The Digipolitical and African Political Thought

A Theoretical Framework to Interpret the Political in the Digital Age

1 Introduction

Digital technologies are becoming increasingly pervasive across all spheres of human social and political life. These technologies blur the distinguishability between our biological, physical, and digital existence in addition to juxtaposing the digital with the analogue. 1 As the analogue sphere contracts, the interplay between the digital and the political becomes more significant. Their relationship has been the object of extensive analyses focused on the effects of (digital) technologies and the digital more broadly on politics. New lexicons – including terms like digital politics, technopolitics, and digital democracy – have become buzzwords in political research. To date, much of the scholarship has focused on the effects of digitality on politics (e.g., Fischli, 2022; Muldoon, 2022; Smith, 2017). These analyses have considered instances of digital politics (broadly understood to be) transposing analogue politics via digital means, exhibiting little receptivity to or integration of arguments that have previously been advanced within debates in science and technology studies. The latter have offered an appreciation of modes of existence that have been triggered by digitality and become pervasive across many aspects of human life, including people’s relations to technology and the non-human (Barad, 2003; Braidotti, 2019; Haraway, 2003; 2008; Lupton, 2016; Verbeek, 2020). Scattering across an interdisciplinary literature to address ontological and relational reformulations, these analyses have only marginally engaged with the political aspect of their critiques.

Against this backdrop, this paper argues for a renewed approach to the digital political sphere – the digipolitical. The premises of this approach rest on an understanding of the digital “revolution” as a phenomenon effecting deep change – one that modifies not only the ways in which individuals operate, communicate, and relate but also the core ontology or onto-relationality of the political subject as well as the ontology of the political itself. In other words, the issue under consideration goes beyond how to conduct politics, extending to what the political is in the digital age.

I argue that three factors have a significant impact on the “new” face of the political in the digital age: the changing nature of political subjects, with digital-humans epitomizing posthuman beings; the characteristics of digitality, a realm of virtuality; and the contextual structure of the digital, which is constructed on, mediated by, and constrained by digits and algorithms. These factors have come to be appreciated in several recently developed disciplines and theories, such as posthumanism and post-phenomenology. However, the focus of inquiry has generally been narrowed to the human; political understandings are yet lacking.

Thus, the theoretical framework that I present in this article covers the insights offered by African political thought to digitality and the digipolitical. I focus on the concept of relationality in African political thought, understood as the condition of existing as relational beings. This mode of existing emphasizes the relevance of relations to that which defines and constitutes the human; it attests to the inextricability of being political to the human’s essence. The notion of relationality developed by African philosophies sheds light on the onto-relational nature of entities interacting in the digipolitical. Moreover, its emphasis on the in-between discloses power structures and dynamics, providing fresh readings on the political as a digital phenomenon.

As many possible techno-centered futures unfold, human and political theorizing is urgent. The epistemic values of the contributions from African political thought decenter and enlarge the repertoire of theoretical frames available to interpret the digipolitical, bolstering studies in comparative political theory (CPT) (Ackerly & Bajpai, 2013). Despite their cultural and geographical origins, the epistemic potential of Africa-generated theories makes them a suitable framework through which to analyze the digipolitical as a global phenomenon.

Conscious of my positionality as a white scholar engaged with African political thought, I adopt a position inspired by “engag[ing] with theories that are strange and estranging rather than familiar and confirmative” (Euben, 2006, p. 196) – meaning a cosmopolitan hermeneutic practice (Godrej, 2009) for knowledge acquisition. This process informs my epistemological position by bringing the scholarly and experiential sphere to the fore. This epistemology does not seek to produce claim validity on a foreign thought system (which African political thought functionally is from my perspective). Rather, it aims to apply acquired notions to construct comprehensive conceptual frames.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. The second section outlines the digital-political conundrum, emphasizing the characteristics of the digital revolution and the digital turn in academia and specifying the theoretical approaches taken in existing political analysis. The third section discusses the theoretical reverberations of the digital, exposing the elements that point to the engendering of new ontological categories. The fourth section advances the nexus between African thought and digitality as theoretical lenses on the digital and the digipolitical. The last section concludes by considering the possibilities for the advanced theoretical framework when it comes to research on African digitality, the digipolitical, and global political thought.

2 The Digital Revolution and Political Analysis

“The digital” has become the defining hot buzzword of the 2020s decade. While surrounding talks, speculations, and critiques have grown in frequency and prominence over time, the discourse has sometimes seemed to border on utopian futurism. Scenarios in which humans and cyborgs coexist alongside digitized, uploaded consciousnesses (see Bostrom, 2009) within digital-only spaces capture just some of the technological developments induced by the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) – a (looming) future toward which humanity is inexorably heading. Notably, however, these tales are not as far from the present as the oft-applied layer of techno-scientific (sur)realism suggests. The digital (digital technologies included) already constitute an inextricable element of our daily lives. Digitality’s intrusion into human life has reshaped the role played by the technologies with which we engage; far from being mere instruments that service humans’ needs, digital devices are reworking the spatio-temporal, ontological, normative, relational, and political dimensions of existence.

Forerunning analyses welcomed “being digital” (1995) with techno-infused optimism, casting digitality as “just” a new form of virtuality (Boellstorff, 2016; Horsfield, 2003; Levy, 1998). As technological developments have unfolded – from upgraded processing speed and internet band coverage to more widespread accessibility of technologies (e.g., computers, smartphones), which made them everyday commodities – the specificities of the digital have begun to appear. To start, the virtuality of the digital is interactive and far more entrenched within the physical and biological sphere than preceding forms of virtual reality (Horsfield, 2003). Digital devices blur the distinguishability between these realms, which become enmeshed as part of a heterogeneous spatio-temporal frame. Moreover, the digital is not appearing slowly or selectively; digital technologies are becoming (if they have not already become) commonplace across all spheres of existence.

Around the world, smartphones have already largely replaced (mobile) phones as our standard means of communication. Text messages and chat apps on smartphones gave way to creative, non-verbal forms of interaction (Sègla, 2019) that ultimately transcended the literate-illiterate divide. The impact of smartphones is not limited to communication, however; they have also deeply altered everyday economic and social dynamics. For instance, fintech solutions like mobile money, which began on the African continent, proved to be so successful that they spread to countries around the world (see Nyabola, 2018). Given its wide-ranging social, political, and economic ramifications, the development of digital technologies functionally represents a revolution that is reshaping every sphere of our existence.

The digital revolution evolved at its own pace, eluding both “old” forms of control and structured theoretical reflection over the course of its development. 2 Today, the everyday use of (or need for) digital devices has transformed the digital into our default mode of operation: “Being online” is now our normalcy (Laterza, 2021b), while “being offline” epitomizes the eventuality of leaving or temporarily pausing the digital 3 (Boellstorff, 2016). As the digital expands, the analogue shrinks; 4 the digital-analogue dualism represents a spiked asymmetry in which the former towers over the latter.

The overtaking of the digital has reshaped not only the engines of society towards datafication but has also had a deep impact on human nature itself. Our systemic, unconditioned, and constant use of digital technologies is “rewiring” our brains, inducing neurological changes and fostering algorithmic thinking (Mbembe, 2016a). Therefore, “to a large extent, [the] software is remaking the human” (Newell & Pype, 2021, p. 18). These changes have triggered the emergence of an “entirely different human being” (Mbembe, 2016a) for whom previously held assumptions, epistemic models, and ontological categories may no longer hold any validity. Furthermore, such datafication, algorithmification, and digitization reverberate beyond the human, impacting the societal and political spheres as well. These alterations do not merely represent the second-order political implications of the rewiring in human brains under the aegis of technology and digitality; rather, they are direct changes to the essence of polities themselves. Nonetheless, there is a limited body of theorizations and reflections on this matter.

To be sure, the digital revolution has ruffled many feathers in political analyses and theorizations. The digital revolution prompted a massive shift in academic research in politics – the digital turn (Aktaş, 2017; Floridi & Noller, 2022; Kneuer & Milner, 2019; Smith, 2017). These reconsiderations emerged from the patent restructuring of the technologies employed for political purposes. Insights from the fields of political communication and media studies are pivotal here. Comparisons between old and new media alongside speculations regarding the limits, possibilities, and potential empowerments brought about by digital platforms and social media (e.g., Bernal et al., 2023; Boczkowski, 2004; Boczkowski & Mitchelstein, 2013; Bruns et al., 2018; Castells, 2010; Dwyer & Molony, 2019; Geschiere, 2021) constitute too large a body of literature to discuss it exhaustively here. Ignited by phenomena like the Arab Spring in the early 2010s and the global populist wave in the late 2010s, such analyses flagged how the political sphere was changing (and continues to change) in a way that saw its operating mechanisms shift from the analogue to the digital. From discussions over the requalification of the public-private divide (Floridi, 2015; Floridi & Noller, 2022) to the emergence of digital public spaces (Kalinka, 2022; Olorunnisola & Douai, 2013), the literature covered the creation of modes of political participation (Nusselder, 2013), technologically aided decision-making mechanisms (Koster, 2022), and paradigms for digital governance and democracy (Fischli, 2022; Muldoon, 2022).

On the one hand, the digital and the techno-shaped infrastructure of politics (or technopolitics) have sparked waves of enchanted optimism. The ease with which digital and online social platforms now involve citizens in political matters has spurred ideas regarding the potential revitalization of political interest and participation, defying the disenfranchisement brought about by “traditional” or “old-fashioned” politics (Smith, 2017). As the digital revolution triggered a necessary reassessment of the political system’s pillars, including notions like the common good, the public sphere, property, privacy, rights, ownership, and the public-private divide (Floridi, 2015), it unveiled the potential for regeneration via the formulation of democratic alternatives crafted specifically for the digital age (Fischli, 2022; Loi et al., 2020; Muldoon, 2022). Such alternatives could be driven by several kinds of democratic inputs, advancing theories on means of doing away with capitalist dominance and reinstating popular sovereignty in the digital (Lando, 2020; McPhail, 2014; Zuboff, 2019).

On the other hand, the technologization of politics raised many eyebrows. In contrast to assertions that it would expand the potential for citizen participation in political affairs, critics argued that technopolitics has enabled stronger and more severe means of control. Surveillance, censorship, segmentation, and repression are all instruments now directly in the hands of governments and tech corporations (Kalinka, 2022; Zuboff, 2019), producing new power hierarchies and asymmetries. Critics have deemed the digital to be responsible for amplifying political phenomena of the analogue, ranging from anti-political sentiments to the ideological void driving a politics without politics alongside post-truth rhetoric, disinformation, and misinformation (see Dean, 2009; Hassan, n.d.). Political trends over the 2010s and 2020s have seen the rise of the far-right and populist movements, both of which speak volumes about the fast-paced disenchantment with longstanding political ideologies and reasoned, programmatic party politics. As technology threatens to swap human reasoning with bureaucratic and algorithmic reasoning, political decision-making is whitewashing individual identities. This context crumbles the foundations for dialogical and reason-based democracy, while appeals to emotion in digitally reconfigured yet lost individuals represent a winning strategy (Mbembe, 2016b).

Regardless of their optimistic or critical standing, existing theorizations generally suffer from similar shortcomings. The first issue is that they simplistically misrepresent the digital as a sphere of communication. This reduction stems from a broad misconceived equivalence between the digital and the Internet, which has long held back the discipline (Berg et al., 2020; 2022). The significant co-production and extensive ties between political and media studies attest to this understanding. Nonetheless, the digital represents far more than a means of communication; it constitutes a sphere ruled under its own normative and ontological order. Anthropological research (Boellstorff, 2008; 2016; Laterza, 2021a; 2021b) largely attests to the significance of the digital as a socio-relational cyberspace. In addition, post-phenomenological approaches corroborate that the mediation of digital technologies is itself invested with power and political intent 5 (Verbeek, 2017; 2020). The second issue is onto-epistemological: Many of the theorizations are narrowly focused on identifying the impacts of technologies on politics or on transposing analogue politics to the digital sphere. These predicaments maintain an overly instrumental understanding of technology: that digital technologies are instruments to be deployed to address humans’ needs. While this has been the case for most technological artifacts and still constitutes part of the rationale underpinning digital technologies, it does not hold true for the digital.

An understanding aimed at the digital’s ontologies, relationalities, and normativities must truly consider how technology operates alongside humans. Next to Don Ihde’s (1979; 2008) pivotal post-phenomenological studies, Donna Haraway’s (1991) reading of the cyborg evokes notions of multiple fluid and co-constituted ontologies that inform relational ontologies (Barad, 2003). These notions expose the ways in which technology acts as a constitutive agent that co-substantiates the analogue. In the analogue-digital dialectic, technology and the digital do not constitute instruments; rather, they are pieces of the onto-relational scheme shaping and defining individuals within their social and political environments.

Thus, the digital – as a technological instance – represents a wide-ranging sphere that is transforming human and political ontologies. The copious references to “re-”attributes (e.g., reworking, reshaping, rewiring) attest to the transformative potential of the digital. While the implications of digital-humans have been considered and mapped across the humanities – including through entirely new disciplines like posthumanism and post-phenomenology – the political remains largely uncharted territory. Political theorists are just beginning to delve deeper into discussion and speculation regarding how the digital is reworking the political. Nonetheless, the political is the inextricable relational component of human existence – a foundational element of any plurality (Agamben, 1996; Arendt, 1958). In addition to ordering and configuring societies, the political defines the ontological, relational, normative, and ethical dimensions of power (Han, 2019). Therefore, an understanding of how the digital is reworking the political is crucial for interpreting the onto-relational scheme governing the digipolitical.

3 The Digipolitical: Digitality and Digital-humanism

Analyses of the digital cannot curtail the political in their understanding. As the digital grows into an all-encompassing sphere that alters and reshapes our everyday realities, power and its intrinsic relationality are subject to alterations at its hands. If we accept that “software is the engine of today’s societies” (Mbembe, 2016a) and that humans are undergoing a “cyborgian neural transformation” (Newell & Pype, 2021, pp. 8 – 9), then an ultimate acknowledgment of the re-programming of the political is inescapable. Just as the digital is impacting individuals’ self-understanding, it is affecting their mutual recognition and relations alongside their conceptions and interactions with reality (Floridi, 2015).

The issue at stake is then how to approach the emerging digipolitical – the post-anthropocentric, digitally infused, techno-mediated rendition of the political. The neologism digipolitical depicts the political (i.e., the sphere ordering power relations in the plurality and constituting the normative blueprint of the polity) reconfigured within the digital; it describes the transformation of the ontological and relational categories underpinning the political engendered by the digital. Within the digital, relational ties of power operate simultaneously across temporalities and spatialities, which bridge or transcend the physical, biological, and digital divide. Power is embodied not only by digitized humans but also by technologies and their functionalities. The digipolitical is enabled and operated through technological artifacts; it is also mediated by both material (e.g., digital devices like smartphones) and immaterial (e.g., the Internet) tools (see Verbeek, 2020). Thus, it operates at high speeds and free of territorial control, escaping the grasp of sovereignty.

Moreover, the digipolitical cuts across societal (a)symmetries to provide direct relational possibilities that transcend space, time, and social statuses. At the same time, the digipolitical creates new divides that are largely shaped by the availability of and knowledge regarding digital technologies. The centrality of the digital creates virtual-analogue asymmetries in which the needs of the physical-biological world and those of the digital reality compete. Existing online has become the means by which one can achieve personal realization to the extent that the need to maintain an online existence – in addition to the need to own means of accessing and engaging with it – is acquiring the same level of perceived importance as having access to basic sanitation, food, and electricity (Lamola, 2021).

For all of these features, the digipolitical constitutes a brand-new study matter – one that requires the formulation of fresh theoretical perspectives. Such perspectives benefit from cross-disciplinary creolization under the big umbrella of “digital studies”; the humanities and social sciences enter into a cooperative dialogue to make sense of notions and creations derived from the biological and technical sciences. This blend of various disciplines and approaches engenders much-needed interdisciplinarity purposefully tailored for inquiring into unprecedented phenomena.

This analytical approach addresses the socio-algorithmic essence of the digital. Far from being a mere mathematically ordered assemblage of data and digits, the digital comprises (virtual) social and political realities. This composition of the digital dissociates its functions from its essence: data and digits have very little in common with human essence or with social or political essence. Notwithstanding the binary code and algorithms underlying it, the digital represents the coming-into-being of new human entities and realities that acquire more and more autonomy each day. This feature makes the digital more than merely another virtuality; it makes it a sui generis virtuality, the purposes of which are derived from the functions it performs and the new ontologies it compiles.

Furthermore, the distinctiveness of the digital rests on its interactive character and the blurred boundaries between the digital, biological, and physical spheres. The digital presence extends beyond its virtuality to engender hybrid spaces in which the digital and the analogue not only interact but also compete. Technological mediation fosters this entanglement and impacts humans’ means of relating. Far from being neutral tools, technological artifacts exert mediation. This mediation is an inherent part of using technologies; they affect both the individual (micro) and socio-political (macro) digital-analogue existence. As the digital is a technology-enabled sphere, considering technological mediation is a sine qua non for understanding the digipolitical.

Technologies represent means of building and defining power relations; they provide the space for political interactions, enable individuals to be involved in political discourse, and determine the topics and the formats of discussions (Kalinka, 2022; Verbeek, 2017). The existence of such political spaces is, thus, dependent on the maintenance of these digital technologies: The algorithmically structured digipolitical relies on technological infrastructure to exist and operate. These technologies embody the virtuality themselves; the digipolitical would dissolve without them.

Technology determines the structure and the content of digital relations. The algorithmic architecture of the digital designs social circles and structures using quantitative approaches, including data classification, segmentation, and profiling (Kalinka, 2022; Rouvroy, 2020; Zuboff, 2019). These methods serve to determine digital relationalities, clashing spatial borders while facilitating digital compartmentalization and creating echo chambers. This data-driven clustering resonates with the kinds of content generally transmitted in digital interactions. The spread of the digital has been accompanied by the expansion of internet coverage, an increase in internet speeds, and a dramatic rise in the accessibility of ICTs (information and communication technologies). Notably, ICTs are deemed responsible for the constant and overabundant flow of information available anytime and anywhere (Floridi, 2015; Geschiere, 2021; Mbembe, 2016a, 2016b). Not only does such information overload challenge our cognitive capabilities, but it also bends them towards visuality. The digital tends to use multimedia (e.g., images, audio, videos) rather than plain text. Daily exposure to information disseminated in this manner promotes visual or eidetic reasoning and relating – a form of thinking strongly anchored in audio-visual dimensions that shape people’s modes of reasoning and patterns of cognitively absorbing and processing information. However, this eidetic shift is not limited to the digital. Considering that “we live in a world where it is quite common for the physical to simulate the digital” (Boellstorff, 2016, p. 397) on the merits of norms, assumptions, and networks, steering our social interactions, this digitally promoted turn to visual-eidetic thinking epitomizes another way in which digitality impacts the physical-biological – impacts our very human wiring (Mbembe, 2016a).

Of course, this shift to eidetic is rooted in the deciphering instrument that enables it: the screen. The screen embodies the digital’s existence and our existence within digitality. It serves as a tool that conveys our digital existence while substantiating the possibility of the digital. Effectively, the screen embodies a spatio-temporal unbounded yet hyperconnected virtuality in which individuals’ alter-egos exist and relate to one another. To describe human entities existing and relating within the digital, the literature has coined terms like “digital-double,” 6 “digital self,” and homo cyber (Boellstorff, 2008; Laterza, 2021b; Nusselder, 2013). These terms refer to machine- or technology-enabled representations of the analogue human, self, or ego that exist within a world of virtuality – a multi-interactive digital virtual reality.

I refer to these posthuman and post-anthropocentric cases as “digital-humans.” Their onto-relational novelty substantiates their posthuman character, as they break free from Cartesian and Enlightenment humanism. Digital-humans are non-human humans: Their inclusion in humanity attests to a notion of humanity that is inclusive of entities beyond the scope of anthropocentrism (Ferrando, 2016; Gladden, 2019). Thus, a post-anthropocentric understanding undergirds this inclusion. Philosophical considerations of digital-humans (technology-sustained derivatives of humans) as non-humans equally displace the centrality and primacy of the human as narrowly considered to refer to Homo sapiens. From a post-anthropocentric perspective, humans and non-humans – but also technology and nature – are mutually constitutive and relate to one another on equal terms (Barad, 2003; Ferrando, 2019; Haraway, 2003).

Digital-humans stem from and maintain a dialectical relationship with their analogue counterpart. This does not consequentially imply any conditions of physical enhancement or biological changes to be implemented on the physical-analogue individual. Moreover, the notion of digital-humans does not insinuate alterations to or the annihilation of the analogue self. In other words, digital-humans are onto-relational new beings that feed from their analogue blueprint to produce a digital replica. The stable maintenance of dialectical relations between the analogue and the digital consecrate their autonomy and interrelationality; while they differ in onto-relational terms, the analogue subject and the digital subject are inextricably linked and constantly informing one another. Nonetheless, this does not cause an ontological reformulation of the analogue self: An onto-relational alteration of the analogue self cannot strictly be read as a straightforward consequence of the existence and traits of the digital self.

A clear threshold separates digital-humans from their analogue counterpart: the definition of the ontological and relational logic of digital entities in accordance with digital virtuality’s characteristics. As they relate within virtuality, digital-humans can enjoy unbound spatial and temporal possibilities alongside connectivities that transcend the impediments of the physical and the analogue. The implications of their lack of embeddedness are contradictory. On the one hand, the lack of contingency in digital relating can constitute a factor that strengthens commonalities and relational ties in the digital (Morgan & Okyere-Manu, 2021), which then crisscross regional, transnational, and international connectivities. On the other hand, unconstrained digital relationality can easily transform into ethical aporia or alienation. Relating within a virtual, unbounded sphere can lead to detachment from the self as well as the absence of a group for identity formation (Nusselder, 2013); moreover, it can cause an ethical and normative vacuum, hindering relationships and co-existing.

All the points considered above frame digital-humans as onto-relationally different beings for whom there is still no established frame of understanding. Few studies have considered the inflection of digital ontological relations in political analyses. According to T. Boellstorff (2008, p. 29), the “homo cyber” comprises “forms of sociality and selfhood in the digital world” that retain profound human essence. Far from being the end of humans, digital-humans are reconfigured differently; in being virtual, they are humans. It is the reworking of virtuality that characterizes them as human in the actual world, operating via the co-constitutive ontology enlacing the digital with the analogue (Boellstorff, 2008). Therefore, the rethinking of the human as a digital-analogue co-production introduces a regenerated idea of the human inscribed in a post-anthropocentric vision.

Moving beyond dialectically reconfiguring analogue-physical humans in juxtaposition to the digital (e.g., Boellstorff, 2016; Laterza, 2021b; Nusselder, 2013), philosophical endeavors have speculated on the ontological, normative, ethical, and relational modalities for this kind of screen-mediated human in the present and future of humanity. Philosophical and cultural posthumanism 7 (e.g., Braidotti, 2019; Ferrando, 2019; Gladden, 2018; Hayles, 2003; 2004; Lamola, 2020) reframe humans and their relational existence in post-anthropocentric and post-dualistic terms (e.g., Barad, 2003; Braidotti, 2019; Ferrando, 2019). A posthuman understanding does not suggest the end of the human; rather, it signifies a renewed understanding of the human beyond anthropocentric tenets – a de-centering of the human and the anthropomorphizing of the digital.

This reappreciation of the human implies a reassessment of the human-centered hierarchic schemata. An emphasis on relationality displaces the human as the central unit for ontologies and relations. In this light, the human is one parcel of a horizontal axis that includes the non-human, nature, and technology. These elements are not only interrelated but co-occurring in the creation of queered ontologies (Barad, 2003), the hallmark of which is essentially post-anthropocentric. Thus, while post-anthropocentrism is not a necessary condition for relationality, the latter is a sine qua non for conceiving of a multi-composite universe that equally yet asymmetrically entangles the human, the non-human, nature, and technology. This approach discloses new and previously marginal understandings by providing decolonial lenses through which to read the political environment. The displacement of the human as the central unit of analysis offers space in which to re-approach political concepts and formulate fresh readings (Dokumaci, n.d.). In addition, it invites a variety of thought traditions to contribute to and decenter the debate. Furthermore, the relational approach clarifies the influence of technological mediation and algorithmic influence on the development of relations within the digipolitical, revealing its political significance. As relationality defines the blueprints underlying power relations, the characteristics of the digital-analogue dialectic (along with its hybrid spaces) warrant the political consideration of their onto-relationalities.

4 Insight from African Political Thought

To date, the debate on relationality in posthuman theories remains confined to a Western-centric debate. This exclusivity reinforces epistemic asymmetries and knowledge-making inequalities that have left many traditions of thought unprepared to deal with the digital revolution occurring in both the academic and empirical worlds (Lamola, 2021). While this monologue (so to say) invites us to consider which aspects of the digital are granted attention in different geographical and socio-cultural settings, it also raises questions over which and whose voices are steering the sense-making and the interpretations of the reality in which we are living. In an effort to open the debate, this article argues for the introduction of philosophies keen on including the concept of relationality – African political thought included – in debates on post-humanism and post-anthropocentrism.

The inclusion of thought traditions often considered “marginal” aligns with the aims of CPT. The latter is a relatively recent sub-discipline of political theory that seeks to decolonize, enlarge, decenter, and democratize the study of political thought and phenomena (Ackerly & Bajpai, 2013; Euben, 1997; Freeden & Vincent, 2013; Von Vacano, 2015). CPT exhorts scholars to draw parallels between ideas conceptualized in spatially and chronologically diverse settings (March, 2009) as well as to reconsider the theoretical, epistemic, and normative dimensions of concepts central to political theory and practice beyond a strict comparative perspective (Dokumaci, n.d.; El Amine, 2016). Thus, the concept of relationality epitomizes the elements that link posthuman theories to African political thought despite their apparent lack of historical exchanges.

African political thought has long insisted on a relational approach to human and political ontologies; in this way, it aligns with many philosophies from both the East and the West, which have long considered being relational as foundational to humans’ political nature. The works of such African philosophers as Masolo (2010), Matolino (2018), Menkiti (2004), and Wiredu (2007) emphasize interconnectedness as the condicio per quam of polities and of human essence. 8 The centrality of relationality accompanies the abdication of a dualistic understanding of reality. Abandoning Cartesian dichotomies that juxtapose the human with nature, the natural with the social, and the subject with the object, the relational focus in African philosophies emphasizes notions of co-becoming, being-together, and co-existentiality (Menkiti, 2004; Metz, 2012a). 9 Under these terms, understanding the human is not only an ontological venture but also an onto-relational one with political (as well as normative, ethical, and metaphysical) implications. Thus, being political appears to represent an inherent facet of being human, as relating is intrinsic to existing.

The condition of existing as a relational being marks a mode of living in the continuum that contraposes individualism with communalism. The high praise given to relational ties in African political thought is consistent with the formulation of political philosophies like Ubuntu and African communitarianism – cognates of many communo-centered philosophies in both the West (e.g., communitarianism, network theories) and the East (e.g., Buddhism, Confucianism). Gyekye and Wiredu (1992) describe African political philosophies as organicist, meaning that their currents of thought stress the relations and ties bonding individuals together (Bongmba, 2001; Masolo, 2010; Wiredu, 1996). These bonds exemplify the central matter of concern for ethical, normative, political, and ontological matters: the network of relations, and the maintenance of these ties.

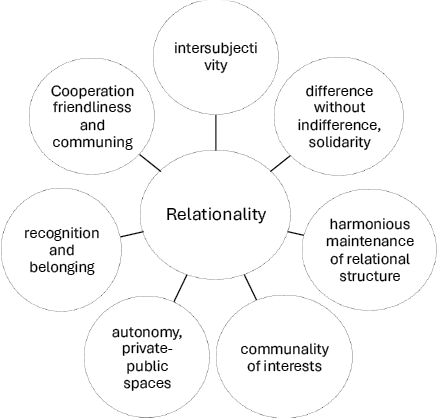

Figure 1 below offers a visual representation of the centrality of relationality. The latter operates as the core that sustains and provides the rationale for the tenets structuring African communitarianism and Ubuntu. The emphasis on relational ties provides the basis from which concepts ordering the social, political, and moral spheres are derived.

Figure 1: Tenets of African political thought. Source: drafted by the author

Ubuntu and African communitarianism’s empirical manifestation constructs societal formations aimed at the harmonious maintenance of the relational structure, emphasizing elements of cooperation, friendliness, and communing (Metz, 2012b). They work through a system of recognition and belonging, underpinning forms of intersubjectivity that transcend the private-public divide. For instance, Elias Bongmba (2001) reflects on how marriage is not just a personal or familiar matter but one that involves the entire community in approving a union. This pervasiveness of relations should not be conflated with the towering of a homogenous community over the individual, for solidarity and reciprocity sacralize the right to differ while decrying indifference (Masolo, 1994).

The insistence on relationality as a centerpiece of African political thought in this article finds its rationale in the unifying role that this concept plays among the aforementioned elements. The primacy of the relational sphere justifies the normative and metaphysical dimensions of human and political life, as all can be tied back to it. It signifies the condition of being as a relational being, or rather that of existing as a political entity. Putting aside Cartesian and atomistic views, African political thought reads relationality as humans’ connection to one another in the social and political spheres. This mode of existence underpins the socio-political communitarian system, the telos of which is to foster ties among individuals in order to harmoniously maintain the structure and, in turn, enable relations. Relationality frames humans’ connections in the social and political spheres, in which power manifests as coercive, authoritarian, hierarchical, reciprocal, or cooperative.

Transposing this relational reading to beyond-human, non-human, and posthuman instances sheds light on the analytical potentials of relationality. African and Africanist philosophers have long debated humanism and the human-centered project of African thought (e.g., Bell, 2002; Gyekye, 2011; Hoffmann & Metz, 2017; Horsthemke, 2018; Marzagora, 2016; Metz, n.d.; Rettová, 2023). While the disputes persist, the anthropocentrism in African thought now faces an empirical challenge presented by digitality: the hybridization of selves and the (physical) interference of digital-humans. The notion of relationality dear to this tradition of thought is undergoing a transformative phase that stretches its applicability from the human to the non-human as well as to the post-, digital-human. This shift somehow forced the transfiguration of human relationality to embrace tech-mediated entities, though it has rarely been covered in the literature with only a few exceptions (e.g., Jurova, 2017; Morgan & Okyere-Manu, 2021; Nyabola, 2018). Still, it has been confirmed by factual occurrences. The latter speak of digital-analogue imbrications in which invested political agents have human and non-human (digital) natures, creating complex and multiple onto-relationalities.

The idea of relationality expressed in African political thought represents a valuable tool with which to interpret digital (as well as hybrid) multiple and co-constituted realities. The latter constitute part of contemporary virtual and analogue realities, which result from the co-implication of the non-linear intertwining of the human, the non-human, the digital, technology, and nature in processual and interdependent being (see Mbembe, 2016a). These realities give away the certainty of positivist and Cartesian categories to offer indeterminate foundational natures. The human entangles with the non-human as reciprocally definable elements. Their essential categories are not fixed, but changeable: a process resulting from their interacting and relating in ontological terms (Barad, 2003). Likewise, digital, hybrid, and analogue realities reciprocally inform one another, giving way to multiple levels of interdependency.

Digital-humans represent one instance of these interactions: While confined to a device’s screen, their online digital interactions impact analogue lives. Despite their distinguishability, there are no clear boundaries that separate the existence of the analogue from that of the digital-human; analogue and digital existence can (and do) differ, yet they reciprocally influence one another. These implications not only reconfigure both subjects but also attest to their co-existentiality.

In interpreting the digipolitical, the concept of relationality has a Janus face. First, relationality represents an element that is itself transformed by the digital. Extending beyond the physical, relations embrace humans, non-humans, and nature – but also technology and digital-humans. The tenets underpinning these relationalities have yet to be properly explored. Second, the role of relationality is essentially reverted in this interpretation to being an analytical instrument. The concept serves as a lens of analysis, revealing how connections build the virtual reality of the digital – its political character and the political agency of the entities (human and technological) operating in the digital.

Considering the twofold theoretical relevance of relationality, I suggest a consequential reading of digital relationality that considers a) digital relationality; b) digital-humans’ onto-relationality; and c) the digipolitical. This reading departs from the analysis of the tenets of digital relationality – from the mode of existing, relating, and connecting as actions shaped by the characteristics of digital virtuality as a cyber-relational space. This understanding provides the building blocks with which to decipher digital-humans’ onto-relationality. In addition to ontological analyses that disclose the posthuman essence of these contemporary political subjects, their relational nature demands consideration. Is the relationality intrinsic to (analogue) human nature an innate characteristic of digital-humans as well? If so, would it make sense to speak of posthuman or post-anthropocentric relationality? The digital is undoubtedly a space charged with political power; nonetheless, the political nature of this space, its agents, and performativity remain unclear. In reading the digipolitical, it is imperative to grant equal attention to the digital-humans, to normativities, and to the relational environment that materializes exchanges and power structures via technological mediation.

A posthuman and post-anthropocentric approach to relationality 10 embraces the many agents and political subjects involved in the political today. In other words, such an approach recognizes the diverse subjects that take part in the relational scheme building the structures of power. Through a narrowing to the digital, a posthuman and post-anthropocentric relationality relieves the central emphasis placed on the (analogue) human, considering human interplay with tech-enabled human forms. This understanding reveals a fundamental reworking of relations between humans and digital-humans as well as those between humans and machines.

What is more, the post-anthropocentric relational approach inscribed in African political thought reveals a co-constituency of subjects and relations, exposing the architecture of power that they form. The focus on the in-between – the visible and hidden spaces as well as the connectors from which relations grow – as loci of power enables analytical understandings of lines and formations of power among individuals, institutions, and technology. This crisscrossing of boundaries holds the epistemic potential to reveal (re)workings of power relations from humans to digital-humans or from digital-humans to human-machines.

Moving from the algorithm to the analogue and vice versa, the relational approach in African thought evidences the non-linearity of analogue-digital transitions and their hybrid formations. In other words, an African epistemic reading of the digipolitical does not equate to the attribution of a communitarian character to structures of political power in the digital or indulge the naïveté of straightforward analogies between the analogue reality and the digital reality. Interpreting digital relationality exposes multiple forms of political relations, including those that go far and beyond those ascribed to the traditions of Ubuntu and African communitarianism. This reading aims to give way to new and still-forming paradigms while contributing to the development of internationally comprehensive theoretical frameworks, informed by materialities and historical contingencies, for reading the digipolitical. These aspirations informed this analysis of the digipolitical and heightened its worldliness.

5 Conclusions

The fast-paced exponential adoption of digital technologies has triggered a silent techno-computational revolution (Mbembe, 2016a) that is impacting individuals’ daily lives in Africa and around the world. The resultant changes are affecting every dimension of human life, from communication to reasoning. However, this revolution is also offering new possibilities to articulate existence in the digital. Transcending the analogue, physical, and biological dimensions, the digital revolution is enabling cyber social-political practices in which analogue and digital posthuman subjects interact. The political humanness with which digital-humans are endowed, the chrono-spatial collapse, and the algorithmic traits of the digital are reconfiguring the ontological, relational, and normative dimensions of the political, riveting the digipolitical.

This article advocates for an African-inspired theoretical approach to the digipolitical – one that nourishes a relational reading anchored in posthuman and post-anthropocentric understanding. This analysis of the digital centered on relationality functions as a political lens that effectively suits the processual, intertwined, co-constitutive categories building post-anthropocentric ontologies as well as the telos of the digipolitical. To date, African philosophies have engaged little with posthuman debates and scholars, often circumscribing (post-)anthropocentric issues to animal non-humans (see Horsthemke, 2018; Metz, n.d.). Against this backdrop, this article invites us to appraise the notion of relationality inscribed in African political thought due to the epistemic validity of its interpretation of multiple, fluid, and hybrid ontologies. This suitability stems from African philosophies’ reading of political humanness as a characteristic inherent within individuals – one that developed in co-existentiality with others. This understanding locates power in the relations that bond subjects. Such a relational approach sheds light on posthuman reconfigurations of power within which political relations entangle the human and the non-human.

This relational reading is part of a decentering approach to the political that abandons anthropocentric, Cartesian grounds in order to consider non-dualistic ontologies and relationalities. It can give way to a dialogue among various traditions of political thought and multi-composite epistemologies. By emphasizing the centrality of relationality, African thought presents a propitious theoretical framework through which to inquire into the digital, digital-humans, and the digipolitical. However, this emphasis does not equate to advocating for an Afro-centric or communitarian-inspired analysis of the digital. The resort to African political thought lies in its capacity to elucidate the use of relationality as a cornerstone for the political. This reading discloses the multifaceted, pluralistic, and diverse characteristics of power in the digital. Against the backdrop of a scholarship that has given preference to liberal and capitalist models to shift analytical critiques to the digital, this relational approach has the potential to inform readings aimed at moving beyond consumeristic, utilitarian, and exploitative models that foreground individualistic tenets.

The relational perspective strengthens the worldliness of the digipolitical by revealing nuances in the dynamics, structures, uses, and abuses of power in the digital. This theoretical lens serves as an interpretive instrument that aids in the generation of a better understanding of the variety of techno-related phenomena and power dynamics. Despite not being directly aimed at making recommendations or predictions, this relational reading of the digipolitical offers us an understanding of a globally pervasive phenomenon that departs from a spatially bound set of theories. This not only impacts considerations of geographical and cultural significance in the borderless digital age (Floridi, 2015) but also provides a sound basis for the emerging regulatory frameworks, legal provisions, rights protections, and policy formulations geared to normatively define the digipolitical.

References

Ackerly, B., & Bajpai, R. (2013). Comparative political thought. In A. Blau (Ed.), Methods in analytical political theory (pp. 270–296). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203094341

Agamben, G. (1996). Mezzi senza fine. Note sulla politica. Bollati Boringhieri Editore.

Aktaş, H. (2017). Digital politics. In B. Ayhan (Ed.), Digitalization and society(pp. 75–90). Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003087885-12

Arendt, H. (1958). The human condition. University of Chicago Press.

Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28(3), 801–831. https://doi.org/10.1086/345321

Bell, R. H. (2002). Understanding African philosophy. A cross-cultural approach to classic and contemporary issues. Routledge.

Berg, S., Rakowski, N., & Thiel, T. (2020). The digital constellation. (Weizenbaum Series, 14). https://doi.org/10.34669/wi.ws/14

Berg, S., Staemmler, D., & Thiel, T. (2022). Political theory of the digital constellation. Zeitschrift Für Politikwissenschaft, 32(2), 251–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41358-022-00324-4

Bernal, V., Pype, K., & Rodima-Taylor, D. (Eds.). (2023). Cryptopolitics: Exposure, concealment, and digital media. Berghahn Books.

Boczkowski, P. (2004). Digitizing the news: Innovation in online newspapers. MIT Press.

Boczkowski, P., & Mitchelstein, E. (2013). The news gap: When the information preferences of the media and the public diverge. MIT Press.

Boellstorff, T. (2008). Coming of age in second life: An anthropologist explores the virtually human. Princeton University Press. https://repositorio.ufsc.br/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/167638/341506.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y%0Ahttps://repositorio.ufsm.br/bitstream/handle/1/8314/LOEBLEIN%2C LUCINEIA CARLA.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y%0Ahttps://antigo.mdr.gov.br/saneamento/proees

Boellstorff, T. (2016). For whom the ontology turns: Theorizing the digital real. Current Anthropology, 57(4), 387–407.

Bongmba, E. K. (2001). African witchcraft and otherness: A philosophicak and theological critique of intersubjective relations. State University of New York Press.

Bostrom, N. (2009). The future of humanity. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations. https://doi.org/10.1515/humaff-2021-0002

Braidotti, R. (2019). Posthuman knowledge. Polity.

Bruns, A., Enli, G., Skogerbo, E., Larsson, A. O., & Christensen, C. (Eds.). (2018). The Routledge companion to social media and politics.

Castells, M. (2010). The Rise of the Network Society (2nd ed.; Vol. 1 of The information age: Economy, society and culture). Wiley Blackwell.

Dean, J. (2009). Politics without politics. Parallax, 15(3), 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13534640902982579

Dokumaci, P. (n.d.). Relationality, comparison, and decolonising political theory.

Dwyer, M., & Molony, T. (Eds.). (2019). Social media and politics in Africa: Democracy, censorship and security. ZED.

El Amine, L. (2016). Beyond East and West: Reorienting political theory through the prism of modernity. Perspectives on Politics, 14(1), 102–120. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592715003254

Euben, R. L. (1997). Comparative political theory: An Islamic fundamentalist critique of rationalism. The Journal of Politics, 59(1), 28–55. https://doi.org/10.2307/2998214

Euben, R. L. (2006). Journeys to the other shore: Muslim and Western travelers in search of knowledge. Princeton University Press.

Ferrando, F. (2016). The party of the Anthropocene: Post-humanism, environmentalism and the post-anthropocentric paradigm shift. Relations, 4(2), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.7358/rela-2016-002-ferr

Ferrando, F. (2019). Philosophical posthumanism. Bloomsbury Academic.

Ferrando, F. (2021). Beyond posthuman theory: Tackling realities of everyday life. Journal of Posthumanism, 1(2), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.33182/jp.v1i2.1840

Fischli, R. (2022). Data-owning democracy: Citizen empowerment through data ownership. European Journal of Political Theory, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/14748851221110316

Floridi, L. (2015). The onlife manifesto. In L. Floridi (Ed.), The onlife manifesto: Being human in a hyperconnected era. Springer Open. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04093-6

Floridi, L., & Noller, J. (2022). The green and the blue: Digital politics in philosophical discussion. In L. Floridi & J. Noller (Eds.), The Green and the Blue. Verlag Karl Alber. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783495998335

Freeden, M., & Vincent, A. (Eds.). (2013). Comparative political thought: Theorizing practices. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203094341

Geschiere, P. (2021). Dazzled by new media: Mbembe, Tonda, and the mystic virtual. African Studies Review, 64(1), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2020.80

Gladden, M. E. (2018). A typology of posthumanism: A framework for differentiating analytic, synthetic, theoretical, and practical posthumanisms. In M. E. Gladden (Ed.), Sapient circuits and digitalized flesh: The organization as locus of technological posthumanization. Defragmenter Media. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739908-2

Gladden, M. E. (2019). Who will be the members of Society 5.0? Towards an anthropology of technologically posthumanized future societies. Social Sciences, 8(5), 0–39. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8050148

Godrej, F. (2009). Towards a cosmopolitan political thought: The hermeneutics of interpreting the other. Polity, 41(2), 135–165. https://doi.org/10.1057/pol.2008.28

Gyekye, K. (2003). Person and community in African thought. In P. H. Coetzee & A. P. J. Roux (Eds.), The African philosophy reader: A text with readings. Routledge.

Gyekye, K. (2011). African ethics. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia Of philosophy. Plato.Stanford.Edu/Archives/Fall2011/Entries/African-Ethics/

Gyekye, K., & Wiredu, K. (Eds.). (1992). Person and community: Ghanaian philosophical studies I. Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. https://philpapers.org/rec/GYEPAC

Han, B.-C. (2019). What is power? Polity Press.

Haraway, D. (1991). A cyborg manifesto: Science, technology, and socialist-feminism in the late twentieth century. In Simians, cyborgs and women: The reinvention of nature (pp. 149–181). Routledge.

Haraway, D. (2003). The companion species manifesto: Dogs, people, and significant otherness. Prickly Paradigm.

Haraway, D. (2008). When species meet. University of Minnesota Press.

Hassan, R. (2018). There isn’t an app for that: Analogue and digital politics in the age of platform capitalism. “What then shall we choose? Weight or lightness?” Media Theory, 2(2), 1–28. http://mediatheoryjournal.org/

Hayles, K. N. (2003). Afterword: The human in the posthuman. Cultural Critique, 53, 134–137. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1354628

Hayles, K. N. (2004). Refiguring the posthuman. Comparative Literature Studies, 41(3), 311–316. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40247415

Hoffmann, N., & Metz, T. (2017). What can the capabilities approach learn from an Ubuntu ethic? A relational approach to development theory. World Development, 97, 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.04.010

Horsfield, P. G. (2003). The ethics of virtual reality: The digital and its predecessors. Media Development, 50(2), 48–59.

Horsthemke, K. (2018). African communalism, persons, and the case of non-human animals. Filosofia Theoretica: Journal of African Philosophy, Culture and Religions, 7(2), 107–109. https://doi.org/10.4314/ft.v7i2.5

Ihde, D. (1979). Technology and human self-conception. The Southwestern Journal of Philosophy, 10(1), 23–34. https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ihde, D. (2008). Introduction: Postphenomenological research. Human Studies, 31(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/sl0746-007-9077-2

Jurova, J. (2017). Do the virtual communities match the real ones? (communitarian perspective). Communications - Scientific Letters of the University of Žilina, 19(1), 14–18. https://doi.org/10.26552/com.c.2017.1.14-18

Kalinka, I. (2022). The politics of appearance on digital platforms: Personalization and censorship. Zeitschrift Für Politikwissenschaft, 32(2), 531–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41358-021-00307-x

Kneuer, M., & Milner, H. V. (2019). The digital revolution and its impact for political science. In M. Kneuer & H. V. Milner (Eds.), Political science and digitalization: Global perspectives (pp. 7–21). Verlag Barbara Budrich. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvm7bc05.3

Koster, A.-K. (2022). Das ende des politischen? Demokratische politik und künstliche intelligenz. Zeitschrift Für Politikwissenschaft, 32(2), 573–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41358-021-00280-5

Lamola, M. J. (2020). Covid-19, philosophy and the leap towards the posthuman. Phronimon, 21(February), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.25159/2413-3086/8581

Lamola, M. J. (2021). Introduction: The crisis of African studies and philosophy in the epoch of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Filosofia Theoretica: Journal of African Philosophy, Culture and Religions, 10(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4314/ft.v10i3.1

Lando, A. L. (2020). Africans and digital communication at crossroads: Rethinking existing decolonial paradigmns. In K. Langmia & A. L. Lando (Eds.), Digital communications at crossroads in Africa: A Decolonial Approach (pp. 107–130). Palgrave Macmillan.

Laterza, V. (2021a). (Re)creating “society In Silico”: Surveillance capitalism, simulations and subjectivity in the Cambridge Analytica data scandal. Partecipazione e Conflitto, 14(2), 954–974. https://doi.org/10.1285/i20356609v14i2p954

Laterza, V. (2021b). Human-technology relations in an age of surveillance capitalism. EthnoAntropologia, 9(2). http://rivisteclueb.it/riviste/index.php/etnoantropologia/issue/view/30/showToc

Levy, P. (1998). Becoming virtual: Reality in the digital age (R. Bononno, Trans.). Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.36-1612

Loi, M., Dehaye, P. O., & Hafen, E. (2020). Towards Rawlsian “property-owning democracy” through personal data platform cooperatives. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 26(6), 769–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230.2020.1782046

Lupton, D. (2016). Digital companion species and eating data: Implications for theorising digital data–human assemblages. Big Data and Society, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951715619947

March, A. F. (2009). What is comparative political theory? The Review of Politics, 71, 531–565.

Marzagora, S. (2016). The humanism of reconstruction: African intellectuals, decolonial critical theory and the opposition to the posts (postmodernism, poststructuralism, postcolonialism). Journal of African Cultural Studies, 28(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2016.1152462

Masolo, D. A. (1994). African philosophy in search of identity. Indiana University Press, Edinburgh University Press in association with the International African Institute.

Masolo, D. A. (2010). Self and community in a changing world. Indiana University Press.

Matolino, B. (2014). Personhood in African philosophy. Cluster Publications.

Matolino, B. (2018). The politics of limited communitarianism. Filosofia Theoretica: Journal of African Philosophy, Culture and Religions, 7(2), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.4314/ft.v7i2.7

Mbembe, J.-A. (2016a, December 1–3). Future knowledges [Conference presentation]. African Studies Association Annual Meetings, Washington, D.C. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J6p8pUU_VH0

Mbembe, J.-A. (2016b, December 22). The age of humanism is ending. The Mail & Guardian. https://mg.co.za/article/2016-12-22-00-the-age-of-humanism-is-ending/

McPhail, T. L. (2014). eColonialism theory: How trends are changing the world. The World Financial Review.

Menkiti, I. A. (1984). Person and community in African traditional thought. In R. Wright (Ed.), African philosophy: An introduction. University Press of America.

Menkiti, I. A. (2004). On the normative concept of a person. In K. Wiredu, W. E. Abraham, A. Irele, & I. A. Menkiti (Eds.), A companion to African philosophy (pp. 324–331). Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Metz, T. (n.d.). A relational theory of animal moral status.

Metz, T. (2012a). African conceptions of human dignity: Vitality and community as the ground of human rights. Human Rights Review, 13(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12142-011-0200-4

Metz, T. (2012b). Developing African political philosophy: Moral-theoretic strategies. Philosophia Africana, 14(1), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.5840/philafricana20121419

Morgan, S. N., & Okyere-Manu, B. D. (2021). African ethics and online communities: An argument for a virtual communitarianism. Filosofia Theoretica: Journal of African Philosophy, Culture and Religions, 10(3), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.4314/ft.v10i3.7

Muldoon, J. (2022). Platform socialism: How to reclaim our digital future from big tech. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qDRf4KTSO_o

Negroponte, Nicolas (1995). Being Digital. Alfred A. Knopf.

Newell, S., & Pype, K. (2021). Decolonizing the virtual: Future knowledges and the extrahuman in Africa. In African Studies Review, 64(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2020.88

Nusselder, A. (2013). Twitter and the personalization of politics. Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, 18(1), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1057/pcs.2012.45

Nyabola, N. (2018). Digital democracy, analogue politics: How the internet era is transforming Kenya. Zed Books.

Olorunnisola, A. A., & Douai, A. (Eds.). (2013). New media influence on social and political change in Africa. IGI Global.

Ramose, M. B. (1999). African philosophy through Ubuntu. Mond Books.

Rettová, A. (2023). The nonhuman in African philosophy. In B. Freter, E. Imafidon, & M. Tshivhase (Eds.), Handbook of African philosophy (pp. 431–456). Springer Verlag.

Rouvroy, A. (2020). Algorithmic governamentality and death of politics. Green European Journal.

Sègla, A. D. (2019). Mobile apps for the illiterate. TATuP - Zeitschrift Für Technikfolgenabschätzung in Theorie Und Praxis, 28(2), 50–51.https://doi.org/10.14512/tatup.28.2.s50

Smith, T. G. (2017). Politicizing digital space: Theory, the Internet, and renewing democracy. University of Westminster Press.

Verbeek, P. P. (2017). The struggle for technology: Towards a realistic political theory of technology. Foundations of Science, 22(2), 301–304.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-015-9470-7

Verbeek, P. P. (2020). Politicizing postphenomenology. In G. Miller & A. Shew (Eds.), Reimagining philosophy and technology, reinventing Ihde (pp. 141–155). Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35967-6_9

Von Vacano, D. (2015). The scope of comparative political theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 18(February), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-071113-044647

Wiredu, K. (1996). Cultural universals and particulars: An African perspective. Indiana University Press.

Wiredu, K. (2007). Democracy by consensus: Some conceptual considerations. Socialism and Democracy, 21(3), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/08854300701599882

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for the future at the new frontier of power. Profile Books.

Conflict of Interest Statement

No conflicts of interest arise from this study.

Acknowledgements

It has been a long way between the earliest drafts of this paper and the final version published here. Revisions and reflections benefitted immensely from the feedback provided to me by Alena Rettová and through my discussions with Benedetta Lanfranchi, Albert Kasanda, and Farhad Mani. I am truly grateful to the blind reviewers for their comments. I am especially appreciative of Reviewer A for their detailed remarks and literature suggestions, which highly improved the quality of my argument.

Date received: February 2024

Date accepted: November 2024

1 In the text, the digital is defined as all that is code-based and made intelligible via the screen of a digital device, while the analogue refers to existence unmediated by technology and pursued through non-digital means.

2 Today, the literature and research on the digital is evidently diffuse, causing positive interdisciplinary hybridizations but also hindering the creation of an integrated and comprehensive theoretical frame.

3 The reference to online and offline inherent in the idea that the “offline is increasingly experienced as the temporarily not online” (Boellstorff, 2016) risks fostering an equivalence between the digital and the Internet. This is a misrepresentation of the digital, which, in actuality, includes the Internet alongside all the virtualities that are created, mediated, and reproduced through a device’s screen, regardless of whether that device is connected to the Internet. Of course, the complementarity binding the digital and the Internet is undeniable; while distinct, they need each other to operate as a cohesive socio-cyber space.

4 The analogue represents all that is not affected by the digital. Notably, the analogue is not coincident with the physical and the biological, as the digital exists alongside, impacts, and shapes these two spheres. Therefore, what is left for the analogue is a dimension that is weakening further each day.

5 Verbeek’s analysis seeks to reconcile the phenomenological and the political by focusing on the political significance held by technological artifacts. His considerations offer an understanding in which technology is an object and agential subject, in political terms, rather than a contingency of political relations, interactions, and issues (Verbeek, 2017; 2020).

6 The idea of a digital-double originated in the field of computer science to refer to the reproduction in silico of worldlyelements with the purpose of digitally modeling them. Scholars in the humanities appropriated the term to refer to one’s online existence in juxtaposition to their analogue life (Laterza, 2021a).

7 Posthumanism includes a broad variety of understandings ranging from techno-savvy approaches, projects, and beliefs regarding the future of humanity to epistemological critiques linked to materialism, humanism, existential philosophy,feminist thought, and eco-critique (Braidotti, 2019; Ferrando, 2019; Gladden, 2018; Lamola, 2020).

8 This characterization of the human is supported in various African philosophies, including Ubuntu, the renowned maxim of which asserts the following: “I am because you are.” This is a succinct statement encapsulating the understanding that the creation and maintenance of ties with other individuals grants one personhood rather than the status of a “mere” human being. For an overview of the larger debate on personhood in African philosophy grounded on reciprocating and relationality, see Gyekye (2003), Matolino (2014), Menkiti (2004), Metz (2012b), and Ramose (1999).

9 Currents of African political thought accord varying degrees of emphasis on different aspects of relationality. For instance, Nigerian-born Ifeanyi Menkiti constructs his theory of personhood upon processual co-becoming, which bonds the individual self with a collective self (Menkiti, 1984; 2004).

10 Posthuman philosophies offer a wide array of reflections, including those focused on relations to others (Ferrando, 2016; 2021), the construction of knowledge (Braidotti, 2019), cyborg and human interactions (Lamola, 2020), and the restructuring on ethics from quantum physics (Barad, 2003).

Metrics

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Claudia Favarato (Author)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.