Polarization and Networked Framing

The Syrian and Ukrainian Refugee Crises on X/Twitter

1 Introduction

The differences in the legal and social treatment of Syrian refugees during the 2015–16 crisis and Ukrainian refugees in 2022 have sparked significant controversy and debate (Karasapan, 2022; Kiyak et al., 2023; Sales, 2023; Traub, 2022; Weber et al., 2023). Specifically, the E.U.’s activation of the “Temporary Protection Directive” for Ukrainians starkly contrasted with the treatment of Syrian refugees, who did not receive similar legal protections (Laitin, 2022). Many citizens have engaged in past and present debates about refugees and refugee policies on social media platforms (SMSs), including X (formerly Twitter), where they formulate their thoughts in tweets, use hashtags, and retweet those they trust or approve to shape the online discourse. This mode of online communication features a vernacular and participatory element that distinguishes it from public debates in mass media, with the circulation of news and opinions on SMSs encouraging numerous citizens to use its functions to affect the communication flow. This phenomenon has created new opportunities for digitally-born alternative media sources and direct political communication opportunities. While these conditions and dynamics can liberate public discussions by introducing previously excluded ideas, they can also propagate destructive polarization, dissonance, conspiracy theories, and misinformation. Therefore, understanding the networked public discussions and networked framing of issues on SMSs is crucial for comprehending modern public discourse on polarizing topics such as refugees and migration.

Previous political communication research about migrants and refugees has traditionally focused on politicians and the media, often employing qualitative and quantitative methods to analyze the content of elite discourse rather than examining vernacular or grassroots dynamics (Lilie et al., 2017; Mertens et al., 2021; Young et al., 2007). Such studies increased in volume after the 2015–16 Syrian refugee crisis. The literature overemphasized the refugees from the Middle East or Africa and the policies and representations concerning them. However, the large influx into Europe of Ukrainians fleeing the 2022 Russian invasion of their homeland remains understudied (el-Nawawy & Elmasry, 2024).

Our study aims to fill these gaps by providing a comparative analysis of public communication networks on X, focusing on polarization, the activity patterns of opposing groups, the influence of elite and non-elite actors, and the networked framing of the Syrian and Ukrainian refugee crises. We identify significant differences in how these crises were framed and discussed on X, revealing increased polarization between opposing groups in 2022. Elite media outlets were less effective at disseminating their messages during the 2022 crisis. Anti-refugee users were particularly likely to promotie non-elite, alternative, digital-born media sources and opinion leaders. Moreover, despite representing a smaller proportion of the network during both crises, anti-refugee users were more active and effective at amplifying their opinions on X in 2022. These shifts led to a change in networked framing on X from a solidarity framing during the Syrian refugee crisis in September 2015 to a skeptic framing about the authenticity of the refugees in March 2022.

Our findings describe the communication networks in these two cases in Germany, highlighting the evolving nature of public discourse on social media. This study contributes to future research on crisis communication and debates about refugees and migrants on SMSs. It also offers insights into improving social media communication to enhance preparedness for future crises.

1.1 Literature Review

X boasts 619 million active monthly users, ranking as the 12th most popular SMS (Statista, 2024). According to a Pew Research Center report, 33% of tweets sent by U.S. adults are political (Bestvater et al., 2022). This highlights X’s crucial role in contemporary public discussions. While elite mass media traditionally shaped public discourse through gatekeeping, agenda-setting, and framing, social media platforms such as X facilitate more decentralized and immediate communication (Bennett & Pfetsch, 2018). This shift enables a broader range of voices and perspectives to participate in public discussions but also poses challenges, including increased polarization, amplification of harmful and exclusionary frames, and the spread of misinformation. X’s many-to-many communication design offers useful affordances that enable users to reach a wider public, facilitating greater engagement, interaction, and the exchange of ideas between diverse audiences. Consequently, it is preferred by political parties and leaders, media institutions, and journalists, as well as new, non-elite political and media actors wanting to engage in public discussions (D’heer & Verdegem, 2014).

Many political communication studies concerning the refugee crises analyze the rhetoric of elite political actors (Mertens et al., 2021) and the representation of refugees on mass media during crises (Lilie et al., 2017) or at critical moments, such as elections (Eberl et al., 2018). Studies primarily focus on populist parties and politicians. Ernst, Esser, and Engesser (2017) demonstrate in their cross-country analysis that populist communication targets mobilizable issues, mainly through social media and newspaper articles, showcasing the successful media strategies of these political actors in Western democracies. Populist politicians are more active and engaged with social media than others, effectively promoting their messages on SMSs. Maurer et al. (2023) find that the German right-wing populist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) uses deliberate provocations – especially targeting migrants – to boost media coverage and public awareness of the party. Maurer et al. (2022) find that German media reports on migration and the refugee crisis more extensively aligned with the consensus from political elites rather than their usual editorial lines. Notably, the media coverage shifted from humanitarian to securitization frames over time (Holzberg et al., 2018). Comparing elite and alternative media in Germany, Nordheim et al. (2019) find that alternative news sources associated with AfD emphasized nationalistic and populist views during the 2015 refugee crisis, mainly ignoring broader international contexts, unlike mainstream media. Overall, these studies focused on analyzing selected elite users and political actors and how they formed discourses about refugees on mass media and SMSs.

Studies analyzing social media communication from a vernacular perspective often focus on specific hashtags or events. Recent political movements have promoted their causes effectively using hashtags, with examples including #Occupy in the US, the Tahir Square protests in Egypt, the Gezi Park movement in Turkey, MeToo, and BLM (Caren et al., 2020). Regarding refugees, researchers have examined the hashtag solidarity activism around #refugeeswelcome during 2015–16 (Barisione et al., 2019). Studies indicate that around September 2015, messages of solidarity with refugees dominated the discourse on X, overshadowing anti-solidarity messages (Hamann & Karakayali, 2016; Weber et al., 2023). Reactionary hashtag counter-publics, such as #refugeesnotwelcome, were also analyzed, but to a lesser extent (Kreis, 2017). These online movements interact with offline efforts, forming post-digital assemblages that impact politicians, media, and public opinion, significantly influencing how public issues are discussed and understood (Åkerlund, 2022; Fletcher et al., 2020).

To analyze polarized online debates from a holistic perspective, some researchers combined multiple hashtags or examined how opposing groups hijack specific hashtags to alter their narratives (Bock & Macdonald, 2019; Graham et al., 2021; Strauß, 2017). However, comprehensive studies that illustrate the overall communication networks on SMSs in the context of refugee crises remain scarce. In the context of refugees in Europe, studies overwhelmingly address the 2015–16 refugee crisis, mainly focusing on migrants from the Middle East and Africa and their impact on politics and public attitudes. The study by Ju-Sung Lee and Adina Nerghes (2018) on social media debates reveals that labels – for example, “refugee” compared to “migrant” – matter for online public attitudes, with “threat” and “agency” being the most impactful dimensions shaping perceptions toward displaced individuals. Studies addressing the Italian X debate on immigration point to highly segregated clusters, where the most influential populist political leaders do not necessarily lead the most prominent clusters, and content diffusion is significantly affected by community structures, resulting in minimal cross-cluster visibility (Kiyak et al., 2024; Vilella et al., 2020). A similar finding is reported regarding Australian X discussions about immigration, where users from polarized clusters strategically engage in both antagonistic and agonistic interactions (Dehghan & Bruns, 2022). Yi Huang (2019) found that ordinary people became key opinion leaders on X, using the platform to create and spread “alternative truths,” thereby challenging traditional media. Gualda and Rebollo (2016) analyzed X data from 2015 to 2016 across multiple European languages, demonstrating discourses ranging from solidarity to xenophobia, reflecting varied national responses to the refugee crisis.

Studies on other refugee populations and their reception, such as Ukrainians, are scarce. The research indicates more consensus among political parties and a more sympathetic and balanced framing of Ukrainian refugees (Bordignon et al., 2022; Iberi & Saddam, 2022; Sales, 2023; Tomsic & Looy, 2022). Furthermore, comparative studies of different refugee crises and public discussions on social media are even more scarce and typically focus on textual content through qualitative or computational methodologies (Cordova et al., 2024; Gebauer, 2023; Iberi & Saddam, 2022; Weber et al., 2023). Particularly relevant to our research, these studies demonstrate that solidarity and anti-solidarity messages on X differed significantly from those in elite media and political discourse. Despite the greater sympathy for Ukrainians and overall support in European countries, discussions about Ukrainian refugees on social media were not always positive, and preexisting polarization on the issue persisted (De Coninck, 2023; Moise et al., 2024; Weber et al., 2023). Finally, in terms of changing polarization in German X, Darius (2022) found that AfD moved from an isolated position in 2017 to integration into the same community as established conservative and liberal parties in 2021, indicating a broader polarization of the German political Twittersphere along traditional left-right lines. However, we do not know how these changes in polarization affected the networked public discussions about refugee crises in 2022.

To fill this lacuna, we analyze the communication network dynamics and networked framing of the Syrian and Ukrainian refugee crises from a holistic perspective. Previous studies have predominantly focused on elite political actors and media representations, often overlooking the vernacular perspective and the reception and spread of news on social media platforms. Those who have studied networked dynamics of public debates during refugee crises have yet to fully use network analysis techniques and trace data to understand how discursive power and networked framing operate in these ad hoc public spheres between opposing groups of users. Public discussion on social media around different refugee crises, particularly comparisons between the 2015 Syrian (N1) and the 2022 Ukrainian (N2) refugee crises, remains to be comprehensively explored.

This study addresses these gaps by responding to the following research questions (all referring to the change from N1 to N2):

- RQ1: How did polarization on retweet networks on X change?

- RQ2: How did the influence of elite media outlets change?

- RQ3: How did the patterns of activity of polarized

communities change? - RQ4: How did opinion leadership of the polarized communities change regarding elites and non-elite users?

- RQ5: How different was the networked framing of these crises on X?

By answering these research questions, we aim to produce a comparative analysis of the evolution of public discourse and engagement on X regarding the Syrian and Ukrainian refugee crises, highlighting changes in polarization, user activity, and the influence of different actors and frames over time.

2 Theoretical Framework

Social media have become a crucial component of the hybrid media environment and contemporary public sphere, marking a new age of communication and public deliberation (Blumler, 2016; Chadwick, 2017). The absence of a unifying principle now characterizes public debates and occurs within the disturbed public spheres of hybrid media systems (Bennett & Pfetsch, 2018; Pfetsch, 2018). This shift is driven by the multiplication of media sources and the empowerment of users to filter or promote new sources, effectively flipping the traditional media-audience dynamic (Bennett & Pfetsch, 2018). On social media, debating citizens form ad hoc issue publics on contentious topics like refugee crises (Bruns & Burgess, 2015). Temporary opposing groups coalesce around specific issues and hashtags, enabled by the interactive nature of SMSs. This general framework highlights how public discourse has become polarized, decentralized, and dynamic, reflecting broader trends in digital communication.

Polarization refers to the process by which public opinion divides and shifts to extremes, often resulting in a lack of common ground between opposing viewpoints (Abramowitz & Saunders, 2008). Polarization is studied extensively in the context of social media (Tucker et al., 2018). While some polarization can enhance political debate, excessive polarization that hinders communication and antagonizes opposing groups can be destructive (Dehghan, 2020; Esau et al., 2023). Although potentially overstated, polarization can have echo chamber effects, further isolating opposing groups (Bruns, 2021; Williams et al., 2015). Studies on polarization often use social network analysis (SNA) to detect opposing groups and analyze their interactions (Esteve Del Valle, 2022; Keuchenius et al., 2021). Network visuals and metrics can quantify polarization and facilitate comparisons (Esteve Del Valle, 2022). Furthermore, destructive polarization causes moderate and neutral voices to lose power and reach in networks, exacerbating the attention afforded to extreme voices (Bruns, 2024). To gauge network polarization, we combine visual analysis with modularity scores and confirm our results by analyzing changes in the influence of established media sources and emergent frames.

In discussions on divisive topics, such as those on X, the ability of elite, reputable media to reach different nodes within the network is crucial. Effective reach would indicate that quality news can permeate all sides of the debate. This study compares interactions between opposing groups during the Syrian and Ukrainian refugee crises and assesses the influence of elite media and political institutions. The term elite refers to individuals and organizations holding significant power in shaping public discourse and policy, such as political parties and mass media (Page & Shapiro, 1992). Early studies of SMSs found elites to be opinion leaders (Di Fraia & Missaglia, 2014). However, recent studies indicate that non-elite users, such as social media influencers and citizen journalists, can also become opinion leaders and achieve popularity and social capital on social media networks (Yi Huang, 2019). Crucially, while older communication models emphasize the primacy of elites, current multi-step communication theory flow places greater emphasis on the interactions between elite and non-elite users in a networked communication ecology to generate influential actors and frames (Ognyanova, 2020). In this context, opinion leaders – whether elite or non-elite – are the users who exhibit the discursive power to create frames that others replicate in and outside their community (Jungherr et al., 2019; Recuero et al., 2019). These users can significantly impact the discourse produced by networked framing (Alexandre et al., 2022; Yoo, 2019).

This new information environment has two effects that we analyze further in the context of refugee crises: patterns of activity in polarized communities and networked framing of the crises. In terms of the former, the communities of users that promote positive or negative opinions and frames about incoming refugees are analyzed in terms of their activity and engagement on X. Previous studies show that right-wing users are better at amplifying their frames, and polarization is asymmetric, with right-wing users tending to be further from the political center in terms of discourse and media preferences (Freelon, 2019; Freelon et al., 2020; González-Bailón et al., 2022). Moreover, studies show that anti-migration political actors in Germany are more successful at using social media to promote their messages (Darius, 2022; Serrano et al., 2019). Conversely, the positive political and public attitudes toward Ukrainians generated a second “European” welcome culture inside and outside of Germany – with AfD’s position uneasy and ambivalent position – creating a complex bundle of effects and forces that condition the public debate about Ukrainian refugees on X (Burchard, 2023; De Coninck, 2023; Gebauer, 2023).

Understanding communication content is crucial for analyzing political polarization, and not all divisions in network structure result from polarization (Garimella, 2018). Networked framing refers to how information is shaped, disseminated, and interpreted within the interconnected structure of digital media networks. It highlights how social media platforms facilitate the dissemination and reinforcement of particular narratives and perspectives, significantly impacting public discourse. This concept builds on traditional framing theory, which focuses on how media outlets construct and present news stories to influence public perception and understanding. In a networked environment, framing becomes a dynamic interaction between citizens, promoting news from trusted sources and opinions from influential users (Meraz & Papacharissi, 2013). Studies such as Benkler et al. (2018) have demonstrated the importance of networked framing for understanding the dynamics of social media influence and the role of elite and non-elite actors in shaping public perceptions of critical issues. This concept is also applied to holistic studies of public debates on SMSs to analyze the battle between the frames of polarized groups (Kermani & Tafreshi, 2022; Walsh, 2023; Walsh & Hill, 2023). Differing from the static nature of mass media frames, networked frames are continuously contested and reinterpreted. Research shows that networked frames provide a dynamic way for citizens to engage in political discourse about refugees through SMSs (Kermani & Tafreshi, 2022; Siapera et al., 2018). The concept of “digital nativism” is proposed to highlight how anti-migrant frames asymmetrically emerge from SMSs through crowdsourced activity in migration debates (Walsh, 2023). This study investigates how digital nativism operated during past and present refugee influxes to facilitate a “level-telling field” about migration in future debates (Gebauer & Sommer, 2022).

3 Methodology

We adopt a mixed-methods approach to investigate the structure and the dynamics of online discourse concerning Syrian and Ukrainian refugees within German-language X retweet networks, combining social media data analysis, social network analysis (SNA), and discourse analysis. We used custom Python scripts for data collection, cleaning, and social media and network analytics (Freelon, 2014/2023). Network visuals have been prepared using Gephi (Bastian et al., 2009).

3.1 Data Collection

The research began with data collection via the X API, using a query targeting various conjugations of “refugee” in German: “Flüchtling OR Flüchtlinge OR Flüchtlingen.” We queried the API twice: first, for the period between August 27, 2015, and October 1, 2015; second, for the period between February 24, 2022, and April 1, 2022. These periods were determined to capture significant mediated events and peak social media communication periods.

Table 1: Tweet and User Counts

|

Syrian-refugee Dataset |

Ukrainian-refugee Dataset |

|

|

All Tweets (Tweets) |

551,873 |

236,034 |

|

Retweets (Retweets) |

281,231 |

145,883 |

|

Users |

96,230 |

88,354 |

3.2 Network Construction and Analysis

We transformed retweet data into social networks, abbreviated as N1 for the Syrian refugee crisis and N2 for the Ukrainian refugee crisis context. Because retweets indicate positive relationships between users, they are used to identify users with similar attributes (Firdaus et al., 2018). Weighted indegree centrality (WIDC) was employed to detect influential users in the dataset. In our network design, a tie connecting X to Y is created when user X retweets a tweet from user Y. The weight of the tie comes from the number of retweets. We refer to users with high WIDC as opinion leaders or influential users and focus on the top ten opinion leaders of different attitudes for practical reasons.

The Louvain community detection algorithm, introduced by Blondel et al. (2008), optimizes network modularity to identify communities within large networks efficiently. Modularity is a measure that quantifies the strength of the division of a network into communities. High modularity indicates a structure where nodes within the same community are more densely connected. Thus, modularity also indicates how divided a network is. We have focused on the ten largest communities to capture the majority of the debate, a common research practice (Freelon, 2020; Freelon et al., 2016).

The automatically identified communities were categorized into three groups – what we refer to as attitudinal communities – based on their stance toward refugees (Syrian or Ukrainian, depending on the case): pro-, anti-, or neutral. The “neutral” label encompassed attitudinal communities whose “top sample” (Gerbaudo, 2016b) contained unopinionated news, mixed opinions, or indecisive cases. For accuracy, we employed two coders and calculated the intercoder reliability. Specifically, we selected the top 20 most retweeted tweets (according to our dataset and the all-time retweet count received from the API) alongside 20 random tweets for each community. After removing duplicates, this process yielded approximately 800 retweets that the reviewers manually coded according to the stance expressed in each retweet. The Cohen’s Kappa score for the Syrian dataset was 0.84; for the Ukrainian dataset, it was 0.94.1

To analyze changing patterns of activity and engagement in networks, we have employed two key metrics. First, the count of intra-community ties (ties within a community) reflects the volume of retweet activity happening between members of the same attitudinal community. The average intra-tie per user in the community, which we refer to as activity, indicates how much, on average, users with the same attitude promoted others with similar attitudes. Second, we refer to the retweet count of individual tweets as their engagement rate and analyze tweets by different communities in N1 and N2 to understand how popular they became during the debates.

Finally, we have visualized the networks using the force-directed layout algorithm Force Atlas 2 (Jacomy et al., 2014). This algorithm simulates a physical system to spatially separate nodes, visually clustering nodes pertaining to the same community while dispersing different communities based on their connectivity. This enables visual analysis of the network structures and relations between nodes (Bruns & Snee, 2022). More information about our SNA and our coding scheme for attitudes appears in the supplementary material (S1, S2, and S3).

3.3 Temporal Networked Frames

We have combined quantitative data analysis to identify the top daily retweets using discourse analysis to explore the networked framing of refugees over time. Our analysis focused on the emergence of new frames and their evolving meanings in the context of real-life events, such as border closures (Kermani & Tafreshi, 2022). The study period was divided into phases to highlight discursive shifts. We employed a top sampling strategy, selecting the top ten daily retweets to examine discursive contention over framing (Gerbaudo, 2016b). We emphasized moments of “digital enthusiasm” within specific attitudinal communities, characterized by heightened activity, to analyze polarization in framing the ongoing crisis (Gerbaudo, 2016a). This section analyzes the evolution of communication content during both crises and investigates how polarization affected the popular daily X conversations. For practical reasons, we did not aim to provide a comprehensive account of all frames but instead focused on the popular retweets to analyze the changing discourse based on what X users found significant or what gained traction. We observed that most changes in the discourse of the popular tweets corresponded to certain real-life events. To present a coherent narrative of these changes, we divided the analyzed timeframes into phases (five for N1 and two for N2). We also visualized the per-community retweet counts daily, annotated with significant events and tweets and with the phases narrated in our analysis. The supplementary material (S4 and S5) includes the coding scheme and its results that guided our discourse analysis, along with some examples of retweets (translated and paraphrased).

4 Results

4.1 Networks and Polarization

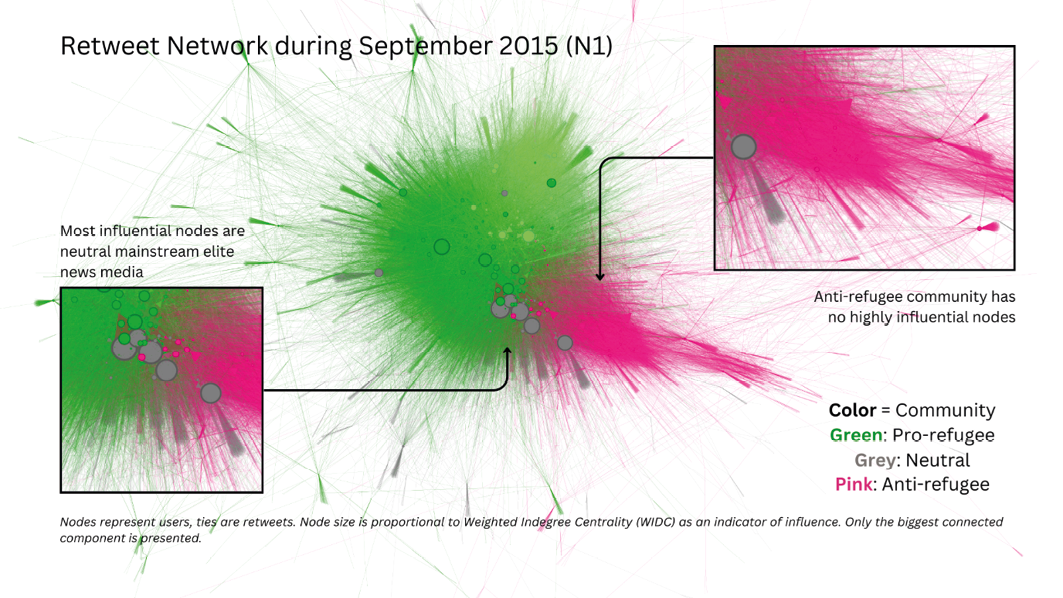

Figures 1 and 2 appear below, annotated for a general overview of the networks N1 and N2. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for both networks.

Figure 1: N1 Network

Figure 2: N2 network

Table 2: Descriptive Network Statistics

|

Syrian (N1) |

Ukrainian (N2) |

|

|

# of nodes |

64,438 |

57,919 |

|

# of edges |

200,070 |

129,426 |

|

Avg. Weighted Degree |

4.36 |

2.50 |

|

Modularity |

0.47 |

0.63 |

The network visualizations reveal a “polarized crowd” structure for both networks, as is often the case for controversial topics (Smith et al., 2014). The N1 retweet network is more extensive than that of N2 in terms of both the number of nodes (users) and the number of ties (retweets). It also has a higher density and average weighted degree, indicating more intense communication during N1 compared to N2. However, its lower modularity score indicates that it is less divided into separate communities than N2. Visual analysis also indicates increasing polarization, a decline in neutral opinion leaders, and the rise of an anti-refugee community from N1 to N2.

4.2 Activity and Engagement

Figure 3 shows the collapsed network structure at the attitudinal level for both networks.

Figure 3: N1 and N2 Community Structure

Note: The graphs above display the community structure of the retweet networks. The nodes represent communities: green for pro-refugee, grey for neutral, and pink for anti-refugee. The numbers in black indicate the size of each community in terms of nodes. The directed ties represent the inter-community retweeting behavior and its volume, while the looping ties represent the intra-community retweeting behavior and its volume. Numbers are rounded and represented in thousands (e.g., 30K for 30,000).

The size of a community provides insight into the popularity of a particular stance within online discussions. Although the neutral community shrank, the anti-refugee community soared from N1 to N2. In N1, the inter-ties between pro-refugee and neutral communities were high compared to the anti-refugee community. Inter-ties are significantly less common in N2 overall.

Table 3: Community Size and Intra-ties in N1 and N2

|

Syrian Related (N1) |

||||

|

Size |

Size % |

Intra-ties |

Avg. Intra-tie |

|

|

Pro-refugee |

30,252 |

63 |

143,822 |

4.75 |

|

Neutral/Mixed |

9,544 |

20 |

16,704 |

1.75 |

|

Anti-refugee |

7,863 |

16 |

28,865 |

3.67 |

|

Ukrainian Related (N2) |

||||

|

Size |

Size % |

Intra-ties |

Avg. Intra-tie |

|

|

Pro-refugee |

30,144 |

64 |

57,707 |

1.91 |

|

Neutral/Mixed |

5,194 |

11 |

8,879 |

1.71 |

|

Anti-refugee |

11,510 |

23 |

50,157 |

4.36 |

Note: Table 3 shows the attitudinal groups, size, internal retweet activity, and the average intra-tie per user.

As expected in polarized discussions, activity within opposing user communities is higher compared to neutral/mixed communities in both N1 and N2. The neutral communities in N1 and N2 exhibit similar activity patterns, likely due to the topography of these subgraphs resembling “broadcast networks,” characterized by only a few hubs that other members retweet without much intensity or interaction between them (Smith et al., 2014).

The pro-refugee community demonstrated the strongest per-user activity in retweeting behavior in N1, responding to the ongoing humanitarian crisis. However, given pro-Ukrainian refugee policies in Germany and Europe, users with a pro-attitude might have found fewer reasons to engage in retweeting in N2. Despite this, the size of this community remained the same between 2015 and 2022, indicating a decrease in motivation rather than size.

In contrast, the anti-refugee community expanded and increased internal connections and user activity both in absolute numbers and on average. This shift indicates that digital nativism has strengthened its influence on X networks since 2015. Moreover, despite remaining about one-third the size of the pro-refugee community, the anti-refugee community engaged in comparable internal retweeting behavior, indicating their effectiveness at challenging mainstream media narratives and policies on X in N2.

Figure 4: Log-Scaled Retweet Frequencies by Attitudinal Community (2015 vs 2022)

Retweet count by attitude (Figure 4) provides insight into the popularity of different discourses at the level of tweets in both crises. The figure indicates a shift in the popularity of tweets within different attitudinal communities from 2015 to 2022. While messages from pro-refugee users were more dominant in 2015, messages from anti-refugee users gained substantial traction by 2022. The engagement in pro-refugee retweets remained constant, with a slight decrease in very-high-retweet tweets in 2022. In 2015, Neutral/Mixed tweets showed a pattern resembling pro-refugee tweets but with generally fewer high-retweet tweets. However, Neutral/Mixed tweets are noticeably less both in volume and popularity in 2022. The highest concentration is below 100 retweets, indicating less viral content compared to 2015. Tweets by anti-refugee users in 2015 were fewer and did not reach the same high retweet counts as the pro-refugee tweets. In contrast, tweets from anti-refugee users in 2022 showed a significant increase in retweet counts, even surpassing the number of pro-refugee tweets at the higher end of the spectrum (tweets with over 100 retweets). This suggests a stronger presence and more popular tweets by the anti-refugee community in 2022. This shift is evidence of growing polarization, with the anti-refugee community becoming more vocal and influential on social media. Results of the analysis of activity and engagement patterns provide support for the increasing amplification of anti-refugee discourse.

4.3 Influential Users

Table 4: Influential users in N1

|

# |

Pro-refugee |

Neutral/Mixed |

Anti-Refugee |

||||||

|

Type |

Elite |

WIDC |

Type |

Elite |

WIDC |

Type |

Elite |

||

|

1 |

Media |

1 |

4,644 |

Media |

1 |

5,731 |

Media |

1 |

1,282 |

|

2 |

Media |

1 |

3,799 |

Media |

1 |

4,489 |

- |

- |

1,216 |

|

3 |

Media |

1 |

3,777 |

Media |

1 |

3,752 |

Media |

1 |

1,167 |

|

4 |

Org |

1 |

3,637 |

Media |

1 |

3,603 |

Media |

1 |

1,145 |

|

5 |

Ind |

0 |

2,531 |

Media |

1 |

3,452 |

Media |

1 |

1,013 |

|

6 |

Media |

1 |

2,451 |

Media |

1 |

1,128 |

Ind. |

1 |

622 |

|

7 |

Media |

1 |

2,179 |

Media |

1 |

953 |

Media |

1 |

610 |

|

8 |

Media |

1 |

1,970 |

Media |

1 |

905 |

- |

- |

568 |

|

9 |

Media |

1 |

1,812 |

Media |

1 |

803 |

Media |

1 |

520 |

|

10 |

- |

- |

1,709 |

Media |

1 |

617 |

Media |

1 |

490 |

Table 5: Influential users 2022

|

# |

Pro-refugee |

Neutral/Mixed |

Anti-Refugee |

||||||

|

Type |

Elite |

WIDC |

Type |

Elite |

WIDC |

Type |

Elite |

WIDC |

|

|

1 |

Other |

1 |

4,177 |

Media |

1 |

867 |

Media |

0 |

3,780 |

|

2 |

Media |

1 |

3,839 |

Media |

1 |

865 |

Ind |

0 |

2,802 |

|

3 |

Media |

0 |

1,141 |

Media |

1 |

598 |

Politic |

1 |

1,747 |

|

4 |

Ind |

0 |

975 |

Media |

1 |

497 |

Media |

0 |

1,559 |

|

5 |

Ind |

0 |

896 |

Media |

1 |

469 |

Ind |

0 |

1,377 |

|

6 |

- |

- |

867 |

Media |

1 |

465 |

Ind |

0 |

1,350 |

|

7 |

Ind |

0 |

819 |

Media |

1 |

443 |

Media |

1 |

1,170 |

|

8 |

Media |

1 |

806 |

Media |

1 |

403 |

Ind |

0 |

1,121 |

|

9 |

Media |

1 |

781 |

Media |

1 |

318 |

Politic |

1 |

908 |

|

10 |

Politic |

1 |

694 |

Media |

1 |

259 |

Media |

0 |

845 |

Tables 4 and 5 highlight the changes in influential users during the refugee crises of 2015 and 2022. In 2015, during the Syrian refugee crisis, the elite media dominated the discourse, with most influential users (highest WIDC in both networks) coming from established media outlets. However, by 2022, during the Ukrainian refugee crisis, there was a notable increase in the influence of individual users without traditional media affiliations, especially within the anti-refugee community. These users, often social media influencers, exhibited low journalistic standards and a clear anti-refugee bias.

The shift from elite media dominance in 2015 to a more diversified set of influential voices in 2022 indicates the growing power of social media to shape public opinion and the rise of non-elite sources in polarizing debates. Politicians also emerged as significant influencers in 2022, demonstrating how politicians use social media to directly engage with their audience. The most retweeted politicians appeared on opposite ends of the political spectrum, with one from Die Linke, in the pro-refugee community, and two from AfD, in the anti-refugee community, highlighting the promotion of polarizing voices in online debates.

Finally, not only did the influence of elite media institutions in N2 decrease, but so did their reach in the networks, reflecting a broader trend toward fragmented information sources. We manually checked five elite media sources (visualized in Figure 5) that appeared among the top ten in both periods to confirm. In 2015, these sources were connected to 3,175 users, including 2,325 pro-refugee and 845 anti-refugee nodes, representing 6.66% of the network. By 2022, their reach had decreased to 577 users, including 457 pro-refugee and 115 anti-refugee nodes, comprising only 1.24% of the network.

Figure 5: Elite Media Reach in N1 and N2

Note: Five dark grey nodes represent elite media in both N1 and N2. The nodes that retweeted them are colored green if they belong to the pro-refugee community and pink if they belong to the anti-refugee community. The rest of the nodes are colored light grey. Spiegel Online rebranded to Der Spiegel in 2020.

4.4 Networked Framing

Figure 6: Daily Retweet Counts by Attitudinal Community (Syria, N1)

Note: Daily Retweet Count for the Syrian Refugee Crisis retweet network per attitudinal community (colors). The timeline is divided into 5 phases (P) where changes in the discourse are observed. Annotations indicate important developments and viral tweet topics.

#RefugeesWelcome and messages of solidarity marked the first phase (P1) of the X refugee discourse (Figure 6). On September 27, news about the tragic deaths of refugees in a truck in Austria shook German-language X, prompting an outpouring of solidarity messages. Overall, retweet numbers were high, with tweets mainly focusing on calls for solidarity with refugees, celebrating solidarity efforts, countering anti-refugee narratives, and sharing news about refugees. After Merkel’s “Wir schaffen das” statement on September 31, state institutions such as local police departments also started contributing to solidarity efforts by sharing information on X.

However, when Hungary started to stop refugees from traveling further into Europe on September 2 (P2), the discourse temporarily shifted from solidarity to frames about the suffering of refugees and criticisms of Hungary. By September 4, most of the top daily retweets returned to information about supporting the refugees. They remained overwhelmingly popular in terms of retweets, boosting the visibility of the solidarity frames and pro-refugee opinion leaders.

On September 9 (P3), for the first time, neutral and anti-refugee frames represented the top retweeted statements. Initially, Welt ran a story claiming Salafists were organizing among the refugees2 , followed by the Frankfurter Allgemeine (the next day) with a story that claimed the Gulf states wanted to build 200 mosques in Germany.3 This story went viral, dominating the top retweets and enjoying popularity beyond Germany, boosting the anti-refugee community. Top retweets returned to solidarity framing in the following days, though a more neutral/mixed tone persisted among popular tweets until September 13.

On September 13 (P4), Germany reinstated border controls, a move criticized by solidarity activists in the pro-refugee community. The solidarity frame then evolved to include sharing routes to cross borders, information about whereabouts, avoiding the police, and offering legal and other help to activists. Thus, the solidarity frame gained a new meaning due to the closed borders but also became marginalized and less trending. Tweets from the pro-refugee community subsequently started to decline in popularity, never reaching similar levels again. Another significant discursive contestation arose around Oktoberfest on September 13 and the following days, with pro-refugee users in Germany particularly criticizing Horst Seehofer, Minister-President of Bavaria, for his comments on making Oktoberfest safe by halting incoming refugees, leading to the hashtag #Oktoberfestung (October fortress) going viral.

On September 16 and 17, a heated online debate reached high retweet numbers. The tabloid newspaper Bild’s campaign “Wir Helfen” (We help), which had started earlier (on September 1), caused controversy when FC St. Pauli, a historically leftist football team, boycotted its promotion in Bundesliga.4 The campaign was deemed hypocritical by the team and many football fans due to the advertising nature of the campaign and the newspaper’s bad record on refugee issues. St. Pauli supporters promoted the hashtag #BildNotWelcome. This controversy generated the highest daily activity in the neutral/mixed/media community. While the top retweets during this debate were primarily critical of Bild and pro-refugee, they included many responses and replies that were part of a broader conversation, including pro-Bild, satirical, and anti-refugee messages. After this peak caused by the Bild controversy, the volume of messages in the overall conversation dipped.

On September 19, the final phase (P5) started with top retweets covering attacks by anti-refugee groups against refugees and refugee centers or activists supporting refugees. This persisted until the end of the analysis period. All the popular tweets about the attacks were either news, criticisms, or warnings about the attacks. The attack frames replaced the messages of solidarity, as it was one or the other in the top retweets in this phase. As the initial hype passed and the physical and legal issues threatened solidarity activists, the topic lost popularity on X, and the difference between daily retweets by different groups became even more pronounced by the end of September.

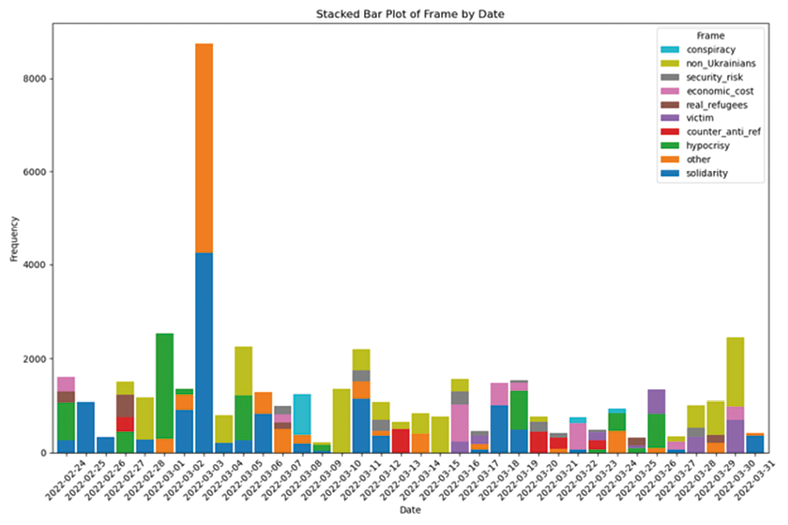

Figure 7: Daily Retweet Counts by Attitudinal Community (Ukraine, N2)

Note: Daily Retweet Count for the Ukrainian Refugee Crisis retweet network per attitudinal community (colors). The timeline is divided into 2 phases (P) where changes in the discourse are observed. Annotations indicate important developments and viral tweet topics.

We found the daily trending tweet content in N2 to be more complex and multidimensional due to differing attitudes toward different refugee populations and the employment of differing rhetorical strategies. Some popular tweets were clearly against the Ukrainian refugees (21%). Some others were pro-Ukrainian refugees, claiming they were the “real” refugees, unlike others (5%). Some tweets, while not directly opposing solidarity and aid for refugees, framed the influx as a security risk (6%). Many of the top tweets were conveniently ambiguous about their intended message (21%). They mostly framed the issue to suggest that most incoming refugees were migrants from third countries. The images and videos shared in this framing were of dark-skinned men. These messages often straddled the line between plausible deniability and satire. While they were clearly absurd and humorous, such as out-of-context images of the foreign minister with African refugees presented as Ukrainian, they had clear racist undertones. They provided justifications for opposition to aiding Ukrainian refugees and hindering government efforts to do so for receptive audiences to promote and share. This framing was adopted by some AfD politicians in viral tweets. Finally, in even more extreme cases, several popular tweets (3%) propagated conspiracies, suggesting that refugee crisis regulations (alongside climate and COVID regulations) were government conspiracies to replace the German population with outsiders. Overall, more varied frames and intricate attitudes were visible among the top daily retweets in N2. However, the general attitude was positive toward Ukrainians, and most top retweets were unambiguously supportive of Ukrainian refugees (66%).

The start of the war marked the first phase of discourse (P1), characterized by sympathy toward refugees (Figure 7). The main message frames were efforts and information about ongoing solidarity, followed by significantly popular tweets criticizing the hypocrisy of the unequal treatment between African and Middle Eastern refugees and Ukrainian refugees. The third most common framing, which persisted into the next phase, concerned rumors of non-Ukrainian migrants among Ukrainian refugees.

On March 4, the discourse (P2) shifted, with popular tweets sharing and commenting on a news story from NZZ featuring a section titled “Federal police union concerned about African migrants among Ukrainian refugees.” From this point onward, at least one of the top ten daily retweets frequently expressed concerns about non-Ukrainian refugees exploiting the situation. We have already discussed the “non-Ukrainians” among Ukrainians framing above. Solidarity efforts remained the second most retweeted issue but appeared less frequently, possibly due to the state aid already received by Ukrainian refugees. A third prominent frame was the economic cost of refugees, with welfare chauvinistic opinions criticizing spending on refugees, blaming the poor economy on them, or claiming that refugees receive more aid or pensions than German citizens. The second most common pro-refugee frame during this last phase was victimhood, with popular tweets (similarly to their N1 counterparts) highlighting the plight and suffering of Ukrainians.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

Our study indicates that the distance between opposing camps regarding refugee crises on social media has increased since 2015 (RQ1). Communication activity between different attitudinal groups has decreased, and the influence of moderate voices, such as elite media institutions with journalistic standards, has also diminished in N2 compared to N1 (R2). Despite the general sympathy toward Ukrainian refugees in public, predetermined opinions about refugees primarily drive the polarized social media network activity and framing of the crises. While not all polarization is harmful, the form observed in N2 shows signs of being destructive to healthy democratic debate by undermining dialogue and exacerbating divisions between opposing sides (Esau et al., 2023). This finding highlights the need for strategies to bridge gaps and foster inclusive discussion (Bail, 2022).

In platforms where algorithms dictate what citizens see as reliable news and opinions, effectively amplifying one’s frames is a condition for discursive power. Despite their smaller numbers and lack of mainstream and established media support, the anti-refugee community effectively harnessed this power in 2022 by adopting specific framing strategies (RQ3). Their frames achieved daily prominence through grassroots efforts. In contrast, pro-refugee voices and discourses were less active and engaged, despite representing a larger population. Our findings align with the existing literature on discursive power imbalances on SMSs (Freelon et al., 2020; González-Bailón et al., 2022).

While both polarized communities featured more non-elite opinion leaders in N2 compared to N1, the anti-refugee group promoted more non-elite ones (RQ4). The relatively low quality of news from these sources made them more susceptible to manipulation and disinformation than elite media. Furthermore, highly biased and partial reporting of this kind can amplify the dissonant logic of the polarized publics, worsening the problem.

Networked framing of the refugee crises significantly differed in N1 and N2 (RQ5). The frames of solidarity with refugees were considerable in N1 but lost their popularity with increasing regulation and physical violence. In N2, apart from clearly pro or anti-Ukrainian refugee framings, there was also significant indirect opposition to refugees. This frame was promoted by anti-refugee opinion leaders, including some AfD politicians, to cast doubt and skepticism on the deservingness of Ukrainians for the help they received without directly demonizing them. We interpret this as a discursive strategy designed to attract anti-refugee voters without alienating the public. Additionally, networked framing in N2 was more complex and less clearly delineated along the left-right divide. For instance, some popular tweets reframed Ukrainians as “real” refugees (as opposed to others who are considered illegitimate) and reinterpreted the populist political identity, such as praising Hungary for taking thousands of “real” refugees (Loner, 2023). In short, pro-refugee frames dominated most of N1, producing a fragile but powerful viral effect. The networked framing during N2 was less intense but also significantly more divided and multifaceted compared to N1.

In conclusion, the current state of public communication on SMSs fosters a dissonant space where various social forces and movements compete to promote their messages by sidelining rational deliberation and traditional editorial processes. While social media can democratize public debate, it also risks entrenching divisive and extreme viewpoints and fostering social closure and hardline policies. Digital nativism as networked anti-refugee framing is an essential factor in mainstreaming anti-refugee and migrant positions in politics and media (Walsh, 2023). However, the prevalence of digital nativism makes it harder to be prepared to discuss and manage future crises (Dreher & Voyer, 2015). This exacerbation is the product of not only technology but also current social conditions and online vernacular culture. This means that it is not inevitable, and there is potential for pro-refugee actors to reconfigure their tactics to counteract nativist discourses.

5.1 Limitations

Our analysis carries inherent limitations. First, the Russian invasion fundamentally differs from the Syrian Civil War in terms of the legal treatment of affected populations and the cultural and religious differences between Ukrainians and Syrians, making direct comparisons challenging. Second, although “refugee” was the most used term in both periods on X, the specific terminology varied. “Migrant” was often applied to Syrians and “displaced” (‘Vertriebene’) to Ukrainians. Although “Vertriebene” is not widely used in online discussions, “migrant” is and carries a specific derogatory meaning, often preferred by anti-refugee attitudinal users (Nerghes & Lee, 2018). Third, our data collection is limited by X API constraints. In particular, our 2015 dataset could be missing data and data features that are dependent on their status at the time of collection. Finally, bot detection could be valuable to future studies to gauge the pervasiveness of inauthentic content amplification. Given these limitations, it is important to clarify that our study does not aim to compare the degree of opposition or hate faced by different refugee populations online. Instead, it focuses on analyzing the evolving nature of polarization on X.

5.2 Future Studies

Future studies can expand on this analysis by incorporating signed networks to understand nuanced user relationships, such as positive and negative interactions (Keuchenius et al., 2021). Additionally, employing temporal network analysis can provide a more granular understanding of networked framing over time (Friemel & Neuberger, 2023). Cross-platform analyses should also investigate how different platform affordances impact the formation and dynamics of networked publics, fringe publics, and niche platforms (Peeters et al., 2023; Rogers, 2018). Finally, the conceptual framework and mixed-method approaches proposed in this study can be applied to other forms of migration, such as climate migrants and skilled workers, to examine the public debates and communication patterns surrounding these groups (Dreher & Voyer, 2015).

References

Abramowitz, A. I., & Saunders, K. L. (2008). Is polarization a myth? The Journal of Politics, 70 (2), 542–555. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381608080493

Åkerlund, M. (2022). Far right, right here: Interconnections of discourse, platforms, and users in the digital mainstream [PhD Dissertation, Umeå University]. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-191942

Alexandre, I., Jai-sung Yoo, J., & Murthy, D. (2022). Make tweets great again: Who are opinion leaders, and what did they tweet about Donald Trump? Social Science Computer Review, 40 (6), 1456–1477. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393211008859

Bail, C. (2022). Breaking the social media prism: How to make our platforms less polarizing. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691246499

Bail, C. A. (2014). The cultural environment: Measuring culture with big data. Theory and Society, 43 (3), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-014-9216-5

Barisione, M., Michailidou, A., & Airoldi, M. (2019). Understanding a digital movement of opinion: The case of #RefugeesWelcome. Information, Communication & Society, 22 (8), 1145–1164. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1410204

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford University Press.

Bennett, W. L., & Pfetsch, B. (2018). Rethinking political communication in a time of disrupted public spheres. Journal of Communication, 68 (2), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqx017

Bestvater, S., Shah, S., Gonzalo Rivero, & Smith, A. (2022, June 16). Politics on Twitter: One-third of tweets from U.S. adults are political. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2022/06/16/politics-on-twitter-one-third-of-tweets-from-u-s-adults-are-political/

Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R., & Lefebvre, E. (2008). Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2008(10). http://arxiv.org/abs/0803.0476

Blumler, J. G. (2016). The fourth age of political communication: Politiques de Communication, 6 (1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.3917/pdc.006.0019

Bock, J.-J., & Macdonald, S. (Eds.). (2019). Refugees welcome? Difference and diversity in a changing Germany (1st ed.). Berghahn Books.

Bordignon, F., Diamanti, I., & Turato, F. (2022). Rally ‘round the Ukrainian flag. The Russian attack and the (temporary?) suspension of geopolitical polarization in Italy. Contemporary Italian Politics, 14 (3), 370–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2022.2060171

Bruns, A. (2021). Echo chambers? Filter bubbles? The misleading metaphors that obscure the real problem. In M. Pérez-Escolar & J. M. Noguera-Vivo, Hate Speech and Polarization in Participatory Society (1st ed., pp. 33–48). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003109891-4

Bruns, A. (2024, April 25). Dynamics of Destructive Polarisation in Mainstream and Social Media: The Case of the Australian Voice to Parliament Referendum. Indicators of Social Cohesion in Social and Online Media, Hamburg. https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/dynamics-of-destructive-polarisation-in-mainstream-and-social-media-the-case-of-the-australian-voice-to-parliament-referendum/267519205

Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2015). The use of Twitter hashtags in the formation of ad hoc publics. In Hashtag publics: The power and politics of discursive networks (Vol. 103, pp. 13–27).

Bruns, A., & Snee, H. (2022). How to visually analyse networks using Gephi. In SAGE Research Methods: Doing Research Online. SAGE Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529609752

Burchard, H. von der. (2023, July 30). German far right picks EU lead candidate, wants European anti-migrant ‘fortress.’ POLITICO. https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-alternative-fur-deutschland-european-parliament-election-maximilian-krah-migration/

Caren, N., Andrews, K. T., & Lu, T. (2020). Contemporary social movements in a hybrid media environment. Annual Review of Sociology, 46 (1), 443–465. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-121919-054627

Chadwick, A. (2017). The hybrid media system (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190696726.001.0001

Conover, M., Ratkiewicz, J., Francisco, M., Goncalves, B., Menczer, F., & Flammini, A. (2011). Political polarization on Twitter. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 5 (1), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v5i1.14126

Cordova, G., Palla, L., Sustrico, M., & Rossetti, G. (2024). I like you if you are like me: How the Italians’ opinion on Twitter about migrants changed after the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian conflict. In H. Cherifi, L. M. Rocha, C. Cherifi, & M. Donduran (Eds.), Complex Networks & Their Applications XII (pp. 183–193). Springer Nature Switzerland.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-53472-0_16

Darius, P. (2022). Who polarizes Twitter? Ideological polarization, partisan groups and strategic networked campaigning on Twitter during the 2017 and 2021 German Federal elections “Bundestagswahlen.” Social Network Analysis and Mining, 12 (1). Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-022-00958-w

De Coninck, D. (2023). The refugee paradox during wartime in Europe: How Ukrainian and Afghan refugees are (not) alike. International Migration Review, 57 (2), 578–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183221116874

Dehghan, E. (2020). Networked discursive alliances: Antagonism, agonism, and the dynamics of discursive struggles in the Australian Twittersphere [PhD, Queensland University of Technology]. https://doi.org/10.5204/thesis.eprints.174604

Dehghan, E., & Bruns, A. (2022). The dynamics of polarisation in Australian social media: The case of immigration discourse. In D. Palau-Sampio, G. López García, & L. Iannelli (Eds.), Contemporary Politics, Communication, and the Impact on Democracy (pp. 57–73). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-8057-8.ch004

D’heer, E., & Verdegem, P. (2014). An intermedia understanding of the networked Twitter ecology. In B. Pătruţ & M. Pătruţ (Eds.), Social Media in Politics: Case Studies on the Political Power of Social Media (pp. 81–96). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04666-2_6

Di Fraia, G., & Missaglia, M. C. (2014). The use of Twitter in 2013 Italian political election. In B. Pătruţ & M. Pătruţ (Eds.), Social Media in Politics: Case Studies on the Political Power of Social Media (pp. 63–77). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04666-2_5

Dreher, T., & Voyer, M. (2015). Climate refugees or migrants? Contesting media frames on climate justice in the Pacific. Environmental Communication, 9 (1), 58–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2014.932818

Eberl, J.-M., Meltzer, C. E., Heidenreich, T., Herrero, B., Theorin, N., Lind, F., Berganza, R., Boomgaarden, H. G., Schemer, C., & Strömbäck, J. (2018). The European media discourse on immigration and its effects: A literature review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 42 (3), 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2018.1497452

el-Nawawy, M., & Elmasry, M. H. (2024). Worthy and unworthy refugees: Framing the Ukrainian and Syrian refugee crises in elite American newspapers. Journalism Practice, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2024.2308527

Ernst, N., Engesser, S., Büchel, F., Blassnig, S., & Esser, F. (2017). Extreme parties and populism: An analysis of Facebook and Twitter across six countries. Information, Communication & Society, 20 (9), 1347–1364. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1329333

Esau, K., Choucair, T., Vilkins, S., Svegaard, S., Bruns, A., & Lubicz, C. (2023, May 25). Destructive Political Polarization in the Context of Digital Communication – A Critical Literature Review and Conceptual Framework. 73rd Annual ICA Conference, Toronto. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/238775/

Esteve Del Valle, M. (2022). Homophily and polarization in twitter political networks: A cross-country analysis. Media and Communication, 10 (2). https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i2.4948

Firdaus, S. N., Ding, C., & Sadeghian, A. (2018). Retweet: A popular information diffusion mechanism – A survey paper. Online Social Networks and Media, 6 , 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.osnem.2018.04.001

Fletcher, R., Cornia, A., & Nielsen, R. K. (2020). How polarized are online and offline news audiences? A comparative analysis of twelve countries. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25 (2), 169–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219892768

Freelon, D. (2019). Tweeting left, right & center: How users and attention are distributed across Twitter. John S. & James L. Knight Foundation. https://knightfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/KF-Twitter-Report-Part1-v6.pdf

Freelon, D. (2020). Partition-specific network analysis of digital trace data: Research questions and tools. In B. Foucault Welles & S. González-Bailón (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Networked Communication (pp. 89–110). Oxford University Press.

Freelon, D. (2023). TSM [Python]. https://github.com/dfreelon/TSM (Original work published 2014)

Freelon, D., Marwick, A., & Kreiss, D. (2020). False equivalencies: Online activism from left to right. Science, 369(6508), 1197–1201. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb2428

Freelon, D., McIlwain, C. D., & Clark, M. D. (2016). Beyond the hashtags: #Ferguson, #Blacklivesmatter, and the online struggle for offline justice. Center for Media & Social Impact. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2747066

Friemel, T. N., & Neuberger, C. (2023). The public sphere as a dynamic network. Communication Theory, 33 (2–3), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtad003

Garimella, K. (2018). Polarization on Social Media [PhD Thesis, Aalto University]. https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi:443/handle/123456789/29708

Gebauer, C. (2023). German welcome culture then and now. How crisis narration can foster (contested) solidarity with refugees. DIEGESIS, 12 (2), Article 2. https://www.diegesis.uni-wuppertal.de/index.php/diegesis/article/view/488

Gebauer, C., & Sommer, R. (2022). Beyond vicarious storytelling: How level telling fields help create a fair narrative on migration (OPPORTUNITIES, p. 27). University of Wuppertal.

Gerbaudo, P. (2016a). Constructing public space: Rousing the Facebook crowd: Digital enthusiasm and emotional contagion in the 2011 protests in Egypt and Spain. International Journal of Communication, 10 .

https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/3963

Gerbaudo, P. (2016b). From data analytics to data hermeneutics. Online political discussions, digital methods and the continuing relevance of interpretive approaches. Digital Culture & Society, 2 (2), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.14361/dcs-2016-0207

Ghadakpour, N. (2022, July 5). Treat Syrian refugees the same as Ukrainians, says UN commission chair. Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2022/07/04/syrian-and-ukrainian-refugees-should-receive-same-treatment-says-un-commission-chair

González-Bailón, S., D’Andrea, V., Freelon, D., & De Domenico, M. (2022). The advantage of the right in social media news sharing. PNAS Nexus, 1 (3). https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac137

Graham, T., Bruns, A., Angus, D., Hurcombe, E., & Hames, S. (2021). #IStandWithDan versus #DictatorDan: The polarised dynamics of Twitter discussions about Victoria’s COVID-19 restrictions. Media International Australia, 179(1), 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X20981780

Gualda, E., & Rebollo, C. (2016). The refugee crisis on Twitter: A diversity of discourses at a European crossroads. Journal of Tourism, Sustainability and Well-Being, 4 (3), 199–212.

Hamann, U., & Karakayali, S. (2016). Practicing Willkommenskultur: Migration and solidarity in Germany. Intersections, 2 . https://doi.org/10.17356/ieejsp.v2i4.296

Holzberg, B., Kolbe, K., & Zaborowski, R. (2018). Figures of crisis: The delineation of (un)deserving refugees in the German media. Sociology, 52 (3), 534–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518759460

Iberi, D., & Saddam, R. (2022). Media framing of refugees: Juxtaposing Ukrainian and African refugees in the wake of Russia-Ukraine conflict. Journal of Central and Eastern European African Studies, 2 (4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.59569/jceeas.2022.2.4.115

Jacomy, M., Venturini, T., Heymann, S., & Bastian, M. (2014). ForceAtlas2, a continuous graph layout algorithm for handy network visualization designed for the Gephi software. PLoS ONE, 9 (6), e98679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098679

Jungherr, A., Posegga, O., & An, J. (2019). Discursive power in contemporary media systems: A comparative framework. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 24 (4), 404–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219841543

Karasapan, O. (2022, June 21). Forcibly displaced Ukrainians: Lessons from Syria and beyond. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2022/06/21/forcibly-displaced-ukrainians-lessons-from-syria-and-beyond/

Kermani, H., & Tafreshi, A. (2022). Walking with Bourdieu into Twitter communities: An analysis of networked publics struggling on power in Iranian Twittersphere. Information, Communication & Society, 26 (8), 1653–1674. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.2021267

Keuchenius, A., Törnberg, P., & Uitermark, J. (2021). Why it is important to consider negative ties when studying polarized debates: A signed network analysis of a Dutch cultural controversy on Twitter. PLOS ONE, 16 (8), e0256696. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256696

Kiyak, S., Coninck, D. D., Mertens, S., & d’Haenens, L. (2023). Exploring the German-Language Twittersphere: Network analysis of discussions on the Syrian and Ukrainian refugee crises. In B. Berendt, M. Krzywdzinski, & E. Kuznetsova (eds.), Proceedings of the Weizenbaum Conference 2023: AI, Big Data, Social Media, and People on the Move (pp. 46–58). Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society - The German Internet Institute. https://doi.org/10.34669/wi.cp/5.5

Kiyak, S., Coninck, D. D., Mertens, S., & d’Haenens, L. (2024). From the Syrian to Ukrainian refugee crisis: Tracing the changes in the Italian Twitter discussions through network analysis. Communications.

https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2024-0023

Kreis, R. (2017). #refugeesnotwelcome: Anti-refugee discourse on Twitter. Discourse & Communication, 11 (5), 498–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481317714121

Lilie, C., Myria, G., & Rafal, Z. (2017). The European “migration crisis” and the media: A cross-European press content analysis. London School of Economics and Political Science. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/84670

Loner, E. (2023). Enemies and friends. The instrumental social construction of populist identity through twitter in Italy at the time of COVID-19. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 10 (2), 279–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/23254823.2022.2125421

Maurer, M., Haßler, J., Kruschinski, S., & Jost, P. (2022). Looking over the channel: The balance of media coverage about the “refugee crisis” in Germany and the UK. Communications, 47 (2), 219–240. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2020-0016

Maurer, M., Jost, P., Schaaf, M., Sülflow, M., & Kruschinski, S. (2023). How right-wing populists instrumentalize news media: Deliberate provocations, scandalizing media coverage, and public awareness for the alternative for Germany (Afd). The International Journal of Press/Politics, 28 (4), 747–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612211072692

Mertens, S., de Coninck, D., & d’Haenens, L. (2021). The Twitter Debate on Immigration in Austria, Germany, Hungary, and Italy: Politicians’ articulations of the discourses of openness and closure. Deliverable 4.7. KU Leuven: OPPORTUNITIES project 101004945 – H2020.

Moise, A. D., Dennison, J., & Kriesi, H. (2024). European attitudes to refugees after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. West European Politics, 47 (2), 356–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2229688

Nerghes, A., & Lee, J.-S. (2018). The refugee/migrant crisis dichotomy on Twitter: A network and sentiment perspective. Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Web Science, 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1145/3201064.3201087

Nordheim, G. von, Müller, H., & Scheppe, M. (2019). Young, free and biased: A comparison of mainstream and right-wing media coverage of the 2015–16 refugee crisis in German newspapers. Journal of Alternative & Community Media, 4 (1), 38–56. https://doi.org/10.1386/joacm_00042_1

Ognyanova, K. (2020). Rebooting mass communication: Using computational and network tools to rebuild media theory. In B. Foucault Welles & S. González-Bailón (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Networked Communication (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190460518.013.5

Page, B. I., & Shapiro, R. Y. (1992). The Rational Public: Fifty Years of Trends in Americans’ Policy Preferences. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/R/bo3762628.html

Peeters, S., Willaert, T., Tuters, M., Beuls, K., Van Eecke, P., & Van Soest, J. (2023). A fringe mainstreamed, or tracing antagonistic slang between 4chan and Breitbart before and after Trump. In R. Rogers (ed.), The propagation of misinformation in social media. Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.5117/9789463720762_ch08

Pfetsch, B. (2018). Dissonant and disconnected public spheres as challenge for political communication research. Javnost - The Public, 25 (1–2), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2018.1423942

Recuero, R., Zago, G., & Soares, F. (2019). Using social network analysis and social capital to identify user roles on polarized political conversations on Twitter. Social Media + Society, 5 (2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119848745

Rogers, R. (2018). Digital methods for cross-platform analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media (pp. 91–108). SAGE Publications Ltd.

https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473984066

Rogers, R. (2019). Doing digital methods (1st edition). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Sales, M. I. (2023). The refugee crisis’ double standards: Media framing and the proliferation of positive and negative narratives during the Ukrainian and Syrian crises (Policy Brief 129; Euromesco). European Institute of Mediterranean. https://www.euromesco.net/publication/the-refugee-crisis-double-standards-media-framing-and-the-proliferation-of-positive-and-negative-narratives-during-the-ukrainian-and-syrian-crisis/

Serrano, J. C. M., Shahrezaye, M., Papakyriakopoulos, O., & Hegelich, S. (2019). The rise of Germany’s AfD: A social media analysis. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Social Media and Society, 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1145/3328529.3328562

Siapera, E., Boudourides, M., Lenis, S., & Suiter, J. (2018). Refugees and network publics on Twitter: Networked framing, affect, and capture. Social Media + Society, 4 (1), 2056305118764437. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118764437

Smith, M. a, Rainie, L., Shneiderman, B., & Himelboim, I. (2014, February 20). Mapping Twitter topic networks: From polarized crowds to community clusters. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech.

https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2014/02/20/mapping-twitter-topic-networks-from-polarized-crowds-to-community-clusters/

Statista. (2024). Most popular social networks worldwide as of April 2024, by number of monthly active users. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

Strauß, H. (2017). Comparatively rich and reactionary: Germany between “Welcome Culture” and Re-established Racism. Critical Sociology, 43 (1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920516683643

Tomsic, E., & Looy, J. V. (2022). Exploration of opinions and news media reporting on the Russian-Ukrainian war in Flanders. KU Leuven.

Traub, J. (2022, March 21). The moral realism of Europe’s refugee hypocrisy. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/03/21/ukraine-refugees-europe-hyporcrisy-syria/

Tucker, J. A., Guess, A., Barbera, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A review of the scientific literature (SSRN Scholarly Paper 3144139). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3144139

Vilella, S., Lai, M., Paolotti, D., & Ruffo, G. (2020). Immigration as a divisive topic: Clusters and content diffusion in the Italian Twitter debate. Future Internet, 12 (10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi12100173

Walsh, J. P. (2023). Digital nativism: Twitter, migration discourse and the 2019 election. New Media & Society, 25 (10), 2618–2643. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211032980

Walsh, J. P., & Hill, D. (2023). Social media, migration and the platformization of moral panic: Evidence from Canada. Convergence, 29 (3), 690–712. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565221137002

Weber, M., Grunow, D., Chen, Y., & Eger, S. (2023). Social solidarity with Ukrainian and Syrian refugees in the Twitter discourse. A comparison between 2015 and 2022. European Societies, 26 (0), 346–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2023.2275604

Williams, H. T. P., McMurray, J. R., Kurz, T., & Hugo Lambert, F. (2015). Network analysis reveals open forums and echo chambers in social media discussions of climate change. Global Environmental Change, 32 , 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.03.006

Yi Huang, L. (2019, November 8). Who are the opinion leaders online? A case study of the immigration debate on Twitter in Sweden. Proceedings of The International Academic Conference on Research in Social Sciences. International Academic Conference on Research in Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.33422/iacrss.2019.11.632

Yoo, J. J. (2019). Opinion leaders on Twitter immigration issue networks: Combining agenda-setting effects and the two-step flow of information [The University of Texas at Austin]. https://doi.org/10.26153/tsw/5355

Young, S., Bourne, S., & Younane, S. (2007). Contemporary political communications: Audiences, politicians and the media in international research. Sociology Compass, 1 (1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00023.x

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the OPPORTUNITIES project, funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research & Innovation program under Grant Agreement No. 101004945, and by the HumMingBird project, under the same program under Grant Agreement No. 870661. The funding sources were not involved in the study’s design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation,

nor did they participate in the writing of this article. We are grateful to the journal editor and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and constructive feedback.

Supplementary Material

S1. Codebook for Attitude Classification

First, we classified the top retweets per community in the network to find the attitude of each community in accordance with the following coding scheme.

Table S1: Codebook for Labeling Attitudes

|

Code |

Examples |

|

1. Negative Tweets (Code: -1) Definition: Tweets that express explicit opposition, criticism, or negative sentiment toward refugees. We also classified tweets claiming most of the refugees were not from Ukraine as negative concerning 2022 for the community attitude classification. |

Economic Cost: “Refugees are getting free benefits while our citizens suffer.” Security Risk: “Allowing refugees is a security threat. We don’t know who these people are! #CloseTheBorders” Cultural Difference: “These refugees don’t share our values” Conspiracy Theories: “The government is using the refugee crisis to replace us with non-Germans. #WakeUp” Non-Ukrainians among Ukrainians: “Most of these so-called Ukrainian refugees are actually from the Middle East. #Scam” |

|

2. Neutral/News/Ambiguous Definition: A) Tweets that are neutral in tone, simply report news, or provide factual information without expressing a clear positive or negative sentiment toward refugees. B) Tweets whose meaning is ambiguous, hard to interpret or could be supported by both sides. Overall, these tweets do not indicate a clear stance and are often objective or ambiguous. |

News Reporting: “Thousands of refugees arrived in Munich today, marking the highest number this week. #RefugeeCrisis” Objective Information: “The EU has announced new measures to support Ukrainian refugees. #EURefugees” Statistics Sharing: “According to recent data, the number of refugees has increased by [number]% this year” Ambiguous: “EU Interior Ministers special meeting on refugees on September 14th. Apparently, it’s not urgent.” |

|

3. Positive Tweets (Code: 1) Definition: Tweets that express explicit support, solidarity, counter anti-refugee discourses, or positive sentiment toward refugees. |

Solidarity: “We must stand with refugees in their time of need. #WelcomeRefugees” Humanity/Victimhood: “These refugees have faced unimaginable hardships. Let’s show them compassion. #SupportRefugees” Countering Negative Narratives: “Refugees contribute positively to our society. Don’t believe the hate. #RefugeesWelcome” |

Note: The examples above are translated, paraphrased, and shortened.

S2. Attitude Classification Results

Next, we provide detailed information on the top ten communities identified by the Louvain algorithm and their assigned attitude labels (S1). “#” indicates the ranking of the community based on size; “Com” is the arbitrary community ID assigned by the community detection algorithm, included as identifier; “Size” represents the population of the community; “Anti,” “N/M,” and “Pro” display the distribution of anti-refugee, neutral/mixed, and pro-refugee messages within the analyzed retweets, respectively. “Average” refers to the average position calculated by assigning -1, 0, and 1 to the retweets. “Label” is the assigned label. Two coders classified the retweets based on their stance concerning the refugees; we report here the code from one of them. For more details, see the methods section.

Table S2a: Communities to Attitudes (2015, N1)

|

# |

Com |

Size |

Anti |

N/M |

Pro |

Avg. |

Label |

|

1 |

3 |

7,434 |

0 |

11 |

32 |

0.74 |

Pro |

|

2 |

64 |

6,807 |

2 |

21 |

20 |

0.42 |

N/M |

|

3 |

1 |

6,377 |

0 |

14 |

31 |

0.69 |

Pro |

|

4 |

0 |

5,948 |

0 |

6 |

41 |

0.87 |

Pro |

|

5 |

11 |

5,301 |

0 |

6 |