Innovating Democracy?

Analyzing the #WirVsVirus Hackathon

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a multitude of crises in contemporary societies, accelerating the adoption of digital technologies in business, culture, and politics. From video conferencing to tracing apps to modeling social behavior, in many ways, the almost complete transition of social communication to digitally mediated formats represents a clean break with the existing paradigm. In the field of (democratic) politics, public debate and political science research alike have focused on new control technologies, such as the various contact tracing and quarantine apps (Tretter, 2023; Zar & Elkin-Koren, 2023). Nonetheless, there have also been changes in the form of democratic politics and social self-organization. States have experimented with digital formats that should enhance their problem-solving capacities and boost innovation without excluding the citizenry from the process.

The growing importance of civic hackathons reflects this. Hackathons originated in the late-1990s open-source movement. Their basic principle can be summarized as “putting problems into code” (Ermoshina, 2018, p. 80). They often serve as a playground for tinkering and allow participants to socialize in a creative and inspiring atmosphere and, as an organizational format, enable the collaborative development of technological solutions to pre-defined problems. The format has been widely adopted by commercial actors as a means of fostering an agile working culture, with a public variant also emerging in the form of civic hackathons that explicitly aim to solve societal problems. Civic hackathons center the development and use of digital infrastructures for fostering the common good by and for civic actors. During the COVID-19 crisis, civic hackathons worldwide became a prominent tool for collaboration between citizens, bringing together notions of state digitalization, democratic participation, and social innovation.

Probably the most famous COVID-related civic hackathon is the #WirVsVirus hackathon that took place in Germany from March 20 to 22, 2020. The German federal government gave the hackathon its full support, labeling it “Der Hackathon der Bundesregierung” (The Hackathon of the Federal Government). In addition, the country’s then-Chancellor Angela Merkel sent a message of support and President Frank-Walter Steinmeier met with representatives of the initiating Civic Tech actors. After the hackathon attracted widespread media and political interest, more and more countries adopted the idea and organized their own hackathons, with the European Commission even launching a pan-European #EUvsVirus hackathon. In each case, civic hackathons were considered a means of responding quickly and comprehensively to the multiple challenges of the pandemic and engaging a wide range of citizens in the effort. Even after the crises subsided, civic hackathons maintained their appeal. They expanded in scope and support structures, as exemplified by #UpdateDeutschland, a second German government-sponsored hackathon held a year after #WirVsVirus.

In what follows, we closely consider the #WirVsVirus hackathon to analyze the democratic implications of civic hackathons as a political format. 1 We assume that it is possible to discern the general trends, risks, and opportunities of hackathons as a certain kind of democracy-focused social innovation by investigating this formative and keenly observed instance. The literature has mostly framed civic hackathons as a participatory format, with the main question always concerning the extent to which the citizenry is included (Johnson & Robinson, 2014; Ermoshina, 2018). However, civic hackathons are not only a way to directly engage but also a way to constitute political subjects. Furthermore, insofar as the institutionalization of civic hackathons as a political format reconfigures the relationship between the state and the citizenry, we must closely examine the kind of political subjectivity constituted here. To investigate this reconfiguration and broaden the scope of the research literature on hackathons, we discuss how societal descriptions of problems and options for action are produced, recognized, or rejected in and through the hackathon format.

Hackathons, we argue, have a representative or symbolic dimension. Like all forms of political or civic organization, they not only structure the actions of their participants but also constitute a distinctive way for the citizenry to perceive and address themselves. Therefore, we propose engaging with the theoretical toolbox of representative-theoretical analysis, especially the distinction between claim-making and claim-taking (Saward, 2006; cf. Disch et al., 2019). This allows us to focus on who can frame a problem and who decides how claims are handled. According to our analysis, the civic tech 2 initiatives that organized the hackathon especially successfully asserted claims to speak for the citizens and establish a new form of political participation. However, this political mode of participation had implications for the citizens’ claim-making and claim-taking capacity: Although the process generated general political claims, these were both (pre-)formed and systematically limited by the organizational design and technological infrastructure. Similarly, with regard to the recognition or rejection of representative claims (claim-taking), the focus on feasibility promoted a tendency towards an expertocratic decision-making structure. This had consequences for the diversity of recognized claims.

To develop this argument, we first contemplate the theorization of civic hackathons. We review previous research and perspectives that usually either define hackathons by their solutionist shortcomings or understand them as participatory panaceas. By contrast, our approach draws from modern democratic theory and focuses on the representational making and taking of claims. This is followed by the empirical investigation of #WirVsVirus, which sees us analyze the hackathon’s key phases and discuss how its technological mediation, procedural mode, and the distribution of agency structured the process. Next, we turn to the democratic implications of this structuring and examine the results within the larger context of the transformation of democracy. We conclude by formulating ideas concerning how civic hackathons can better comply with their democratic claims.

2 Theorizing Civic Hackathons

Given the growing popularity of the civic hackathon format, it is unsurprising that social science research has increasingly turned its attention to the phenomenon (Endrissat & Islam, 2022; Robinson & Johnson, 2016; Lodato & Di Salvo, 2016; Johnson & Robinson, 2014; Briscoe & Mulligan, 2014). Most of the literature begins analysis with the public perception that civic hackathons signal a willingness to engage in transparent and participatory governance and attempt to improve on the work of government itself (Schrock, 2019). 3 The literature can be roughly divided into two strands: a rather optimistic outlook that focuses on opening up public administration and a critical approach that highlights the exclusionary and depoliticizing effects of hackathons.

Current approaches concerning COVID-19–related civic hackathons mostly pertain to the positive camp, depicting the hackathon as an alternative to bureaucratic-administrative procedures because the practical orientation transmits the notion that institutionalized politics are insufficiently open to experimentation (Ermoshina, 2018). These papers focus on the hackathon’s open and self-selecting participatory structure and its problem-solving mode of action. Hackathons are thought to recover the potential of a vibrant and technologically savvy civil society, outperforming hierarchical structures of command and control, especially in situations with high uncertainty and a plethora of related problems and effects (Temiz, 2021). Accordingly, the literature on #WirVsVirus and related crisis hackathons most often interprets them as a form of collaborative crisis government within the context of open government and open social innovation (Haesler, 2020; Thiele & Pruin, 2021; Mair & Gegenhuber, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic is considered a wicked problem that requires an effort beyond classic crisis management (Bertello et al., 2021). This prompts perceptions of hackathons as a way to address this dynamic and highly contingent reality by strengthening societal communication and self-organization, enabling creativity and local problem detection and solving (Criado & Guevara-Gomez, 2020). According to this view, at best, they not only produce solutions to concrete problems but also change the relationship between citizens and governments. Beyond being subjects to be taken care of or data points to be measured, citizens are understood to have an active role in driving innovation (Haesler, 2020). 4

This rather optimistic view of the potential of civic hackathons is shared by the official research team for the #WirVsVirus hackathon. Their “Learning Report,” published a year after the original hackathon, measures the impact largely in terms of its open social innovation method (Mair et al., 2021). They conclude that beyond individual development opportunities and successful projects, the hackathon shifted the relationship between different actors: Institutions of the administrative state established new ties with citizens and, in the course of a rather sudden change of values, opened up to their innovative ideas (Gegenhuber et al., 2021). At a systemic level, open social innovation via civic hackathons (e.g., #WirVsVirus) could, therefore, prompt greater political participation, leading to advocacy for its position as a blueprint for other societal challenges.

The more critical strand of the literature argues that the participatory-inclusive promise of hackathons is deceptive, with civic hackathons representing an instance of technological solutionism. In this view, hackathons are by no means inclusive. On the contrary, they are replete with prerequisites: They require that participants have time, organizational and technological competencies, and resources. 5 Furthermore, they reduce complex problems to small-scale, pragmatic dilemmas and leave little room for broader reflection on the causes of the problem. Often it is the solution that determines what the problem actually was (Dickel, 2019, p. 104). According to this perspective, participants are pushed by the format into the role of “entrepreneurial citizenship,” which sees them feel (politically) engaged but unable to achieve solidarity or critical consciousness-raising (Irani, 2015, p. 801; Gomez & Thornam, 2016). By doing so, hackathons align with a general trend towards transforming resistant forms of political action into more cooperative patterns of action (see Thiel, 2017). They can be read as an “attempt at routinizing” hacking (Dickel, 2019, p. 96; Gregg, 2015) and as a breeding ground for start-ups where (open) social innovation functions as a way to combine the public good with profit orientation (Chesbrough & Di Minin, 2014). Consequently, hackathons can be understood as a depoliticization of collective action, further fostering a neoliberal “undoing the demos” in democratic politics (Brown, 2015; Perng et al., 2018).

What the participatory praise and solutionist critique perspectives share is that they interpret hackathons as mere participatory tools. Openness and effectiveness are their main yardsticks for ascertaining normative suitability, with both perspectives tending to presume that there is already a given political subject that can be either activated or silenced by the hackathon’s formal arrangement.

In what follows, we want to enhance this perspective by exploring how political subjectivity is formed in and through the process of the hackathon itself. As such, we adopt as our starting point the perspective of modern democratic theory, specifically, representation-theoretical analysis as formulated after the so-called representative turn (Näsström, 2011). 6 Approaches in this line of thinking reject an identification of democracy with participation in opposition to representation (Plotke, 2002). Instead, they highlight how civic participation is structurally embedded within the broader political process of political representation, that is, how political deliberation and judgment are structured and linked to processes of political decision-making (cf. Urbinati, 2014, p. 22). This perspective emphasizes how even far-reaching openness to participation may produce exclusions and hierarchies. To take this into account, the main focus of a representational analysis concerns how interactive relationships of representation are structured and how, performatively, a democratic subject is politically generated and meaningfully configured (Disch et al., 2019). Democratic representation is characterized by the fact that it offers a mode in which different ideas of political problem-solving are brought into competition with each other under the claim of serving the common good or public interest. These are discussed in public forums, whereby citizens can form political opinions that are then translated into decisions. Thus, public judgment and representative decision-making represent different but interrelated modes of democratic action (Urbinati, 2006) that are always complemented by the configurative and legitimacy-giving mode of symbolic representation (Breckman, 2012; Diehl, 2019). Iterative and interactive processes between representatives and citizens form opinions and translate them into decisions. At the same time, a collective political subject We is constituted and, through this performance, made intelligible and experienceable. 7

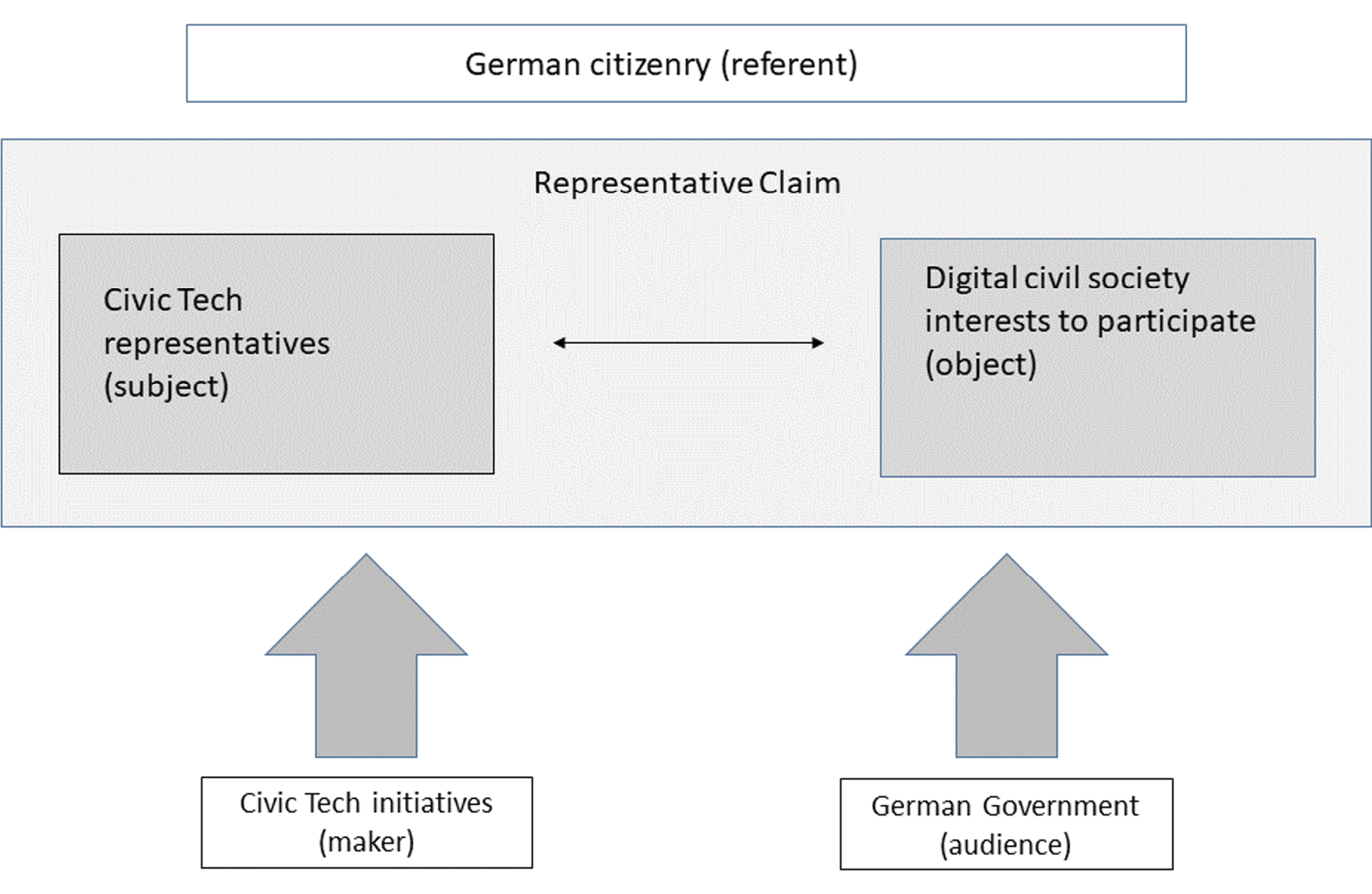

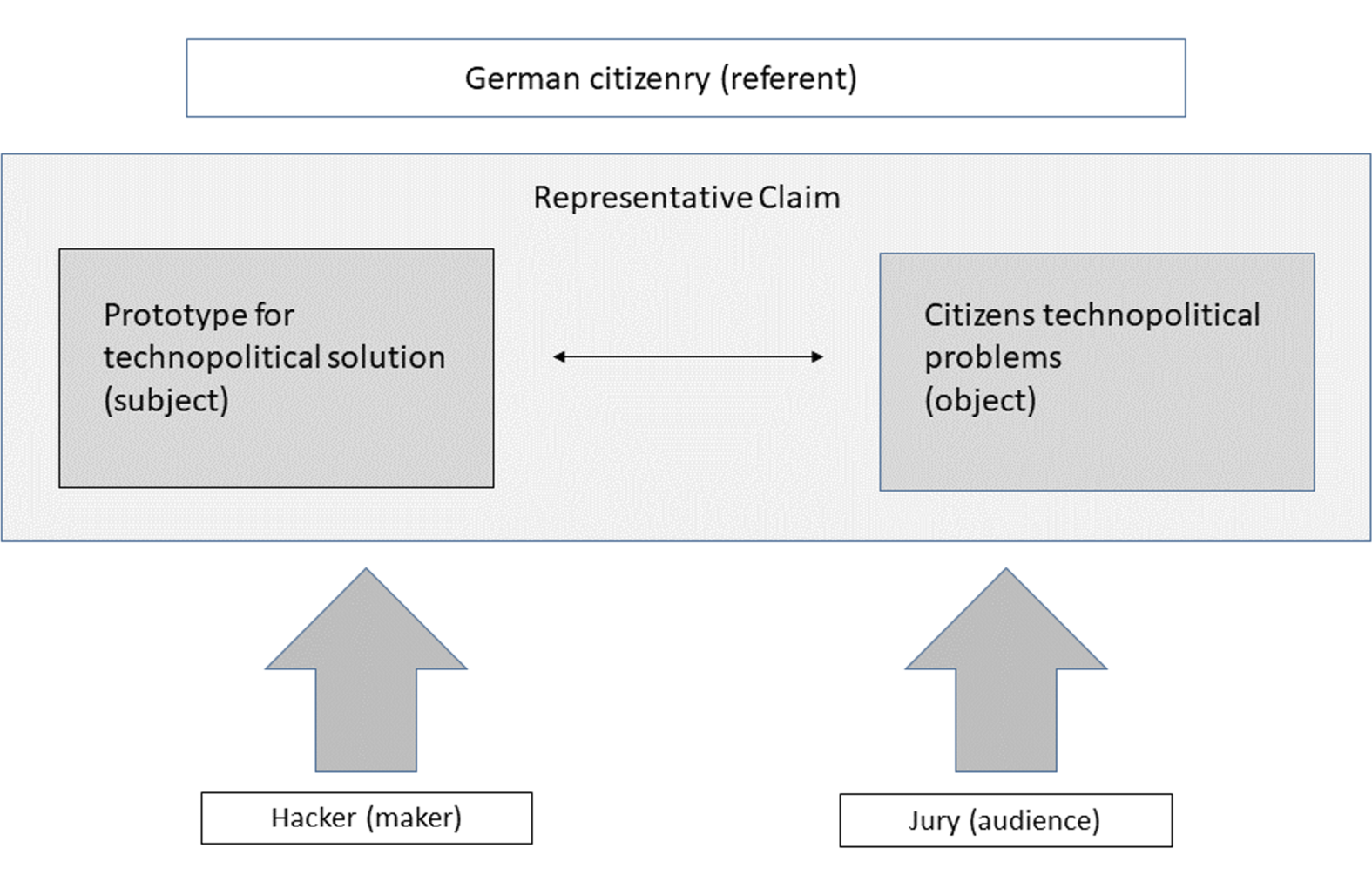

Michael Saward deserves credit for translating these theoretical considerations into the empirically operationalizable concept of the “representative claim.” Expressed in an abstract formula, representational processes are understood as the presentation and recognition of representative claims: “A maker of representations (M) puts forward a subject (S) which stands for an object (O) which is related to a referent (R) and is offered to an audience (A)” (Saward, 2006, p. 302). Using this abstracted view, it is possible to analyze how, in different contexts, political subjects are produced, concepts of order are constituted, and legitimacy is symbolically negotiated through representationally structured interactions in political debates.

By linking the assertion of representational claims (claim-making) and the formation of judgments about and the acceptance or rejection of claims (claim-taking) as two interlocked constituent aspects, citizens and representatives are brought into a common political relationship of interaction that constitutes political subjectivity.

When political representation is understood as an interactive, performative relationship that can also be exercised in various social arenas and contexts by entities such as social movements, trade unions, and media personalities, it is clear that civic hackathons can also be interpreted as representative procedures. In civic hackathons, particular problem diagnoses and proposals for action are brought forth to be validated and authorized as communal and general descriptions by means of a structured debate process. 8

To date, the literature on representative claims has primarily focused on discursively presented claims, underestimating the formative effect of media contexts and material expressions. However, within the hackathon, “arguments by technology” (Kelty, 2005) are articulated in both the production of technological prototypes and their material presentation in public space. The study of civic hackathons and the broader context of a form of civil society that is oriented toward and operates via technology make it necessary to reflect on the ways that technological infrastructures are important for the production of representative claims. Consideration of how representational claims are “enacted through work in and on material objects” (Marres & Lezaun, 2011, p. 496) aligns with an approach that decenters linguistic acts as the key to the political realm. 9

A representational analysis (as attempted here) improves on the participatory perspective offered by most other literature in at least two ways. First, it allows us to decipher the production of political claims to the common good, the symbolic component, and the importance of mediating institutions. A representation-theoretical analysis examines the conditions and constraints under which claims can actually be staged and what audience is enabled to perform the claim-taking. On the basis of this analysis, it is possible to determine the extent to which expectations of democratic participation are justified. Second, the approach moves beyond the rhetoric of more or less participation and normatively offers a vocabulary that encompasses the democratic value of raising, channeling, and configuring claims.

We now turn to the empirical analysis of the #WirVsVirus hackathon to examine how the hackathon format structures the making, evaluation, and acceptance or rejection of representative claims.

3 Methodology and Data

Our study of #WirVsVirus was conducted using an explorative-qualitative approach and a research design with staged sampling. As a first step, and to explore the field, we conducted an analysis of the extensive public written and video material. Of particular importance was the dynamic handbook made available to participants (#WirVsVirus, 2020a).

Based on document analysis, we developed a semi-structured interview schedule that included questions about the constellation of actors supporting the format, the processes of making, acknowledging, and rejecting claims to representation, the role of digital media, and the institutionalization of the format. Then, we selected seven interviewees who had played a formative role in shaping the hackathon in various capacities: two people who were responsible for the civic tech initiatives responsible for organizing the event (Prototype Fund/ProjectTogether), two people who were responsible for the hackathon at the Federal Chancellery (double interview), one juror and two people involved in hackathon projects (Ich bin kein Virus/Corona vor Ort). In addition to these expert interviews, we had access to a survey completed by 1,022 participants and mentors, a survey conducted by the civic tech initiatives that organized the hackathon. 10

3.1 #WirVsVirus: Four Phases

The #WirVsVirus hackathon can be conceptually divided into four phases: the initiation phase (1), the problem-definition phase (2), the problem-solving phase (3), and the stabilization phase following the actual hackathon (4).

Initiation

The seed for the #WirVsVirus hackathon can be identified in a Twitter conversation on March 15, 2020. That conversation brought together several representatives of the eight organizations from the German-speaking civic tech community that would later officially initiate the hackathon. The German government was also already represented by the head of the Digital Policy Unit in the Federal Chancellery. The subject of the conversation was the successful implementation of the online hackathon “Hack the Crisis” in Estonia (March 13 – 15), and the discussion concerned implementing a similar format in Germany. The organizers assumed that there was “a will among the population to get actively involved” but that this would require “a new format for social participation that allows civil society to contribute to solving challenges in a coordinated and effective way” and to combine its “creative potential” (#WirVsVirus, 2020b, own translation and emphasis). #WirVsVirus was intended to unite civil society and politics and enable political action regardless of pandemic-related restrictions on socializing. On the part of the government – which at this point primarily meant the Federal Chancellery – it was already clear in the initial phase that sustainability, in the sense of the capacity to implement “real” solutions beyond the event, was the conditio sine qua non for its involvement (Interview with the Federal Chancellery). Only three days after that first conversation, both the name #WirVsVirus and the legitimacy-lending tagline of the hackathon (“The Hackathon of the Federal Government”) were decided upon and publicly communicated.

Problem Definition

On Thursday, March 18, the call for participation in the hackathon was widely distributed on social media and beyond. This call asked participants to submit problems that could be understood as “challenges” to be overcome during the COVID-19 crisis. The target group was kept open, with the ambiguous term “problem solvers” employed, but it was clearly action-oriented, inviting anyone who had “the desire and time and [...] internet access” to participate (#WirVsVirus, 2020c, own translation). Beyond the public, members of state bodies were also explicitly addressed.

Despite the tight time frame, more than 2,000 submissions were generated, including 200 problem descriptions submitted by federal ministries (#WirVsVirus, 2020a). These were assessed by the organizers according to factors including impact, feasibility, and quality. A total of 809 submissions were considered for inclusion in the process and divided into a total of 48 thematic challenges. The spectrum ranged from infection control and contact tracing to combating the social consequences of the pandemic, such as isolation and loneliness (for a presentation and discussion of several projects resulting from the hackathon, see Mair et al., 2021).

Members of the public who registered to participate in the hackathon received an overview of the 48 challenges and access to the official workspace on Slack, the hackathon’s central communication platform. Participants could assign themselves to the channels created for the challenges and form teams. This team-building process was supported by mentors, who offered orientation and technological assistance. 11

Problem Solving

The main phase of the hackathon involved the development, presentation, and evaluation of prototypes. Teams were encouraged to work on their prototypes until Sunday night and then present them in the form of a two-minute video. A total of around 1,500 proposals were received via Devpost and YouTube, which were reviewed the following week.

Although the hackathon’s organizers initially planned a public vote, this idea was withdrawn after some participants raised concerns. They noted that such a vote would be distorted by the high media profile of certain individual participants. Instead, a review process was established that saw around 700 people (mentors, experts, and employees from federal ministries) initially appointed by the organizers and asked to evaluate the prototypes according to the “ten-eyes principle” using the criteria “social added value,” “innovation,” “feasibility and scalability,” “idea stage (progress),” and “understandability” (#WirVsVirus, 2020a, p. 5). This process led to the identification of 197 favorable solutions that were subsequently divided into five thematic groups (medical care/diagnosis and dissemination/administration, information and data/economy, work and education/welfare) and presented to a 48-member jury.12 The jury did not function as an interactive body. Instead, jury members were each asked to identify promising solutions and communicate them back to the organizers (Interview with Juror). On this basis, twenty “jury-awarded projects” were selected.

Stabilization

The hackathon’s implementation phase began when the winning projects were selected and ended with the official closing event on October 1, 2020, for which numerous funding partners were solicited by the coordinating bodies in the Federal Chancellery and digital civil society. The program comprised three funding lines. First, the Solution Enabler program supported a total of 130 initiatives, 80 % of which were created within the framework of the hackathon. Initiatives were supported with their concepts, human resources, and (partly) their financing. However, with the exception of the winning projects, repeated application was required.

Meanwhile, the Solution Builder program established “fast track” for ten of these projects, and the Matching Fund program featured a crowdfunding campaign including a percentage grant. Until the end of June, community management also continued on Slack, which served as a moderated discussion forum and a place to search for experts. This offered non-funded projects the opportunity to continue working on their idea. Beyond the work on implementing individual projects, this final phase was characterized by attempts to stabilize the format, which were also symbolically legitimated. Hence, the highest elected representatives of the Federal Republic of Germany – the Federal President and the Federal Chancellor – actively sought dialogue and, in public messages and meetings, emphasized not only the importance of the hackathon but also of digital civil society engagement more generally.

3.2 #WirVsVirus: Structures and Dynamics

Building on the foregoing overview of the timeline of the hackathon, this section analyzes the structures and dynamics of #WirVsVirus. This involves first determining the central representational processes in each of the four phases before interrogating the structuring mechanisms in operation. In each of the four phases, the representational processes can be differentiated into claim-making and claim-taking.

Representational Processes in the Four Phases

The initiation phase is the constituent phase of the hackathon. It sees the format itself established and specified, with the civic tech initiatives acting as claim makers and established politics in the form of the federal government representing the central audience that had to decide on claim-taking. The civic tech initiatives (makers) established themselves (subjects) as representatives of the German civil society who wanted to participate in the political solution to the pandemic (object). The German government approved the claim when the Federal Chancellery decided to engage with the initiatives (see Figure 1). As repeatedly emphasized in the interviews, the close contact and the existing networks between the civic tech ecosystem and political actors were decisive in realizing the hackathon. The initiating civic tech actors saw their task as “trust brokering,” which meant mediating between civil society and the political sphere. They were able to “approach certain people that such an initiative from civil society normally cannot approach” (Interview with ProjectTogether 13 ). Because of the trust in the actors, the Federal Chancellery was willing to push the process on the political side and (especially) to encourage the federal ministries to cooperate: “It was a fortunate combination of people we knew and who we knew were very, very reliable, people who have a good network and we were able to offer our patronage” (Interview Federal Chancellery).

Figure 1: Claim-Making in the Initiation and Stabilization Phase

Notably, the group of initiating actors was largely recruited from the Berlin civic tech community. Their perspectives and experiences dominate the German discourse, but it must be assumed that their habits and content differ substantially from other civil society actors. This close connection also means that the model cannot be directly transferred to other initiatives and contexts. Informal contacts and the associated trust were central factors in the initial phase, which underscores the contingency of the hackathon as a political structure.

In the problem-definition and problem-solving phases, not only the actors but also the structure of representation changes (Figure 2). During the problem-definition phase, the claim-making process was openly constructed and took place directly from within society, with the recognition of the problem definitions (i.e., the claim-taking) and decisions about their presentation a task for organizers. The challenge’s structuring in 48 clusters configured the pandemic as a problem complex that confronted the crisis community and activated it to collaborate.

Figure 2: Claim-Making in the Problem-Definition and Problem-Solving Phase

During the problem-solving phase of the hackathon, claims were structured according to the prototypes or videos presented by the projects. Participants directly expressed their views of the problem and proposals concerning how to respond to the challenges of the crisis in this material-visual way. At the same time, they asserted the feasibility and effectiveness of their proposals. The audience in this phase was twofold. On the one hand, the general public could follow the entire hackathon in a low-threshold way. This is what Saward coins the “intended audience” (cf. Saward, 2010, p. 49). On the other hand, having discarded the idea of the public vote, the expert public comprising decision-makers decided in a ranking mode whether the proposed solutions were worthy of recognition. This is Saward’s “actual audience.” Although the constitution of claims – that is, the development of prototypes – was characterized by an interactive and creative dynamic, the judgment of each claim’s deservingness was characterized by a rationalist and hierarchical mode based on objective criteria and expert knowledge. The expert jury actively perceived itself as a filter that contemplated the context and focus of the process: “There are more delicate questions or some approaches are more delicate than others, and for such a broadly effective hackathon, where the Federal Chancellery is involved, one perhaps doesn’t try to put the most controversial things in the spotlight” (Interview with Juror).

The final, prolonged phase of stabilization returns to the higher level of negotiation between civil society and the state. Here, claim-making is again undertaken by the organizing civic tech actors. They used the successful implementation of the hackathon as an opportunity to strengthen their claim to the organizational capacity of achieving broad public participation, a claim made in the initiation phase. In particular, the organization ProjectTogether became the hinge, as the following remarks succinctly demonstrate:

It was clear from the beginning that we think it should not only be a hackathon, but it should be more. We also considered from the beginning what should happen after the hackathon. That is, we wrote our concept for the follow-up implementation program – the Solution Enabler program – during the hackathon. (Interview ProjectTogether)

The ProjectTogether network coordinated the implementation processes and initiated further activities, such as the 2022 follow-up hackathon #UpdateDeutschland. It also organized communication mechanisms, such as the closing events. This can be considered a form of state recognition for a new constellation of civil societal self-organization that accepts the need to shape a digitalized society in changing ways and therefore fosters broader opportunities for civil society to organize and exert influence. These opportunities involve not only the transfer of organizational responsibility but also the possibility of establishing substantive priorities. For example, the focus on the principle of “public money–public code,” which refers to a preference for open-source projects, represents a central concern for most civic tech actors (Interview Prototype Fund). The final phase also saw a striking semantic shift around the spirit of the hackathon, with the event now overwhelmingly described in terms of open-social innovation, a term advocated by more professionalized civil society organizations and readily accepted by the public administration, to the extent that the term became an important reference point in the coalition agreement of the next German government. Meanwhile, the more political nomenclature characteristic of the initial phase, such as citizen participation and solidarity, faded.

It is now possible to step back to reflect on how the processes of representation were structured and how the boundaries of inclusivity and articulateness were created and follow-up opportunities shaped. There were claims of democratic mobilization, which at first glance seems to have been entirely successful. The #WirVsVirus hackathon was said to have brought together those “who can code and those who don’t even know what that actually means” to become “a positive part of civil society” (Bär, 2020, 33.57). However, these claims must now at least be qualified.14 In this context, it makes sense to closely consider the structuring effects of the technology, the procedural rules, and the distributed agency of the actors that shaped the hackathon’s power dynamics.

Technical Mediation

Digital technology was a prerequisite for not only #WirVsVirus itself but also for the prototypes developed. However, technical infrastructures are never neutral mediators, instead creating a space of possibility for communication and coordination (Hofmann, 2019).15

Two examples illustrate how such infrastructures operate. First, there is Slack, the communication platform chosen for the hackathon. A Slack workspace is essentially structured by division into channels, with users exchanging information on the channels they belong to. Although the organizers emphasized the simplification effect of participants assigning themselves to teams and topics, exchange between channels was largely minimized (Interview Ich bin kein Virus/Interview Corona vor Ort). Distinct from a physical hackathon, there were few opportunities for people to casually encounter each other and no chance to look over figurative shoulders at the problem definitions and ideas of other groups. Overarching channels only existed to answer questions, undertake general organization, make announcements, and facilitate communication between specific groups, such as mentors. This meant that a discussion of the general aspects of the pandemic’s social challenges did not build momentum and was not even intended. Larger community building only took place in the context of framing events, such as the presentation of projects on YouTube or the closing event. However, these mainly functioned unidirectionally and created a sense of belonging by thanking and addressing participants rather than enabling communicative discussion.

Second, the presentation of the solutions themselves demonstrates the structuring effect of technology. The prototype and the video to be uploaded can be read as a materialized argument: an “argument-by-technology” (Kelty, 2005, p. 187). These are based on participants’ perceptions of the problem and represent the idea of a feasible solution (see Dickel, 2019, p. 104). Thus, the prototypical claim has, at least in principle, a differentiated repertoire of arguments that is perceived on different levels and invites debate. At the same time, its materiality and technicality shape and limit what can be argued convincingly. In combination with the short time scale and the logic of presentability, this results in a focus on making small adjustments with (supposedly) great effects.

Procedural Mode

The mode in which the hackathon was conducted represents the second dimension through which representational processes were structured in the long term. Although practical organization was mainly driven by the organizing civic tech initiatives, the influence of the Federal Chancellery can be observed in the fact that the hackathon was geared towards success in the sense of feasibility and the development of flagship projects:

We were always very keen to find these examples of success and then also to promote projects that have great potential in a much more targeted way. In other words, not to get lost in the masses but to focus through the implementation program on those projects to which we also say, yes, this could lead to a good result. (Interview Federal Chancellery)

Although the civic tech ecosystem often emphasizes that the value of hackathons concerns not primarily the projects themselves but rather the networks and the exchange of ideas made possible by this playful, experimental method (Code for Germany, 2020). The focus in the political sphere was on legitimation via successful and innovative projects. Overall, in the case of #WirVsVirus, a competitive, solution-oriented structure prevailed that aimed at comparability and engendered time and competitive pressures: “At some point, we summarized everything in terms of competitiveness because we said that if a jury looks at it and wants to tick the boxes, we can just take the structure that is given to us in unchanged form and write something about each aspect” (Interview Corona vor Ort).

As in the case of technical mediation, the procedural mode also complicated reflection loops and exchange between projects. As in the case of other hackathons, the proponents sought to frame this as a feature rather than a bug, arguing that the “manufactured urgency” would act as a driver of creativity (Irani, 2015, p. 818). However, the command to “get shit done” – in a document on the hackathon referenced in the FAQs should be viewed critically, at least with regard to the democratic potential of the process. Specifically, the imperative to act fast ultimately reintroduced the asymmetries of experience and epistemic imbalances that the hackathon’s organizers had previously sought to reduce via inclusion mechanisms, such as the mentor program.

Furthermore, the format of the #WirVsVirus hackathon procedurally separated problem definition and problem-solving. Although politics normally sees claims for representation – whether they concern issues or constituencies – already linked to proposed solutions at the moment of articulation (e.g., “I want to represent constituency X with its high unemployment [problem definition], because my plan to promote tourism will create jobs [solution description]”), #WirVsVirus enabled challenges to be submitted without a proposed solution, with solution-focused teams then constituted via the challenges. This division is consistent with the competitive, solution-oriented idea of politics that the format calls for. It presumes that problems can be objectively identified and that, in attempting to solve them, the social experience from which the problem definition results plays only a subordinate role.

Distribution of Agency

Consideration of how the resources and positioning of actors created possibilities for structuring makes clear that claim-making and claim-taking should be evaluated differently. In terms of claim-making, the hackathon was characterized by relative openness. Both the submission of problem definitions and the participation in the development of solutions were avenues available to all interested members of the public, deliberately conceived as low-threshold activities. In terms of claim-taking, the format was not very dialogue-oriented, and the result was strongly asymmetrical. Here, civil society organizers and institutionalized political actors had a clear advantage because they configured the problem definitions, decided on criteria, selection mechanisms, and jury members, and ultimately also controlled society’s perception of the problem through their communication strategy.

It becomes very apparent how this excludes the citizenry from the hackathon. Although projects were made directly and transparently accessible to a diffuse but potentially unlimited public, the decisions concerning how worthy they were of recognition were made by an audience of experts. Thus, the citizenry remained in the role of a symbolically invoked legitimizing authority that was spoken for but not spoken with.16 In other words, citizens remained solely in the role of the referent (cf. Saward, 2010, p. 79).

Just how problematic this is can be illustrated by how organizers responded to criticisms from the Ich bin kein Virus project. That project’s team participated in the hackathon with a proposal for a platform to make COVID-specific experiences of racism visible and discuss them, but the proposal was abandoned after the first selection stage. The project’s representatives criticized the evaluation practices, arguing that neither the criteria employed nor the composition of the committees was sufficiently diverse or allowed for adequate consideration of social problems (Interview Ich bin kein Virus; Stuetz & Kure-Wu, 2020). However, the internal mechanisms available to voice this criticism and achieve thematic relevance did not generate any response. It was only when the project used the extremely popular Twitter account of the Peng! collective to criticize the #WirVsVirus organization that a discussion about the insensitivity to issues of diversity and racism was initiated. This resulted in the organizing civic tech initiatives making a statement indicating that they would seek to ensure more diversity-sensitive committee selection in the future (#WirVsVirus, 2020d), an intention also noted in the final report as a recommendation for action for future formats (#WirVsVirus, 2021). However, a mechanism for communicating conflicting positions and the possibility of criticism remains lacking.

4 Conclusion: Reflecting on a Democratic Prototype

We believe this can be a blueprint for how governments could address pressing challenges bottom up and collaboratively with civil society.

#WirVsVirus, 2020a, p. 11

In many ways, the #WirVsVirus hackathon can be interpreted as a prototype itself. It represents an attempt to demonstrate the possibility and usefulness of involving citizens in political processes by experimentally combining existing ideas and novel collaborations between different actors, even under conditions of substantial time pressure. As a prototype – especially one evaluated as a successful experiment by the organizing bodies – the #WirVsVirus hackathon itself will probably generate new path dependencies. Because it was used as a model for the design of interactions between citizens and political and administrative institutions, it enters the political imaginary of democratic politics under a regime of innovation and thus serves as an organizational resource in the future.

If we understand digital technologies as a medium of democratic self-governance in and through which social coexistence reconfigures itself, the political design of the formats and processes is itself of interest in democratic terms. Therefore, our analysis has attempted to reconstruct and take seriously the implicit claim of hackathons to facilitate participation and the attainment of the common good as a participatory format for civil society. Using the lens of democratic theory, we have made the performative logic of hackathons explicit and discussed their democratic suitability for advancing proposals to shape society. Although this normative claim is not the only metric available – an alternative might be the output in terms of, for instance, the quality of the projects delivered – it is an important one. With regard to Saward’s theory of democratic representation, we have distinguished between claim-making and claim-taking in relation to different phases and actors in order to identify structuring factors in the representation processes. Saward’s theory has provided us with a yardstick that enables the establishment of an explicit link between empirical observations and normative judgments. Employing the theory allows us to assess the extent to which the representative claims made by the hackathon can be transformed into a procedure that preserves substantial representation and plurality.

The initiation phase saw the #WirVsVirus hackathon represent a successful case of claim-making by civic tech initiatives vis-à-vis the administrative state. The claim by these civic tech activists that the hackathon as a political format could mobilize a broad spectrum of active citizens and produce innovative, implementable projects was eagerly adopted by the German government and supplemented with the highly symbolic charge of labeling #WirVsVirus the hackathon of the federal government. Consequently, we can observe the growth and consolidation of connections between politics and civil society, at least among those actors with a connection to Berlin’s civic tech community. Thus, the technologically oriented part of civil society and the specific modus operandi of the hackathon moved closer to institutionalized politics. With reference to the discussion about the transformation of democracy, a reconfiguration of the relationship between political-administrative actors and members of the public can be observed. One example is the Sovereign Tech Fund, which was established in 2022 to support the development, improvement, and maintenance of open digital infrastructures. The fund can be directly linked to actors and structures from the hackathon and presents itself as another instance of a change in the cultural relations between politics and civil society. However, it is also possible to recognize in this shift a takeover of the civic tech culture by the political establishment, a takeover of the kind already observed in other areas of civil society engagement. This appropriation often legitimizes political power by referencing openness and innovation, and it must be debated on a case-by-case basis whether those formats and collaborations activate the citizenry in a sensibly democratic way or push a neoliberal restructuring under the guise of civil society participation. This is particularly visible in the concept of open social innovation (cf. Rulf et al., 2021), which measures modernization primarily in terms of economic potential and marketization and advocates for solutionism rather than the political involvement of citizens (cf. Brown, 2015).17

Therefore, our overall assessment of the democratic potential of civic hackathons is skeptical, especially because opportunities for participation can never be equated with democratization in a straightforward way, as already demonstrated by the existing literature on hackathons and open government. Our analysis of the interactive structure of representative claim-making and taking in the hackathon phase shows that although the hackathon offers an open, self-selective structure for claim-making, the technical mediation, the procedures, and the distribution of agency create characteristic weaknesses, such as the reduction of possibilities for reflexive judgments and the relative compartmentalization of the experience of acting in concert. Such trade-offs should not be readily justified by the productivity gains of high pressure or the stated goodwill of the organizers. Democratic politics needs reflexive and collective interaction and structures that afford those interactions should be strengthened and upheld. With regard to claim-making, the focus should be on not only activating the citizenry as broadly as possible but also fostering exchange between projects and the possibility of discussing problems beyond the project level and at the required level of detail. The special feature of the hackathon – promoting intensive problem-solving by deliberately setting limits – need not be abandoned. This effect, which also centers on problem awareness, could be created by making the formulation of challenges more interactive or iterative or by less exclusively centering the implementation of the hackathon on “winning” projects. In this way, opportunities could be created to formulate solutions in a new and different way in order to generate more potential for surprise.

There is an even bigger need with regard to claim-taking. From the perspective of democratic theory, the multi-level jury structure ultimately implemented by the organizers is one-sided and structured to favor monological communication. Organizers are aware of the weakness, which was raised by all interviewees. Appointing a more diverse jury, as was specifically demanded, promised, and already implemented in the context of the Solution Enabler program, is a necessary step but not a sufficient one. The already envisaged public voting procedure would not be a democratic substitute per se, but it could serve as a preliminary stage leading to the jury procedure, thus generating more attention for the claims. From the perspective of democratic theory, it would be much more promising to move away from appointing the selection committee according to an expertocratic logic and to at least complement it with a kind of citizens’ council that reflects the diversity of the general public.18 In addition to developing the selection process in this manner, it is also critical to strengthen the internal contestation mechanisms, including their formalization.

Broadly speaking, the hackathon format certainly has democratic potential. However, to realize this potential, it is imperative to move away from thinking about the hackathon––and the field of open social innovation in general––using the logic of marketization and instead see it as a platform for politically shaping the democratic community. In this respect, #WirVsVirus has set a development in motion. However, as always in the context of democracy, it will continue to depend on the iteration more than the prototype.

5 References

#WirVsVirus. (2020a). Hackathon handbook. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://docs.google.com/document/d/1MZD5xhYcqsLHmoojv

WiymdTU7bxBSp1bVSpPox-OE6E/edit.

#WirVsVirus. (2020b). #WirVsVirus Startseite. Retrieved August 16, 2021, from https://WirVsVirus.org/.

#WirVsVirus. (2020c). Gemeinsame Pressemitteilung der Initiatoren des #WirVsVirus Hackathon der Bundesregierung vom 18. März 2020.

Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://initiatived21.de/gemeinsame-

pressemitteilung-der-initiatoren-des-wirvsvirus-hackathons/.

#WirVsVirus. (2020d). Stellungnahme zur Kritik an mangelnder Diversität. Retrieved April, 1, 2022 from https://docs.google.com/document/d/16j5x-pokWXrve4qjzRry3fMz7O3wS8xEEDwCF-73Mco/edit.

#WirVsVirus. (2021). #WirVsVirus Abschlussbericht. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://wirvsvirus.org/abschlussbericht/.

Alexander, J. C. (2011). The performance of politics: Obama’s victory and the democratic struggle for power. Oxford University Press.

Asenbaum, H. (2021). (De)futuring democracy: Labs, playgrounds,

and ateliers as democratic innovations. Futures, 134.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2021.102836

Baack, S. (2018). Practically engaged: The entanglements between data

journalism and civic tech. Digital Journalism, 6(6), 673 – 692.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1375382

Bär, D. (2020). 15 Uhr Pressekonferenz - #WirVsVirus Hackathon [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KOIymYis0l4.

Berg, S., & Staemmler, S. (2021, May 13). Update Deutschland: Zivilgesellschaft im Wettbewerbsformat. Netzpolitik. https://netzpolitik.org/2021/updatedeutschland-zivilgesellschaft-im-wettbewerbsformat/.

Berg, S., Clute-Simon, V., Freudl, RL., Rakowski, N., & Thiel, T. (2021). Civic Hackathons und der Formwandel der Demokratie [Civic hackathons and the transformation of democracy]. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 62(4), 621 – 642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11615-021-00341-y

Bertello, A., Bogers, M. L. A. M., & De Bernardi, P. (2022). Open innovation in the face of the COVID-19 grand challenge: Insights from the Pan-

European hackathon ‘EUvsVirus.’ R&D Management, 52(2), 178 – 192. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12456

Breckman, W. (2012). Lefort and the Symbolic Dimension. Constellations, 19(1), 30 – 36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8675.2011.00663.x

Briscoe, G., & Mulligan, C. (2014). Digital innovation: The hackathon phenomenon (Creativeworks London Working Paper No. 6:13).

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8675.2011.00663.x

Brown, W. (2015). Undoing the demos. Neoliberalism’s stealth revolution. Zone Books.

Chesbrough, H.W., & Di Minin, A. (2014). Open social innovation. In H.W. Chesbrough, W. Vanhaverbeke & J. West (Eds.), New frontiers in open innovation, (pp. 169 – 188). Oxford University Press.

Code for Germany. (2020, October 10). How to hackathon. Wann und wie Hackathons kommunalen Verwaltungen helfen können.

https://codefor.de/blog/hackathon-leitfaden/.

Criado, J. I., & Guevara-Gómez, A. (2021). Public sector, open innovation, and collaborative governance in lockdown times. A research of Spanish cases during the COVID-19 crisis. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 15(4), 612 – 626.

https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-08-2020-0242

Dickel, S. (2019). Prototyping society - Zur vorauseilenden Technologisierung der Zukunft. transcript Verlag.

Diehl, P. (2018). Die 5-Sterne-Bewegung als Laboratorium neuer Tendenzen und ihre widersprüchlichen Repräsentationsbeziehungen. In W. Thaa & C. Volk (Eds.), Formwandel der Demokratie, (pp. 127 – 154). Nomos.

Diehl, P. (2019). Temporality and the political imaginary in the dynamics of political representation. Social Epistemology, 33(5), 410 – 421.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2019.1652865

Disch, L., van de Sande, M., & Urbinati, N. (Eds.). (2019). The constructivist turn in political representation. Edinburgh University Press.

Elstub, S., & Escobar, O. (2019). Defining and typologising democratic innovations. In S. Elstub & O. Escobar (Eds.), Handbook of democratic innovation and governance (pp. 11 – 31). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Endrissat, N., & Islam, G. (2022). Hackathons as affective circuits: Technology, organizationality and affect. Organization Studies, 43(7), 1019 – 1047. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406211053206

Ermoshina, K. (2018). Civic hacking. Redefining hackers and civic participation. TECNOSCIENZA: Italian Journal of Science & Technology Studies, 9(1), 81 – 104.

Gegenhuber, T., Mair, J., Lührsen, R., & Thäter L. (2021, March 10). Strengthening open social innovation in germany lessons from #WirvsVirus. https://hertieschool-f4e6.kxcdn.com/fileadmin/2_Research/5_Policy_Briefs/OSI_Policy_Brief_2021_EN.pdf.

Geißel, B. (2012). Impacts of democratic innovations in Europe: findings and desiderata. In K. Newton & B. Geißel (Eds.), Evaluating democratic innovations (pp. 173 – 193). Routledge.

Gómez-Cruz, E., & Thornham, H. (2016). Staging the hack(athon), imagining innovation: An ethnographic approach (Working Papers of the Communities & Culture Network 8). https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/114827/

Gregg, M. (2015). Hack for good: Speculative labour, app development and the burden of austerity. The Fibreculture Journal, 25.

https://doi.org/10.15307/fcj.25.186.2015

Gryszkiewicz, L., Lykourentzou I., & Toivonen, T. (2017). Innovation labs: Leveraging openness for radical innovation? Journal of Innovation Management, 4(4), 68 – 97. https://doi.org/10.24840/2183-0606_004.004_0006

Guasti, P. & Geissel, B. (2021) Claims of representation: Between representation and democratic innovations. Frontiers in Political Science 3(591544), 1 – 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.591544

Haesler, S., Schmid, S., & Reuter, C. (2020). Crisis volunteering nerds: Three months after COVID-19 hackathon #WirVsVirus. 22nd International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services (pp. 1 – 5). https://doi.org/10.1145/3406324.3424584

Happonen, A., Tikka, M., & Usmani, U. (2021, December 14). A systematic review for organizing hackathons and code camps in Covid-19 like times: Literature in demand to understand online hackathons and event result continuation [Paper presentation]. International Conference on Data and Software Engineering (ICoDSE), Bandung, Indonesia.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICoDSE53690.2021.9648459

Hofmann, J. (2019). Mediated democracy – Linking digital technology to political agency. Internet Policy Review, 8(2). https://doi.org/10/ggnsb8

Hope, A., D’Ignazio, C., Hoy, J., Michelson, R., Roberts J., Krontiris, K., & Zuckerman, E. (2019). Hackathons as participatory design: Iterating feminist utopias. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1 – 14). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300291

Irani, L. (2015). Hackathons and the making of entrepreneurial citizenship. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 40(5), 799 – 824.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915578486

Johnson, P., & Robinson, P. (2014). Civic hackathons: Innovation, procurement, or civic engagement? Review of Policy Research, 31(4), 349 – 357. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12074

Jungherr, A., Rivero, G., & Gayo-Avello, D. (2020). Retooling politics: How digital media are shaping democracy. Cambridge University Press.

Keane, J. (2018). Power and humility: The future of monitory democracy. Cambridge University Press.

Kelty, C. (2005). Geeks, social imaginaries, and recursive publics. Cultural Anthropology, 20(2), 185 – 214. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.2005.20.2.185

Kimbell, L., & Bailey, J. (2017). Prototyping and the new spirit of policy-making. CoDesign, 13(3), 214 – 26.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1355003

Lodato, T. J., & DiSalvo C. (2016). Issue-oriented hackathons as material participation. New Media & Society, 18(4), 539 – 557.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816629467

Lukensmeyer C.J. (2017). Civic tech and public policy decision making. Political Science & Politics, 50(3), 764 – 771.

Mair, J., Gegenhuber, T., Thäter, L., & Lührsen R. (2021). Open social innovation: Gemeinsam Lernen aus #WirvsVirus (Working Paper: Learning Report). Hertie School. https://doi.org/10.48462/opus4-3782

Mair, J., & Gegenhuber, T. (2021). Open social innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 19(4), 26 – 33. https://doi.org/10.48558/Q78Z-F094

Marres, N., & Lezaun, J. (2011). Materials and devices of the public:

An introduction. Economy and Society, 40(4), 489 – 509.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2011.602293

Mazzucato, M. (2013). The entrepreneurial state: Debunking public vs.

private sector myths. Anthem Press.

Menger, M.-E. (2020). “WirVsVirus” – Erfahrungen beim Hackathon.

Information - Wissenschaft & Praxis, 71(4), 236 – 238.

https://doi.org/10.1515/iwp-2020-2097

Murphy, P. D. (2021). Speaking for the youth, speaking for the planet:

Greta Thunberg and the representational politics of eco-celebrity.

Popular Communication, 19(3), 193 – 206.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2021.1913493

Näsström, S. (2011). Where is the representative turn going?

European Journal of Political Theory, 10(4), 501 – 510.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1474885111417783

Patel, M., Sotsky, J., Gourley, S., & Houghton, D. (2013). The emergence of civic tech: Investments in a growing field. Knight Foundation

Perng, SY., Kitchin, R., & Mac Donncha, D. (2018). Hackathons, entrepreneurial life and the making of smart cities. Geoforum, 97, 189 – 197.

Plotke, D. (1997). Representation is democracy. Constellations, 4(1), 19 – 34. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.00033

Robinson, P. J., & Johnson, P. A. (2016). Civic hackathons: New terrain for local government-citizen interaction? Urban Planning, 1(2), 65 – 74. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v1i2.627

Rosanvallon, P. (2008). Counter-democracy: Politics in an age of distrust. Cambridge University Press.

Saward, M. (2006). The representative claim. Contemporary Political Theory, 5(3), 297 – 318. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.cpt.9300234

Saward, M. (2010) The representative claim. Oxford University Press.

Schrock, A. R. (2019.) What is civic tech? Defining a practice of technical pluralism. In P. Cardullo, C. Di Feliciantonio & R. Kitchin (Eds.), The right to the smart city (pp. 125 – 133). Emerald Publishing.

Stuetz, I. & Kure-Wu, V. (2020, August 14). Diversität von Hackathons - Wer ist das „Wir“ in WirVsVirus? Netzpolitik. https://netzpolitik.org/2020/diversitaet-von-hackathons-wer-ist-das-wir-in-WirVsVirus/.

Temiz, S. (2021). Open innovation via crowdsourcing: A digital only hackathon case study from Sweden. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010039

Thiel, T. (2017). Turnkey tyranny? Struggles for a new digital order. In S. Gertheiss, S. Herr, K. D. Wolf, & C. Wunderlich (Eds.), Resistance and change in world politics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Thiele, L., & Pruin, A. (2021). Does large-scale digital collaboration contribute to crisis management? An analysis of projects from the #WirVsVirus hackathon implemented in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic. dms – der moderne staat – Zeitschrift für Public Policy, Recht und Management, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.3224/dms.v14i2.07

Tretter, M. (2023). Sovereignty in the digital and contact tracing apps. Digital Society, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44206-022-00030-2

Urbinati, N. (2014). Democracy disfigured. Opinion, truth, and the people. Harvard University Press.

Urbinati, N. (2006). Representative democracy: Principles and genealogy. University of Chicago Press.

Urbinati, N., & Warren, M. (2008). The concept of representation in contemporary democratic theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 387 – 412. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.053006.190533

Willis, R. (2018). Constructing a ‘representative claim’ for action on climate change: Evidence from interviews with politicians. Political Studies, 66(4), 940 – 958. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321717753723

Yuan, Q., & Gasco-Hernandez, M. (2019). Open innovation in the public sector: Creating public value through civic hackathons. Public Management Review, 23(4), 1 – 22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1695884

Zar, M. & Elkin-Koren, N. (in press). The by-design approach revisited: Lessons from COVID-19 contact tracing apps. Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal.

Date received: September 2022

Date accepted: June 2023

1 This article is a fundamental revision and extension of an argument the authors made in an earlier German-language article (Berg et al., 2021).

2 Broadly speaking, the term “civic tech” refers to a set of technologies that aim to increase engagement between citizens and their government (Baack, 2018; Schrock, 2019). Civic tech activism has developed in the US context, merging activism for open data and open government with technology-oriented community engagement. Therefore, following Patel, we can distinguish between civic tech activism working towards community action and activism working towards open government (Patel, 2013; cf. Lukensmeyer, 2017).

3 From a theoretical viewpoint, civic hackathons can also be interpreted as a distinct variant of (digital) democratic innovation located at the intersection of the collaborative and consultative variants (Geißel, 2012; Elstub & Escobar, 2019). As such, they are part of the cosmos of self-selective and experimental participation processes that are also increasingly concerned with the design of digital infrastructures (Gryszkiewicz et al., 2017; Asenbaum, 2021; for a critical perspective, see Kimbell & Bailey, 2017).

4 Problems discussed within the optimistic strand mostly link to organizational questions, such as how to sustainably institutionalize the projects resulting from the hackathon (Yuan & Gasco-Hernandez, 2019; Temiz, 2021). Furthermore, the solely virtual format of pandemic-era hackathons has emphasized the need to translate the social character of the hackathon into the online environment (Menger, 2020; Happonen, 2021).

5 Compared to classic hackathons, civic hackathons generally feature a more heterogeneous group of participants, but the epistemic dominance of tech-savvy participants still easily prevails. The fact that hackathons are often held at weekends as a form of “free labour” also creates strong selection effects (Gregg, 2015; Hope et al., 2019).

6 Although there are congruencies and both can be considered interrelated, a basic distinction can be made between the representative turn (Näsström, 2011) and the constructivist turn (Disch et al., 2019). For example, while the former emphasizes the representative character of democracy on the basis of action theory, the latter particularly addresses the performative dimension of political subjectivation. Because we do not want to elaborate on the differences between the two here, we will consistently employ the term representative turn.

7 This transformation means that democratic politics today is flanked by and also complicated by a variety of non-parliamentary modes of organization – the spectrum ranges from transnational governance structures to cooperative or plebiscitary procedures. Political representation does not, consequently, become obsolete, but it changes its form and modes of functioning (see Keane, 2018; Rosanvallon, 2008). Representation is no longer viewed solely as a legally formalized and institutionalized relationship but as a structural feature of political contestation that permeates all social spheres in which political demands are formed and articulated. This includes parties, social movements, and associations. In this respect, representation is not an obstacle but, rather, the central condition of political action (Urbinati & Warren, 2008).

8 The empirically oriented analysis of performative representational processes is a familiar approach in other policy fields. Comparable examples include analyses of the different representational relationships in democratic innovations (Guasti & Geissel, 2021), of the M5S movement and its medially supported organizational structure (Diehl, 2018; cf. also Alexander, 2014), of representational processes in the diplomatic negotiations producing the Paris Climate Accord (Willis, 2018), and of the actions of non-formalized personalities (Murphy, 2021).

9 We discuss this aspect further in the context of technological mediation in section 3.3.2.

10 The survey’s results have not been published, but the raw data were kindly made available to us by the organizers and are selectively analyzed here.

11 Nonetheless, due to technical and staff overload, there were sometimes delays and problems and the complexity of the process sometimes produced frustration on the part of participants, as revealed by the participant survey.

12 Each thematic group had its own jury of five to nine members. The jury members comprised not only representatives from politics and business but also digitization experts and topic-specific actors.

13 All quotes from the interviews were originally in German and have been translated by the authors.

14 The participants themselves also predominantly shared this positive assessment, as the survey reveals, indicating that a large proportion of participants described their collaborative work on the selected projects (despite individual criticisms) as a positive experience of collectivism, solidarity, and empowerment to act.

15 The mobilization and organizational capacity of the hackathon confirmed many findings of the now well-established social science research on changes in political action in the digital constellation (for an overview, see Jungherr et al., 2020, pp. 132 – 156). Changes in the repertoire of civil society politics are central here because they increase implementation speed and improve scalability. In collective action, organizations have a new role that lies more in networking than in structuring. Participation in the context of digital infrastructures is self-selective and, to a certain extent, horizontal, but it still constitutes structures and positions of power.

16 The organizers seemed well aware that this was an issue. As such, the handbook, which aims to capture key lessons from the process for future hackathons, formulates the organizational requirements as follows: “Delegate to participants and listen: Delegate everything you can to the participants themselves. If the majority of people vote against what you are saying, just drop it. You do not have time to discuss.” (#WirVsVirus, 2020a, p. 8). While the informal exchange process between organizers and participants seems to have been intensive and cooperative based on statements made in our interviews, the only procedural change, at least according to our research, was the abandonment of the idea of a public vote due to concerns raised by participants.

17 The follow-up project #UpdateDeutschland confirms this tendency and is even more explicitly characterized by the rhetoric of innovation and the logic of the entrepreneurial state (see Staemmler and Berg, 2021; for more on the broader context, see Mazzucato, 2013).

18 The idea of organizing a vote prior to the jury decision or including a citizens’ council as an additional decision-making body was already put forward as a potential improvement by a leading member of one of the organizing entities (Interview with ProjectTogether).

Metrics

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Thorsten Thiel, Sebastian Berg, Niklas Rakowski, Veza Clute-Simon (Author)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.