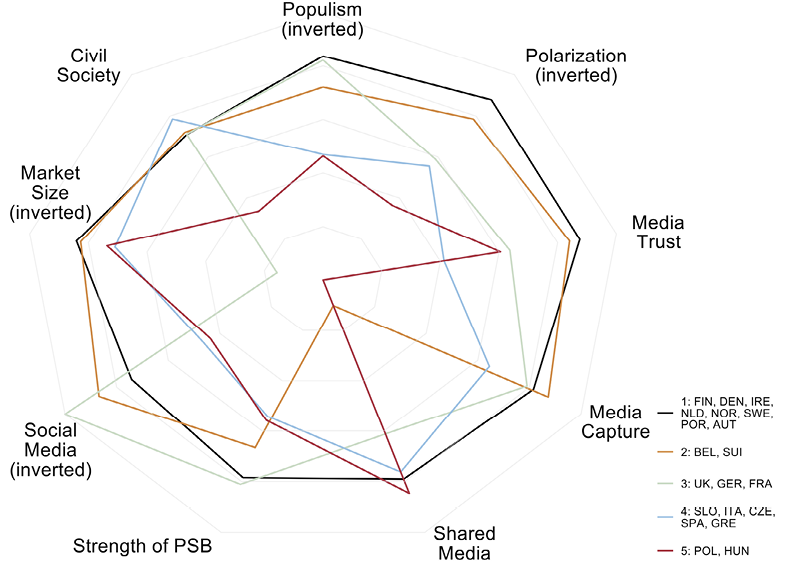

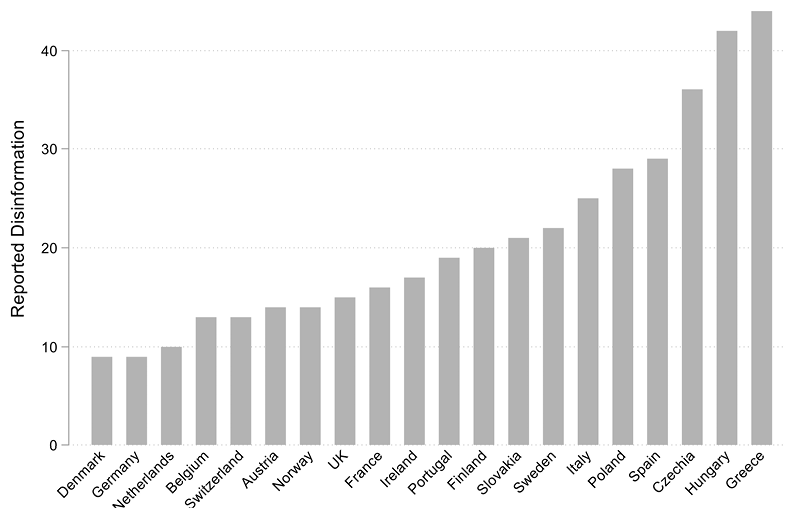

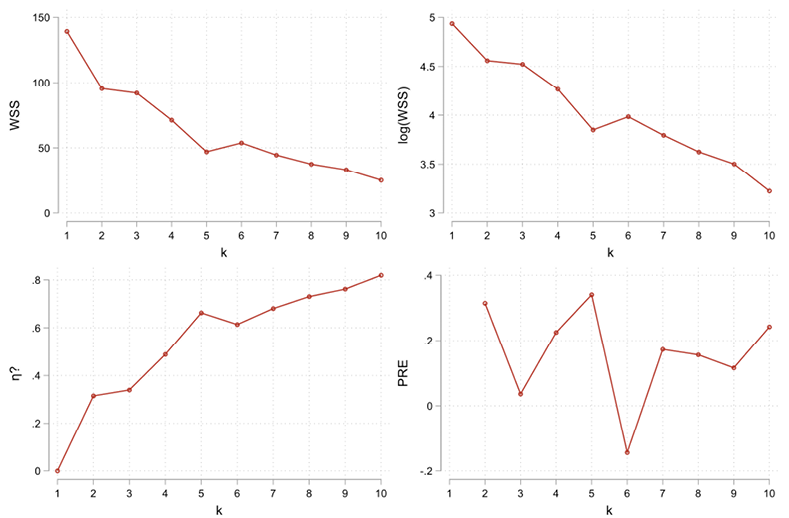

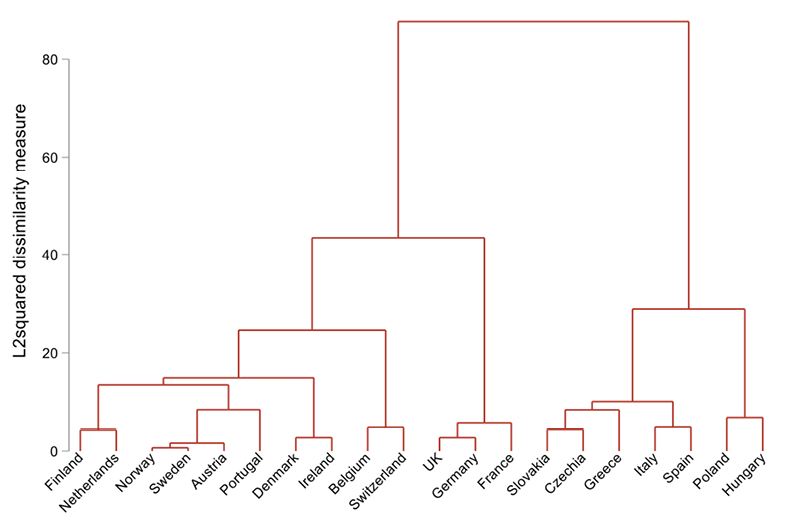

Following Humprecht et al. (2020), we next performed a hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s algorithm and the squared Euclidean distance as a heterogeneity measure. This approach led us to choose a five-cluster solution as opposed to Humprecht et al.’s (2020) three-cluster solution, with a strong elbow in our scree plots at the fifth clusters. 7 Figure 3 visualizes the country means for each cluster across the nine indicators in our advanced model.

Figure 3: Cluster Country Means

Clusters 1-3 broadly align with Humprecht et al.’s (2020) “media-supportive” cluster. Our Cluster 1, which consists of Finland, Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Portugal, and Austria, is very similar to this cluster. 8 Cluster 2, containing Belgium and Switzerland, is distinct from Cluster 1 only in terms of its lower levels of shared media, likely due to the lack of a single common language in these countries. Our Cluster 3, comprising the United Kingdom, Germany, and France, differs from Cluster 1 in terms of market size. As Humprecht et al. (2020) note in their limitations section, the inclusion of the United States in their study makes differences in the size of the European countries’ markets negligible, a distinction revealed in our European-focused analysis.

Of greater interest for our study is the positioning of the Visegrád countries in Clusters 4 and 5. Slovakia and Czechia were positioned in Cluster 4, Humprecht et al.’s (2020) “polarized” cluster, alongside Italy, Spain, and Greece. Conversely, Poland and Hungary were positioned in their own cluster (Cluster 5). The biggest difference between Clusters 4 and 5, and the reason for positioning Poland and Hungary outside of the “polarized” cluster, is their much weaker civil society and media capture scores. In the indices from the original framework, these countries did not appear to be very different. Yet, the addition of our advancements resulted in these countries being put in different clusters for their overall resilience to disinformation, underscoring the importance of our additional indices for comparing countries experiencing democratic backsliding.

Having demonstrated the descriptive patterns of these different indicators in line with the original study, we once again followed Humprecht et al. (2020) by applying ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions on the framework indices and online disinformation. In Table 3, we present the results using the original framework (1) and our advanced framework (2), extending the sample to include the four Visegrád countries in both cases. As in the original study, the indices explained a large proportion (R2 = 0.858) of the variance in the level of exposure to disinformation in the replication of the original model (1). However, we also note some differences from the original study, with no significant associations for market size or media trust. The lack of association with market size is likely due to the focus on European countries given the disproportionate market size of the United States in the original study, whereas the lack of association with media trust is likely connected to our addition of the Visegrád countries, which points to the relevance of our hypothesized advancements.

Table 3: Regression results

|

Disinformation exposure |

||

|

Original (1) |

Advanced (2) |

|

|

Populist communication |

-0.227 |

0.124 |

|

(0.185) |

(0.156) |

|

|

Societal polarization |

-0.090 |

0.124 |

|

(0.219) |

(0.181) |

|

|

Media trust |

-0.315 |

-0.302* |

|

(0.159) |

(0.123) |

|

|

Media capture |

-0.589* |

|

|

(0.209) |

||

|

Media trust x mediacapture |

0.365* |

|

|

(0.144) |

||

|

Strength of PSB |

0.074 |

-0.198 |

|

(0.191) |

(0.154) |

|

|

Shared media |

0.125 |

0.065 |

|

(0.116) |

(0.085) |

|

|

Size of onlinemedia market |

0.044 |

-0.066 |

|

(0.176) |

(0.136) |

|

|

Social media newsconsumption |

-0.556* |

-0.368 |

|

(0.205) |

(0.066) |

|

|

Civil society |

0.602 |

|

|

(0.275) |

||

|

Observations |

20 |

20 |

|

R2 |

0.858 |

0.950 |

|

Adjusted R2 |

0.776 |

0.894 |

|

Residual std. error |

0.473 |

0.326 |

|

10.396 *** |

16.998*** |

|

|

F statistic |

(df = 7; 12) |

(df = 10; 9) |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p<.001

Our advanced model (2) explains more of this variation (R2 = 0.950), suggesting that our additional theoretical dimensions improved our understanding of exposure to disinformation. In particular, the interaction of media trust with media capture made both variables more significant in predicting the level of exposure to disinformation. Adding media capture to the framework revealed significant negative associations between both media trust and media capture and countries’ resilience to disinformation. Yet, we also note a positive effect of the interaction term, indicating that the that the negative effects of media trust and media capture are conditional on each other, with the negative impact of media trust become less severe as media capture increases and the negative effect of media capture weakening at higher levels of media trust. Civil society was not significantly predictive of exposure to disinformation.

6 Discussion and Conclusion

Our study builds on the framework developed by Humprecht et al. (2020), extending its application from consolidated Western democracies to four countries experiencing democratic backsliding – the Visegrád Group. In doing so, we contribute to the broader understanding of societal resilience to disinformation. Specifically, our inclusion of the media capture and civil society indicators helps contextualize resilience in backsliding democracies. These additions advance the original model by accounting for how institutional erosion and grassroots civic activity influence societal capacities to resist disinformation and make the original framework applicable to a broader range of political contexts, including those marked by democratic backsliding.

In our empirical application, Slovakia and Czechia were clustered alongside southern European countries such as Spain, Italy, and Greece in the “polarized” cluster. Slovakia was the most resilient of the Visegrád countries in this period (up to 2020). Yet, this study was conducted against the backdrop of new threats posed by the Fico government. Slovakian citizens previously paid the lowest license fee in Europe (Botiková, 2020), but the license fee was abolished in 2023 (“Viewer Licence Fees to Be Scrapped,” 2023), and the public broadcasting service RTVS, deemed the most objective news source by Slovakians, was closed by the government and replaced with a new broadcaster in 2024 (Fabok, 2024). Meanwhile, Czechia demonstrated a stronger PSB and lower polarization than its neighbors. Since Babiš left office, the new government, led by Petr Fiala, has introduced amendments to improve independence in the media market by building safeguards, notably eliminating politicians’ control over the composition of boards and automatically raising the license fee in line with inflation (Daniels, 2022). 9 Despite these positive steps, the threat of authoritarian populism in Czechia remains as ANO continues to be one of the dominant parties in the country.

Poland and Hungary were sufficiently different on the dimensions of media capture and civil society to warrant their own cluster in our empirical analysis. Poland’s means of propaganda appear to have been so effective that trust in the media overall cannot simply be taken as a sign of resilience. The same pattern holds for Hungary, with multiple indicators performing badly enough to distinguish these countries from the polarized cluster. Both governments have profited from disinformation and conspiracy narratives by concentrating media power and inducing fear among public critics of their governmental ideologies and tools. In this regard, the new Polish government’s reestablishment of the independence of the PSB appears to be an important first step towards improving the situation (Wójcik, 2023).

One important contribution of this study is the contextual relevance of media trust in relation to media capture. Although high trust in the media is generally considered a positive indicator of resilience in consolidated democracies, our findings challenge this assumption in contexts where media systems are heavily politicized or captured by authoritarian actors. In Hungary and Poland, for instance, trust in the media does not indicate resilience but vulnerability to disinformation aligned with government propaganda. Media capture by political elites undermines democratic deliberation and enables the manipulation of public opinion in consolidated and backsliding democracies alike (Schiffrin, 2021). The importance of media trust is conditioned by the degree of institutional capture of media by political actors, where a combination of high levels of media trust and media capture aligns with higher levels of disinformation exposure. In short, the capture of trusted media sources by political elites seems to be a recipe for disinformation disaster regardless of the democratic context in which it occurs. Therefore, by incorporating media capture, we offer an improved framework for evaluating the complex relationship between media systems and societal resilience.

Further, the inclusion of civil society in our advanced framework highlights the role of non-state actors in mitigating the impact of disinformation, particularly in environments where formal democratic institutions are weakened. Although the space for civil society is greatest in the most consolidated democracies, pro-democratic mobilization is more visible in the Visegrád group, which suggests that societies react to threats of democratic backsliding with awareness and by building capacities to inform and mobilize others. Where state institutions fail to reduce the dissemination of disinformation, these networks and alternative information providers become crucial sources in the fight against disinformation. A growing number of organizations in the Visegrád countries are already dedicated to these activities (Syrovátka, 2021). Instances of civil society resistance against disinformation include the “Czechian elves,” a societal organized group that counters disinformation by Russian bots (Filipec, 2019). As seen across the Visegrád countries, these groups can help support information flow outside of captured professional media.

More broadly, civil society organizations can disseminate independent information and help mobilize democratic resistance (Bernhard, 2020; Eisen et al., 2019). Pro-democratic mobilization in civil society can counterbalance institutional deficiencies as strong civic engagement enhances resilience despite structural vulnerabilities. This finding aligns with broader theories of democratic resilience, which contend that bottom-up efforts can complement or even substitute for institutional safeguards by providing accountability during periods of democratic decline (Laebens & Lührmann, 2021). Pro-democratic mobilization can act as a resource for resilience to disinformation. Still, the question remains of whether and to what extent civil society mobilization is actually impactful against the spread of disinformation.

Our approach also contributes to comparative political research by demonstrating the necessity of adapting theoretical models to different contexts. While Humprecht et al.’s (2020) framework identifies structural factors influencing resilience to disinformation in consolidated democracies, its direct application to backsliding democracies would risk misinterpreting key indicators. The interaction between media trust and media capture highlights how the same variable can have distinct implications depending on the political and media environment and points out the importance of considering local political, social, and historical dynamics to understand disinformation (see, e.g., Pasitselska, 2022). With this work, we hope to offer a theoretical advance for future research on resilience in different settings.

We also contribute to ongoing theoretical debates about the relationship between disinformation and democratic backsliding. Disinformation campaigns exploit and exacerbate existing societal divisions and often serve as tools for authoritarian regimes to consolidate their power and undermine the opposition (Humprecht et al., 2023). Our media capture and civil society engagement measures suggest pathways for strengthening resilience in vulnerable democracies, which will likely continue to be particularly relevant as disinformation challenges democratic norms globally, including in consolidated democracies (see, e.g., Norris & Inglehart, 2019).

Although our extension of Humprecht et al.’s (2020) model offers insight into resilience to disinformation in countries experiencing democratic backsliding, it has several limitations. As in the original study, one limitation is the reliance on macro-level indicators that are unlikely to capture the nuances of individual behaviors and perceptions, such as personal experiences with disinformation or varying levels of media literacy. While our indicators provide an overarching comparative analysis, they may overlook the influence of cultural, historical, and institutional idiosyncrasies that influence individuals’ behaviors. Following Humprecht et al. (2020, p. 510), we note that some components of the indicators are volatile, meaning that their values are connected to the time when they were collected. Further, our dependent variable, perception of exposure to disinformation, serves as an indirect – and potentially unreliable – proxy for the actual prevalence of disinformation within a country.

Applying a framework designed for consolidated democracies to countries experiencing democratic backsliding presents inherent challenges. Our inclusion of the Media Capture Index and Civil Society Index also introduces methodological constraints. For example, the interaction of media trust with media capture highlights critical dynamics in the Visegrád countries but assumes consistent interpretations of media capture across contexts. In countries with high levels of government interference, our measures may underrepresent the complexity of media environments or fail to capture informal mechanisms of control.

Finally, our study’s cross-sectional design limits its ability to capture changes in disinformation resilience over time. Democratic backsliding is a dynamic process, and the political and media structures in the Visegrád countries have experienced rapid shifts in recent years. Future studies using panel data would therefore help us understand how resilience evolves in response to changing political and media environments.

Lastly, our study highlights the need to consider additional communicative contexts when thinking about disinformation in countries other than consolidated democracies. In doing so, we identified distinct components that also help us understand societal resilience to disinformation in countries that are not experiencing democratic backsliding. As countries that have long been considered democracies experience society-wide challenges around disinformation and democratic erosion, it may become increasingly necessary to learn how these challenges manifest around the world.

References

Aalberg, T., & Cushion, S. (2016, August 5). Public service broadcasting, hard news, and citizens’ knowledge of current affairs. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.38

Aalberg, T., Papathanassopoulos, S., Soroka, S., Curran, J., Hayashi, K., Iyengar, S., Jones, P. K., Mazzoleni, G., Rojas, H., Rowe, D., & Tiffen, R. (2013). International TV news, foreign affairs interest, and public knowledge. Journalism Studies, 14(3), 387-406. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2013.765636

Alyukov, M. (2023). Harnessing distrust: News, credibility heuristics, and war in an authoritarian regime. Political Communication, 40(5), 527-554. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2023.2196951

Ash, T. G. (2024, January 23). The world should learn from Poland’s tragedy: Restoring democracy is even harder than creating it. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/jan/23/poland-restoring-democracy-harder-donald-tusk

Bagdikian, B. H. (2014). The new media monopoly: A completely revised and updated edition with seven new chapters. Beacon Press.

Bajomi-Lázár, P. (2014). Party colonisation of the media in Central and Eastern Europe. Central European University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7829/j.ctt1287c19

Bakke, E., & Sitter, N. (2021). Each unhappy in its own way? The rise and fall of social democracy in the Visegrád countries since 1989. In N. Brandal, Ø. Bratberg, & D. E. Thorsen (Eds.), Social democracy in the 21st century (Vol. 35, pp. 37-68). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0195-631020210000035003

Bátorfy, A., & Urbán, Á. (2020). State advertising as an instrument of transformation of the media market in Hungary. East European Politics, 36(1), 44-65. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2019.1662398

Bede, M. (2018). Amid media takeover, Hungary’s largest TV station proves “tough nut” to crack: Foreign ownership no guarantee of protection for RTL Klub. Newsroom. https://ipi.media/amid-media-takeover-hungarys-largest-tv-station-proves-tough-nut-to-crack/

Bernhard, M. (2020). What do we know about civil society and regime change thirty years after 1989? East European Politics, 36(3), 341-362. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2020.1787160

Bernhard, M., Guasti, P., & Bustikova, L. (2019, July). Czech protesters are trying to defend democracy, 30 years after the Velvet Revolution. Can they succeed? Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/07/16/czech-protesters-are-trying-defend-democracy-years-after-velvet-revolution-can-they-succeed/

Bokša, M. (2019). Russian information warfare in Central and Eastern Europe: Strategies, impact, countermeasures. German Marshall Fund. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep21238

Botiková, Z. (2020, August). New financing of public broadcasting discussed. Rádio Slovakia International. https://enrsi.rtvs.sk/articles/Culture/231056/new-financing-of-public-broadcasting-discussed

Brüggemann, M., Engesser, S., Büchel, F., Humprecht, E., & Castro, L. (2014). Hallin and Mancini revisited: Four empirical types of Western media systems. Journal of Communication, 64(6), 1037-1065. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12127

Burčík, M. (2019, April). Six people involved in the surveillance of journalists, Kočner paid thousands: People who followed journalists for Kočner are trying to rid themselves of guilt. Slovak Spectator. https://spectator.sme.sk/c/22105666/screening-journalists-monitoring-kocner-kriak-police-toth.html

Buštíková, L. (2021). Nations in transit 2021 Czech Republic: Country report. Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/czech-republic/nations-transit/2021

Cabada, L. (2022). Russian aggression against Ukraine as the accelerator in the systemic struggle against disinformation in Czechia. Applied Cybersecurity & Internet Governance, 1(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0016.0916

Castells, M. (2013). Communication power (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Chaisty, P., & Whitefield, S. (2022). Stalin in contemporary Russia: Admired and required. OSW Centre for Eastern Studies. https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2017-10-31/stalin-contemporary-russia-admired-and-required

Chappell, L. (2021). Polish foreign policy: From ‘go to’ player to territorial defender. In J. K. Joly & T. Haesebrouck (Eds.), Foreign policy change in Europe since 1991 (pp. 233-258). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68218-7_10

Charlish, A., & Florkiewicz, P. (2021, July 8). Polish draft law threatens U.S.-owned broadcaster, opposition says. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/polish-draft-law-threatens-us-owned-broadcaster-opposition-says-2021-07-08/

Chastard, J.-B. (2024, July 6). Slovakia undertakes purging of power within institutions. Le Monde. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2024/07/06/slovakia-undertakes-purging-of-power-within-institutions_6676878_4.html

Cianetti, L., & Hanley, S. (2021). The end of the backsliding paradigm. Journal of Democracy, 32(1), 66-80. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2021.0001

Cipers, S., Meyer, T., & Lefevere, J. (2023). Government responses to online disinformation unpacked. Internet Policy Review, 12(4). https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/government-responses-to-online-disinformation-unpacked

Čižik, T., & Masariková, M. (2018). Cultural identity as a tool of Russian information warfare: Examples from Slovakia. Science & Military, 13(1), 11-16.

Colomina, C., Sánchez Margalef, H., Youngs, R., & Jones, K. (2021). The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world: Study requested by the DROI Subcommittee. European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/653635/EXPO_STU(2021)653635_EN.pdf

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., et al. (2019). V-Dem Dataset V9. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://www.v-dem.net/data/dataset-archive/

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Angiolillo, F., Bernhard, M., Borella, C., Cornell, A., Fish, M. S., Fox, L., Gastaldi, L., Gjerlow, H., Glynn, A., Good God, A., Grahn, S., Hicken, A., Kinzelbach, K., … Ziblatt, D. (2024). V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v14. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://doi.org/10.23696/mcwt-fr58

Curran, J. (2002). Media and power. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203417744

Daniels, D. (2022, June 9). Focus on: The future of the Czech Republic’s public media. Public Media Alliance. https://www.publicmediaalliance.org/focus-on-the-future-of-czech-republics-public-media/

Diaz Ruiz, C., & Nilsson, T. (2023). Disinformation and echo chambers: How disinformation circulates on social media through identity-driven controversies. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 42(1), 18-35.https://doi.org/10.1177/07439156221103852

Einstein, K. L., & Glick, D. M. (2015). Do I think BLS data are BS? The consequences of conspiracy theories. Political Behavior, 37(3), 679-701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-014-9287-z

Eisen, N., Kenealy, A., Corke, S., Taussig, T., & Polyakova, A. (2019). The democracy playbook: Preventing and reversing democratic backsliding. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/The-Democracy-Playbook_Preventing-and-Reversing-Democratic-Backsliding.pdf

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51-58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

European Citizen Action Service. (2023). Civil society against disinformation. ECAS. https://ecas.org/projects/civil-society-against-disinformation/

Fabok, M. (2024, June 20). Parliament okays creation of Slovak television and radio. NewsNow. https://newsnow.tasr.sk/parliament-okays-creation-of-slovak-television-and-radio/

Fallis, D. (2015). What is disinformation? Library Trends, 63(3), 401-426. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2015.0014

Filipec, O. (2019). Building an information resilient society: An organic approach. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 11(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v11.i1.6065

Fillipov, G. (2020). Nations in transit 2020 Hungary: Country report. Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/hungary/nations-transit/2020

Fletcher, R., & Nielsen, R. K. (2017). Are news audiences increasingly fragmented? A cross-national comparative analysis of cross-platform news audience fragmentation and duplication. Journal of Communication, 67(4), 476-498. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12315

Freelon, D., & Wells, C. (2020). Disinformation as political communication. Political Communication, 37(2), 145-156.

Gluchman, V. (2011). Professional ethics of politicians in Slovakia. Ethics and Bioethics (in Central Europe), 1(1-2), 39-50.

Goh, D. (2015). Narrowing the knowledge gap: The role of alternative online media in an authoritarian press system. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 92(4), 877-897. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699015596336

Golding, P., & Murdock, G. (1997). The political economy of the media. Edward Elgar.

Gorwa, R. (2017). Computational propaganda in Poland: False amplifiers and the digital public sphere (Computational Propaganda Research Project Working Paper No. 2017.4). University of Oxford. https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2017/06/Comprop-Poland.pdf

Grabbe, H. (2006). The EU’s transformative power: Europeanization through conditionality in Central and Eastern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan.

Griffen, S. (2020). Hungary: A lesson in media control. British Journalism Review, 31(1), 57-62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956474820910071

Grzymala-Busse, A., & McFaul, M. (2020). “Votes for populists” database. Global Populisms Project: Stanford University. https://fsi.stanford.edu/global-populisms/content/vote-populists

Haglund, D. G., Schulze, J. L., & Vangelov, O. (2022). Hungary’s slide toward autocracy: Domestic and external impediments to locking in democratic reforms. Political Science Quarterly, 137(4), 675-713. https://doi.org/10.1002/polq.13416

Hajdu, D., Klingová, K., & Sawiris, M. (2021). Vulnerability index 2021: Slovakia: Country report. Globesec, Centre for Democracy and Resilience. https://vulnerabilityindex.org/slovakia.html

Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511790867

Hameleers, M. (2023). This is clearly fake! Mis- and disinformation beliefs and the (accurate) recognition of pseudo-information – Evidence from the United States and the Netherlands. American Behavioral Scientist, 68(10), 1249-1268. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642231174334

Hameleers, M., & Minihold, S. (2022). Constructing discourses on (un)truthfulness: Attributions of reality, misinformation, and disinformation by politicians in a comparative social media setting. Communication Research, 49(8), 1176-1199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220982762

Hanitzsch, T., Van Dalen, A., & Steindl, N. (2018). Caught in the nexus: A comparative and longitudinal analysis of public trust in the press. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(1), 3-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217740695

Hanley, S., & Vachudova, M. A. (2019). Understanding the illiberal turn: Democratic backsliding in the Czech Republic. In L. Cianetti, J. Sawson, & S. Hanley (Eds.), Rethinking “democratic backsliding” in Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 34-54). Routledge.

Hawkins, K. A., Aguilar, R., Silva, B. C., Jenne, E. K., Kocijan, B., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2022). Global populism database. Harvard Dataverse. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LFTQEZ

Heissler, J. (2018). Why the Czechs are nostalgic about Russia. Heinrich Böll Stiftung. https://us.boell.org/en/2018/07/12/why-czechs-are-nostalgic-about-russia

Hellmeier, S., & Bernhard, M. (2022). Mass mobilization and regime change. Evidence from a new measure of mobilization for democracy and autocracy from 1900 to 2020. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4019439

Henley, J. (2021, August 11). Polish parliament passes controversial new media ownership bill. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/11/poland-coalition-under-threat-as-parliament-votes-on-controversial-media-bill

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (2010). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. Vintage Digital.

Hlatky, R. (2023). Slovakia: Nations in transit 2023 country report. Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/slovakia/nations-transit/2023

Hornat, J. (2021). External and internal factors shaping the substance of Visegrad states’ democracy assistance. In J. Hornat (Ed.), The Visegrad group and democracy promotion: Transition experience and beyond (pp. 103-133). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78188-0_6

Humprecht, E., Esser, F., & van Aelst, P. (2020). Resilience to online disinformation: A framework for cross-national comparative research. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(3), 493-516.

Humprecht, E., Esser, F., van Aelst, P., Staender, A., & Morosoli, S. (2023). The sharing of disinformation in cross-national comparison: Analyzing patterns of resilience. Information, Communication & Society, 26(7), 1342-1362.

International Telecommunication Union & World Bank. (2021). Individuals using the internet (% of population): World telecommunication/ICT indicators database. World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?end=2021&start=1960&view=chart

Jolley, D., & Douglas, K. M. (2014). The social consequences of conspiracism: Exposure to conspiracy theories decreases intentions to engage in politics and to reduce one’s carbon footprint. British Journal of Psychology, 105(1), 35-56. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12018

Kalogeropoulos, A., Newman, N., & Fletcher, R. (2018). Reuters Institute digital news report. University of Oxford. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/digital-news-report-2018.pdf

Klečková, A. (2022). The role of cyber “elves” against Russian information operations. German Marshall Fund of the United States.

Krekó, P., & Enyedi, Z. (2018). Explaining Eastern Europe: Orbán’s laboratory of illiberalism. Journal of Democracy, 29(3), 39-51.

Köles, P., Dubóczi, P., Ružičková, M., Hasáková, M. A., Mamuladze, N., Lachashvili, I., Naroushvili, D., & Tsitsikashvil, M. (2021). Analysis of disinformation narratives: In the context of the 2020 parliamentary elections in Slovakia and Georgia. Slovak Security Policy Institute and Georgia’s Reforms Associates. https://slovaksecurity.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Analysis-of-Disinformation-Narratives.pdf

Ladd, J. M. (2010). The role of media distrust in partisan voting. Political Behavior, 32(4), 567-585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9123-z

Laebens, M. G., & Lührmann, A. (2021). What halts democratic erosion? The changing role of accountability. Democratization, 28(5), 908-928. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1897109

Lamont, M., & Hall, P. A. (Eds.). (2013). Social resilience in the neoliberal era. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139542425

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest: A Journal of the American Psychological Society, 13(3), 106-131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612451018

Lührmann, A. (2015). Civil society and political parties revisited (V-Dem Policy Brief). V-Dem. https://v-dem.net/media/publications/v-dem_policybrief_2_2015.pdf

Maati, A., Edel, M., Saglam, K., Schlumberger, O., & Sirikupt, C. (2023). Information, doubt, and democracy: How digitization spurs democratic decay. Democratization, 0(0), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2023.2234831

Masket, S., & Noel, H. (2021). Political parties. W. W. Norton & Company.

Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. University of Chicago Press.

McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176-187.

Mesežnikov, G., & Gyárfášová, O. (2018). Explaining Eastern Europe: Slovakia’s conflicting camps. Journal of Democracy, 29(3), 78-90.

Mokrá, L., & Kováčiková, H. (2023). The future of Slovakia and its relation to the European Union: From adopting to shaping EU policies. Comparative Southeast European Studies, 71(3), 357-387. https://doi.org/10.1515/soeu-2022-0053

Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541-563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C., Eddy, K., & Nielsen, R. K. (2022). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2022. Reuters Institute. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/Digital_News-Report_2022.pdf

Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108595841

OECD. (2022). Building trust and reinforcing democracy: Preparing the ground for government action. OECD Publishing.

Pasitselska, O. (2022). Better ask your neighbor: Renegotiating media trust during the Russian–Ukrainian conflict. Human Communication Research, 48(2), 179-202. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqac003

Pathak, A., Srihari, R. K., & Natu, N. (2021). Disinformation: Analysis and identification. Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, 27(3), 357-375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10588-021-09336-x

Pjesivac, I., Spasovska, K., & Imre, I. (2016). The truth between the lines: Conceptualization of trust in news media in Serbia, Macedonia, and Croatia. Mass Communication and Society, 19(3), 323-351. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2015.1128548

Popiołek, M., Hapek, M., & Barańska, M. (2021). Infodemia – an analysis of fake news in Polish news portals and traditional media during the coronavirus pandemic. Communication & Society, 34(4), 81-98. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.34.4.81-98

Ptak, A. (2023, May 4). Poland moves up in World Press Freedom Index for the first time in eight years but issues remain. Notes From Poland.https://notesfrompoland.com/2023/05/04/poland-moves-up-in-world-press-freedom-index-for-the-first-time-in-eight-years-but-issues-remain/

Reisher, J. (2022). The effect of disinformation on democracy: The impact of Hungary’s democratic decline. CES Working Papers, XIV(1), 42-68.

Reporters Without Borders. (2023). World press freedom index. RSF. https://rsf.org/en/index

Rooduijn, M., Pirro, A. L. P., Halikiopoulou, D., Froio, C., Van Kessel, S., De Lange, S. L., Mudde, C., & Taggart, P. (2023). The PopuList: A database of populist, far-left, and far-right parties using expert-informed qualitative comparative classification (EiQCC). British Journal of Political Science, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123423000431

Rosińska, K. A. (2021). Disinformation in Poland: Thematic classification based on content analysis of fake news from 2019. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 15(4), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2021-4-5

Sakalauskas, G. (2021). Elves vs trolls. In S. Jayakumar, B. Ang, & N. D. Anwar (Eds.), Disinformation and fake news (pp. 131-136). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-5876-4_10

Schiffrin, A. (2018). Introduction to special issue on media capture. Journalism, 19(8), 1033-1042. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917725167

Schiffrin, A. (2021). Media capture: How money, digital platforms, and governments control the news. Columbia University Press.

Schleffer, G., & Miller, B. (2021). The political effects of social media platforms on different regime types. Texas National Security Review, 4(3), 78-103.

Schütz, M., & Bull, F. R. (2017). Unverstandene Union: Eine organisationswissenschaftliche analyse der EU. Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-17149-0

Serrano-Puche, J. (2021). Digital disinformation and emotions: Exploring the social risks of affective polarization. International Review of Sociology, 31(2), 231-245. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2021.1947953

Škarba, T., & Višňovský, J. (2023). Pro-Russian propaganda on social media during the pre-election campaign in Slovakia. In The International Conference on Social Sciences NORDSCI (Vol. 6). https://doi.org/10.32008/NORDSCI2023/B1/V6

Somer, M., McCoy, J. L., & Luke, R. E. (2021). Pernicious polarization, autocratization, and opposition strategies. Democratization, 28(5), 929-948. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1865316

Spies, S. (2019). Defining “disinformation.” MediaWell. https://mediawell.ssrc.org/?post_type=ssrc_lit_review&p=52263

Štětka, V. (2015). The rise of oligarchs as media owners. In J. Zielonka (Ed.), Media and politics in new democracies (pp. 85-98). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198747536.003.0006

Štětka, V., & Mihelj, S. (2024). The illiberal public sphere: Media in polarized societies. Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-54489-7

Stiglitz, J. E., & Kosenko, A. (2024). The economics of information in a world of disinformation: A survey part 1: Indirect communication (Working Paper No. 32049). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w32049

Stoklasa, R. (2023, December 19). Thousands of Slovaks continue protesting government’s criminal law reforms. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/thousands-slovaks-continue-protesting-governments-criminal-law-reforms-2023-12-19/

Sybera, A. (2022). Nations in transit 2022 Czech Republic: Country report. Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/czech-republic/nations-transit/2022

Syrovátka, J. (2021). Civil society initiatives tackling disinformation: Experiences of Central European countries. In M. Gregor & P. Mlejnková (Eds.), Challenging online propaganda and disinformation in the 21st century (pp. 225-253). Springer International Publishing.

Szicherle, P., & Molnár, C. (2021). Vulnerability index 2021: Hungary: Country report. In D. Hajdu, K. Klingová, & M. Sawiris (Eds.), Globesec, Centre for Democracy and Resilience. https://www.globsec.org/what-we-do/publications/globsec-vulnerability-index-evaluating-susceptibility-foreign-malign

Szostek, J. (2018). News media repertoires and strategic narrative reception: A paradox of dis/belief in authoritarian Russia. New Media & Society, 20(1), 68-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816656638

Tenove, C. (2020). Protecting democracy from disinformation: Normative threats and policy responses. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(3), 517-537. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220918740

Tucker, J., Guess, A., Barbera, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A review of the scientific literature. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3144139

Turcilo, L., & Obrenovic, M. (2020). Misinformation, disinformation, malinformation: Causes, trends, and their influence on democracy. Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

Ufen, A. (2024). The rise of digital repression in Indonesia under Joko Widodo. GIGA Focus, 1. https://doi.org/10.57671/gfas-24012

Urbán, Á., Polyák, G., & Horváth, K. (2023). How public service media disinformation shapes Hungarian public discourse. Media and Communication, 11(4), 62-72. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i4.7148

Urbániková, M., & Haniková, L. (2024). Coping with the murder: The impact of Ján Kuciak’s assassination on Slovak investigative journalists. In O. Westlund, R. Krøvel, & K. S. Orgeret (Eds.), Journalism and Safety: An Introduction to the Field (pp. 285-305). Routledge. https://www.muni.cz/en/research/publications/2390500

Van Kessel, S., De Lange, S., Taggart, P., Rooduijn, M., Halikiopoulou, D., Pirro, A., Froio, C., & Mudde, C. (2023). The PopuList 3.0. OSF. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2EWKQ

Végh, Z. (2022). Nations in transit 2022 Hungary: Country report. Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/hungary/nations-transit/2023

“Viewer licence fees to be scrapped – Culture – Rádio RSI English – STVR.” (2023). Rtvs.sk. https://enrsi.rtvs.sk/articles/Culture/317680/viewer-licence-fees-to-be-scrapped

Waisbord, S. (2018). The elective affinity between post-truth communication and populist politics. Communication Research and Practice, 4(1), 17-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2018.1428928

Waisová, Š. (2020). Central Europe in the new millennium: The new great game? US, Russian and Chinese interests and activities in Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia. UNISCI Journal, 53, 25-42.

Walker, S. (2022, January 28). Hungarian journalists targeted with Pegasus spyware to sue state. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/28/hungarian-journalists-targeted-with-pegasus-spyware-to-sue-state

Wenzel, M., Stasiuk-Krajewska, K., Macková, V., & Turková, K. (2023). The penetration of Russian disinformation related to the war in Ukraine: Evidence from Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia. International Political Science Review, 45(2), pp. 192-208. https://doi.org/10.1177/01925121231205259

West, D. M. (2017). How to combat fake news and disinformation. Center for Technology Innovation: Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-to-combat-fake-news-and-disinformation/

Wikforss, Å. (2023). The dangers of disinformation. In H. Samaržija & Q. Cassam (Eds.), The epistemology of democracy (pp. 90-112). Routledge.

Witkowski, P. (2023). Intermarium or Hyperborea? Pan-Slavism in Poland after 1989. In M. Suslov, M. Čejka, & V. Ðorđević (Eds.), Pan-Slavism and Slavophilia in contemporary Central and Eastern Europe: Origins, manifestations and functions (pp. 155-181). Springer International Publishing.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17875-7_9

Wójcik, A. (2023, October). Restoring Poland’s media freedom. Verfassungsblog. https://verfassungsblog.de/restoring-polands-media-freedom/

Wójcik, A., & Wiatrowski, M. (2022). Nations in transit 2022: Poland: Country report. Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/poland/nations-transit/2022

Woolley, S. C., & Guilbeault, D. (2017). Computational propaganda in the United States of America: Manufacturing consensus online (Working Paper No. 2017.5). University of Oxford. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:620ce18f-69ed-4294-aa85-184af2b5052e

Woolley, S. C., & Howard, P. N. (2018). Computational propaganda: Political parties, politicians, and political manipulation on social media. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190931407.001.0001