The Emergence of Platform Regulation in the UK

An Empirical-Legal Study

1 Introduction: Platforms as an emerging regulatory object

Platforms are everywhere. They keep us connected, make markets, entertain, and shape public opinion. A worldwide pandemic without this digital infrastructure would have unfolded quite differently. Still, the technological optimism that inflected the early years of the Internet is disappearing fast. Giant digital firms are now seen as unaccountable multinational powers. They survey our private sphere and accumulate data, they dominate commerce, they mislead publics, and evade democratic control.

This deep societal discontent has been reflected in new terms, such as “fake news,” “online harms,” “dark patterns,” “predatory acquisition,” or “algorithmic discrimination.” It has been argued that the scale tipped from “tech-optimism” to “tech-lash” already in 2013 (Wooldridge 2013). In France, GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon) had become an acronym for American cultural imperialism by 2014 (Chibber 2014). Since 2016, a flurry of policy initiatives has focused on digital platforms as a regulatory object of a novel kind. This is a global trend, with reports and interventions in major jurisdictions that compete in shaping a new regulatory regime. 2 It is also spawning an academic subdiscipline of platform governance, investigating the legal, economic, social, and material structures of online ordering (Gillespie 2018; Van Dijck et al. 2018; Flew et al. 2019; Gorwa 2019a/b; Suzor 2019; Zuboff 2019).

Given that everybody is talking about platforms, it is unsettling that there is no accepted definition, certainly none that is sufficiently stable to guide a regulatory regime. Policy discourse mostly points to just a handful of US companies. What then are platforms, this new class of regulatory objects? The concept of digital intermediaries is nothing new, with an established jurisprudence on intermediary liability developed since the mid-1990s derived from a definition of internet services. 3 Broadcasting and press publishing regulators have an understanding of communication that may also apply to internet media (Napoli 2019). Competition regulators rely on the concept of dominance in specific markets (Moore and Tambini 2018; 2022). These regulatory regimes all extend to tech companies that undertake relevant activities. The emergence of the new regulatory object of “platforms” therefore requires explanation. In what respects is a platform different from an internet intermediary, a new media company, a dominant digital firm? What social forces shape the emerging regulatory field of platform governance – one that is cluttered with competing definitions, agencies, and interventions?

Here we offer a novel empirical perspective focusing on one specific country: the United Kingdom (UK). In the post-Brexit environment, the UK has sought to position itself as a state with global “convening power” (House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee 2020; Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport 2021), seeking to shape technological and regulatory standards.

Using a primary dataset of eight official reports issued by the UK government, parliamentary committees, and regulatory agencies during an 18-month period (September 2018 to February 2020, selection detailed in section 2 on methodology), we conducted a structural analysis of the emergence of the regulatory field of platform governance. Through content coding of these documents, we identified over 80 distinct online harms to which regulation has been asked to respond; we identified eight subject domains of law referred to in the reports (data protection and privacy, competition, education, media and broadcasting, consumer protection, tax law and financial regulation, intellectual property (IP) law, security law); we coded nine agencies mentioned in the reports for their statutory and accountability status in law, and identified their centrality in how the regulatory network is conceived in official discourse (Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), British Board of Film Classification (BBFC), Competition and Market Authority (CMA), Ofcom, Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), Intellectual Property Office (IPO), Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (CDEI), Internet Watch Foundation (IWF), Counter-Terrorism Internet Referral Unit (CTIRU)); we assessed their current regulatory powers (advisory, investigatory, enforcement) and identified the regulatory tools ascribed in the reports to these agencies, and potentially imposed by agencies on their objects (such as “transparency obligations,” “manager liability,” “duty of care,” “codes of practice,” “codes of conduct,” “complaint procedures”). Lastly, we quantified the number of mentions of platform companies in the reports, and focus attention on the key agencies involved.

In related work, drawing on Bourdieu’s analysis, we have suggested that the world of regulatory agencies is constituting a distinctive relational space –usefully described as a “regulatory field” (Schlesinger 2020: 1557–1558). The idea of a regulatory field is an application of Bourdieu’s term at first developed conceptually in relation to the way in which various forms of cultural life were structured. Accordingly, “a field is a separate social universe having its own laws of functioning independent of those of politics and the economy,” seen as “an autonomous universe endowed with specific principles of evaluation of practices and works.” This has “its specific laws of functioning within the field of power” (Bourdieu 1993: 162–164).

The regulatory field cannot escape the shaping forces of politics and economics within and between states, even where claims are made for autonomy within a given political order. For our study, the regulatory field includes, but is not exhausted by, the operations of, competences and relations between, agencies tasked to regulate platforms. Because the field of platform-regulatory power ranges from seeking to define the scope of competition in the economy to matters of politics and morals, it is intricately connected to the state, in particular the government of the day and the parliamentary committees to which regulators are also accountable. The set of relations maintained by regulators with the political world does not exhaust the range of relations that constitute the regulatory field. That is because apart from the regulatory bodies themselves, the regulatory field structures relations between the regulators and a wide range of stakeholders: these include the platforms that are being regulated; specialist and other lobbies pursuing a range of interests related to the practice of regulation; expert circles of professionals, academics, and think-tanks that routinely comment on, and seek to influence, regulatory policies; as well as the issue-focused engagement of a range of both systematically and sporadically engaged publics.

Developments in platform regulation in the UK demonstrate the specific range of activities encompassed and the ways in which these are parceled out between different regulators. The regulatory field, as noted, encompasses all of the diverse actors that enter into relations relevant to platform regulation. Within this wider set of relations, we may distinguish those relations that are specifically developed between regulatory bodies. This concerns action undertaken by those regulatory organizations that have been accorded a designated competence to undertake this task by the state. We are interested in the process of how this specific dimension of the regulatory field is being articulated. Between them, the regulators constitute a distinct and often fluctuating organizational field in which relations of competition and cooperation are continually negotiated.

Applying Bourdieu’s approach to organization theory, Emirbayer and Johnson (2008) have focused on the symbolic capital – the special authority – disposed of by major actors in a given field. The British approach to defining the regulatory scope of agencies is based on a division of labor within a field in which a subordinate form of power is exercised – or as Bourdieu terms it, a “dominated” form of power comes into play. This has a cultural dimension that both defines the scope of what each organization can undertake and the range of innovations that it engages in (Emirbayer and Johnson 2008: 14–16). This broad observation is highly relevant to the present study. As will be illustrated, the evolution of the regulatory field has meant that despite their distinctly defined remits, the particular agencies analyzed here have needed to develop cooperative strategies to address the lacunae built by design into the entire configuration of regulatory competences.

To put the British case in context, it should be noted that the emergence of online platforms as a regulatory object is part of a global phenomenon that has generated divergent national approaches. In its post-Brexit recalibration of geopolitics, the UK has been conceived as a nationally sovereign state that needs to defend its critical national infrastructure. Cybersecurity is an essential part of this approach and regulatory policy is likewise integral to policing the digital boundaries (Schlesinger 2022). The UK has taken to promoting its position as a convening power and exporter of norms under the declamatory slogan “Global Britain” (HM Government 2021).

Different national approaches are arguably in competition to establish what might become accepted standards – ways of dealing with the cross-border regulation of multinational tech giants. The UK is a particularly interesting reference point for comparative analysis. British law draws on a flexible common law tradition that has both facilitated international trade and enjoys a global language advantage. An analysis of the emergence of the regulatory field of platform regulation in the UK, it is contended, has potential implications for the wider study of the development of “regulatory webs,” “regulatory competition,” and other mechanisms of globalization (Braithwaite and Drahos 2000: 153, 550).

2 Methodology

A useful way of thinking about the formation of a new regulatory field is by considering what Downs (1972) labeled the “issue-attention” cycle. It takes time for a societal issue to emerge that requires attention. The process of defining a matter to be resolved is commonly accompanied by a rise in public policy and media attention as well as lobbying activity by relevant interests. Center-stage internationally are the growing and diverse attempts made by some governments to redress shifts of economic power, combat “online harms” and more generally to reconfigure regulatory scope as media and communication systems transform in the digital revolution. How to capture the objects, purposes, and means of regulation in a fast-moving technological environment is a key methodological challenge. We need to define what is within scope for observing the formation of a new regulatory field. We have taken one specific jurisdiction, that of the UK, as an instance of this process. This opens the way both to analyzing its particularities and to framing international comparative research.

To reveal the lineaments of the UK’s issue-attention cycle relating to platforms, we selected a sample of official reports published during an 18-month period between September 2018 and February 2020. An intense period of regulatory review had followed the 2017 general election. The governing Conservative Party’s election manifesto included a commitment to “make Britain the safest place in the world to be online” (Conservative and Unionist Party 2017: 77). During the same period, the UK Brexit negotiations were led by Conservative prime ministers: first, Theresa May, then Boris Johnson. Conservative policy increasingly became guided by a search for digital competitiveness under a regulatory framework that diverged from that of the EU 4.

Ofcom’s Discussion paper of September 2018, Addressing harmful online content, can be understood as the opening gambit in a game for regulatory authority. An intended future regulatory regime was finally set out in two government papers published in December 2020. This involved the establishment of a Digital Markets Unit under the aegis of competition regulator CMA, and the identification of communications regulator Ofcom as regulator of a new online “duty of care” 5. These were extensions of existing competences.

The key reports commissioned by a range of official actors both in anticipation of and seeking to influence these decisions were published during a period beginning in September 2018. Selected primary sources for analysis include two government-commissioned independent reports (Cairncross, Furman), a White Paper (Online harms), two parliamentary reports (DCMS Committee House of Commons, Communications Committee House of Lords), and three agency reports (Competition and Markets Authority, Ofcom, Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation). Our selection and characterization of these sources will be explained in more detail in the following section.

A wide range of political, economic, and social factors came into play. Economically, questions of competition were foregrounded. The stress on democracy and concern about “fake news” and disinformation also figured large and have increased in importance. Finally, there are social and moral concerns – worries about the negative aspects of social media uses, related abusive behaviors, and the vulnerability of young people and children to online dangers. Numerous issues related to a divided public culture, such as territorial politics, a range of inequalities in respect of race, ethnicity, gender, and class, and the emergent consequences of Brexit.

Our methodological approach captures how during the 18-month period under investigation, a desire for more policy intervention crystallized in the UK. The agenda derived from demands, alerts, alarms from government, a range of organized interests, and to some extent concern from the public. Within the issue-attention cycle identified, there was a mix of top-down and bottom-up defining of the problems. Interventions by government, parliament, and agencies acquired their own momentum. For parliament, the crisis of democracy – concern about political advertising, false news, violent extremism – has been one spur. In addition there have been external agenda-seeking activities that have been reflected in official papers, such as press publishers trying to find some redress for lost revenues as well as the impact of particular media “scandals.”

2.1 Reports used as primary sources

The primary sources that are at the heart of the issue-attention cycle discussed here include government-commissioned independent reports, a White Paper, two parliamentary committee reports, and three agency reports. Next, we provide a brief characterization, in chronological order, of each of the eight official reports selected for sociolegal content analysis.

1)Ofcom discussion paper: Addressing harmful online content: A perspective from broadcasting and on-demand standards regulation (September 18, 2018)

The purpose of this discussion paper was to shape the ongoing discussion on online content moderation, and to anticipate potential regulatory duties related to Ofcom’s expertise and capacity as an established communications regulator, especially in the broadcasting area. It discussed harms to people, not the economy, and gave prominence to illegal content, misleading political advertising, “fake news,” and child protection.

2)Cairncross Review (commissioned by the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS)): A sustainable future for journalism (February 12, 2019).

The Cairncross Review is an independent report prepared by Dame Frances Cairncross for the DCMS. It assessed the current and future market environment facing the press and high-quality journalism in the UK. It discussed media economics (in particular in relation to online advertising) and political issues (such as public-interest and fake news).

3)House of Commons DCMS Committee: Disinformation and “fake news” (February 18, 2019)

This Select Committee report resulted from a political inquiry prompted by the Cambridge Analytica scandal (among others) into uses of users’ data in the political and electoral context, particularly into how users’ political choices might be affected and influenced by online information. The inquiry and the report were prepared by the House of Commons DCMS Committee (chair: Damian Collins).

4)House of Lords Communications Committee: Regulating in a digital world (March 9, 2019)

A parliamentary report from the House of Lords Communications Committee’s inquiry into how regulation of the internet should be improved, focusing on the upper “user services” layer of the internet, with a focus on platforms. It distinguished three categories of harmful online content: illegal, harmful but not illegal, and antisocial.

5)Furman review (Treasury and Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS)): Unlocking digital competition (March 13, 2019)

A report prepared by a Digital Competition Expert Panel (set up by the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer). The panel was led by the Harvard economist Jason Furman (President Barack Obama’s chair of the Council of Economic Advisers) with input from competition and technology experts. The report examined the opportunities and challenges the digital economy may pose for competition policy. It considered the effects of a small number of big players in digital markets, including in the context of mergers.

6)Online Harms White Paper (DCMS & Home Office) (April 8, 2019)

A White Paper presented by two government departments, the DCMS and the Home Office, setting out proposals for future legislation. The White Paper sought to identify a comprehensive spectrum of online harms, and proposed a new regulatory framework for those harms. The aim of making the UK the safest place in the world to go online and grow digital business was articulated as the underlying rationale.

7)Competition and Markets Authority market study: Online platforms and digital advertising (interim report, December 18, 2019)

The report is the result of a formal market study into online platforms and digital advertising. It focused on search advertising, dominated by Google and display advertising, dominated by Facebook. The report aimed to understand the advertising-funded platforms’ business models and challenges they might pose. This was an interim report. It is conventional in competition inquiries to expose factual findings and potential recommendations to challenges in this form. The final report was published on July 3, 2020. 6

8)Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation: Review of online targeting (February 4, 2020)

The CDEI is an advisory body established within the DCMS. The report focused on the use of data in targeting and shaping users’ experience online. It investigated users’ attitudes toward online targeting, current regulatory mechanisms and solutions, and whether they could be made consistent with public values and law.

2.2 The steps taken

Following the identification of reports (the sample selection), seven sequential steps were initially taken in order to reveal the implicit definitions circumscribing an emerging regulatory field, and to clarify the key actors and forces shaping the field.

The analysis was conducted by reading and manually coding all eight reports. Applying orthodox content analysis techniques (Krippendorff 2018), pilot-coding categories were developed iteratively by all three researchers, and applied by one of the researchers. Unresolved coding was reviewed by all three researchers, acting as experts. This first round of coding produced quantitative data in spreadsheet form. A secondary analysis was then performed, drawing on material external to the reports. In summary form, the seven steps taken were to:

1)Identify problems that are stated as in need of solution (content analysis: “harms” as a proxy for emerging social issues).

2)Identify legal subject domains (content analysis: expert legal coding).

3)Identify agencies (content analysis: secondary research on scale and geography).

4)Identify centrality of agencies (cross-references to agencies between reports, permitting a network analysis).

5)Identify statutory basis and powers of agencies (expert legal coding, using secondary legal sources).

6)Identify regulatory tools (content analysis: expert legal coding).

7)Identify regulatory objects (content analysis: citation frequency of firms).

The results of the content analysis were presented to representatives of five key UK regulatory agencies at an event hosted on February 26, 2020 by the British Institute of International and Comparative Law in London (CREATe 2020). In line with our methodology, the presentation of results to insiders is an important check on those actors’ views. Consequent reflexive deliberation is a form of validation by those whose practices are being analyzed (Schlesinger et al. 2015).

The sample selection, which was presented as capturing one issue-attention cycle, was not challenged. Representatives of regulatory bodies accepted the expert coding applied as well as the portrayal represented by the quantitative results. At the same time, they commented in ways that offered important qualitative insights into the self-conceptions held by given agencies, as well as emphasizing the interconnectedness of relations between regulators that an exclusively external analysis could not have elicited. 7

3 Findings

In this section, we present the findings of the content analysis in tabular form, following the sequence of the seven-step method taken.

3.1 Online harms

In line with the issue-attention perspective, we begin by extracting a list of online issues that are considered to be problematic in the reports, and therefore as in need of a remedial response. We label these “harms.”

1)Ofcom discussion paper: Addressing harmful online content: A perspective from broadcasting and on-demand standards regulation [“HarmCont”] (September 18, 2018)

In the Ofcom discussion paper, 16 distinct harms are identified. These touch upon a broad spectrum of issues. While the main focus of the report is on societal harms, such as people’s exposure to harmful or age-inappropriate content, Ofcom also takes note of market concerns, security, and IP.

Table 1: List of harms identified in the Ofcom discussion paper

|

Report |

Harms |

|

HarmCont |

|

2)Cairncross Review (commissioned by DCMS): A sustainable future for Journalism (February 12, 2019)

The diagnosis of the Cairncross report focuses on the effects of search engines and news aggregation services on the press publishing market and identifies an unbalanced relationship between press publishers and platforms as a threat to sustainable quality journalism. Press publishers’ loss of advertising revenue is seen as contributing to disinformation and a decline in public-interest reporting.

Table 2: List of harms identified in the Cairncross Review

|

Report |

Harms |

|

Cairncross |

|

3)House of Commons DCMS Committee: Disinformation and “fake news” [“Disinfo”] (February 18, 2019)

The report prepared by the DCMS Committee has a political focus, with a particular emphasis on the electoral influence of platforms. It is concerned with the effects of digital campaigning and advertising on political discourse, with the distortion and aggravation of people’s views, and also extends to mental health issues. Market-related harms are mentioned in an ancillary manner.

Table 3: List of harms identified in the House of Commons DCMS Committee’s report

|

Report |

Harms |

|

Disinfo |

Harmful

Illegal

|

4)House of Lords Communications Committee: Regulating in a digital world [“RegDigiW”] (March 9, 2019)

The report distinguishes three categories of harmful online content: illegal, harmful but not illegal (which nevertheless is inappropriate, for example for children), and antisocial. Harms listed are mostly societal, such as child sexual abusive content and cyberbullying. The infringement of IP rights is mentioned as an economic harm.

Table 4: List of harms identified in the House of Lords Communications Committee’s report

|

Report |

Harms |

|

RegDigiW |

Harmful

Illegal

|

5)Furman review (Treasury and Department for BEIS): Unlocking digital competition (March 2019)

The report focuses on economic harms, stemming from the negative effects of a small number of big players on digital markets, including the abuse of dominant positions and anticompetitive behavior. Societal harms, such as users’ limited control over collection and management of their personal data, are also highlighted.

Table 5: List of harms identified in the Furman review

|

Report |

Harms |

|

Furman |

|

6)Online Harms White Paper [“OnHarm”] (DCMS & Home Office) (April 8, 2019)

The harms identified in the document focus on the activities harmful to individuals and society, not the economy or organizations. Harms are divided into three categories, according to the clarity of their definition. Prominent are activities harmful to children, such as child sexual exploitation and abuse, sexting, advocacy of self-harm, and access to pornography. Also noted are the spread of terrorist content and incitement to violence, as well as disinformation, and the sale of illegal goods.

Table 6: List of harms identified in the Online Harms White Paper

|

Report |

Harms |

|

OnHarm |

Harms with a clear definition

Harms with a less clear definition

Underage exposure to legal content

|

7)Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) market study: Online platforms and digital advertising [“DigiAd”] (interim report, 18 December 2019)

The report includes a consumer-focused list of harms (data extraction and encouraging consumers to share too much data), as well as harms stemming from platforms’ dominant positions in the market, such as a change of core services without notice, and restrictions on the interoperability of services.

Table 7: List of harms identified in the CMA market study

|

Report |

Harms |

|

DigiAd |

|

8)Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation: Review of online targeting [“OnTarg”] (February 4, 2020)

The report distinguishes harmful and illegal behavior. Listed harms concern individuals, not organizations, and include harms affecting children, such as sexual abuse and exploitation, as well as disinformation, polarization and bias in content recommendation, and unlawful discrimination.

Table 8: List of harms identified in the CDEI review

|

Report |

Harms |

|

OnTarg |

Harmful

Illegal

|

In total, over 80 distinct harms are identifiable across the reports analyzed. While there are broad overlaps relating to child protection, security and misinformation, the harms are articulated quite differently depending on the specific configurations of political, economic, or societal concerns that have shaped each document. In particular, the regulatory agenda was evidently driven by growing disquiet that has been crystallized in an ever-widening list of lawful but socially undesirable activities.

3.2 Legal subject domains

The previous section presented the range of issues (articulated as harms) perceived as in need of regulatory attention. We now turn to proposed solutions. The next step of our analysis was to identify and code the legal subject domains mentioned in the eight reports. Our assumption is that by mentioning a body of existing law, the drafters of a report expect that specific (existing or new) legal provisions in the subject area will offer solutions to the problem identified. Coding was based on the qualitative judgments of a legal expert. If in doubt, coding was reviewed by the research team as a whole. In most cases, the decision was straightforward. For example, when a specific domain of law or statute was directly cited, such as the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) this would be coded under “data protection and privacy.” Some areas of law are less clearly defined, and rely on multiple legal provisions. Such is the case with media literacy. The decision to code media literacy under “education” was motivated by the context in which it was mentioned: the education of pupils and improvement of school curriculum. Following an iterative process, we settled on eight domains that offered a degree of coherent jurisprudence in the UK context. These are: (i) data protection and privacy; (ii) competition law; (iii) education law; (iv) media and broadcasting law; (v) consumer protection law; (vi) tax law and financial regulation; (vii) IP law; and (viii) security law.

Table 9 shows where these subject domains are represented in the sampled reports.

Table 9: Subject domains represented across eight official reports

|

HarmCont |

Cairncross |

Disinfo |

Reg DigiW |

Furman |

On Harm |

DigiAd |

OnTarg |

|

|

Data protection and privacy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Competition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education (media literacy) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Media and broadcasting |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Consumer protection |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Tax law and financial regulation |

|

|

||||||

|

IP/copyright |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Security |

|

|

|

It should be noted that these domains of law are conceptually distinct, with very different traditions and underlying principles. Some are private law provisions that regulate behavior between individuals or firms (IP rights are such private rights). Others are public law provisions that involve the relationship between the state and individuals (such as tax law). And some are both public and private. For example, certain competition law provisions are enforced by the state, others can be pursued as private actions. For some subject areas, the sources of law are in common law jurisprudence; for others, sources are recent EU law. 8

The domains of law can also be distinguished by their underlying rationales, be they economic, social, or fundamental rights based. Are the underlying principles commensurable? Or do choices have to be made? 9 For the purposes of this article, it is revealing that data and competition solutions have been foregrounded. No proposed intervention evades these domains of law. The consumer law perspective is comparatively weak, as are interventions through the fiscal system. Security interventions lack explicit articulation.

3.3 Regulatory agencies

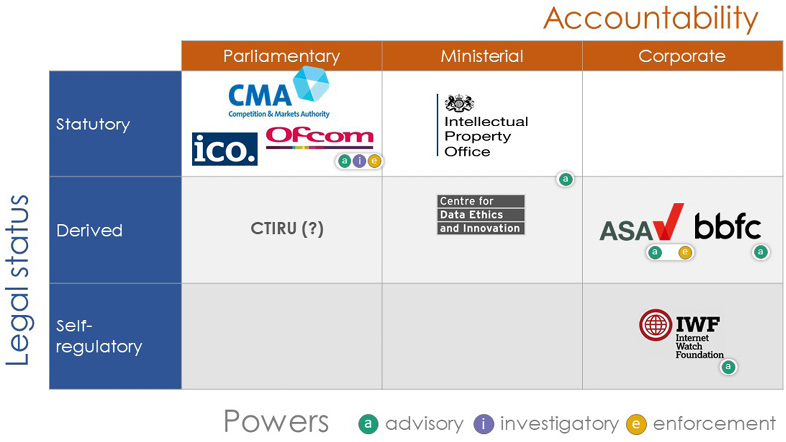

We now turn to the regulatory actors. Four pieces of analysis were performed. The first was a straightforward content analysis of the reports, with yes/no coding for each actor. Was a regulator or agency mentioned? The nine most-mentioned agencies were then selected for geographical and institutional profiling. In a third step, cross-references of all mentions of these agencies across the reports were coded in order to identify the centrality of a regulator in the network. Finally, the legal status, accountability, and regulatory powers (advisory, investigatory, enforcement) of each regulatory agency was assessed.

Table 10: The nine most prominent agencies (in alphabetical order)

|

Logo |

Agency |

|

ASA: Advertising Standards Authority The ASA is an independent UK regulator of advertising, established in 1962. It is funded by a voluntary levy on the advertising space paid for by the industry. The ASA sets standards for broadcast and non-broadcast advertising in the UK Code of Non-broadcast Advertising, Sales Promotion and Direct Marketing (CAP Code) and the UK Code of Broadcast Advertising (BCAP Code), and provides guidelines on their application. |

|

BBFC: British Board for Film Classification The BBFC is a film and video classification body. It issues classification certificates to audiovisual works distributed in the UK, pursuant to its classification guidelines. Films distributed in the UK need to be classified by the BBFC. The BBFC was founded by the industry in 1912 as the British Board of Film Censors. Its scope has grown considerably since the 1980s. |

|

CDEI: Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation CDEI is an expert committee of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), currently in its pre-statutory phase. It was set up in 2019 to provide the government with access to independent, impartial, and expert advice on the ethical and innovative deployment of data and artificial intelligence (AI). Together with its advisory role, CDEI seeks to analyze and anticipate risks and opportunities for strengthening ethical and innovative uses of data and AI, and to agree and articulate best practice for the responsible use of data and AI. |

|

CMA: Competition and Markets Authority The CMA is the UK competition regulator, a designated national competition authority. It was founded in 2013, and took over the roles of the Competition Commission and the Office of Fair Trading. The CMA is responsible, among others, for investigating mergers, conducting market studies, and making inquiries into anticompetitive behavior. The CMA seeks to promote competition, both within and outside the UK, for the benefit of consumers. |

|

CTIRU: Counter-Terrorism Internet Referral Unit CTIRU is formally a part of the Metropolitan Police Service. CTIRU’s aim is to work globally in cooperation with industry and private sector companies to remove illegal online content that breaches the UK’s terrorism provisions. CTIRU issues notices requesting removal of content which is in breach of websites’ terms of service. Public information on CTIRU is very limited, due to its national security status. |

|

|

ICO: Information Commissioner’s Office The Information Commissioner’s Office is an independent body. The Commissioner is an official appointed by the Crown, set up to uphold information rights and safeguard individuals’ privacy. The ICO deals with the Data Protection Act 2018 (which implements the EU General Data Protection Regulation). |

|

IPO: Intellectual Property Office Formerly the UK Patent Office, the IPO is responsible for IP rights in the UK, including patents, designs, trademarks, and copyright. The IPO is an executive agency of the Department for BEIS. |

|

IWF: Internet Watch Foundation The IWF is an independent, self-regulatory body working toward the goal of eliminating child sexual content abuse online. It prepares Uniform Resource Locator lists of webpages with child sexual abuse images and videos, and sends take-down notifications to hosting companies. The IWF actively searches for abusive content online and provides a hotline for the reporting of abusive content. |

|

Ofcom: Office of Communications Ofcom is the UK communications regulator. It regulates the TV, radio, and video on-demand sectors, fixed line telecoms, mobiles, postal services, and the airwaves over which wireless devices operate. |

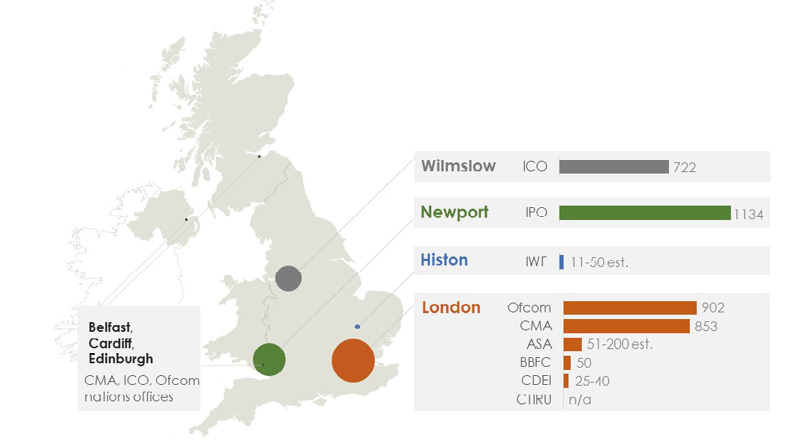

Looking at the geographical profile and labor force of these agencies, it is evident that regulatory power is London-centric in location, with a minor presence in the UK’s devolved nations (Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland). The IPO is an outlier. Almost all the IPO’s employees deal with the administration of registered rights (patents, trademarks, designs) out of its office in Newport in south Wales rather than considering regulatory issues. It is noteworthy that no public details about the labor force of the CTIRU are available. In total, fewer than 3000 staff are employed in regulatory agencies that we have identified as broadly relating to platforms. The resources required to install a functioning governance system to address the wide scope of platform activities will be considerable. 10

Table 11: Nine most cited regulatory agencies across eight official reports. Bottom row lists other agencies mentioned

|

Harm Cont |

Cairn cross |

Disinfo |

Reg DigiW |

Furman |

On Harm |

DigiAd |

OnTarg |

|

|

Ofcom |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CMA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ICO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ASA |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

CDEI |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

BBFC |

|

|

|

|||||

|

IPO |

|

|

||||||

|

IWF |

|

|

||||||

|

CTIRU |

|

|||||||

|

Other |

IMPRESS, IPSO |

Electoral Comm. |

FCA, Gambling Comm., IMPRESS, DMC, IPSO, PSA, PRA |

FCA, PSR |

Gambling Comm., Electoral Comm., EHRC |

FCA, Gambling Comm., Electoral Comm., EHRC |

Figure 1: Geographical and labor profile of the agencies. Size of circle corresponds to bar (n = number of employees)

Having identified the regulatory players in the emerging field and their network centrality, we coded their statutory basis, accountability, and powers. This was done through doctrinal (legal expert) analysis, based on secondary legal sources. The approach has enabled us to visualize the functions of regulatory agencies by reference to key dimensions of the UK’s political system, resulting in a taxonomy of regulators. This reflects the fluid British system of government, which lacks a formal written constitution. Executive regulatory powers can (sometimes) be created at the stroke of a minister’s pen. This contrasts with the more formal civil law traditions of continental Europe, where administrative law is prominent, and there may be less executive discretion.

Figure 2: Regulatory agencies by legal status, accountability, power

Three UK regulators (Ofcom, the CMA, and the ICO) have a secure statutory basis, report to the Westminster parliament, and exercise enforcement powers. As we have seen, each also has a considerable labor force (Ofcom: 902; CMA: 853; ICO: 722) and multidisciplinary expertise. Our analysis showed that these were the agencies consistently identified in official reports as those best equipped to be scaled up, and that is indeed what subsequently occurred. 11 In July 2020, the three agencies combined forces to create an informal alliance called the Digital Regulators Cooperation Forum, which has become the new fulcrum of regulatory effort (Schlesinger 2022).

Agencies that have evolved with a strong sectoral focus (film censorship, advertising standards) have an institutional set-up that is less in the public eye: the BBFC and the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) are funded by industry, but not quite self-regulatory (in the case of ASA its powers are derived from three different statutes). It will be interesting to see how their roles reconfigure in the context of growing platform regulation. For example, the ASA has started to issue guidance with respect to online influencers (ASA 2020).

The regulation of AI is likely to become more prominent. The CDEI is a recent arrival on the regulatory scene (25–40 staff). The government has committed itself to provide CDEI with statutory footing following its current pre-statutory phase (CDEI 2019).

The role of the IPO, an executive agency of the Department for BEIS, operates separately from other forms of platform regulation: it lacks distinct investigatory and enforcement powers. This is despite the fact that copyright-related content moderation from online platforms accounts for most take-down actions. 12 By its own account, the IPO is not a regulator.

There is very little public information on the legal–institutional set-up and operations of the CTIRU. This appears to be an executive unit without any clear statutory legitimacy. We do know that CTIRU is a part of the Metropolitan Police Service (“the Met”), a territorial police unit responsible for law enforcement in the London boroughs but at times exercising a wider remit. CTIRU was created in 2010 by an administrative (rather than a legislative) act. Formally, CTIRU as part of the Met might be accountable to the same body as the Met. According to the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011, the Met’s Commissioner is, in practice, appointed by the Home Secretary, who must take into account any recommendations from the Mayor of London. Although the Commissioner is accountable to the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime, terrorism is a matter of UK national security. The Commissioner reports to the Home Secretary on those matters where the force has national responsibilities. 13 The Security Service, MI5, which deals with counter-terrorism policy and legislation, also comes under the statutory authority of the Home Secretary. Its role is defined under the Security Service Act 1989. Among other activities, MI5 counters terrorism and cyber threats, gathers information on communications data, “information about communications, such as ‘how and when’ they were made, which is usually obtained from communications service providers” (Security Service 2022).

The Open Rights Group has shed some light on the workings of CTIRU. 14 First, CTIRU compiles a blacklist of overseas URLs, the hosting and distribution of which has given rise to criminal liability under the provisions of the Terrorism Act 2006. The list, managed by the Home Office, is provided to companies which supply filtering and firewall products to the public sector, which includes schools and libraries. As of 2016, schools and organizations that provide care for children under the age of 18 in the UK are obliged to restrict access to the URLs included on the CTIRU list, pursuant to their Prevent duty. This duty, imposed by the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015, requires schools and early education establishments to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism (Home Office 2015). There is no formal appeal process in the event of an URL being included on the blacklist.

Second, CTIRU operates a notification regime. It notifies platforms that they are hosting illegal content, issues requests to review according to their terms of service (ToS), and eventually pursues content removal. From examples of take-down requests made available via the Lumen database it seems that CTIRU assesses the illegality of content on the basis of UK terrorism legislation (the Terrorism Acts 2000 and 2006). 15 The notification regime operates without any explicit legal basis, and CTIRU sees it as voluntary. However, a detailed notification filed by CTIRU can strip a platform of the liability protection provided by the eCommerce Directive (Directive 2000/31/EC), as it provides the platform with actual knowledge of potentially illegal content.

CTIRU appears to have something close to an unaccountable censorship role. There are statutory reference points, but there is weak parliamentary accountability. CTIRU is anomalous within our taxonomy and appears to have emerged out of informal cooperation between the Met and the Security Service. It is therefore formally coded as self-regulatory (which it cannot be in practice, given both bodies’ accountability to the Home Secretary). This wide discretionary role, and the lack of clarity about its lines of accountability, is an interesting finding in itself. 16

The IWF is also classified as a self-regulatory body but it enjoys an “executive privilege”: a report on child-abusing content made to the IWF is considered to be a report to the relevant authority (Crown Prosecution Service 2004). Additionally, the IWF is exempt from criminal responsibility when it deals with abusive content for the purposes of preventing, reporting, and investigating the abuse.

3.4 Regulatory tools

Having identified perceived issues (“harms”), domains of law and actors (their legal status and powers), the analysis now seeks to extract proposed solutions that take the form of specific regulatory tools. Some of these are new responses to digital challenges (such as blocking lists), some are well known (such as imposing fines or manager liability). Table 12 lists the tools identified in the sample of official reports. Note that Ofcom’s 2018 Discussion Paper (HarmCont) is an exception in this analysis. Ofcom’s document initiated the issue-attention cycle in September 2018 but carefully avoided making any concrete proposals that might have prejudiced its future regulatory role.

Table 12: Proposed regulatory tools by official report

|

Report |

Tools |

|

HarmCont |

|

|

Cairncross |

|

|

Disinfo |

|

|

RegDigiW |

|

|

Furman |

|

|

OnHarm |

|

|

DigiAd |

|

|

OnTarg |

|

The list of regulatory tools was extracted using expert legal coding, closely following the terminology employed in the documentary corpus. Within the scope of the present article, there is no room for a detailed discussion of the history, legal basis, and novelty of the proposed interventions. 17

As a general trend, we note that transparency obligations imposed on firms and, vice versa, information-gathering powers by regulatory actors receive plenty of attention. There is also a resurgence of a particularly British style of intervention: the use of codes of conduct or codes of practice that remain flexible and responsive, and hover on the border between self-regulation and state enforcement. These are themes that also surface in the parallel emergence of platform regulation at the EU level, with the Digital Markets Act (targeting “gatekeepers” most prone to unfair business practices) and the Digital Services Act (targeting “very large online platforms” that are considered systemic and must control their own risks). 18 While both the EU and the UK stress ex ante obligations that seek to anticipate and prevent future harm, the EU proposes quantitative indicators for platform companies to come within scope of new duties and remains vague about the application of codes of behavior (which are encouraged but not required). The UK, in contrast, appears to suggest more discretionary identification of platforms with strategic market status (with respect to digital markets) or high-risk status (with respect to online safety) and gives the regulators powers to implement codes of conduct or codes of practice in a more responsive manner.19

3.5 Regulatory objects

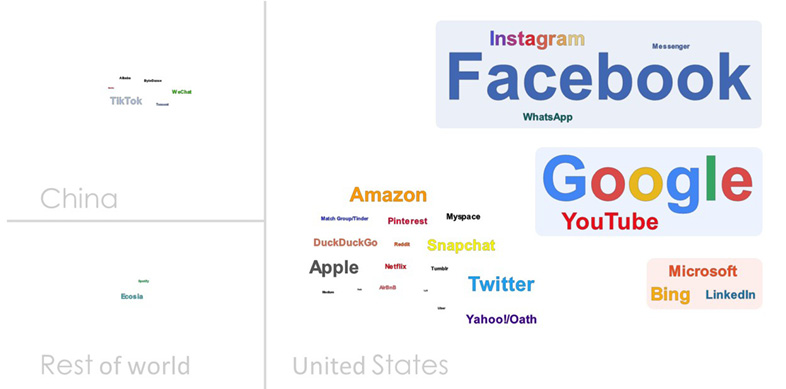

In this section, we report the results of simple frequency statistics derived from searching the eight reports in the sample for references made to given firms. We assume that any mention of a firm in the context of platform regulation will tell us something significant about the potential regulatory objects that have been identified as visible within the emerging field.

Figure 3 offers a word-cloud representation, with firms tagged by their national headquarters; 3320 (76%) of 4325 references to firms made in the reports are to just two US firms and their subsidiaries. Google (including YouTube) accounts for 1585 references; Facebook (including Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger) accounts for 1735 references. Only two platforms headquartered in Europe are mentioned (Spotify and Ecosia). Chinese firms are referenced 61 times. Not a single UK-headquartered firm figures.

Figure 3: Firm frequency citations by country headquarter in eight official reports

The regulatory landscape in the UK is being profoundly shaped in response to the perceived social and economic harms caused by the activities of just two multinational companies: Google and Facebook.

4 Conclusion

Our analysis of the emergence of the field of platform regulation in the UK has revealed a paradox of potentially wider application to other territories. States are worried about their sovereignty in the context of the power of big tech, and may end up delegating what are traditionally state regulatory powers to these platforms.

New obligations will be created, anticipating and preventing future harm (rather than in response to actual harm, which was the prevalent liability standard of the first phase of the Internet). In practice, these obligations will be enforced via the terms of service of platforms, and their content moderation policies.

The focus on online harms leaves critical questions of process underexplored in the policy process. We have shown that (i) codes of conduct or practice, (ii) special status and behavioral obligations for strategic platform firms, and (iii) reporting requirements are three perceived procedural solutions to the paradigm shift demanded by policymakers toward platforms demonstrating their “responsibility.” We suggest that the details matter in this context. Critical questions include how to monitor activities (e.g. by using information-gathering powers); how to trigger intervention; and how to remove or prevent undesirable content. These questions need to be open to empirical investigation, not only by the regulators themselves but also by independent researchers and journalists. This should involve scrutiny of filtering and recommendation technologies, notification and redress processes, and, more generally, access to data to enable transparency. 20

In the UK context, we have made visible the network centrality of three agencies – Ofcom, the CMA, and the ICO. This triad has become the weight-bearing structure for the development of distinct new regulatory powers relating to content, markets, and data. But the present additive approach taken to complementing the scope of existing regulatory actors means that the UK is faced with potentially incommensurable rules pursued by different regulators defined by different logics, such as intermediary liability (for content), data protection and privacy (within digital interactions), and competition law (addressing market dominance and innovation).

The UK’s evolving approach points to the pursuit of pragmatic coordination effected between multiple agencies. The CMA, Ofcom, and ICO took the initiative by creating a new Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum. 21 There are agreements in place between these different agencies, which acquired a chief executive in November 2021 to coordinate the forum’s common secretariat. 22 So far, the UK government has opted to allow regulators to strike deals with one another and devise their own common approach by negotiation. This has taken the form of a series of incremental steps taken over two years.

Pragmatic incrementalism, therefore, has been the chosen route to date rather than one of seeking to formalize a hierarchy of actors with a “super-regulator” at the apex endowed with statutory underpinnings. In our view, the “super-regulator” question remains pertinent for internationally comparative work. The specific form taken by regulatory bodies and the way this interplays with the development of regulatory policy is likely to vary according to diverse types of political regime and culture. Technologies typical of online platforms, such as algorithmic identification, targeting and recommender systems may have effects that cut across different agencies’ territories, with wide-ranging cultural, innovation, and fundamental rights effects.

The emergence of the regulatory field captured in our study allows us to relate Bourdieu’s notion of agency and structure in concrete ways. We have shown how regulatory bodies depend either on their creation by the state – or, otherwise, on the political regime’s recognition of their claims to relevant competence. At the margin, where national security concerns weigh large, a more covert approach to regulation may be taken. In general, though, it is the public recognition of the state’s official imprimatur that affords legitimacy to a regulatory body. In the UK, public agencies such as regulators are normally vested with powers according to an “arm’s-length principle” that is intended to demonstrate their autonomy, a status publicly characterized as having “independence” from direct political influences.

This claim is still symbolically important as a feature of the political culture, even though appointments to key public bodies are sometimes disputably politicized. 23 As observed, those regulators presently at the core of the structure all have statutory authority as their underpinnings: these enjoy the highest level of “consecration,” to use Bourdieu’s term, and are positioned to grant or withhold symbolic recognition by virtues of their decisions. Even in the case of civic or industry-based initiatives that have been co-opted into regulation by the state, formally recognized bodies are inescapably shaped by the relations of political power that define the scope of their regulatory roles. In that sense, they too are legitimized.

In response to societal unease about “online harms,” the law offers subject domain choices (ranging from the areas of competition to communications and privacy), confers obligations and endows regulatory agencies with investigatory and enforcement powers that stand in mutually unstable power relations to each other as well as vis-à-vis shifting executive and legislative interventions. In the UK, the key agencies’ collective response was to form a coalition to negotiate their respective competences between themselves. Their joint gesture in acceptance of the prevailing post-Brexit realpolitik was to offer a flexible framework based on “codes of practice” or “codes of conduct” that also spoke to the “Global Britain” agenda, seeking convening advantages in the post-Brexit context.

The coordinated emergence of British regulators is of theoretical interest for field theory, as an instance of negotiating power at national level, while at the same time offering a possible transnational model with similarities to and differences from the EU approach from which the UK is seeking to diverge. Does the regulatory field emerge as law giving content ex ante (specifying rules), or ex post (leaving courts or regulators to apply standards to unforeseen and unforeseeable scenarios)? How do private rules (such as “terms of service”) become enforceable under state powers? Many open questions remain. The UK’s new regulatory arrangements are still interim and untested, as are the effectiveness of competing approaches, such as the EU’s. A transnational regulatory field formed by regulatory agencies around the emerging pillars of content, data, and competition harms is emerging but has not yet taken form.

References

Balkin, J. (2014). Old-school/new-school speech regulation. Harvard Law Review, 127, 2296–2341.

Barr, K. and Kretschmer, M. (2022, May 12). Channel 4: Streaming on the world stage? Competing in the changing media landscape. AHRC Creative Industries Policy & Evidence Centre. https://pec.ac.uk/blog/can-channel-4-compete-on-the-world-stage

Bourdieu, P. (1993). The field of cultural production. Columbia University Press.

Braithwaite, J. and Drahos, P. (2000). Global business regulation. Cambridge University Press.

Celeste, E. (2019). Terms of service and bills of rights: New mechanisms of constitutionalisation in the social media environment? International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 33(2), 122–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600869.2018.1475898

Chibber, K. (2014, December 1). American cultural imperialism has a new name: GAFA. Quartz. https://qz.com/303947/us-cultural-imperialism-has-a-new-name-gafa/

Conservative and Unionist Party (2017). Forward, Together: Our Plan for a Stronger Britain and a Prosperous Future. The Conservative and Unionist Party Manifesto 2017.

CREATe (2020). Platform regulation resource page. https://www.create.ac.uk/platform-regulation-resource-page/

Downs, A. (1972). Up and down with ecology: The “issue-attention cycle.” Public Interest, 28, 38–51.

Durrant, T. (2022). Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police Service. Institute for Government. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/commissioner-metropolitan-police

Eben, M. (2021, March 23). Gating the gatekeepers (2): Competition 2.0? CREATe. https://www.create.ac.uk/blog/2021/03/23/gating-the-gatekeepers-2-competition-2–0/

Emirbayer, M. and Johnson, V. (2008). Bourdieu and organizational analysis. Theory and Society, 37(1), 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-007-9052-y

Flew, T., Martin, F. and Suzor, N. (2019). Internet regulation as media policy: Rethinking the question of digital communication platform governance. Journal of Digital Media & Policy, 10(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1386/jdmp.10.1.33_1

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press.

Google (2021). Content delistings due to copyright. Google Transparency Report. https://transparencyreport.google.com/copyright/overview?hl=en_GB

Gorwa, R. (2019a). What is platform governance? Information, Communication & Society, 22(6), 854–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1573914

Gorwa, R. (2019b). The platform governance triangle: Conceptualising the information regulation of online content. Internet Policy Review, 8(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.2.1407

Gorwa, R., Binns, R. and Katzenbach, C. (2020). Algorithmic content moderation: Technical and political challenges in the automation of platform governance. Big Data & Society, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951719897945

Kaplow, L. (1992). Rules versus standards: An economic analysis. Duke Jaw Journal, 42(3), 557–629.

Kosseff, J. (2019). The twenty-six words that created the Internet. Cornell University Press.

Kretschmer, M. (2020a). Regulatory divergence post Brexit: Copyright law as an indicator for what is to come. EU Law Analysis. http://eulawanalysis.blogspot.com/2020/02/regulatory-divergence-post-brexit.html

Kretschmer, M. (2020b). Gating the gatekeepers. AHRC Creative Industries Policy & Evidence Centre. https://pec.ac.uk/blog/gating-the-gatekeepers

Kretschmer, M. and Schlesinger, P. (2021). The birth of neo-regulation. AHRC Creative Industries Policy & Evidence Centre. https://pec.ac.uk/policy-briefings/the-birth-of-neo-regulation-where-next-for-the-uks-approach-to-platform-regulation

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). SAGE.

Maier-Rigaud, F. and Loertscher B. (2020). Structural vs. behavioural remedies. Competition Policy International. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3569642

Moore, M. and Tambini, D. (eds.) (2018). Digital dominance: The power of Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple. Oxford University Press.

Moore, M. and Tambini, D. (eds.) (2022). Regulating big tech: Policy responses to digital dominance. Oxford University Press.

Napoli, P.H. (2019). Social media and public interest: Media regulation in the disinformation age. Columbia University Press.

Newton, C. (2019, February 25). The trauma floor: The secret lives of Facebook moderators in America. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2019/2/25/18229714/cognizant-facebook-content-moderator-interviews-trauma-working-conditions-arizona

Open Rights Group (2021a). Counter-Terrorism Internet Referral Unit. https://wiki.openrightsgroup.org/wiki/Counter-Terrorism_Internet_Referral_Unit

Open Rights Group (2021b). Counter-Terrorism Internet Referral Unit/Lumen reports. https://wiki.openrightsgroup.org/wiki/Counter-Terrorism_Internet_Referral_Unit/Lumen_reports

Peukert, A., Husovec, M., Kretschmer, M., Mezei, P., and Quintais, J.P. (2021). European Copyright Society – Comment on Copyright and the Digital Services Act Proposal. International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law (IIC), 53, 358–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40319-022-01154-1

Rajan, A. (2022, March 24). Lord Michael Grade chosen as Ofcom chairman. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-60845520

Schlesinger, P. (2020). After the post-public sphere. Media, Culture & Society, 42(7-8), 1545–1563. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720948003

Schlesinger, P. (2022). The neo-regulation of Internet platforms in the United Kingdom. Policy & Internet, 14(1), 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.288

Schlesinger, P., Selfe, M. and Munro, E. (2015). Curators of cultural enterprise: A critical analysis of a creative business intermediary. Palgrave Macmillan.

Smith, G. (2020, December 17). The Online Harms edifice takes shape. Cyberleagle. https://www.cyberleagle.com/2020/12/the-online-harms-edifice-takes-shape.html

Suzor, N. (2019). Lawless: The secret rules that govern our digital lives. Cambridge University Press.

Van Dijck, J., De Waal, M. and Poell, T. (2018). The platform society: Public values in a connective world. Oxford University Press.

Woods, L. (2019). The duty of care in the Online Harms White Paper. Journal of Media Law, 11(1), 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17577632.2019.1668605

Wooldridge, A. (2013, November 18). The coming tech-lash: The tech elite will join bankers and oilmen in public demonology. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/news/2013/11/18/the-coming-tech-lash

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. Profile Books.

Legal and governmental sources

Australia

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2019). Digital Platforms Inquiry. Final report. https://www.accc.gov.au/publications/digital-platforms-inquiry-final-report

Treasury Laws Amendment (News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code) Act 2021 (2021). Federal Register of Legislation. No. 21, 2021. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2021A00021

European Union

Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2000 on certain legal aspects of information society services, in particular electronic commerce, in the Internal Market (“Directive on electronic commerce”) (2000). Official Journal L178/1. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/31/oj

Directive (EU) 2019/790 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC (2019). Official Journal L130/92. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/790/oj

European Commission (2016). Communication from the European Commission to the European Parliament, the Council the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—Online Platforms and the Digital Single Market: Opportunities and Challenges for Europe (COM/2016/0288 final). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52016DC0288

European Commission (2020a). Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on a Single Market For Digital Services (Digital Services Act) and amending Directive 2000/31/EC (COM/2020/825 final). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?qid=1608117147218&uri=COM%3A2020%3A825%3AFIN

European Commission (2020b). Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act) (COM/2020/842 final). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?qid=1608116887159&uri=COM%3A2020%3A842%3AFIN

European Commission (2022). The Digital Services Act package. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-services-act-package

France

LOI n° 2020–766 du 24 juin 2020 visant à lutter contre les contenus haineux sur internet (2020). JORF n°0156. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000042031970

Germany

Gesetz zur Verbesserung der Rechtsdurchsetzung in sozialen Netzwerken (Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz—NetzDG) (2017). BGBl. I S. 3352. https://www.bmjv.de/DE/Themen/FokusThemen/NetzDG/NetzDG_node.html

India

Electronics and Information Technology Ministry (2021). The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules. https://prsindia.org/billtrack/the-information-technology-intermediary-guidelines-and-digital-media-ethics-code-rules-2021

Poland

Ministerstwo Sprawiedliwości (2021). Projekt z dnia 15 stycznia 2021. Ustawa o ochronie wolności słowa w internetowych serwisach społecznościowych. https://www.gov.pl/web/sprawiedliwosc/zachecamy-do-zapoznania-sie-z-projektem-ustawy-o-ochronie-wolnosci-uzytkownikow-serwisow-spolecznosciowych

United Kingdom

Advertising Standards Authority (2020). Recognising ads: Social media and influencer marketing. https://www.asa.org.uk/advice-online/recognising-ads-social-media.html

Cairncross, F. (2019). Cairncross Review. A sustainable future for journalism. Department of Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-cairncross-review-a-sustainable-future-for-journalism

Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (2019). Centre for Data Ethics (CDEI) 2 Year Strategy. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-centre-for-data-ethics-and-innovation-cdei-2-year-strategy/centre-for-data-ethics-cdei-2-year-strategy

Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (2020). Review of online targeting. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cdei-review-of-online-targeting

Competition and Markets Authority (2019). Online platforms and digital advertising. Market study interim report. https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/online-platforms-and-digital-advertising-market-study

Competition and Markets Authority (2020). Online platforms and digital advertising. Market study final report. https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/online-platforms-and-digital-advertising-market-study

Competition and Markets Authority (2021). Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (DRCF) work plan for 2021/22 [Policy paper]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/digital-regulation-cooperation-forum-workplan-202122

Crown Prosecution Service (2004). Memorandum of Understanding Between the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) concerning section 46 Sexual Offences Act 2003. https://www.cps.gov.uk/publication/memorandum-understanding-between-crown-prosecution-service-cps-and-national-police

Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy and Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. (2020, November 27). New competition regime for tech giants to give consumers more choice and control over their data, and ensure businesses are fairly treated [Press release]. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-competition-regime-for-tech-giants-to-give-consumers-more-choice-and-control-over-their-data-and-ensure-businesses-are-fairly-treated

Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport and Home Office (2019). Online Harms White Paper (CP 57). https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/online-harms-white-paper

Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport and Home Office (2020). Online Harms White Paper: Full government response to the consultation (CP 354). https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/online-harms-white-paper/outcome/online-harms-white-paper-full-government-response

Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (2021) Government response to the House of Lords Communications Committee’s report on Freedom of Expression in the Digital Age. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/7704/documents/80449/default/

Department for Exiting the European Union (2019). Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community [policy paper]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/new-withdrawal-agreement-and-political-declaration

Furman, J. (2019). Unlocking digital competition. Report of the Digital Competition Expert Panel. Treasury and Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/785547/unlocking_digital_competition_furman_review_web.pdf

HM Government (2021). Global Britain in a Competitive Age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (CP 403). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age-the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy/

HM Government (2022). Online Safety Bill (A Bill to make provision for and in connection with the regulation by OFCOM of certain internet services; for and in connection with communications offences; and for connected purposes). https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3137

HM Government (2022). A new pro-competition regime for digital markets - government response to consultation (CP 657). https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/a-new-pro-competition-regime-for-digital-markets/outcome/a-new-pro-competition-regime-for-digital-markets-government-response-to-consultation

Home Office (2015). Prevent duty guidance. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prevent-duty-guidance

House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee (2019). Disinformation and “fake news” (HC 1791). https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmcumeds/1791/1791.pdf

House of Commons Library (2019). The Status of “Retained EU Law” (Briefing Paper No 08375). https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8375/

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee (2020). A brave new Britain? The future of the UK’s international policy (HC 380). https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/3133/documents/40215/default/

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee (2021). A brave new Britain? The future of the UK’s international policy: Government Response to the Committee’s Fourth Report (HC 1088). https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/4225/documents/43246/default/

House of Lords Communications Committee. (2019). Regulating in a digital world (HL 299). https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201719/ldselect/ldcomuni/299/299.pdf

House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee. (2021). Digital regulation: Joined up and accountable (HL 126). https://committees.parliament.uk/work/1409/digital-regulation/publications/

Ofcom (2018). Discussion Paper: Addressing harmful online content: A perspective from broadcasting and on-demand standards regulation. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/120991/Addressing-harmful-online-content.pdf

Security Services Act 1989. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1989/5/contents

Security Service, MI5 (2022). Gathering intelligence. https://www.mi5.gov.uk/gathering-intelligence

United States

Communications Decency Act (CDA) (1996) 47 U.S.C. § 230

Digital Millennium Copyright Act (1998) 17 U.S.C. § 512

Subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee inquiry (2020). Investigation of competition in the digital marketplace: Majority staff report and recommendations. https://judiciary.house.gov/uploadedfiles/competition_in_digital_markets.pdf?utm_campaign=4493-519

[All online sources reviewed on October 1, 2022]

Date received: January 2022

Date accepted: May 2022

1 Martin Kretschmer is Professor of Intellectual Property Law, Dr Ula Furgał is Lecturer in Intellectual Property and Information Law, Philip Schlesinger is Professor in Cultural Theory, all at CREATe, University of Glasgow. The research has been supported by AHRC Centre of Excellence for Policy & Evidence in the Creative Industries (PEC) (reference: AH/S001298/1) and Kretschmer’s Weizenbaum fellowship. Earlier versions of this paper have been presented at the British Institute of International and Comparative Law (BIICL) on February 26, 2020, at the platgov.net conference on 24 March, 2021 and at the Munich Summer Institute (MSI) on 10 June, 2022. We are grateful for comments received on these occasions, in particular a detailed response from Stefan Bechtold at the MSI. Personal thanks to Peter Drahos for hospitality and advice at the design stage.

2 The first legal reference to “online platforms” as a distinct regulatory object can be found in Online platforms and the digital single market (European Commission 2016). Arguably, the first statutory intervention of a new kind is Germany’s “Netz DG” legislation of 2017 which qualified the safe harbor that shielded internet intermediaries from liability for what their users do on their services (Netz DG 2017). The law defines its target as social networks with over 2 million users in Germany. In many jurisdictions, legislative interventions and inquiries have followed in close succession. In Australia, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission conducted an inquiry into digital platforms (ACCC 2019), which led to the adoption of the News Media Bargaining Code in 2021. In the European Union (EU), Art. 17 of the Copyright Directive (Directive (EU) 2019/790) provided for a new regime of intermediary liability for certain content-sharing services. The proposals for the Digital Services Act (European Commission 2020a) and Digital Markets Act (European Commission 2020b) outline new rules for digital platforms. In 2020, France adopted a new law on online hate speech (“Avia law”, LOI n° 2020–766 du 24 juin 2020 visant à lutter contre les contenus haineux sur internet), which was declared unconstitutional the same year. In the UK, following publication of the Online Harms White Paper (DCMS and Home Office 2019), the government committed itself to the introduction of an online duty of care, which would be overseen by an independent regulator, Ofcom (DCMS and Home Office 2020). The UK also established a Digital Markets Unit under the aegis of the competition authority CMA (DBEIS and DCMS 2020). In Poland, a proposal for creation of a Council of Freedom of Speech (Rada Wolności Słowa) to police content removals online was tabled in 2021 (MS 2021). India has adopted a new set of rules for social media platforms, Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules 2021 (Electronics and Information Technology Ministry 2021). In the US, the discussion on repeal or amendment of s. 230 (CDA 1996) is ongoing, in parallel with Antitrust reviews (such as the Subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee (2020) inquiry into online platforms and market power).

3 US norms: Communications Decency Act (CDA) of 1996, s. 230: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider” (47 USC s. 230); Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, s. 512 specifies a formal procedure under which service providers need to respond expeditiously to requests from copyright owners to remove infringing material (notice-and-takedown). EU norms: e-Commerce directive (2000/31/EC): Arts. 12–14 provide a safe harbor for service providers as conduits, caches, and hosts of user information; under Art. 14, “the service provider is not liable for the information stored at the request of a recipient of the service” if removed expeditiously upon obtaining relevant knowledge (notice-and-action); Art. 15 prevents the imposition of general monitoring obligations.

4 Agreement and political declaration on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union (DEEU 2019). On regulatory divergence post-Brexit, see Kretschmer 2020a.

5 New competition regime for tech giants to give consumers more choice and control over their data, and ensure businesses are fairly treated (DBEIS and DCMS 2020); Online Harms White Paper: Full government response to the consultation (DCMS and Home Office 2020). For an overview, exploring the relationship to EU digital market interventions, see Kretschmer (2020b) and Eben (2021). For a legal analysis of the UK proposal to introduce an online duty of care, see Woods (2019) and Smith (2020). For a discussion of the successive steps taken in establishing the Digital Markets Unit in the context of a neo-regulatory drive, see Schlesinger (2022).

6 For the purposes of content analysis, we rely on the interim report (283 pp.) which contains the core diagnostic assessment and was published within the 18-month period under investigation where we focus on one cycle of issues that are signaled as demanding attention. The final CMA report was published in July 2020, extending to 437 pp., and setting out the case for a new pro-competitive regulatory regime as well as proposed interventions.

7 The oral comments made on the day – endorsed by email when confirming the online documentation of the event (CREATe 2020) – should therefore be understood as contributing additional primary material to this analysis. While this exchange with regulatory personnel has been incorporated into the interpretation of findings in the concluding section of this article, the present study was undertaken entirely independently of the regulators consulted.

8 Following Brexit, existing EU law has been converted into UK law, with the exception of the Charter on Fundamental Rights (House of Commons Library 2019).

9 Contrast for example the balancing of fundamental rights underpinning the EU GDPR of 2016 (“The processing of personal data should be designed to serve mankind,” Recital 4) with the minimal government considerations implicit in the liability shield of s. 230 of the US Communications Decency Act of 1996 (“the twenty-six words that created the Internet,” Kosseff 2019).

10 Facebook alone employs about 35,000 human content moderators (who are mostly outsourced). For their working conditions, see Newton (2019).

11 The announcements by the UK government in December 2020 of the Digital Market Unit within CMA (DBEIS and DCMS 2020) and Ofcom’s role as Online harms regulator (DCMS and Home Office 2020) could have been predicted from this analysis of earlier reports. This development offers support for our methodological approach. The issue-attention cycle that ran for a period of 18 months early in the parliamentary period resulted in an attempt to cover the waterfront of platform activity.