Following the Beaten Track?

A Sociology of Knowledge Perspective on Information Operations

1 Introduction

The manipulation of public opinion and discourse through information operations, including coordinated influence campaigns, has attracted much attention in recent years. In public debate, governmental security strategies, and scholarly discourse, foreign information operations have emerged as one of the most apparent threats to highly connected democracies (Farrell & Newman, 2021). Such antagonistic operations, generally deployed by one state against another, have been associated with the imperiled quality of democracy and increasingly radicalized political communication at the domestic level (Benkler et al., 2018; Bennett & Livingston, 2018). Such fears have been fueled by recent examples of foreign interference in (democratic) discourse, propagation of overtly false information, as well as a changing media landscape. Though these developments certainly merit study and scrutiny, more attention should be given to the wider societal context in which they take place. Inspired by Cinelli et al. (2019), we therefore hold information operations to be the intentional and targeted use of any information, directed by one state to another state, delivered through any vector, with the intent to disrupt or otherwise hinder the targeted state’s politics, society, and public discourse. The latter is the focus of this paper. Our orientation toward a substantive notion of discourse corresponds to the basic premise that those targeted by information operations are not blank slates to be inscribed without fail but are themselves entangled in ever-evolving yet solid webs of knowledge and discourse. If and how they will be affected by antagonistically deployed information is dependent on the targets’ learned heuristics and the stocks of knowledge that are prevalent in their respective societies.

Given the heterogeneous debate around informational threats to democracy, the comprehensive account of the phenomenon that we seek to provide has to include various strands of research. Apart from international relations and security studies, there is a particularly intense coterminous research activity in political communication. In this field, however, many empirical studies tend toward atomistic and individualistic conceptions of knowledge and information. Accordingly, research has emphasized the disruptive novelty or the alleged inaccuracy of particular pieces of information (fake or false stories) on a micro level, or proliferation patterns on a meso level (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017; Vosoughi et al., 2018). Mechanisms and effects at the macro-level of public discourse have received comparatively less attention in the relevant literature (see Benkler et al., 2018 for a notable exception). This focus has changed only recently with several research articles examining this phenomenon at a societal level (Horowitz, 2021; Humprecht et al., 2020; Jungherr & Schroeder, 2021). In contrast, in international relations and security studies, the growing interest in information operations comes along with a strong emphasis on the macro level. Scholars in those fields have discussed the alleged effects on public trust in institutions or on common knowledge, often with little empirical evidence (Farrell & Schneier, 2018). While there are ways to reconcile both perspectives, for example, by studying societal processes of trust-building or knowledge generation, these steps have not yet been taken decisively or systematically.

To address this gap, this paper approaches information operations from a sociology of knowledge perspective, integrating extant literature from diverse fields of study with new empirical research. We assess the activities of RT (formerly Russia Today) in the context of the 2019 European elections. RT has been considered one of the cogs in the Russian state’s information operations apparatus by scholars and media observers alike (Elswah & Howard, 2020; Singer & Brooking, 2018). We apply a multi-method discourse analysis combining a quantitative machine-learning approach to the topical structuration of discourses (Roberts et al., 2019) with a qualitative analysis informed by the Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse (Keller, 2005). For automated, time-sensitive pattern identification, we compare a corpus of news articles by RT with articles from two established news outlets of different types and quality in two countries: France and Germany. EP elections not only stand for an increase in relevant activity (EU vs DisInfo, 2021) but also provide a comparable context of political communication for various member states of the European Union (EU).

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. After presenting the state of research on information operations, including disinformation campaigns, and the role of RT, we outline our theoretical approach and associated research hypotheses. A data and methods section follows in which we lay out our empirical research design. In Section 5, we present our findings, which are discussed in Section 6.

2 State of research

2.1 Political communication

Political communication research has been at the forefront of empirical research on the issue of disinformation, which is perceived as one essential element of information operations. International activities have mostly been this field’s subject, particularly concerning foreign (particularly Russian) interference in U.S. presidential elections. Allcott and Gentzkow’s influential study (2017) on the effects of so-called disinformation campaigns throughout the U.S. presidential election in 2016 scrutinized the consumption of disinformation based on pre-classified content, web-browsing data, and online survey data. The authors found that false stories in favor of Donald Trump were shared much more frequently than those in favor of Hillary Clinton. However, the findings suggest that the effects on users were very limited, as news consumption (including false news) was driven by selective exposure resulting in a mostly attitude-consistent effect (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017; see also Allcott et al., 2019). In similar studies, other scholars found that selective exposure is a good explanatory factor for the consumption of false news (Guess et al., 2018) or the spread of disinformation via Twitter (Grinberg et al., 2019).

While much related work has concentrated on digital media, other scholars have studied the indirect effects that disinformation diffused via digital channels has on a general public debate mediatized in hybrid media systems (Chadwick, 2013), and thus included the role played by legacy media outlets. In particular, scholars problematized how legacy outlets might take up false stories or misleading narratives. Marwick and Lewis (2017) have explained such cross-media mechanisms of disinformation in general terms, while Jamieson (2018) posits that cross-media effects and disinformation could influence agenda-setting, priming, and framing during the U.S. presidential elections in 2016, enabling the influence that Russian information operations had in this particular case.

In contrast, other researchers highlighted the vital function that legacy media, particularly public service media organizations, can exert in countering disinformation, thereby contributing to what is known as public resilience to disinformation (Frischlich & Humprecht, 2021; Horowitz et al., 2021; Humprecht et al., 2020). These contemporary trends in research indicate a growing interest in the way various states, societies, and media systems address the phenomenon of disinformation campaigns at a societal level. They correspond to the demands voiced by leading scholars in the field (e.g., Jungherr & Schroeder, 2021) that to understand the effects of disinformation in the public sphere, it is necessary to “focus on the structural, not the novel” (Benkler et al., 2018, p. 384). Interestingly, such macro-level effects have been the prime concern of disinformation-related research in the fields of international relations and security studies.

2.2 International relations and security studies

Foreign information operations have gained great attention both in the political and scholarly discourse in recent years. The concept of information operations reaches wider than mere disinformation, which can, however, be one of its essential elements. While there are competing definitions of disinformation across subdisciplines, it is logical to reserve the term for pieces of information that are objectively untrue and spread with the intent to mislead. This view follows the narrow academic definition proposed by a high-level expert group for the EU: “All forms of false, inaccurate, or misleading information designed, presented and promoted to intentionally cause public harm or for profit” (European Commission, 2018, p. 11). Yet, common threat perceptions in international conflict have clearly exceeded such a narrow understanding and are equally concerned with disruptive information and stories, or so-called “false narratives,” which might include correct information but are nevertheless shared with bad intent. As our interest is in the international dimension of the phenomenon, we find long traditions both in political practice and academic research regarding international information operations (Macdonald, 2006; Rid, 2020). Following up on such strands, we conceive foreign information operations as the intentional and targeted use of any information, directed by one state to another state, delivered through any vector, with the intent to disrupt and otherwise hinder the targeted state’s politics, society, and public discourse (cf. Cinelli et al., 2019).

In recent years, IR scholars have increasingly drawn attention to the activities of malevolent foreign actors who are said to interfere strategically in the “information space” of a given society and manipulate public discourse – or even an election outcome (Omand, 2018). Researchers have mostly focused on the alleged activities of authoritarian regimes, which have presumably included information operations in their arsenal of hybrid warfare (Maréchal, 2017; Pomerantsev, 2014). In contrast, liberal democracies are perceived as finding themselves at a disadvantage in this asymmetric conflict constellation due to their normatively rooted abstention from restrictive measures in media control (Goldsmith & Russell, 2018; Shackelford et al., 2016). Against this background, not only realist accounts but also institutionalist scholars have argued that current information operations against democracies might provoke destabilizing tendencies within the targeted systems (Farrell & Newman, 2021).

While the severe concerns resonate well with the alarmist tone in public discourse, more critical and differentiated voices are questioning the assumption that there would be readily available tools for malevolent actors to significantly sway public opinion through information operations (Lanoszka, 2019; Rid, 2020). For both Rid (2020) and Lanoszka (2019), scenarios of foreign actors injecting neatly manipulated pieces of information and thereby diverting public discourse with immediate and sensitive effects seem highly unlikely. The recipients of disinformation are not “impressionable blank slates” (Lanoszka, 2019, p. 236) to which any novel piece of information will adhere equally well, nor are the propagators of disinformation clinical operators who avoid contamination from their work. As Rid (2020) says, “the stronger and more robust a body politic, the more resistant to disinformation it will be – and the more reluctant to deploy and optimize disinformation” (p. 11). From this perspective, the main function of information operations is seen in the creation of doubt, rather than actual persuasion (Gerrits, 2018; Rid 2020).

Regarding the predispositions of the target society, Lanoszka (2019) carved out the idea of a “second barrier” that successful information operations must penetrate. According to the author, this “second barrier relates to the pre-existing ideological commitments and mindsets of those individuals who may be exposed to disinformation” (Lanoszka, 2019, p. 228). From this perspective, Lanoszka fundamentally questions the strategic use and effects of information operations as “neither leaders nor average citizens are easily receptive to disinformation” (Lanoszka, 2019, p. 238). While we build on Lanoszka’s work, we question the theoretical foundations of these crucial resources for public resistance to foreign information operations. We maintain that conventional wisdom and pre-existing mindsets are not features expressed by individual actors but are instead dispositions obtained from social stocks of knowledge through processes of socialization. Before we introduce our sociology of knowledge-oriented approach to focus on the structural level of discourse and knowledge, we examine RT as our object of empirical inquiry and related research.

2.3 RT as a potential vector for information operations

RT was founded as Russia Today in 2005 as a more Russian-focused alternative to Western media, but it gradually changed from a news outlet to one of the branches of the Russian state’s information operations apparatus abroad (Singer & Brooking, 2018). Accordingly, recent scholarly work has focused on the role of RT as a propagator of conspiracy theories (Yablokov, 2015). This view is supported by Elswah and Howard’s (2020) study based on interviews with RT employees regarding the objectives and methods of RT. The authors identify RT’s interest in spreading conspiracy theories depicting Western states as flawed to generate controversy, thereby increasing Russia’s prominence. RT’s role in information operations has also been noted by journalistic integrity watchdogs. However, a lack of systematic research can partly be explained by the notorious difficulty to accurately “measure the channel’s success and influence” (Yablokov, 2015). The recent geopolitical situation, however, has put new public scrutiny on RT, leaving little doubt about institutionalized politics’ perception of RT as an agent of foreign information operations. Already in 2015, the EU installed its East StratCom Task Force with the explicit goal to counter Russian propaganda. 1 France has put restrictive measures on Russian outlets such as RT or Sputnik news with its 2018 law against false information (so-called “loi infox”). In Germany, the supervisory authority for the media sector banned RT’s German television channel in February 2022 as it did not operate under a proper license. Finally, after Russia started its war against Ukraine, in March 2022, the EU included a general ban on RT in its sanctions package against Russia (Regulation [EU] 2022/350). This ban was challenged by RT France in the European General Court, but it was upheld in the Court’s ruling on 27 July 2022 (case T-125/22).

Despite all evidence for malevolent activity and the political contention facing RT, it would not be appropriate to disqualify the entire news provision of RT as disinformation. Answering the question of whether a news outlet as such is propagandistic would require a thorough analysis of the veracity and presentation of its news output, which is not the goal of this paper. However, in the case of RT, we consider the existing literature to be convincing in establishing RT as a hybrid and dynamic news outlet that is inclined toward disseminating disruptive content. In what way RT provided a mix of proper news, aligned to the public discourse of the targeted society, and disruptive content, however, is a relevant question for this paper as is its corollary of how this practice might be key to understanding the way foreign information operations affect societies.

3 A sociology of knowledge perspective on information operations

To study the structural dimension of information operations, we propose a theoretical reorientation toward a sociology of knowledge perspective. Such a theoretical perspective helps avoid atomistic and individualistic misconceptions of information and knowledge prevalent in political sociology (see, e.g., Lupia & McCubbins, 1998) and political science more generally (for a critical discussion, see Dunn Cavelty, 2008; Schünemann, 2014, pp. 58-75, 2022).

Classic accounts in discourse theory and sociology of knowledge have made their basic assumption crystal clear that knowledge – and even the perception of reality – is socially constructed (Berger & Luckmann, 1991). It is materialized and processed in discourse and practice (Foucault, 2002). Thus, knowledge is not to be understood as the sum of single bits of information (nor disinformation). Knowledge is also not located at the individual level but at the level of society. As Scheler remarked, all knowledge is defined by a society and its structure (Scheler, 1960, p. 52). Knowledge is thus not a feature of the individual nor at their disposal. Individual actors obtain and appropriate knowledge through socialization in various community contexts (Berger & Luckmann, 1991, pp. 149 – 166). Against this backdrop, information as such has no meaning and thus would not exert any effects on a person, not to mention a social group or society as a whole. To take effect, it has to be interpreted based on social stocks of knowledge collectively built and preserved.

For information operations, we regard modern informational environments concerning the macro dimension of public discourse as complex, discursive formations. In contrast to many voices in the political and academic debate, we reject any understanding of information environments or public discourses as tabulae rasae wide open for discursive infiltration – even in liberal democracies. On the contrary, we expect the respective social stocks of knowledge to serve as effective filters of perception, providing a target society with a type of protective skin (akin to Lanoszka, 2019) discriminating against the foreign and the unknown (sometimes wrongly).

Thus, the theoretical reorientation introduced above leads us to expect that malevolent actors attempting to influence a foreign public necessarily adapt to the prevalent discourses in a targeted public, addressing elements of culturally specific stocks of knowledge. Instead of injecting unheard-of pieces of thought and information, we expect them to identify and attack preexistent discursive fault lines and vulnerabilities of a given society. Thus, we support a position expressed by French sociologist Jacques Ellul (1965) regarding the more general phenomenon of propaganda in the 1960s: “Propaganda must not only attach itself to what already exists in the individual, but also express the fundamental currents of the society it seeks to influence” (p. 38). Therefore, we would expect the agents of information operations to generally align their agenda and framing to the public discourse represented in the mainstream mass media. Only through this kind of strategic emulation would they be able to attract sufficient attention and outreach to serve as a news outlet more broadly and influence public opinion and discourse.

This expectation draws on structural features at the meso level, especially the privileged role played by various media actors that must not be neglected when studying macro-level discourse. First, social communication, especially what we understand as public discourse, is necessarily mediated (Couldry & Hepp, 2017). This structural condition provides media outlets with privileged positions of differing reach for channeling and filtering content and information, allowing them to co-determine what is addressed in the public arena, and at what time and at which intensity. Second, building upon this general rule, it is obvious that digitalization has transformed structures and mechanisms for the constitution of a public sphere, and thus public discourse, in several ways (Chadwick, 2013; Jungherr & Schroeder, 2021). We acknowledge these developments and concede that they have complicated the identification of public discourse as well as the reconstruction of its formative rules, but this does not revert our basic assumptions.

Objections to our theoretical position might also build on empirical insights showing that scandalous news expressed in a negative tonality are likely to attract more attention and be spread more widely than positive messages. While such generic behavioral rules are certainly compelling, they are not independent and thus compatible with a sociology of knowledge perspective. Early accounts of the theory have highlighted that these kinds of instincts cannot themselves be regarded as free from social construction (Mannheim, 1964, p. 365). Thus, similar to atomistic conceptions of knowledge, paradigms of instinctive reactions can provide half of an explanation at best (Anderson, 2021). While the informational soup might indeed be spiced universally to trigger individual instincts, we might still observe relevant variation concerning the substantial ingredients selected according to local tastes or customs.

Building on our social-constructivist theory, we expect foreign information operations to align with socio-culturally specific patterns of public discourse. As to the temporal variation, we expect RT to follow public discourse on divisive topics, rather than plant the seeds for a dominant topic (H1). Moreover, we hypothesize that RT addresses divisive issues that promise affective reactions (H2). We finally expect RT’s information operations to reflect alignment to prevalent interpretative schemes and knowledge elements within certain topics (H3). We expect all three hypotheses to hold in different national media systems, thus requiring a comparative research design.

Therefore, we can formulate the following hypotheses:

- Hypothesis 1: RT news coverage follows the agenda of public discourse as represented by established news media.

- Hypothesis 2: RT news coverage emphasizes divisive issues that promise affective reactions.

- Hypothesis 3: RT’s framing aligns with prevalent interpretative schemes and knowledge elements in the respective national public discourse as represented by established news media.

4 Data and methods

This paper empirically tests the aforementioned hypotheses through an analysis of a composite corpus of news articles from Germany and France published between 23 February 2019 and 30 June 2019. 2 These dates comprise the run-up to and the aftermath of the 2019 European elections campaigns. Two main reasons support the selection of this period. First, election campaigns, including EP elections, have served as prime contexts for foreign actors to conduct large-scale information operations (European Parliament, 2019). Hence, we expect an increased activity of this sort during the selected period. As it is beyond the interest and scope of this paper to assess the veracity and factuality of each article published by RT to determine whether it is “disinformation,” RT is assumed at a more general level as a vehicle for Russian information operations in Western European countries. This is in correspondence both with academic literature and political assessments. Thus, we are not concerned with the amount of disinformation disseminated during our observation period, but rather the techniques employed by RT to position itself in public discourse. Second, we selected this research period because national elections in all member states occur at about the same time, providing a similar context of political communication across EU countries and thereby making our cases more comparable.

RT is a particularly useful case study due to its (former) presence in multiple countries and multilingual content. This audience reach allows for comparisons on a country- and language-level basis, which will help identify any potential country-specific features of disinformation campaigns. The two countries, France and Germany, were chosen because they appeared as the main targets of information operations attributed to Russia (EU vs DisInfo, 2021). RT versions have been available in both countries (until March 2022) and, according to respective reports, have served as important outlets for spreading disinformation. Finally, another advantage of our case selection is that by assessing information operations in non-Anglophone countries, we make a different and complementary contribution to the existing literature that has already covered the Anglosphere extensively.

To gather a relevant sample of mainstream news media to serve as a representation of the respective public discourse, we built corpora with news articles from one regular newspaper and one tabloid newspaper: Die Welt and Bild for Germany, and Le Figaro and FranceSoir for France, respectively. The articles used in the dataset were scraped from the German and French websites of RT, as well as from the FranceSoir website, while the articles from Die Welt, Bild (+ Bild am Sonntag) and Le Figaro were downloaded via the LexisNexis database. As mainstream news outlets cover a much broader range of issues than RT, which is mostly focused on political news, we used the outlet-assigned sections for filtering news articles that did not fit the orientation toward political news. 3 We also excluded articles below a length threshold of 180 words for all corpora as brief news items do not allow for substantial analysis. In addition to the text bodies, we utilized metadata in all subsets for the measurement of covariate effects such as source (the name of the outlet) and date (the exact date of the publication). Additionally, headlines were kept for qualitative topic evaluation and labeling. The subsets were curated and aligned to combine them into an integrated dataset per national case. Table 1 provides an overview of the number of articles included per outlet and case.

Concerning the resulting dataset, one could of course object that our selection is biased toward a right-wing conservative spectrum and does not fully represent the mainstream media discourse. Although we agree, this accent in our selection of outlets is deliberate as we would expect RT mostly to address readers in that spectrum. With this focus, we can detect meaningful variation regarding our research question rather than differences produced by the divergent ideological positions present in the general public discourse.

Table 1: Composition of corpora for both cases

|

Germany |

France |

||

|

Die Welt |

3260 |

Le Figaro |

3954 |

|

Bild |

1195 |

France Soir |

1252 |

|

RT Deutsch |

2886 |

RT France |

2123 |

We used the R programming language’s Quanteda textmining toolbox (Benoit et al., 2018) for preparing the text corpora. We removed stopwords and URLs and compounded frequent collocations (e.g., first and last names) before employing Structural Topic Modelling (STM) (Roberts et al., 2019). STM is a viable choice for our analysis, as it allows modeling covariate effects on topic distribution for both the various news outlets, as well as the timeline in which trends and/or clusters of topics emerge. Therefore, we utilized both the outlet and the day of publication as prevalence variables. To allow for non-linear effects on the topics, the day variable was splined as suggested by STM’s authors (Roberts et al., 2019). For reproducible and less initialization-sensitive models, we chose STM’s spectral initialization method (Roberts et al., 2016). Even though progress has been made in utilizing machine-translated documents for quantitative text analysis (Vries et al., 2018), we ran separate topic models for the French and German corpora to better account for the expected socio-cultural differences. 4 Finally, we utilized the STM package’s native regression functions to estimate the effects of our prevalence variables and account for the specific uncertainty introduced in model fitting (Roberts et al., 2019). The R package ggplot2 was used for visualizations (Wickham, 2010).

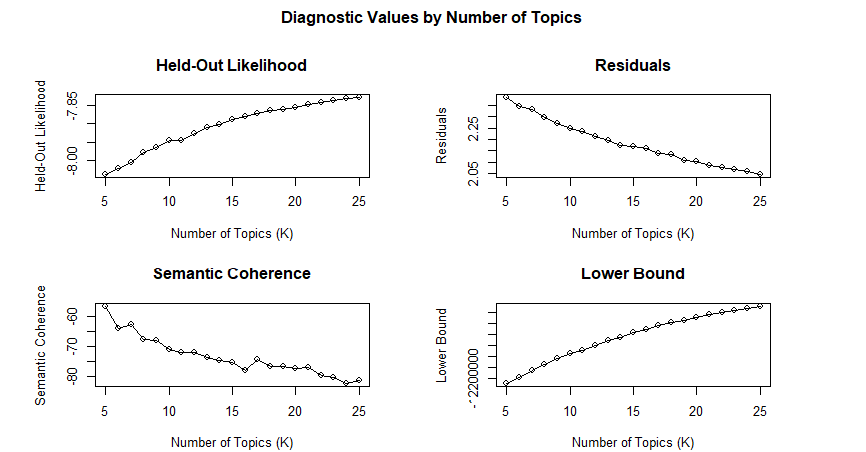

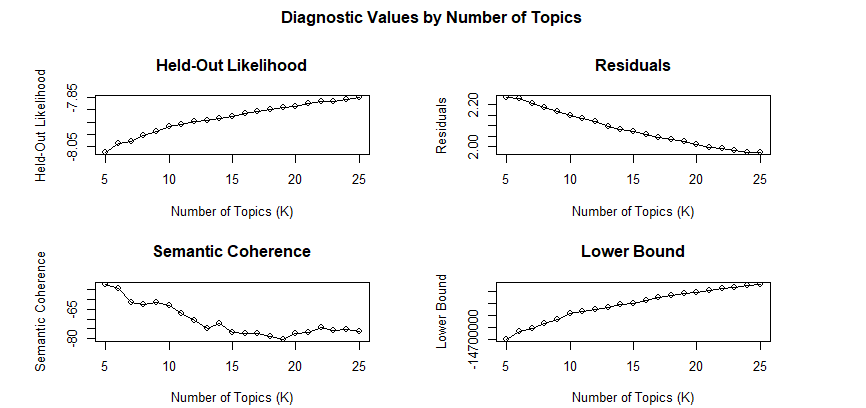

As suggested by STM’s authors (Roberts et al., 2019), we evaluated topic models (with k = 5 up to k = 25) based on key performance statistics (exclusivity, semantic coherence, residuals, held-out likelihood) and selected three models for France and Germany respectively. These statistics can be found in Appendix A. We labeled topics for all three models and evaluated consistency and validity based on an interpretative classification. To label the identified topics, we inspected the top terms and headlines of articles with high topic proportions (theta ≥ 0.7) per topic per case. We reevaluated the model and relabeled the topics over several rounds of reading and interpretation before settling on a model with 12 topics for the German and a model with 14 topics for the French case.

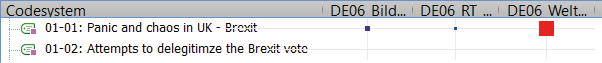

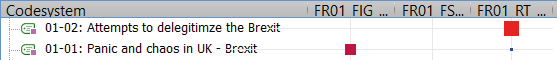

For the fine-grained qualitative analysis of topic-specific document samples, we chose the sociology of knowledge approach to discourse (Keller, 2005, 2013) as a theory-consistent methodological orientation. Via qualitative inquiry, we could identify recurrent interpretative schemes. Based on Keller’s fundamental typology, we focused our analysis on basic frames and narratives. Defined as specific structures of meaning-making, frames tell or invoke a story in that events are ordered along a supposed chronology, suggesting causal relations. For instance, some documents portray the political situation in the United Kingdom regarding Brexit implementation as chaos and paralysis caused by a misled referendum (e.g., Collomp, 2019). Other sources depict the success of the Brexit Party in EP elections as an embarrassment for people who would try to delegitimize the democratic vote in the referendum (e.g., “Le parti du Brexit“, 2019). These two examples demonstrate two competing frames. In contrast, the story of the Venezuelan interim president Guaidó allegedly having orchestrated a coup against the democratically elected Maduro government (as told e.g., in “Guaidós Putschversuch gescheitert”, 2019) would qualify as a narrative.

We filtered documents by picking the 10 documents with the highest topic proportions for each topic and outlet per case. Selected documents have been analyzed by close-reading and consecutive rounds of coding with an inductively developed codebook (Appendix D). A minimum of five documents per outlet and topic were analyzed until saturation was reached, up to a maximum of 10 documents. Codebook development and coding were exerted in the MAXQDA software environment.

5 Results

5.1 Topic modeling and quantitative analysis

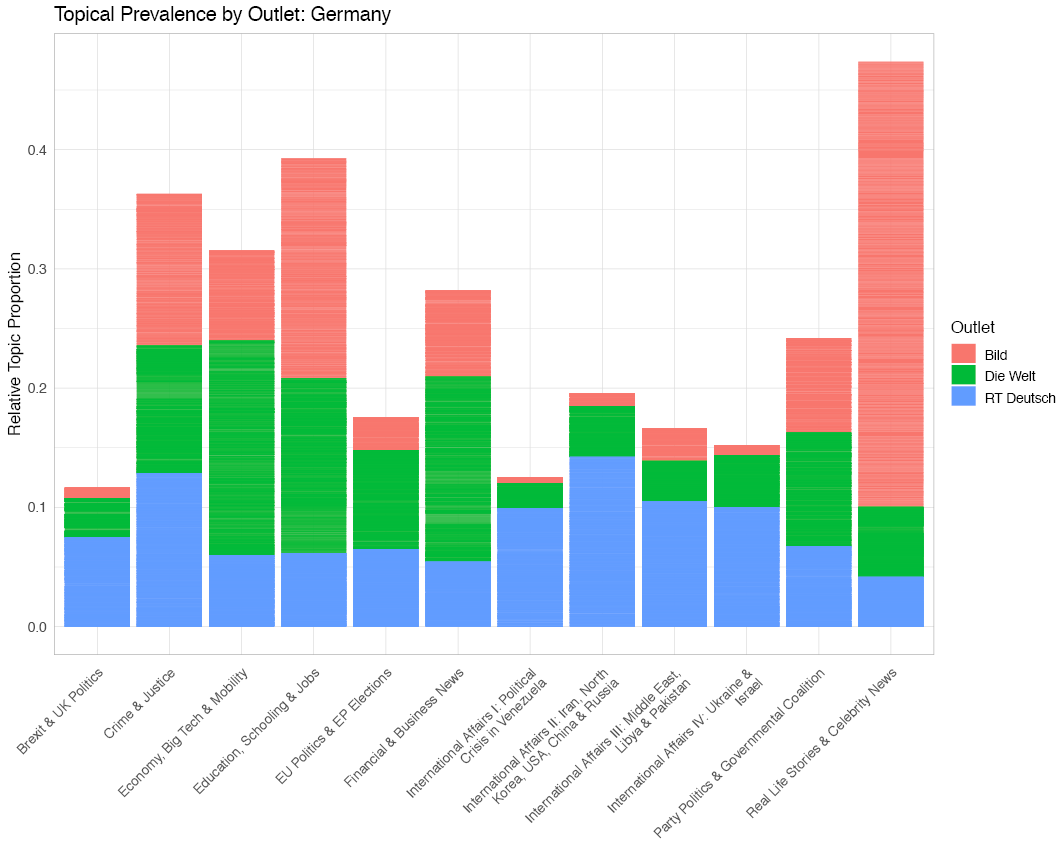

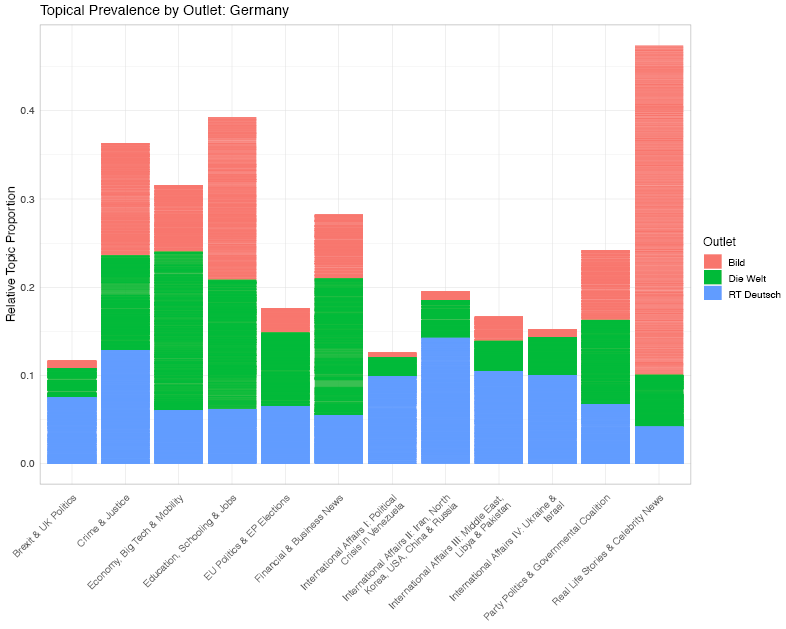

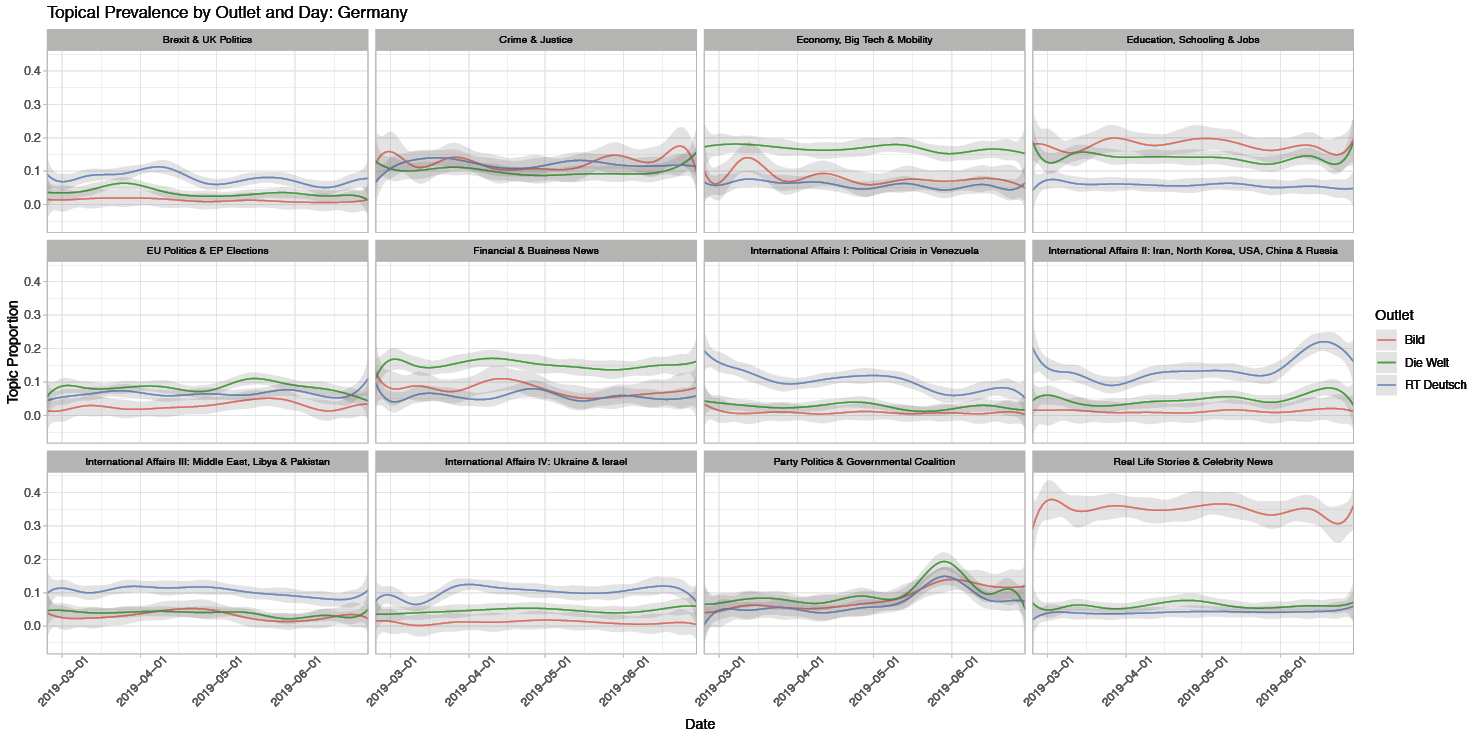

We start our presentation of results with a comparison of the relative topic proportions across the three different outlets per case, which accounts for the differing number of articles between outlets. 5 Figure 1 shows this overview of the German case with its 12 topics. First, the figure reveals that topic proportions diverge between the outlets. There are only a few topics for which relative topic proportions are similar for all three outlets: the topics “Crime & Justice” and “Party Politics & Governmental Coalition.” Proportions are similar for “EU Politics & EP Elections” at least for RT Deutsch and the quality newspaper Die Welt (Welt), while the tabloid Bild produced less content on the topic. Economic and financial topics are mostly covered by Welt articles, while unsurprisingly, “Real Life Stories & Celebrity News” are a specialty of Bild, with the respective topic proportions unmatched by Welt or RT Deutsch. In comparison to the other outlets, RT Deutsch is preoccupied with international affairs. Typical international content produced four different topics covering political crises in Venezuela, Ukraine, and the Middle East as well as a major power play between the United States, China, and Russia.

Figure 1: Relative topic proportions by outlet in the German corpus. Topic proportions are normalized over the number of articles per outlet.

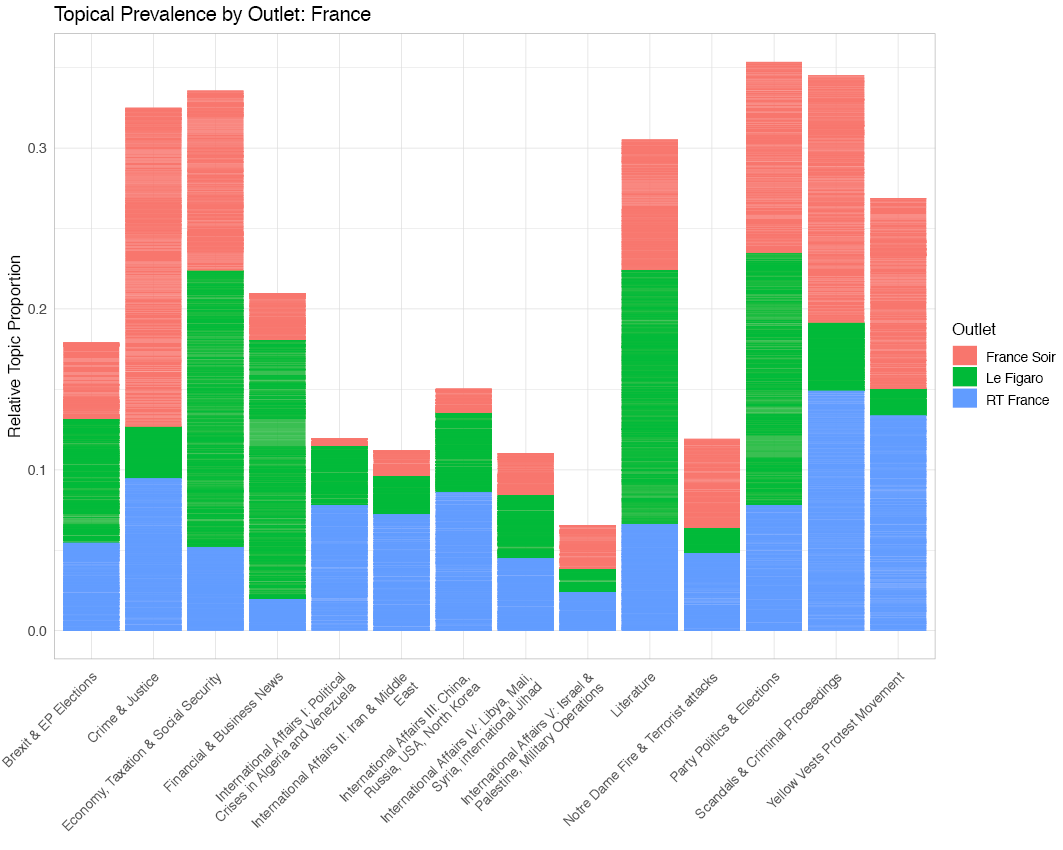

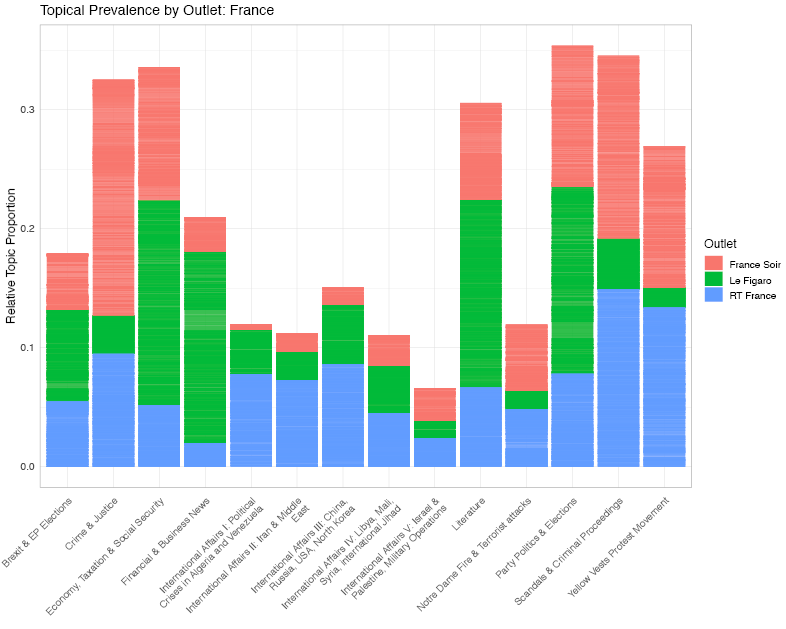

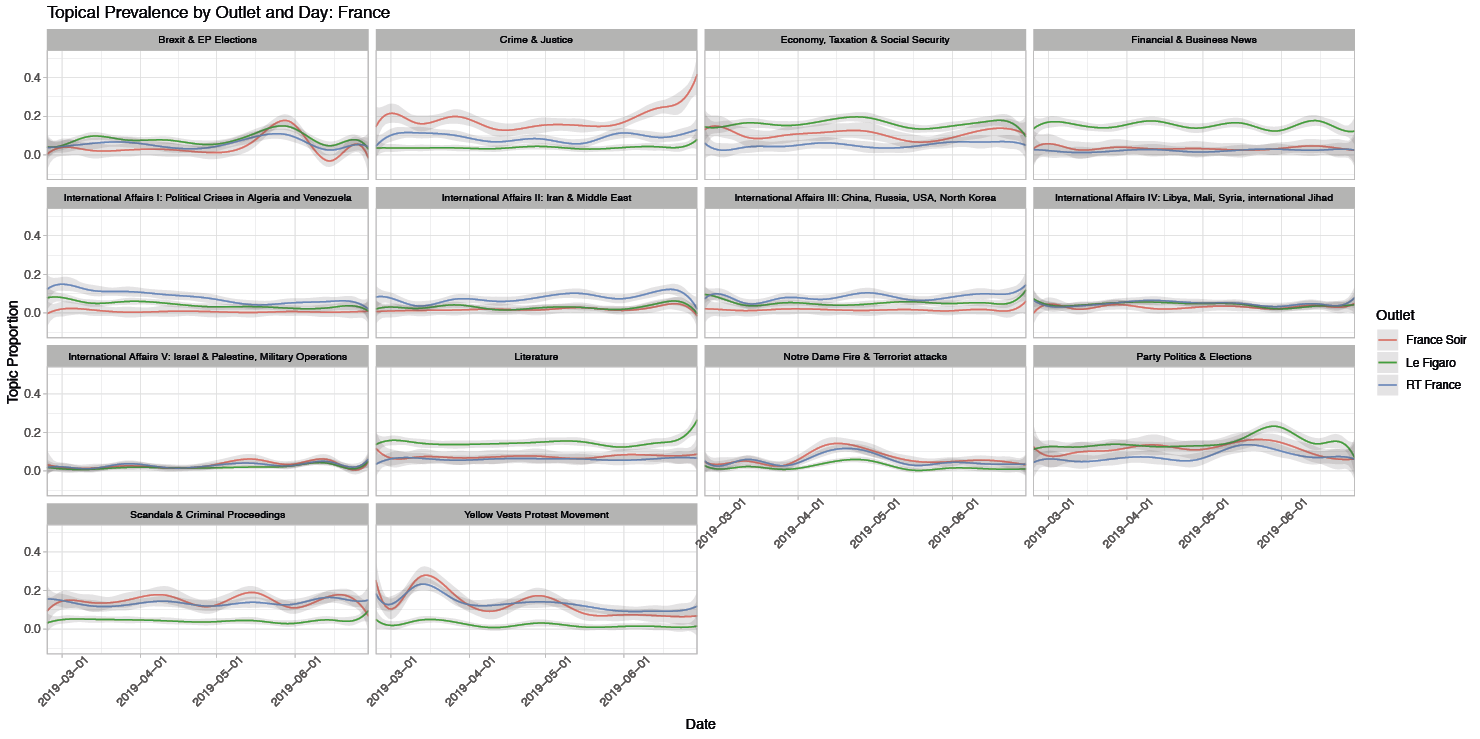

The overview of relative topic proportions for the French case based on the selected model with k = 14 topics can be found in Figure 2. We find more or less similar shares for the topics “Party Politics & Elections” and “Brexit & EP Elections” while relative topic proportions diverge for the other topics. This is again particularly true for at least four of the five topics that are related to international affairs and crises. The French tabloid-like paper FranceSoir is dominant in the “Crime & Justice” topic. Again, the quality newspaper shows a higher news production on economic and financial issues. Interestingly, while both topic models (on the French and German cases) show remarkable similarities at this categorical level, there is at least one country-specific topic related to the so-called yellow vest protests that shook the country. The figure shows high topic proportions for the tabloid as well as RT France. The “Scandals & Criminal Proceedings” topic also seems country-specific, especially regarding its second focus. Both topics (“Yellow Vests Protest Movement” and “Scandals & Criminal Proceedings”) are striking given the high relative topic proportions for RT France.

Figure 2: Relative topic proportions by outlet in the French corpus. Topic proportions are normalized over the number of articles per outlet.

At this abstract level of analysis, topical structuration and thus the basic categorical scheme appears to be similar for both national cases: France and Germany. Moreover, we find similar patterns of activity for RT outlets in both cases. This harmonious comparative picture is, however, somewhat troubled by the unique topics in the French case. For both topics, we see remarkable activity in RT France. The news production that produced the yellow vests topic is particularly grounded in the specific context of French politics and social movement protests throughout our research period. Considering temporal variation, metadata analysis allows for the time-sensitive analysis of the topical prevalence between the three outlets for each case. Figure 3 is a respective multiplot for the German case, and Figure 4 offers an overview of the French case. 6

For the German case, we observe that for most topics, RT Deutsch follows a similar trend line as given by at least one of the other outlets. The “Brexit & UK Politics” topic might show some deviance for RT Deutsch, but this is at a rather minor level of topic proportions. Again, as for the static overview, we see that RT Deutsch seems to play out its particularity with respect to international affairs issues, whereas the numbers for RT seem to be somewhat decoupled and far exceed the values of the other outlets. These findings are supported by the results of the regression found in Appendix C-I., which show a significant positive impact of the outlet RT on the majority of these topics even when controlled for the day. However, in these remarkable cases, similarities in trend lines are seen in comparison to the other outlets (see, e.g., the topics “International Affairs I” and “International Affairs II”).

For the French case, relative topic proportions over time reveal similar trend lines for RT France with at least one of the other outlets, often both of them. While in correspondence to what we have learned from the static view, RT operated at a different level of activity concerning international affairs-related issues, the gap between RT France and the other outlets is generally bigger for International Affairs I, II, and III, but less so for International Affairs IV and V. Compared to the German case, this observation shows a partly significant but lower impact for the outlet RT when controlled over time, which is supported by the regression results found in Appendix C-II. Additionally, for the two country-specific topics with higher topic probabilities for RT France, news production of the alleged propaganda outlet is not divergent from established news media but is instead aligned to the general trend line.

Results at this abstract level of analysis as depicted by Figures 1 – 4 allow for preliminary assessments concerning the first two of our hypotheses. We can make an affirmative assessment for Hypothesis 1: Generally, news production of RT outlets tends to follow the trend lines shown by mainstream news media topic coverage. Some remarkable exceptions are noted, however, regarding international affairs-related issues, especially for the German case study. In contrast, we find a mixed picture for Hypothesis 2. International affairs, while generally being standard topics on the news agenda, cannot be regarded as particularly divisive issues in public discourse and politics. However, RT outlets focus on international topics in their news production. Nevertheless, the two country-specific topics for the French case, in particular, the yellow vest movement, suggest that RT France identified a country-specific divisive issue to address and thereby provoke affective reactions, attempting to contribute to social unrest in this particular case.

5.2 Qualitative analysis

For our qualitative inquiry, we selected several topics for each case. Given our research period and the reasoning behind it, we elected to conduct an in-depth examination of the then-ongoing EP election campaign in each of the cases. For the German case, we investigated “EU Politics & EP Elections” plus “Brexit & UK Politics.” For the French case, we observed “Brexit & EP Elections” plus “Party Politics & Elections.” Moreover, we decided to analyze two out of the four and five topics related to international affairs. We based our selection on topic proportions and the significance of RT’s preoccupation as well as the comparability between the cases. We selected “International Affairs I: Political crisis in Venezuela” and “International Affairs II: Iran, North Korea, USA, China & Russia” for Germany as well as “International Affairs I: Political Crisis in Algeria and Venezuela” and “International Affairs III: China, Russia, USA, North Korea” for France. To shed light on another field of news coverage expected to include a high amount of affective content, we selected “Crime & Justice” for the German case and “Scandals & Criminal Proceedings” for the French case. Finally, given its peculiarity, we additionally selected the topic “Yellow Vests Protest Movement” for the French case. Visual synopses of within-case comparisons per topic are given in Appendix E.

5.2.1European politics and EP elections

The topical corpora related to European Politics and EP Elections show many similarities in both national cases. However, the within-case comparison also reveals some interesting differences. Many articles in both samples (“Brexit & UK Politics” for the German, and “Brexit & EP Elections” for the French case) deal with the then ongoing Brexit negotiations. In all outlets (in particular the mainstream media outlets), the political situation in the United Kingdom is repeatedly depicted as chaotic (“Brexit-Chaos,” e.g., Bolzen, 2019; “Brexit-Irrsinn,” e.g., Block, 2019), with the political system in paralysis (“la paralysie politique à Londres,” Collomp 2019). Articles reproduce the narrative of leading British politicians who are increasingly panicked by a no-deal Brexit scenario at the doorstep yet unable to find a political compromise allowing for a deal with Brussels. The German Bild, for instance, posed the rhetorical question: “How can the political tug-of-war about the British EU exit get any crazier?” 7 (Kleine et al., 2019).

Regarding intergovernmental negotiations on further extensions of the deadline for a deal, in major newspapers, the French government’s strict position is reported mostly in an affirmative manner (Collomp, 2019). The government’s clear stance is portrayed as a legitimate position toward domestic chaos in the UK. Common frames of the situation ascribe responsibility for the situation to the United Kingdom and its political elites. However, a closer look reveals a different framing for RT. In clear contrast to the mainstream media critically commenting on the Brexit decision, similar criticisms cannot be observed for RT articles. In contrast, RT authors criticize Remainers for not accepting but rather seeking to delegitimize the direct democratic decision. Opinion polls showing the Brexit Party ahead and its later victory in the election are reported with grains of satisfaction and irony, relying on its interpretation as a clear electoral confirmation of the referendum outcome (“Le parti du Brexit“, 2019).

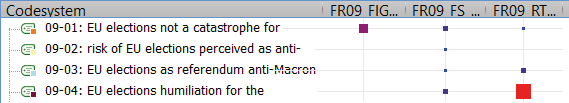

Regarding the EP elections, articles in the German corpus overall show a greater issue-orientation, while the elections in France were dominated by domestic party politics, as they were the first national elections since the successful presidential campaign of Emmanuel Macron. With the transition of the French party system evolving further and the personal engagement of President Macron in the campaign, all outlets discussed the risk of the elections turning into a protest vote against the government. The framing in many RT France articles, however, is significant in the way they explicitly took up the frame of an “anti-Macron referendum” that had been established by right-wing extremists during the campaign. In this vein, after the slight victory of the right-wing Rassemblement National ahead of Macron’s list, an article stated: “Emmanuel Macron has turned this electoral challenge into a referendum on his political performance and the eventual defeat justifies the following assessment: the government finds itself weakened after these European elections” (”désaveu pour La République en marche”, 2019).

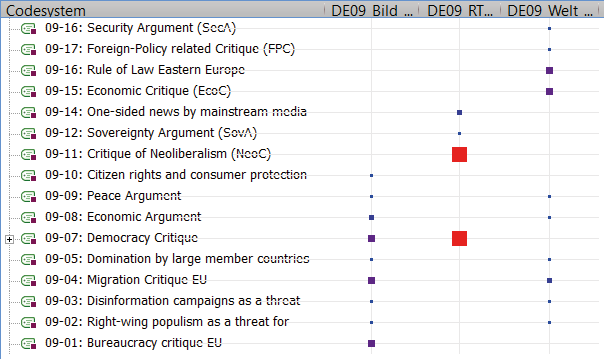

In the German corpus, however, numerous articles regard the pros and cons of EU integration and current EU policies. For Bild and Welt, we find both positive and critical assessments and perspectives illustrated by statements and quotes that reproduce common frames and narratives. These include the “EU as a peace project” or an “economic success story” on the one hand, and frames of an “emergent transfer union with little orientation toward financial stability,” so-called “faceless bureaucrats,” or the often-diagnosed democratic deficit on the other hand. Although such frames and narratives are also part of the discourse reproduced by RT, reported assessments are exclusively critical. Statements include frames that are typical for right-wing or left-wing Euroscepticism such as the narrative of a “European superstate undermining national sovereignty” or the allegedly “neoliberal” character of EU economic governance (e.g., Ungar, 2019).

5.2.2International affairs-related topics

The international affairs-related topics that are of key importance for RT content production the French and the German case reveal a similar orientation toward major crises on the international scene as well as geopolitical rivalry and conflict between major powers such as the United States, China, and Russia. We can observe more coverage and intensive discussion on the political turmoil in Algeria for the French case when compared to the German case. This comparatively high interest in the issue is mirrored by all three outlets under analysis, including RT. This preoccupation can be explained by the colonial history of Algeria, the close relations between both countries, and especially parallel protests being held across France about the situation in Algeria in the weeks under study.

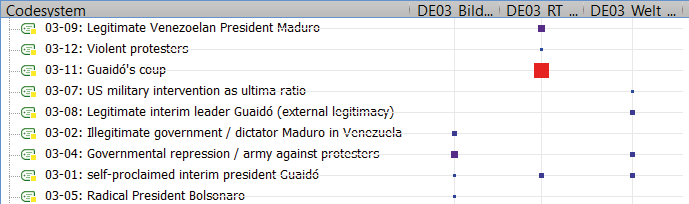

Within-case comparisons between outlets for the respective subsamples show some of the clearest divergences in how the respective issues are discussed with no or only little overlap in crucial frames of the respective situations, especially for the reporting of the Venezuelan crisis, but also the Iranian crisis and major power rivalry. Starting with the Venezuelan crisis, this issue was extensively covered by German outlets in the spring of 2019. Bild and Welt articles portray the turmoil that was driven by opposition forces around self-proclaimed interim president Guaidó (“Hoffnungsträger,” ” Blutiger Machtkampf”, 2019) as a legitimate rebellion against the repressive regime of authoritarian leader Maduro (“dictator,” Käufer, 2019).

According to the prevalent narrative, President Maduro had committed electoral fraud to stay in office and then used excessive violence to smash democratic protests: “Maduro has once more shown that he is ready to literally walk over dead bodies if necessary for staying in power” (Käufer, 2019). Such interpretative schemes are countered by the discourse produced in RT articles. From this perspective, the actions taken by oppositional forces around Guaidó are regarded as part of an illegitimate coup against the democratically elected government of President Maduro: “Also the most recent coup attempt by the self-proclaimed ‘interim president’ of Venezuela, Juan Guaidó, against the elected President Nicolas Maduro failed” ( “Oppositionsführer Guaidó und López”, 2019). Moreover, in clear contrast to mainstream media, the protest movement is depicted as violent and steered from abroad. Accordingly, U.S. engagement is portrayed as an illegitimate foreign interference in Venezuelan domestic affairs ( “Guaidós Putschversuch gescheitert”, 2019).

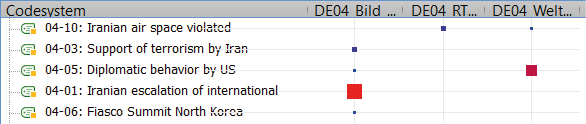

In another subcorpus with documents dealing with international affairs from the German case, the articles in our sample mostly covered the conflict between the United States and Iran after U.S. President Trump had canceled the Iran nuclear deal initially approved by his predecessor in 2015. The issue was brought to the fore by a row of violent incidents, in particular the shooting of a U.S. drone by Iranian troops in June 2019. In contrast to RT, Bild and Welt articles put the incident in the context of the overall conflict. As to the general framing, the escalation of the conflict is attributed to the Iranian regime, at least in Bild articles (e.g., Schippmann & Bräuner, 2019). In both outlets, articles interpret the renunciation of a military counterstrike by the Trump administration as diplomatic behavior (e.g., WELT, 2019). In contrast, RT articles reported statements that depict this act as an admission of guilt. RT articles also repeatedly refer to sources that argue for a violation of the Iranian airspace by the U.S. drone: “US fiddle about the shooting of a 170 million dollar drone” (“US-Mauschelei um iranischen Abschuss”, 2019).

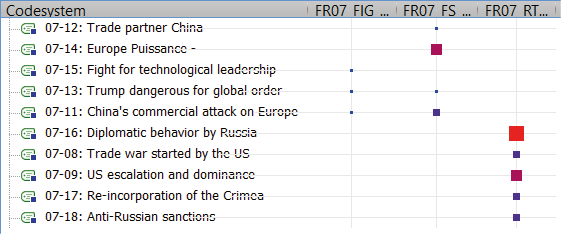

Shifting to those documents wherein major power rivalry is the explicit focus, including either the trade conflict between China and the United States or the conflict between Russia and the West (EU and the United States) following the Crimea annexation in 2014, a within-case comparison reveals a more clear divergence between RT and the mainstream outlets. For both crisis contexts, the mainstream outlets include balanced interpretations. Thus, for instance, China is depicted as an important partner in international trade relations for France and the EU, while at the same time its international outreach especially in the framework of its New Silk Road Initiative is seen as a potential threat and a commercial attack on Europe (e.g., “L’Union européenne se saisit de la 5G”, 2019). In their critical framing of the U.S. position and particular policies, especially the emphasis put on an autonomous policy definition by the European side in international trade policy but also foreign and security policy (“Europe Puissance”), several articles in French legacy media outlets take up core elements of socio-specific stocks of knowledge and interpretative schemes (e.g., “L’Otan a 70 ans”, 2019). While presenting some potentially compatible elements to French foreign policy discourse, namely the critical framing of U.S. dominance, this criticism appears much more outspoken and one-sided in RT outlets. Thus, the prevalent narrative in RT articles would be that the United States was responsible for the escalation of both crises. For instance, an RT Deutsch piece concerned the crisis with Iran: “US opt for escalation and block the road toward a diplomatic solution with a new wave of sanctions” (“USA setzen auf Eskalation“, 2019). In particular, Western sanctions against Russia (“anti-Russian sanctions”) are depicted as illegitimate elements of a US-led strategy for global dominance (e.g., “Poutine et Xi font front commun”, 2019). The Russian government is instead attested a diplomatic behavior, even toward the Ukrainian government after the election of President Zelensky in April 2019 (“Poutine salue la politique de détente“, 2019). The interpretation of Russian activities during the Ukrainian crisis is markedly different for RT. The annexation of the Crimea, which is depicted in legacy media outlets as a red line crossed by the Russians clearly violating international law, is portrayed in RT articles as a legitimate “re-incorporation” into the Russian state after a democratic referendum that had been won by the respective constituency (“A Moscou, Xi et Poutine célèbrent la lune de miel”, 2019).

5.2.3Crime & scandals, protests in France

Qualitative analysis of topics related to criminal offenses quite naturally produces variation between the national cases as the expected outcome. News coverage is incident-driven on a domestic scale and thus follows a particular national media logic with only few cross-border incidents to be reported. Thus, variation is not surprising here. However, the preoccupation of German media outlets in the sample with violent attacks purportedly committed by immigrants is an interesting finding. In this common framing of security incidents as a migration-related problem, RT is similar to the tabloid Bild which seems to be even more active and explicit in this regard (e.g., Keim, 2019; “Brutale Gruppenvergewaltigungen in Düsseldorf“, 2019). In contrast, comparable cases are not as prominently reported in the newspaper Welt.

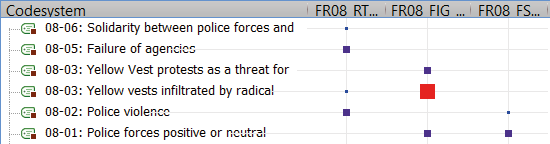

The respective topic selected for the French case is instead oriented toward political scandals. In particular, a political affair about ex-security officer and deputy chief of staff Alexandre Benalla is of key importance. 8 The Benalla affairs were related to the issue of the yellow vest protest movement that has been additionally selected for qualitative analysis due to its peculiarity for the French case and the likelihood to attract emotional and affective reactions. Although coverage of the issue in RT is similar to what is provided by the quality newspaper Figaro with respect to extent and framing (namely highlighting the political character of the affair), we have a more mixed picture with respect to within-case comparison between the outlets. The framing of the protest events toward the violent engagement of police forces appears only in FranceSoir and on RT. A more positive or neutral framing of police forces and their engagement can be found in the Figaro articles and again also in FranceSoir articles. Even in the RT corpus, we find individual articles that emphasize the solidarity between normal protesters and the police. Therefore, in RT articles only, an opposition is carved out more clearly between the people including protesters and police on the one hand and the political establishment on the other (cf. Rives, 2019).

6 Discussion & conclusion

A combined view of quantitative and qualitative results allows us to conclude with the following assessments regarding our three hypotheses. First, as quantitative, static, and time-sensitive analyses have shown, the news production of RT was generally aligned to public discourse and followed the trend lines observed for mainstream news media (H1). However, we could also observe RT’s outstanding activity in a number of international affairs-related topics, including Brexit and EU Politics. These findings clearly stand out as exceptions due to their unusually high activity.

As suggested above, we have mixed support for hypothesis 2. RT news outlets were indeed active in covering divisive issues for national publics that were likely to produce affective reactions, such as criminal offenses and political scandals or, most notably for the French case, the yellow vest protest movements. Nevertheless, the RT outlets’ preoccupation with topics related to international affairs runs counter to this assumption as those topics cannot be seen as divisive issues and can be considered unlikely to have produced affective reactions in larger audiences.

Finally, given the dominance of international affairs related topics in the RT news corpora with articles that strongly differ from common framing in established mainstream newspapers, we cannot lend outright support to hypothesis 3. For these main fields of RT activity, we see how authors seek to introduce alternative interpretations and frames, such as alternative ways of meaning-making with respect to major international crises, great power rivalry and especially the opposition between the United States and Russia. While the latter is hardly surprising given the fact that RT outlets are state-sponsored media operating in foreign countries to improve or correct the image of Russia, this effect has become clearer through our analysis unearthing the unique dominance of these topics and their one-sided framing. One should note, however, that similar observations could not be made for the other topic-related corpora. Instead, for the other subcorpora of relevance for RT – crime and political scandals, the yellow vest protest movement and European politics – we can mostly observe a similarity in framing with at least one of the mainstream outlets (with the notable exception of Brexit-related news).

All in all, our findings show a diversified approach of strategic communication for RT news outlets. While RT outlets broadly orient their news coverage toward national public discourse, they aim to set a particular tone in a number of strategically selected topics. While the first observation is in line with our expectations based on the sociology of knowledge, the latter implies a strategic motivation behind their engagement that is less dependent on the domestic discursive contexts. However, this matches the strategic role that is ascribed to RT in previous research. Covering relevant topics and taking up common discursive patterns for most of them might be a prerequisite for entering a national news market and attracting audiences therein. Adjusting to the nationally structured stocks of knowledge would then be a precondition for presenting alternative meaning-making for selected topics of strategic importance. Thus, following the beaten track of public discourse might generally put media actors like RT in a position to gain the reach and “credibility” needed as a news outlet to spread alternative frames and narratives and counter the mainstream discourse. In our study, these alternative frames were particularly visible in the depiction of international affairs, supporting and legitimizing Russian foreign policy.

Our paper not only makes a theoretical contribution to the ongoing scholarly debates on information operations that could bridge the gap between macro-oriented problem definitions and micro- and meso-level-oriented empirical evidence. It also bridges the scholarly discussions in political communication and international relations by introducing a new interdisciplinary perspective. Thus, it contributes to a more differentiated assessment of foreign information operations that may otherwise trigger a “moral panic” about disinformation at large and its alleged effects on democracy (Jungherr & Schroeder, 2021). Moreover, with our empirical observations, we give novel insights from a comparative study of news streams in Germany and France and present a multi-method approach combining topic modeling with qualitative analysis. While we would assess the methodological combination positively as it produced interpretable and insightful results, we also want to point to the limitations when applying topic modeling in social science research and especially comparative analyses. Topics as bag of words models produced by STM need to be treated with a grain of caution regarding their interpretability, especially when it comes to comparative analysis between different corpora and national contexts. We addressed this problem by exerting qualitative analyses and evaluating our findings at various stages. However, further developments in methodological research are needed to make such combined approaches more robust and adapt them to the needs of comparative research. Another limitation is that our sample does not fully represent the mainstream media sphere in our selected countries. We focused our analysis on news outlets that we expected to represent a potential overlap with RT’s audience, which would allow the latter to gain traction within the national discourse.

With RT having been removed from the media market in Western European countries in reaction to the Russian war against Ukraine, our findings maintain a retrospective value. While possibilities for generalizations are always limited, they appear even more reduced in face of the brutality with which Russian geopolitical goals have come to light in the beginning of 2022. We would however argue that, given the diverse hybrid media environment we live in, the relative openness of democratic societies, and the expected increase in the intensity of international conflict, our study provides valuable insights that can be built upon both when studying ongoing information operations at the international scene and when reflecting upon the vulnerabilities and resilience mechanisms of democratic societies.

References

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211 – 236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Allcott, H., Gentzkow, M., & Yu, C. (2019). Trends in the diffusion of misinformation on social media. Research & Politics, 6(2), 1 – 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168019848554

Anderson, C. W. (2021). Fake News is Not a Virus: On Platforms and Their Effects. Communication Theory, 31(1), 42 – 61. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtaa008

Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122 – 139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317

Benoit, K., Watanabe, K., Wang, H., Nulty, P., Obeng, A., Müller, S., & Matsuo, A. (2018). Quanteda: An R package for the quantitative analysis of textual data. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(30), 774. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00774

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network Propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford University Press.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1991). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Penguin.

BILD. (2019, February 24). Blutiger Machtkampf an der Grenze zu Venezuela: Hoffnungsträger Guaido bringt erste Hilfslieferungen. BILD.

Block, T. (2019, March 23). Wie hält May den Brexit-Irrsinn aus? BILD. https://www.bild.de/politik/ausland/politik-ausland/unter-dauerbeschuss-wie-haelt-may-den-brexit-irrsinn-aus-60839238.bild.html

Bolzen, S. (2019, March 30). 50 Shades of No: Theresa Mays Deal scheitert ein weiteres Mal. WELT. https://www.welt.de/print/die_welt/article191076781/50-Shades-of-No-Theresa-Mays-Deal-scheitert-ein-weiteres-Mal.html

Cinelli, M., Conti, M., Finos, L., Grisolia, F., Kralj Novak, P., Peruzzi, A., Tesconi, M., Zollo, F., & Quattrociocchi, W. (2019). (Mis)Information Operations: An Integrated Perspective. Journal of Information Warfare, 18(2), 83 – 98.

Chadwick, A. (2013). The hybrid media system: Politics and power. Oxford University Press.

Collomp, F. (2019, May 27). L’Europe n’en a pas fini avec le Brexit. Le Figaro. https://www.lefigaro.fr/international/l-europe-n-en-a-pas-fini-avec-le-brexit-20190527

Couldry, N., & Hepp, A. (2017). The mediated construction of reality. Polity Press.

Dunn Cavelty, M. (2008). Cyber-security and threat politics: US efforts to secure the information age. Routledge.

Ellul, J. (1965). Propaganda. The Formation of Men’s Attitudes. Vintage Books.

Elswah, M., & Howard, P. N. (2020). “Anything that Causes Chaos”: The Organizational Behavior of Russia Today (RT). Journal of Communication, 70(5), 623 – 645. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa027

European Commission. (2018). A multi-dimensional approach to disinformation: Report of the independent high level group on fake news and online disinformation. Publications Office of the European Union.

European Parliament. (2019). Foreign electoral interference and disinformation in national and European democratic processes. European Parliament resolution of 10 October 2019 on foreign electoral interference and disinformation in national and European democratic processes (2019/2810(RSP)).

EU vs DISINFORMATION (2021). Vilifying Germany; Wooing Germany. Retrieved from https://euvsdisinfo.eu/villifying-germany-wooing-germany/

Farrell, H., & Schneier, B. (2018). Common-Knowledge Attacks on Democracy. Berkman Klein Center Research Publication, 2018(7). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3273111

Farrell, H., & Newman, A. L. (2021). The Janus Face of the Liberal International Information Order: When Global Institutions Are Self-Undermining. International Organization, 75(2), 333–358. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000302

Foucault, M. (2002). Archaeology of knowledge. Routledge.

FranceSoir. (2019, April 3). L’Otan a 70 ans: entre “menace russe” et hausse des dépenses militaires en Europe. France Soir. https://www.francesoir.fr/politique-monde/otan-70-ans-la-menace-russe-hausse-depenses-militaires-europe

FranceSoir. (2019, June 26). L’Union européenne se saisit de la 5G.

France Soir. https://www.francesoir.fr/politique-monde/lunion-europeenne-se-saisit-de-la-5g

Frischlich, L., & Humprecht, E. (2021). Trust, Democratic Resilience, and the Infodemic. Policy Paper Series by the Israel Public Policy Institute: “Facing up to the Infodemic: Promoting a Fact- Based Public Discourse in Times of Crisis”. Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

Gerrits, A. W. M., (2018). Disinformation in International Relations: How Important Is It? Security and Human Rights 29(1 – 4), 3 – 23. https://doi.org/10.1163/18750230-02901007

Goldsmith, J., & Russell, S. (2018). Strengths Become Vulnerabilities: How a digital world disadvantages the United States in its international relations. Aegis Series Paper, 1806, 1 – 22.

Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B., & Lazer, D. (2019). Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 US presidential election. Science, 363(6425), 374 – 378. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau2706

Guess, A., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2018). Selective Exposure to Misinformation: Evidence from the consumption of fake news during the 2016 US presidential campaign. European Research Council, 9(3), 1 – 14.

Horowitz, M., Cushion, S., Dragomir, M., Gutiérrez Manjón, S., & Pantti, M. (2021). A Framework for Assessing the Role of Public Service Media Organizations in Countering Disinformation. Digital Journalism, 10(5), 843 – 865. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1987948

Humprecht, E., Esser, F., & van Aelst, P. (2020). Resilience to Online Disinformation: A Framework for Cross-National Comparative Research. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(3), 493 – 516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219900126

Jamieson, K. H. (2018). Cyberwar: How Russian hackers and trolls helped elect a president; what we don’t, can’t, and do know. Oxford University Press.

Jungherr, A., & Schroeder, R. (2021). Disinformation and the Structural Transformations of the Public Arena: Addressing the Actual Challenges to Democracy. Social Media + Society, 7(1), 205630512198892. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305121988928

Käufer, T. (2019, February 24). Venezuela-Krise: Washingtons wütende Hilflosigkeit. WELT. https://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/article189332941/Venezuela-Krise-Washingtons-wuetende-Hilflosigkeit.html

Keim, K. (2019, May 8). Alen erstochen: Mutmaßlicher Täter hätte abgeschoben werden können. BILD. https://www.bild.de/bild-plus/regional/muenchen/muenchen-aktuell/alen-17-in-muenchen-erstochen-taeter-haette-abgeschoben-werden-koennen-61745708.bild.html

Keller, R. (2005). Analysing Discourse: an approach from the sociology of knowledge. Forum: Qualitative Social Research (FQS), 6(3), Art. 32.

Keller, R. (2013). Doing discourse research: An introduction for social scientists. SAGE Publications.

Kleine, R., Link, A., & Tiede, P. (2019, April 6). Staatsrechtler schlägt Alarm: Verhunzen die Brexit-Briten uns die Europa-Wahl?. BILD https://www.bild.de/bild-plus/politik/ausland/politik-ausland/staatsrechtler-schlaegt-alarm-verhunzen-die-brexit-briten-uns-die-europa-wahl-61071692,view=conversionToLogin.bild.html

Lanoszka, A. (2019). Disinformation in international politics. European Journal of International Security, 4(2), 227 – 248. https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2019.6

Lupia, A., & McCubbins, M. D. (1998). The democratic dilemma. Can citizens learn what they need to know?. Cambridge University Press.

Macdonald, S. (2006). Propaganda and Information Warfare in the Twenty-First Century: Altered Images and Deception Operations. Routledge.

Mannheim, K. (1964). Wissenssoziologie. Auswahl aus dem Werk. Soziologische Texte, 28. Luchterhand.

Maréchal, N. (2017). Networked Authoritarianism and the Geopolitics of Information: Understanding Russian Internet Policy. Media and Communication, 5(1), 29 – 41. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v5i1.808

Marwick, A., & Lewis, R. (2017). Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online. Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/pubs/oh/DataAndSociety_MediaManipulationAndDisinformationOnline.pdf

Omand, D. (2018). The threats from modern digital subversion and sedition. Journal of Cyber Policy, 3(1), 5 – 23. https://doi.org/10.1080/23738871.2018.1448097

Pomerantsev, P. (2014). How Putin Is Reinventing Warfare. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/05/05/how-putin-is-reinventing-warfare/

Rid, T. (2020). Active measures: The secret history of disinformation and political warfare. Profile Books.

Rives, F. (2019, February 24). Gilets jaunes et policiers, ennemis jurés… Vraiment ? (PHOTOS, VIDEOS). RT en Français. http://web.archive.org/web/20220307132727/https://francais.rt.com/france/59441-gilets-jaunes-policiers-ennemis-jures-vraiment

Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., & Tingley, D. (2016). Navigating the Local Modes of Big Data: The Case of Topic Models. In R. M. Alvarez (Ed.), Computational Social Science: Discovery and Prediction, 51 – 97. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316257340.004

Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., & Tingley, D. (2019). stm: An R Package for Structural Topic Models. Journal of Statistical Software, 91(1), 1 – 40. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v091.i02

RT Deutsch. (2019, April 30). Venezuela: Guaidós Putschversuch gescheitert RT Deutsch. http://web.archive.org/web/20190503030755/https://deutsch.rt.com/international/87674-putschversuch-in-venezuela-gescheitert/

RT Deutsch. (2019, May 3). Venezuela: Was sind die beiden Oppositionsführer Guaidó und López wert? RT Deutsch. http://web.archive.org/web/20210115221426/https://de.rt.com/amerika/87774-venezuela-was-sind-die-beiden-oppositionsfuehrer-guaido-lopez-wert/

RT Deutsch. (2019, June 21). US-Mauschelei um iranischen Abschuss der 170-Millionen-Drohne. RT Deutsch.

RT Deutsch. (2019, June 25). Iran: USA setzen auf Eskalation und versperren mit neuer Sanktionswelle Weg für diplomatische Lösung. RT Deutsch. http://web.archive.org/web/20220308045810/https://de.rt.com/der-nahe-osten/89534-iran-usa-setzen-auf-eskalation-versperren-dialog/

RT Deutsch. (2019, June 26). Brutale Gruppenvergewaltigungen in Düsseldorf und ein Prozessbeginn in Freiburg. RT Deutsch. http://web.archive.org/web/20220308042554/https://de.rt.com/inland/89568-brutale-gruppenvergewaltigung-in-dusseldorf-prozessbeginn/

RT en Français. (2019, April 25). Vladivostok: Poutine salue la politique de détente entamée par Kim Jong-un dans la péninsule. RT en Français. http://web.archive.org/web/20220307131824/https://francais.rt.com/international/61372-sommet-vladivostok-vladimir-poutine-salue-politique-detente-entamee-kim-jong-un

RT en Français. (2019, May 26). Le parti du Brexit en tête des élections européennes au Royaume-Uni. RT en Français. http://web.archive.org/web/20190527073205/https://francais.rt.com/international/62477-parti-brexit-tete-elections-europeennes-royaume-uni

RT en Français. (2019, May 26). Européennes: désaveu pour La République en marche et ses alliés. RT en Français. https://francais.rt.com/france/62460-europeennes-victorieux-republique-marche-ses-allies-creent-surprise

RT en Français (2019, June 5). A Moscou, Xi et Poutine célèbrent la lune de miel des relations russo-chinoises. RT en Français. http://web.archive.org/web/20220307131134/https://francais.rt.com/international/62732-a-moscou-xi-poutine-celebrent-lune-miel-relations-russo-chinoises

RT en Français. (2019, June 7). Poutine et Xi font front commun contre la domination américaine. RT en Français. http://web.archive.org/web/20190608135242/https://francais.rt.com/international/62820-vladimir-poutine-xi-xinping-affichent-front-commun-domination-washington

Scheler, M. (1960). Probleme einer Soziologie des Wissens. In M. Scheler (Ed.), Die Wissensformen und die Gesellschaft (Vol. 8, p. 536). Francke. (Original work published 1926).

Schippmann, A., & Bräuner, V. (2019, May 8). Krise zwischen den USA und dem Iran: Warum die Eskalation der Mullahs eine Gefahr für uns ist. BILD. https://www.bild.de/bild-plus/politik/ausland/politik-ausland/iran-und-die-usa-wie-gefaehrlich-wird-dieser-konflikt-fuer-die-welt-61761740,view=conversionToLogin.bild.html

Schünemann, W. J. (2014). Subversive Souveräne: Vergleichende Diskursanalyse der gescheiterten Referenden im europäischen Verfassungsprozess. Theorie und Praxis der Diskursforschung. Springer VS.

Schünemann, W. J. (2022). A threat to democracies? An overview of theoretical approaches and empirical measurements for studying the effects of disinformation. In M. D. Cavelty & A. Wenger (Eds.), Cyber Security Politics: Socio-technological transformations and political fragmentation (pp. 32 – 47). Routledge.

Shackelford, S., Schneier, B., Sulmeyer, M., Boustead, A., Buchanan, B., Craig, A., Herr, T., & Malekos Smith, J. Zhanna. (2016). Making Democracy Harder to Hack: Should Elections Be Classified as ‘Critical Infrastructure?’. University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, 50(3), 629 – 668. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2852461

Singer, P. W., & Brooking, E. T. (2018). LikeWar. The Weaponization of Social Media. Mariner.

Ungar, G. E. (2019, June 18). Nächste Runde der Eurokrise: Italien will mit Parallelwährung Würgegriff der Austerität entkommen. RT Deutsch. http://web.archive.org/web/20220308042117/https://de.rt.com/meinung/89280-naechste-runde-der-eurokrise-italien-will-mit-parallelwaehrung-wuergegriff-der-austeritat-entkommen/

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146 – 1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Vries, E. de, Schoonvelde, M., & Schumacher, G. (2018). No Longer Lost in Translation: Evidence that Google Translate Works for Comparative Bag-of-Words Text Applications. Political Analysis, 26(4), 417 – 430. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.26

WELT. (2019, June 17). Wollte Iran US-Drohnen vom Himmel holen? WELT. https://www.welt.de/print/welt_kompakt/print_politik/article195383545/Wollte-Iran-US-Drohnen-vom-Himmel-holen.html

Wickham, H. (2010). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (3rd ed.). Springer.

Yablokov, I. (2015). Conspiracy Theories as a Russian Public Diplomacy Tool: The Case of Russia Today (RT). Politics, 35(3-4), 301 – 315. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.12097

Date received: September 2021

Date accepted: August 2022

7 Appendix

7.1 Appendix A: Topic Modelling Statistics

Appendix A-I: Diagnostic Values of the Structural Topic Models for the German Case with k = 5 to k = 25

Appendix A-II: Diagnostic Values of the Structural Topic Models for the French Case with k = 5 to k = 25

7.2 Appendix B-I: Absolute Topic Proportions for the German Case

Figure 1: Absolute cumulative topic proportions by outlet in the German corpus

7.3 Appendix B-II: Absolute Topic Proportions for the French Case

Figure 2: Absolute cumulative topic proportions by outlet in the French corpus

7.4 Appendix C-I: Regression statistics of Topical Prevalence over outlet and day for the German Case

The regression utilizes the STM package’s estimateEffects() function. The variable ‘day’ is splined with the STM package’s splining function and 10 degrees of freedom. Reference for the ‘source’ (outlet) variable is the outlet “Die Welt”.

Topic 1 Financial & Business News

|

Term |

estimate |

std.error |

t value |

p.value |

|

|

(Intercept) |

0.110337 |

0.033907 |

3.254108 |

0.001143 |

** |

|

stm::s(day)1 |

0.084919 |

0.064989 |

1.306668 |

0.191367 |

|

|

stm::s(day)2 |

0.022115 |

0.036948 |

0.598539 |

0.549499 |

|

|

stm::s(day)3 |

0.043501 |

0.047420 |

0.917344 |

0.358992 |

|

|

stm::s(day)4 |

0.067981 |

0.041288 |

1.646495 |

0.099705 |

. |

|

stm::s(day)5 |

0.042909 |

0.047428 |

0.904718 |

0.365645 |

|

|

stm::s(day)6 |

0.033003 |

0.041092 |

0.803158 |

0.42191 |

|

|

stm::s(day)7 |

0.016003 |

0.045069 |

0.355066 |

0.72255 |

|

|

stm::s(day)8 |

0.052165 |

0.049987 |

1.043561 |

0.296723 |

|

|

stm::s(day)9 |

0.029901 |

0.050330 |

0.594087 |

0.552472 |

|

|

stm::s(day)10 |

0.054559 |

0.052085 |

1.047490 |

0.294908 |

|

|

sourceBild |

0.009801 |

0.060823 |

0.161140 |

0.871987 |

|

|

sourceRT Deutsch |

-0.008540 |

0.049455 |

-0.172692 |

0.862899 |

|

|

stm::s(day)1:sourceBild |

-0.143853 |

0.117291 |

-1.226469 |

0.220062 |

|

|

stm::s(day)2:sourceBild |

-0.038212 |

0.075637 |

-0.505200 |

0.613433 |

|

|

stm::s(day)3:sourceBild |

-0.111734 |

0.086715 |

-1.288524 |

0.197605 |

|

|

stm::s(day)4:sourceBild |

-0.064440 |

0.076261 |

-0.844995 |

0.398141 |

|

|

stm::s(day)5:sourceBild |

-0.064107 |

0.081936 |

-0.782411 |

0.433998 |

|

|

stm::s(day)6:sourceBild |

-0.116449 |

0.074892 |

-1.554889 |

0.120016 |

|

|

stm::s(day)7:sourceBild |

-0.070524 |

0.082124 |

-0.858750 |

0.390507 |

|

|

stm::s(day)8:sourceBild |

-0.106118 |

0.087633 |

-1.210930 |

0.225961 |

|

|

stm::s(day)9:sourceBild |

-0.083841 |

0.091241 |

-0.918895 |

0.358181 |

|

|

stm::s(day)10:sourceBild |

-0.089672 |

0.078814 |

-1.137758 |

0.255259 |

|

|

stm::s(day)1:sourceRT Deutsch |

-0.179007 |

0.089572 |

-1.998471 |

0.045703 |

* |

|

stm::s(day)2:sourceRT Deutsch |

-0.047965 |

0.055020 |

-0.871777 |

0.383359 |

|

|

stm::s(day)3:sourceRT Deutsch |

-0.085690 |

0.065864 |

-1.301004 |

0.193298 |

|

|

stm::s(day)4:sourceRT Deutsch |

-0.134371 |

0.060474 |

-2.221949 |

0.026317 |

* |

|

stm::s(day)5:sourceRT Deutsch |

-0.036700 |

0.065039 |

-0.564272 |

0.572587 |

|

|

stm::s(day)6:sourceRT Deutsch |

-0.113400 |

0.062959 |

-1.801192 |

0.071714 |

. |

|

stm::s(day)7:sourceRT Deutsch |

-0.043866 |

0.063972 |

-0.685707 |

0.492919 |

|

|

stm::s(day)8:sourceRT Deutsch |

-0.114602 |

0.076473 |

-1.498600 |

0.134021 |

|

|

stm::s(day)9:sourceRT Deutsch |

-0.074553 |

0.068331 |

-1.091062 |

0.275281 |

|

|

stm::s(day)10:sourceRT Deutsch |

-0.100103 |

0.072480 |

-1.381101 |

0.16729 |

|

|

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1 |

|||||

Topic 2 Real Life Stories & Celebrity News

|

Term |

estimate |

std.error |

t value |

p.value |

|

|

(Intercept) |

0.069055 |

0.025186 |

2.741789 |

0.006125 |

** |

|

stm::s(day)1 |

-0.037192 |

0.046039 |

-0.807839 |

0.41921 |

|

|

stm::s(day)2 |

0.009097 |

0.030411 |

0.299144 |

0.764838 |

|

|

stm::s(day)3 |

-0.023143 |

0.033900 |

-0.682674 |

0.494835 |

|

|

stm::s(day)4 |

-0.008445 |

0.031255 |

-0.270210 |

0.787006 |

|

|

stm::s(day)5 |

0.018536 |

0.031486 |

0.588720 |

0.556067 |

|

|

stm::s(day)6 |

-0.015141 |

0.030421 |

-0.497705 |

0.618707 |

|

|

stm::s(day)7 |

-0.018095 |

0.032336 |

-0.559603 |

0.575768 |

|

|

stm::s(day)8 |

-0.000876 |

0.035116 |

-0.024954 |

0.980093 |

|

|

stm::s(day)9 |

-0.010414 |

0.038405 |

-0.271159 |

0.786277 |

|

|

stm::s(day)10 |

-0.002523 |

0.037398 |

-0.067470 |

0.94621 |

|

|

sourceBild |

0.216275 |

0.054603 |

3.960854 |

7.5e-05 |

*** |

|

sourceRT Deutsch |

-0.051384 |

0.035733 |

-1.437993 |

0.150479 |

|

|

stm::s(day)1:sourceBild |

0.196982 |

0.105921 |

1.859717 |

0.062966 |

. |

|

stm::s(day)2:sourceBild |

0.015167 |

0.065319 |

0.232198 |

0.81639 |

|

|

stm::s(day)3:sourceBild |

0.108926 |

0.083380 |

1.306375 |

0.191466 |

|

|

stm::s(day)4:sourceBild |