Platform Matters

Political Opinion Expression on Social Media

1 Introduction

Scholarship has focused on the role of discussion in an informed and active citizenry, stressing the role of interpersonal communication within the political process (Katz & Lazarsfeld, 2017; Habermas, 1989; Manin, 1987). Through everyday political conversation, citizens build their identities (Kim & Kim, 2008; Ekström & Östman, 2015), acquire information (Scheufele, 2000), achieve mutual understanding (Moy & Gastil, 2006; Pingree, 2007), and produce public reasoning and knowledge (Bennet, Flickinger & Rhine, 2000; Eveland & Hively, 2009). Research has established the value of citizens’ conversations about public issues as a necessary condition for the healthy functioning of democratic societies (Dewey, 1927; Katz & Lazarsfeld, 2017; Bennet, Flickinger, & Rhine, 2000).

Informal political talk – defined as non-purposive, spontaneous conversations around political issues that are free from any formal procedural rule and predetermined agenda (Habermas, 1984) – has been considered an important component of democracy since everyday political talk is a key aspect of the deliberative system (Mansbridge, 1999; Conover & Searing, 2005; Kim & Kim, 2008; Fraser, 1990; Valenzuela, Kim, & Gil de Zúñiga, 2012; Gil de Zúñiga, Valenzuela, & Weeks, 2016). Social media have become a critical tool towards this end because they furnish “citizens with opportunities to express themselves and openly share their ideas, opinions and viewpoints” (Gil de Zuñiga, Huber, & Strauss, 2018, p. 1173).

Scholarship on political discussion on social media has either tended to subsume all platforms under the general “social media category” (Gil de Zúñiga, Weeks, & Ardèvol-Abreu, 2017) or conduct research on one platform and assume that findings are valid across different channels (Gil de Zuniga, Huber, & Strauss, 2018; Pingree, 2007). However, notable exceptions to this scholarly trend indicate that political discussion on these platforms depends on user motivations, technological affordances, network structure, and dominant communicative practices (Duffy, Pruchniewska, & Scolere, 2017; Skoric, Zhu, & Pang, 2015; Valenzuela, Kim, & Gil de Zúñiga, 2012; Settle, 2018; Yarchi, Baden, & Kligler-Vilenchik, 2020). Our paper draws theories of polymedia and context collapse (Costa 2017; Davis & Jurgenson, 2014; Miller & Madianou, 2012; Marwick & Boyd, 2011) to examine how users of different social media platforms engage or fail to participate in political discussion. Drawing upon survey and interview data, we analyze how people in Argentina perceive and communicate on Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, and Instagram.

As Kessler et al. (2020) propose, studies on social dynamics in polarizing contexts are limited by their reliance on either surveys or in-depth interviews. For this reason, this study combines both methods to shed light on the differences and similarities of political conversations on social media platforms in a country marked by widespread polarization since 2008 (De Luca & Malamud, 2010).

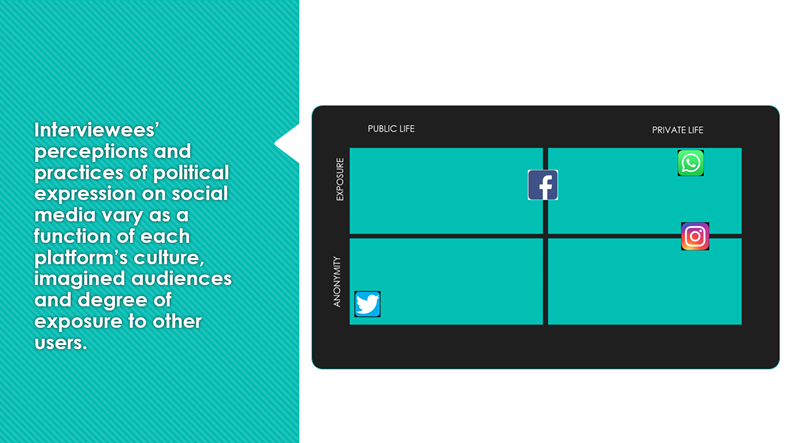

Our findings show the existence of divergent dynamics of political conversation across platforms. The interviews indicate that users locate Facebook at the intersection between private life and public life, expecting lower levels of anonymity; perceive Twitter as a relatively anonymous space for the discussion of mostly public affairs; use Instagram, where they expect their contacts to recognize them, mostly for non-political content; and experience WhatsApp as a platform for management of their everyday life where they expect their contacts to know who they are. Furthermore, the survey finds that, while the use of Facebook and Twitter was positively associated with posting political opinions on social media, the same pattern was not present for WhatsApp and Instagram. Perceptions of political talk and engagement in discussion vary according to the platform on which they take place, but not in relation to users’ demographic characteristics. We draw on these findings to reflect on how varying user practices contribute to understanding social media platforms as culturally distinct spaces, and what this means for the role of socially mediated political talk in contemporary societies.

2 Theoretical considerations

2.1 Online political talk and incivility: personal and political dimensions

The online environment has enabled new forms of political participation (Jung, Kim, & De Zúñiga, 2011; Valenzuela, Kim, & Gil de Zúñiga, 2012; Boulianne, 2015; Bennett & Segerberg, 2012; Gil de Zúñiga, Molyneux, & Zheng, 2014; Gil de Zúñiga, Weeks, & Ardèvol-Abreu, 2017; Pingree, 2007; Kim, Hsu, & de Zúñiga, 2013; Kushin & Yamamoto, 2010). Research shows a mainly positive link between digital media use and political participation (Boulianne, 2015, 2018), where political expression is an important antecedent of political participation (Bennett & Segerberg, 2012), as “political talk precedes political action” (Gil de Zúñiga, Huber, & Strauss, 2018, P. 1174).

Regarding the political dimension, civil political discourse is generally thought to be central to a well-functioning democracy (Hopp & Vargo, 2017). Scholarship on Latin America suggests that there is a relationship between polarization and a growing erosion of democracy (Kessler et al., 2020; Lupu Oliveros, & Schiumerini, 2020). De Luca and Malamud (2010, p. 174) propose that that, beginning in 2008, Argentina experienced the highest degree of social and political polarization since the first presidency of Juan Perón (1946-1955). In 2018 the government decided to raise taxes on agricultural exports, thus unleashing long-lasting conflict between then-president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and the agricultural producers – and, by extension between Kirchnerists and non-Kirchnerists. Indeed, since 2008, the Kirchnerist administrations (2003-2015) publicly confronted the main Argentine media group, Clarín, which they identified as one of the actors in the opposition (Kitzberger, 2012).

Polarization might be intensified by the propensity of people to accept information that coincides with their pre-existing views, and that this new information should strengthen these views (Birch, 2020). Indeed, the massification of networks, consolidated during the 2010s, intensified a pre-existing political polarization (Baldoni & Schuliaquer, 2020). For instance, in Aruguete & Calvo (2018) analysis of the coverage on Twitter of #Tarifazo protests in Argentina – a political crisis triggered by the decision of Mauricio Macri’s administration (2015-2019) to increase public utility rates by 400% – the messages delivered by pro- and anti-government users were activated in different regions of the network, with scant information crossing to the opposite camp. Studies also indicate that polarization has potentially limiting effects on the scope of political conversations (Eliasoph, 1998; Mutz, 2002; Lee et al., 2014; Yarchi, Baden, & Kligler-Vilenchik, 2020; Huckfeldt et al., 2004). Therefore, research about online discussions suggests that exposure to uncivil comments, understood as “features of discussion that convey an unnecessarily disrespectful tone toward the discussion forum, its participants, or its topics” (Coe, Kenski, & Rains, 2014, p. 660), have negative political and personal consequences.

Vis-à-vis the personal dimension, dangerous discussions (Eveland & Hively, 2009) and online incivility may elicit anger, aversion, guilt, aggression, and/or anti-deliberative attitudes (Anderson et al., 2018; Goyanes, Borah, & Zúñiga, 2021; Coe, Kenski, & Rains, 2014). In this sense, social media sites constantly collapse multiple social contexts (Davis & Jurgenson, 2014) potentially resulting in self-censorship behaviors, as individuals selectively self-present through these platforms (Velasquez & Rojas, 2017; Sibona, 2014). For instance, Goyanes, Borah and Zúñiga (2021) find that people who discuss online about politics in an uncivil manner are more prone to filter or block the users they follow or are in contact with. Likewise, Lee and Choi (2020) conclude that individuals within heterogeneous social media environments who engage more often in political discussion have more polarized opinions than those who seldom participate in political talk.

Moreover, scholarship indicates that not all citizens are equally likely to engage in political opinion expression. Research shows that the mean for online expression is lower than that for offline political talk (Bode et al., 2014). Young adults are more likely than their older counterparts to express their political opinions on social media, including voicing support for a candidate, sharing news articles, and discussing politics with other users (Rainie et al., 2012; Smith & Duggan, 2012; Yamamoto, Kushin, & Dalisay, 2015). Besides, more educated and wealthy citizens are more inclined to engage in civic activities than their less educated and less welloff counterparts (Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, 1995; Zukin et al., 2006). For instance, Portney and O’Leary (2007) find that people with higher levels of educational attainment and income tend to engage more frequently in online political discussions. In addition, while women have made considerable gains in wielding political influence, research indicates that they engage less than men in political discussions (Huckfeldt & Sprague, 1995; Wen, Xiaoming, & George, 2013; Vochocová, Štětka, & Mazák, 2 016).

2.2 Various uses of platforms

In relation to political and personal aspects, polymedia theory (Costa, 2017; de Bruin, 2017; Miller & Madianou, 2012; Peng, 2016; Renninger, 2015; Zhou, Liang, & Zhang,, 2015) proposes that social actors privilege relational and emotional matters when selecting communication channels rather than technological affordances. Madianou (2014) argue that emphasis should be made “on how users exploit the affordances within the composite structure of polymedia in order to manage their emotions and relationship (p. 671). The affordances of social media platforms invite different types of user interactions and promote the emergence of distinct networks and practices (Papacharissi, 2009; Zhang & Wang, 2010). Platforms enable parties, candidates, and politicians to directly reach out to citizens, mobilize supporters, and seek to influence the public agenda. Through social media, they can bring their message to the public faster, posting on recent events before they are interpreted by news media (Stieglitz & Dang-Xuan, 2012). Due to the various architectures of social media platforms, politicians use different platforms in diverse ways (Stier et al., 2018), and thus, sentiment and conversation styles differ across platforms (Lin & Qiu, 2013; Hsu & Park, 2012; Caton, Hall, & Weinhardt,, 2015).

Studies about political expression on social media have found important differences across platforms (Becker & Copeland, 2016; Lu & Myrick, 2016; Vaccari et al., 2015; Yamamoto, Kushin, & Dalisay, 2015). Valeriani and Vaccari (2018) find that platform affordances have relevant implications on the types of users favoring political expression and conversation. In fact, following Schmidt´s analytical framework (2007), we can recognize, two types of rules regarding exposure of users and type of content of posts. First, regarding the personal aspect, the exposure spectrum refers to the scale of privacy users expect on social media platforms, ranging from exposure to anonymity. Second, on the political dimension, there is a continuum with respect the kind of content related to either private life or public affairs. In the next paragraphs we present some differences found by the literature on the respective uses and perceptions of Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram.

An increasing number of studies have focused on the role of Twitter in politics. Twitter’s unique design and its capability to disseminate information have attracted considerable research interest (Hsu & Park, 2012). Yang and Counts (2010) discussed Twitter’s critical role in information diffusion and other studies found that conversations are often structured by political hashtags (Bruns & Burgess, 2011; Boynton, 2013) around which ad hoc publics (Bruns & Burgess, 2011; Vaccari & Valeriani, 2018) emerge. Moreover, “super-participants”, who tend to work in politics, hold important positions in discussion networks (Larsson & Moe, 2012). Marwick and Boyd (2011) show that some regular Twitter users with public accounts imagined their audience to be a general public, while others imagined it to be friends, family, or interested parties. Usher, Holcomb and Littman (2018) found that male journalists are more likely to have a verified Twitter account as a sign they are a “public figure,” to have more followers and to tweet more often.

Scholarship has found that Facebook is perceived as a less anonymous space (Boczkowski, Mitchelstein, & Matassi, 2018; Semaan et al., 2014; Hampton, Lee & Her, 2011; Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2011). Halpern and Gibbs (2013) have analyzed interactions on the Facebook and YouTube channels of the White House, finding that the greater anonymity of YouTube debates leads to more flaming and impoliteness than Facebook. Popular public pages of news outlets, politicians, activist groups, and celebrities often host political threads involving previously unconnected strangers, anchoring political discussions in pre-existing networks (Vaccari & Valeriani, 2018).

Research shows that users perceive Instagram as part of a broader context of ‘political talk’ where images are “not the displays of the rulers, but rather, the rhetoric of subaltern counter publics” (Mahoney & Tang, 2016). Although research on Instagram as a venue for political expression is scarce, Trevisan et al. (2019) found that in Italy before the European Elections of May 2019 a small group of users actively participated in discussions and reply to other comments, aiming at influencing the online political debate.

In contrast, WhatsApp is used mainly to maintain connections with family members, friends, and acquaintances, and to chat within small groups in private settings, rather than discussing political topics with larger groups (O’Hara et al., 2014; Matassi, Boczkowski, & Mitchelstein, 2019; Marwick & Boyd, 2011; Karapanos Teixeira, & Gouveia, 2016; Valenzuela, Bachmann, & Bargsted, 2021).

As mentioned above, Argentina is a fruitful setting to examine political talk in a polarized context for two main reasons. First, the 2015 presidential election was one of the most polarized in history (Lupu, 2016; Rodriguez & Smallman, 2016). National and international observers labeled the division between the two main parties, Peronist Frente de Todos (Kircherismo) and Cambiemos (Macrismo) as “la grieta” or, “the chasm” (Lupu, Oliveros, & Schiumerini, 2020). Second, Argentina has a high proportion of social media users, over 70 percent (Freedom House, 2018). Filer and Fredheim state: “the attention that Argentine politicians pay to social media suggests that they recognize the widespread use of these online platforms in Argentina, particularly among the youngest segment of the newly expanded electorate” (2017, p. 261). Use of social media varies by platform. According to the 2018 Reuters Digital News Report, 80% of survey respondents used Facebook and WhatsApp, compared to 42% who were on Instagram, and 29% on Twitter (Levy, Newman, & Fletcher, 2018)

2.3 Research questions and hypothesis

Informed by scholarship discussed in the previous section, we start our research with two-part quantitative hypothesis:

- H1a: Younger people post more personal opinions about politics, economics, and current affairs on social media platforms than older respondents.

- H1b: Men post more personal opinions about politics, economics, and current affairs on social media platforms than women.

- H1c: People with higher levels of education post more personal opinions about politics, economics, and current affairs on social media platforms.

- H1d: People of higher socioeconomic status post more personal opinions about politics, economics, and current affairs on social media platforms.

- H2: Twitter users post more personal opinions about politics, economics, and current affairs than Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp users.

To explore how users engage in political talk on different social media platforms we then pose two research questions:

- RQ 1: How do users make sense of varying opinion expression practices in different social media platforms?

- RQ 2: How do users engage in opinion expression practices?

3 Methodology

This comparative cross-platform study combines in-depth interviews with a survey to examine the socio-demographic factors that explain opinion expression on varying social media platforms, and the interpretations and experiences tied to that expression.

First, this paper draws on a 2016 survey of 700 people from the Greater Buenos Aires area, which comprises 37% of the Argentina population (INDEC, 2010), to analyze how the use of different social media platforms is related to online political expression in Argentina. The survey was conducted face-to-face during October 2016. The sample consists of a diverse group regarding gender, age, and socioeconomic status. Households were selected according to a probabilistic multi-stage sample design, and respondents were selected to complete age and gender quotas. Of the 700, 175 were 18- to 29-years-old, 175 were 30–44, 175 were 45–60, and 175 were 60 or older. While the average age of the Argentine population as of the 2010 National Census is 29 years old, the average age of the sample, which does not include persons under 18 years of age, is 44.94 years (INDEC, 2010). Half of the sample was female, and the survey response rate was 19%. Their mean age was forty.

The dependent variable is the frequency with which respondents posted personal opinions about politics, economics, and current affairs in general on social media. The survey question was “Could you tell me whether you use social media to post personal opinions about politics, economics and current affairs, and how often?” and the variable is ranged from 1 (never) to 8 (several times a day). The independent variables are social media frequency of use for Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp (variables were dichotomized as 1 if respondents use the platforms constantly or several times a day and 0 if respondents they use it once a day or less). We also include gender, age, education attainment, and socioeconomic status.

Second, the research also draws on one-hundred-and-fifty-eight semi-structured interviews – 56.33% female and 43.67% male – conducted face-to-face by a team of research assistants in the Greater Buenos Aires Area, and the provinces of Córdoba, Santa Fe and Salta, between March 2016 and December 2017. All interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed in their entirety, lasting an average of approximately 33 minutes. In most cases, the recruitment of interviewees started by inviting a handful of distant contacts of each interviewer to be interviewed. These contacts were a diverse group in terms of gender, age group, and socio-economic status. At the end of the interview, each interviewee was requested names of three to five of their acquaintances who were diverse in terms of gender, age group, occupation, and socioeconomic level. The interviewer also requested permission to contact these acquaintances for the purposes of this study. Using a grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), the interviews were analyzed through two rounds of coding by the authors. The quotes included in this paper were translated from Spanish into English by the authors. To protect the privacy of participants, we anonymized quotes and used pseudonyms.

Method triangulation (Denzin, 1978) was used to validate findings and their interpretation. Combining in-depth interviews with a survey allowed this research to examine the differences in relation to perceptions and practices about political opinion expression across different platforms and to establish quantitative differences among populations and platforms.

4 Findings

4.1 Survey findings: sociodemographic characteristics and platform use

To estimate the relationship between users’ political expression, sociodemographic characteristics and use of social media platforms, this study specified a linear regression model, (Table 1). Regarding H1a, age is not significantly associated to the frequency of posting personal opinions about politics, economics, and current affairs on social media platforms, and thus, this hypothesis is rejected. Regarding H1b, gender is not significantly associated to the frequency of posting personal opinions on social media platforms, and thus, this hypothesis is rejected. Regarding H1c, level of education is negatively related with posting personal opinions about politics, economics, and current affairs on social media platforms, and thus, this hypothesis is also rejected. Contrary to our hypothesis, people with a higher level of education post fewer opinions on social networks and its coefficient is statistically significant. Regarding H1d, socioeconomic status is not significantly associated with frequency of posting personal opinions on public affairs, and thus, is hypothesis is also rejected.

Regarding H2, Twitter and Facebook use were positively associated with posting opinions, controlling for demographic and media use variables. Going from using Twitter once a day or less to regularly, increases posting personal opinions online by an average of 1,497 on the scale of 1 (never) to 8 (several times a day). In the case of Facebook, its use also increases posting personal opinions in 1.132 on the same scale. While the uses of Instagram and WhatsApp are also positively related to posting personal opinions, these coefficients are not statistically significant. Taking into account the differences among coefficients, the null hypothesis can be rejected. This means that there is a statistically significant difference between being a frequent Twitter user and posting more personal opinions about politics, economics, and current affairs on social networks.

Table 1: Linear regression of “post personal opinions about politics, economics and current affairs” on gender (base case: female), age, socioeconomic status, educational attainment, and Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and WhatsApp frequencies of use.

|

Measure |

Posting personal opinions about politics, |

|

|

Age |

0.000264 |

|

|

(0.110) |

||

|

Male |

-0.114 |

|

|

(0.201) |

||

|

Socioeconomic status |

0.0241 |

|

|

(0.0880) |

||

|

Educational attainment |

-0.182 |

*** |

|

(0.0545) |

||

|

Facebook frequency of use |

1.132 |

*** |

|

(0.244) |

||

|

Twitter frequency of use |

1.497 |

*** |

|

(0.292) |

||

|

Instagram frequency of use |

0.106 |

|

|

(0.288) |

||

|

WhatsApp frequency of use |

0.0977 |

|

|

(0.365) |

||

|

Constant |

2.475 |

*** |

|

(0.590) |

||

|

Observations |

476 |

|

|

R-squared |

0.160 |

** significant at the p < .05 level

* significant at the p < .1 level

4.2 Qualitative findings: personal and political dimensions

Interviewees’ perceptions and practices of political expression of social media vary as a function of each platform’s culture, imagined audiences, and degree of connection to other users. We analyze these matters on each platform on the personal and political dimensions and, in that sense, Figure 1 is the aggregate result of the users’ perceptions that emerged from the in-depth interviews. First, regarding the personal dimension, we focus on the scale of privacy of users on social media platforms expressed as a continuum that goes from exposure to anonymity. Second, at the political dimension, we look at the type of content prevalent on the platforms, whether it is predominantly related to either private life or public affairs (Figure 1). Facebook is located at the intersection between public life and private life, with low levels of expected anonymity; Twitter is in the lower left quadrant, with high levels of anonymity and more content about public affairs; Instagram is on the right side of the matrix, and at the intersection between closeness-anonymity and low levels of political discussion; and WhatsApp is in the lower-righte quadrant, with low almost no expectation and anonymity and low levels of current affairs talk.

Figure 1: Matrix on type of content (political level) and level of privacy (personal level) on social media platforms.

4.3 Personal dimension: anonymity and exposure

Regarding the privacy of users on social media platforms expressed as a continuum from exposure to anonymity, interviewees consider WhatsApp to be a private platform for sharing content about domestic and logistic issues with a close circle of people. Users have the greatest exposure because they know everyone on the platform that is used mostly as a messaging service. Thus, it belongs mostly to the domestic sphere, and interviewees feel they know personally all their contacts and they are known by them. Cecilia, a 32-year-old physical education teacher, said: “I use it a lot at work level, to organize pilates schedules.”1 María, a 46-year-old teaching assistant, added: “I am in the group of parents, I tell you there are two hundred thousand groups, groups of catechesis, groups of everything.”2 Similar to WhatsApp, Instagram interviewees see this network as a relatively private platform, tied to enjoyment and visual content rather than to everyday logistics. It is in the midpoint on the privacy continuum because it is seen as an entertaining, frivolous, and personal space. Respondents share content about topics that they are interested in, which for the most part are related to domestic life issues like cooking, clothing, sports and health. Sofia, the 24-year-old student, explained: “It is more personal and not just anyone joins ... you can control it a little more.”3

WhatsApp is seen as a means to be connected and as a more personal and private space to discuss issues with family and friends. Marta, a 59-year-old housewife said “I have groups with my friends, and we also comment the news”4 Víctor, a 23-year-old college student, commented: “I have so many people on Facebook that I prefer that... I do not like people to know what I am seeing, what I am reading, what my interests are ... but I prefer if I can share it with my friends, send it by WhatsApp to my particular friends or whoever I want to see that news.”5 However, for other users, the closeness of the ties on WhatsApp makes it preferable to express their opinions face-to-face. Andrea, a 77-year-old retired teacher, said: “I don’t like being in a WhatsApp group talking about politics, for example, I don’t like it because it’s like the goal is to have the best reply, beat the other person (…) if I were face to face with that person, I could interpret their body language, and prevent them from saying something outrageous.”6 Natalia, a 31-years old-photographer, stated: “When I agree and when I don’t, I do not want receive those (political) messages on WhatsApp. The phone seems more intimate.”7

In contrast to WhatsApp and Instagram, Twitter is perceived as a platform for information consumption, and it appears to be less permeated by other kinds of content either generated or shared by known friends. It is a space to discuss public affairs topics with people who might or might not know them. Flavia, a 49-year-old software analyst, comments: “Twitter I use it more to read the news (…) because it seems to me that Twitter is used more for that, people post more news, yes, they don’t post so much of their private life and of their personal stories.”8 Thus, we place Twitter at the lower end of the exposure-anonymity axis because it is perceived as a more anonymous space where people are able to consume public information frequently. Sofia, a 24-year-old student, says “Twitter has concise information, which is key when you don’t have time to inform yourself, so you read more or less the information on Twitter and more or less you get an idea. Even if it’s not in depth, you know what is going on.”9 Interviews also perceive that sharing views on Twitter is practical. For instance, Juan, 27-year-old accounting assistant, explains: “although you are limited in what you can say, by the (number of) characters, it is more practical to share what other users write.”10

In the case of Facebook, due to the high level of perceived exposure respondents tend to be more careful on that platform, while on Twitter they express their opinions on politics more freely. On WhatsApp sharing political opinions is associated with trust in other participants; by contrast on Instagram, there seems to be little debate around current issues. In contrast, for the interviewees, Facebook is a source of information, in addition to enabling social connections. Pablo, a 24-years-old sales representative, said that “the news feed shows stories that people share [and posted by] local newspapers. I read the headline, if I’m interested I click on it.”11

On this matter, respondents consider Facebook as a mixture of all the others since it includes social-affective, entertainment and informational aspects, and is seen by interviewees as the oldest, most versatile and complete platform. Marcelo, a 51-year-old security guard said “I am on Facebook for family reasons, I have been on Facebook for years and that will not change.”12 Melina, a 19-year-old student explained “Facebook covers more topics [than other social media]: politics, entertainment, food videos.”13 In this sense, users highlighted the various affordances of this platform. Mario, a 30-year-old account manager said “I use Facebook a lot to see my friends’ stories, and that is a little boring, but I [also] use it as a source of information. [Facebook] includes the things I’m interested in, it is a mix of everything.”14 Respondents also mentioned that Facebook allows them to stay in contact with family, old friends of school and college. Mirta, a 48-year-old accounting assistant, stated: “I like [Facebook] because I am in contact with people I haven’t seen in a long time and I used to work in a school cafeteria (…) so I got in touch the janitors, the teachers, you know.” The imagined audiences are more diverse on Facebook than in the other networks. Federico, 27-year-old motorsports driver says, “On Facebook, since it is older, I have more friends, contacts, followers or whatever they are called, than I have on Instagram or Twitter.”15

Regarding the dimensions of type of content and level of exposure, in Figure 1 Facebook is located in area with low levels of expected anonymity while Twitter is in the lower left quadrant, with high levels of anonymity and more content about public affairs; and Instagram and WhatsApp is in the lower-right quadrant, with low almost no expectation and anonymity.

4.4 Political dimension: content about public and

private topics

With respect to the type of content prevalent on the platforms about private life or public affairs, interviewees explain that when news about public affairs is shared on WhatsApp, it is between close acquaintances. Martina, a 22-year-old economist, explained: “for example, when Obama came: Did you see that tomorrow Obama is coming (to Argentina)? Did you see all the mess downtown about Obama?”16 Elsa, a 66-year-old retiree, described: “I have groups of friendly people, and then, also, we comment on the news, they send you information, that comes from Facebook, that comes from different newspapers, and well, and so on.”17

Similarly, Instagram users perceive this platform as a space for entertainment and aesthetics where political content was absent. Santiago, a 19-year-old student, remarked that “Instagram is not so politicized,”18 and Martin, a 32-year-old insurance producer said: “Instagram, although I don’t use it much, occasionally I upload something and it’s more entertainment than anything else.”19 The platform is perceived as more frivolous, with less space to post about public affairs. Maria, a 22-year-old university student, said: “I see that Instagram is more for the moment or maybe there are more beautiful photos. On the other hand, on Facebook, although photos are shared, you can write more and expand and put whatever you like, but not on Instagram”20. German, a 30-year-old lawyer, comments: “Instagram is something completely more… empty, so to speak, you post photos and nothing else and see photos, I don’t know, it is even more self-centered than what we are used to, is to see and show what you are doing”21. Micaela, a 21-communication student, said: “on Instagram I follow accounts that are interesting to me, such as clothes, or clothing brands, but also bloggers, fashion bloggers, food, travel, and then every so often I see a picture of someone I know.”22 For this reason, Instagram and WhatsApp are on the right side of the matrix, both with low levels of current affairs talk.

Twitter is in the lower left quadrant, with high levels of anonymity and more content about public affairs. Some interviewees saw Twitter as a space for political discussion, where people post opinions and discuss ideas without having to be careful. María, 22-year-old student explained: “(People use it) to insult, you post insults (on Twitter) like it was nothing because as there are so few characters maybe you can’t argue or justify why you say it and the truth is that I don’t like the idea very much.”23 In this sense, this platform is perceived as a space where people can say whatever they want, due to the character limit and the perceived aggressiveness of its culture. Isabel, a 24-year-old student, said: “Twitter seems to me the devil... Because the 140-character format is to vomit any thoughts you have.”24 However, others perceive this platform as an adequate place to exchange opinions in a relaxing way. Facundo, a 20-year-old student, reflected: “Twitter I really use it to see jokes, in addition to watching news and retweeting serious things, I also retweet football things.”25 Twitter is also seen as useful to escape the mainstream media’s political alignment, due to the greater diversity of sources. Francisco, a 32-year-old worker in tourism and insurance services, analyzed: “Twitter is the social media platforms that allows you to inform yourself and see different opinions, right? Because you can see, not only a medium that has a given political focus but also a diversity of opinions and how news is covered from different viewpoints.”26

In relation to the level of exposure seen on the personal axis, in terms of public-private content, Facebook is located at the intersection between public life and private life. Interviews indicate more caution, as users think their reputation is at stake when discussing political issues. Juana, a 20-year-old student, stated: “I will never ever comment on Facebook, or posting things that generate controversy... like football, politics, like that I avoid it because ... it generates problems, usually.”27 Luciano, a 24-year-old actor, explained: “I try not to have a very strong political profile on Facebook because political exchanges in our society are not often conducted in the best way, and not with the best arguments.”28 Users report sharing content that generates a lot of interest to them or could be useful to others and take time to craft their opinions carefully. Silvia, a 41-year-old psychologist, said: “maybe I comment when it’s something very specific. But I don’t do it all the time. Like the news, I don’t comment all the time.”29 Likewise, Malena, a 21-year-old student, analyzed: “on Facebook I have friends, family, teachers, classmates, that is, it is very broad. On the one hand you have to take care of what you publish but on the other hand it is also personal.”30

Thus, platforms are not equal or equally polarized. Some interviewees reported feeling overwhelmed by political discussions on social media. Agustina, a 33-years-old accountant, refrained from posting opinions altogether: “I do not usually share on social media because in recent years it seemed to me that sharing any news was a breeding ground for a lot of aggression. And… I didn’t like to comment or share anything.”31 Many respondents emphasize that they do not like aggressions on Facebook in relation to political content. Rosario, 32-year-old physical education professor complained “Somebody posts something in favor of Macristas and a Kirchnerist comments and they start fighting. That made me delete people from Facebook because I don’t like confrontations. A lot of fighting, and, like I say are family, that they are friends and that they fight like this? No, I don’t like it.”32 On the contrary, respondents do not report being cautious on Twitter. For those who feel comfortable with the format, Twitter is mainly used to comment on news, reality shows, football games and other topics. Micaela, a 21-year-old graphic design student, described: “I follow a radio’s or a journalist’s Twitter account and if in the morning I see that they are talking about something that interests me, they have a guest that I know or so, there I post.”33 Sandra, a 48-year-old market research company analyst, said: “on Twitter I share current affairs news that interest me (…) because I also follow many well-known journalists, I follow those people and retweet or put I like.”34 Melisa, a 21-year-old student, concurred: “Twitter is like the most politicized space I have it in my life. I follow journalists, politicians, academics who talk about politics... I don’t follow many people I know personally”.35

In sum, political discussion practices on social media vary according to evolving and shared notions of the type of content and levels of exposure on different platforms. Twitter offers anonymity while Facebook gathers diverse but potentially known audiences. Users are more cautious in their use of Facebook to maintain their own reputation. On WhatsApp or Instagram users do not need to take care their profiles in a political sense because the relationship with other users is associated with either entertainment or communication with close and familiar people, both localized in private-closeness part of the table.

5 Discussion

Our analysis shows different dynamics of political conversation across social media (Becker & Copeland 2016; Boczkowski, Matassi, & Mitchelstein, 2018; Lu & Myrick, 2016, Vaccari et al., 2015; Yamamoto, Kushin, & Dalisay 2015). We find that respondents in Argentina use platforms in diverse ways to talk about politics, economics, and current affairs. Political discussion practices vary according to shared understandings regarding the type of content and level of exposure on each platform (Schmidt, 2007), rather than according to age, gender and socio-economic status. This study indicates that political talk on social media is shaped by the political context, but also by each platform’s uptake and the overlapping of private and public, non-political, and political content in a single space (Shehata, Ekström, & Olsson, 2016). Combining in-depth interviews with a survey allows us to account both for differences in the level of political talk across platforms and for the interpretation that underlie these differences, and the practices that reify them. In the polarized Argentine context (De Luca & Malamud, 2010; Lupu et al., 2020), users employ divergent strategies to talk about politics – and refrain from doing so – on different platforms. For instance, in line with the context collapse theory (Davis & Jurgenson, 2014; Marwick & Boyd, 2014), given a perceived high level of exposure on Facebook, users tend to be more cautious, while on Twitter they express their opinions on politics more freely.

Interviewees use different social media platforms for different purposes, weighing relational and emotional matters when they select content to post on each social media platform. Consistent with Yarchi et al.’s findings in Israel (2020), another country with high levels of political polarization, users perceived Facebook as a heterogenous space, and consequently refrained from expression of political views. The link between perceived political heterogeneity and decreased political expression mirrors echoes findings by Mutz (2002) and Eveland and Hively (2009) that individuals in more heterogeneous networks are less likely to engage in public affairs.

However, network heterogeneity does not provide the full picture: some of the same respondents who chose not to talk politics on Facebook did so on Twitter. This could be explained in part by the platforms’ different affordances – for instance, Facebook requires a full name while Twitter does not – but also to their political culture. By contrast, although Instagram does not require full name registration, political talk appeared to be out of place in that platform. Finally, even though interviewees felt exposed on WhatsApp, where they tend to discuss everyday topics with friends and family, reactions to political talk varied: while some of them felt safer discussing public affairs in a relatively closed space, others felt the intrusion of politics as a violation of a private space.

These findings suggest that users focus on relational matters, rather than solely on technological affordances, to select different channels of communication. As Boczkowski proposes, individuals use diverse types of technology not in isolation but in relation to each other (2021). Thus, the fear of context collapse is different on each of the platforms. Dangerous discussion (Eveland & Hively, 2009) or incivility (Goyanes, Borah, & Zúñiga, 2021; Coe, Kenski & Rains, 2014) might not be related solely to network heterogeneity, but also to the level of exposure individuals experience when discussing politics. Whereas users appear to experience context collapse on Facebook; Twitter, Instagram and WhatsApp were perceived, for different reasons, as distinct contexts with different rules – spirited and occasionally aggressive political discussion on Twitter, no politics at all on Instagram, and cautious talk with close contacts on WhatsApp.

Our research has at least two limitations. First, although it was conducted in a polarized political context, neither the survey nor the interviews collected any information on participants or their networks’ level of polarization. Second, it relies on self-reported measures rather than on analysis of the political content posted by participants on social media. However, their perceptions of different social media platforms are valuable in and of themselves. In their study of levels of polarization on Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp, Yarchi and co-authors propose, “political polarization on social media cannot be conceptualized as a unified phenomenon” (2020, p. 2). Our paper indicates that political discussion on social media cannot be considered as a unified phenomenon either. Conceptualizing platforms as different spaces with varying cultures is key to understanding the interplay between engagement in political talk, perceived audiences, and political polarization. We hope this research is a fruitful step in that direction.

References

Anderson, A. A., Yeo, S. K., Brossard, D., Scheufele, D. A., & Xenos, M. A. (2018). Toxic talk: How online incivility can undermine perceptions of media. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 30(1), 156-168.

Aruguete, N., & Calvo, E. (2018). Time to #protest: Selective exposure, cascading activation, and framing in social media. Journal of communication, 68(3), 480-502.

Baldoni, M., & Schuliaquer, I. (2020). Los periodistas estrella y la polarización política en la Argentina. Incertidumbre y virajes fallidos tras las elecciones presidenciales. Más poder local, (40), 14-16.

Becker, A. B., & Copeland, L. (2016). Networked publics: How connective social media use facilitates political consumerism among LGBT Americans. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13(1), 22-36.

Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739-768.

Birch, S. (2020). Political polarization and environmental attitudes: a cross-national analysis. Environmental Politics, 29(4), 697-718.

Boczkowski, P. J. (2021). Abundance: On the Experience of Living in a World of Information Plenty. Oxford University Press.

Boczkowski, P. J., Matassi, M., & Mitchelstein, E. (2018). How young users deal with multiple platforms: The role of meaning-making in social media repertoires. Journal of computer-mediated communication, 23 (5), 245-259.

Boczkowski, P. J., Mitchelstein, E., & Matassi, M. (2018). “News comes across when I’m in a moment of leisure”: Understanding the practices of incidental news consumption on social media. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3523-3539.

Bode, L., Vraga, E. K., Borah, P., & Shah, D. V. (2014). A new space for political behavior: Political social networking and its democratic consequences. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 19(3), 414-429.

Boulianne, S. (2015). Social media use and participation: A meta-analysis of current research. Information, Communication & Society, 18(5), 524-538.

Boulianne, S. (2018). Twenty years of digital media effects on civic and political participation. Communication research, 47(7), 947-966.

Boynton, G. R. (2013). The political domain goes to Twitter: Hashtags, retweets and URLs. Open Journal of Political Science, 4(01), 8-15.

Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. E. (2011). “The use of Twitter hashtags in the formation of ad hoc publics”. Proceedings of the 6th European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) Conference August 25-27 2011.

Bennett, S. E., Flickinger, R. S., & Rhine, S. L. (2000). Political talk over here, over there, over time. British Journal of Political Science, 30(1), 99-119.

Caton, S., Hall, M., & Weinhardt, C. (2015). How do politicians use Facebook? An applied social observatory. Big Data & Society, 2(2), 2053951715612822.

Coe, K., Kenski, K., & Rains, S. A. (2014). Online and uncivil? Patterns and determinants of incivility in newspaper website comments. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 658-679.

Conover, P. J., & Searing, D. D. (2005). Studying ‘everyday political talk’ in the deliberative system. Acta politica, 40(3), 269-283.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage.

Costa, E. (2017). “Social Media as Practices: an Ethnographic Critique of ‘Affordances’ and ‘Context Collapse’.” Working Papers for the EASA Media Anthropology Network’s 60th E-seminar. http://www. media-anthropology. net/file/costa_socialmedia_as_practice.pdf.

Davenport, S., et al. (2014). Twitter versus Facebook: Exploring the role of narcissism in the motives and usage of different social media platforms. Computers in Human Behavior, 32, 212-220.

Davis, J. L., & Jurgenson, N. (2014). Context collapse: Theorizing context collusions and collisions. Information, Communication & Society, 17 (4), 476-485.

de Bruin, A. (2017). The New Zealand Reforms: Outcomes and New Directions. In G. Bonoli, & H. Serfati (Eds.), Labour Market and Social Protection Reforms in International Perspective (pp. 221-225). Routledge.

De Luca, M., & Malamud, A. (2010). Argentina: turbulencia económica, polarización social y realineamiento político. Revista de ciencia política (Santiago), 30 (2), 173-189.

Denzin, N. K. (1978). The Research Act New York. McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Dewey, J. (1927). The public and its problems. Holt.

Duffy, B. E., Pruchniewska, U., & Scolere, L. (2017,). Platform-specific self-branding: Imagined affordances of the social media ecology. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Social Media & Society (pp. 1-9).

Ekström, M., & Östman, J. (2015). Information, interaction, and creative production: The effects of three forms of internet use on youth democratic engagement. Communication Research, 42(6), 796-818.

Eliasoph, N. (1998). Avoiding politics: How Americans produce apathy in everyday life. Cambridge University Press.

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2011). Connection strategies: Social capital implications of Facebook-enabled communication practices. New Media & Society, 13(6), 873-892.

Eveland, W. P., & Hively, M. H. (2009). Political discussion frequency, network size, and “heterogeneity” of discussion as predictors of political knowledge and participation. Journal of Communication, 59(2), 205-224.

Filer, T., & Fredheim, R. (2017). Popular with the robots: accusation and automation in the Argentine presidential elections, 2015. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 30(3), 259-274.

Fraser, N. (1990). Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. Social Text, (25/26), 56-80.

Freedom House (2018). Argentina: Freedom on the net 2018 country report. https://freedomhouse.org/country/argentina/freedom-net/2018

Gil de Zúñiga, H., Molyneux, L., & Zheng, P. (2014). Social media, political expression, and political participation: Panel analysis of lagged and concurrent relationships. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 612-634.

Gil de Zúñiga, H., Valenzuela, S., & Weeks, B. E. (2016). Motivations for political discussion: Antecedents and consequences on civic engagement. Human Communication Research, 42(4), 533-552.

Gil de Zúñiga, H., Weeks, B., & Ardèvol-Abreu, A. (2017). Effects of the news-finds-me perception in communication: Social media use implications for news seeking and learning about politics. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 22(3), 105-123.

Gil de Zúñiga, H. G., Huber, B., & Strauss, N. (2018). Medios sociales y democracia. El Profesional de la información, 27 (6), 1172-1181.

Goyanes, M., Borah, P., & de Zúñiga, H. G. (2021). Social Media Filtering and Democracy: Effects of Social Media News Use and Uncivil Political Discussions on Social Media Unfriending. Computers in Human Behavior, 120, [106759].

Habermas, J., (1984). The theory of communicative action (Vol. 1). Beacon Press.

Habermas, J., (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. MIT Press.

Halpern, D., & Gibbs, J. (2013). Social media as a catalyst for online deliberation? Exploring the affordances of Facebook and YouTube for political expression. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 1159-1168.

Hampton, K. N., Lee, C. J., & Her, E. J. (2011). How new media affords network diversity: Direct and mediated access to social capital through participation in local social settings. New Media & Society, 13(7), 1031-1049.

Hopp, T., & Vargo, C. J. (2017). Does negative campaign advertising stimulate uncivil communication on social media? Measuring audience response using big data. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 368-377.

Huckfeldt, R. R., & Sprague, J. (1995). Citizens, politics and social communication: Information and influence in an election campaign. Cambridge University Press.

Huckfeldt, R., Johnson, P. E., Johnson, P. E., & Sprague, J. (2004). Political disagreement: The survival of diverse opinions within communication networks. Cambridge University Press.

Hsu, C., & Park, H. W. (2012). Mapping online social networks of Korean politicians. Government Information Quarterly, 29 (2), 169-181.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo/INDEC (2010). Censo 2010. https://www.indec.gob.ar/indec/web/Nivel4-Tema-2-41-135

Jung, N., Kim, Y., & De Zúniga, H. G. (2011). The mediating role of knowledge and efficacy in the effects of communication on political participation. Mass Communication and Society, 14(4), 407-430.

Karapanos, E., Teixeira, P., & Gouveia, R. (2016). Need fulfillment and experiences on social media: A case on Facebook and WhatsApp. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 888-897.

Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (2017). Personal influence: The part played by people in the flow of mass communications. Routledge.

Kessler, G., Focás, B., Zárate, J., & Feuerstein E. (2020). Los divergentes en un escenario de polarización. Un estudio exploratorio sobre los “no polarizados” en controversias sobre noticias de delitos en la televisión argentina. Revista SAAP, 14 (2), 311-340.

Kim, J., & Kim, E. J. (2008). Theorizing dialogic deliberation: Everyday political talk as communicative action and dialogue. Communication Theory, 18(1), 51-70.

Kim, Y., Hsu, S. H., & de Zúñiga, H. G. (2013). Influence of social media use on discussion network heterogeneity and civic engagement: The moderating role of personality traits. Journal of Communication, 63 (3), 498-516.

Kitzberger, P. (2012). “ La madre de todas las batallas”: el kirchnerismo y los medios de comunicación. In M. De Luca, & A. Malamud (Eds.), La política en tiempos de los Kirchner (pp. 179-192). Eudeba.

Kushin, M., & Yamamoto, M. (2010). Did social media really matter? College students’ use of online media and political decision making in the 2008 election. Mass Communication and Society, 13(5), 608-630.

Larsson, A. O., & Moe, H. (2012). Studying political microblogging: Twitter users in the 2010 Swedish election campaign. New Media & Society, 14(5), 729-747.

Lee, J. K., Choi, J., Kim, C., & Kim, Y. (2014). Social media, network heterogeneity, and opinion polarization. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 702-722.

Lee, J., & Choi, Y. (2020). Effects of network heterogeneity on social media on opinion polarization among South Koreans: Focusing on fear and political orientation. International Communication Gazette, 82(2), 119-139.

Lin, H., & Qiu, L. (2013). Two sites, two voices: Linguistic differences between Facebook status updates and tweets. International Conference on Cross-Cultural Design (pp. 432-440). Springer.

Lu, Y., & Myrick, J. G. (2016). Cross-cutting exposure on Facebook and political participation. Journal of Media Psychology, 28(3), 100-110.

Lupu, N. (2016). Latin America’s New Turbulence: The End of the Kirchner Era. Journal of Democracy, 27(2), 35-49.

Lupu, N., Oliveros, V., & Schiumerini, L. (Eds.). (2020). Campaigns and Voters in Developing Democracies: Argentina in Comparative Perspective. University of Michigan Press.

Madianou, M. (2014). Smartphones as polymedia. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(3), 667-680.

Mahoney, L. M., & Tang, T. (2016). Strategic social media: From marketing to social change. John Wiley & Sons.

Manin, B. (1987). On legitimacy and political deliberation. Political theory, 15(3), 338-368.

Mansbridge, J. (1999). Everyday talk in the deliberative system. In S. Macedo (Ed.), Deliberative Politics: Essays on Democracy and Disagreement (pp. 211-241). Oxford University Press.

Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2011). “I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately”: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114-133.

Marwick, A. E., & boyd, D. (2014). Networked privacy: How teenagers negotiate context in social media. New Media & Society, 16 (7), 1051-1067.

Matassi, M., Boczkowski, P. J., & Mitchelstein, E. (2019). Domesticating WhatsApp: Family, friends, work, and study in everyday communication. New Media & Society, 21(10), 2183-2200.

Miller, D., & Madianou, M. (2012). Should you accept a friends request from your mother? And other Filipino dilemmas. International Review of Social Research, 2(1), 9-28.

Moy, P., & Gastil, J. (2006). Predicting deliberative conversation: The impact of discussion networks, media use, and political cognitions. Political Communication, 23(4), 443-460.

Mutz, D. C. (2002). The consequences of cross-cutting networks for political participation. American Journal of Political Science, 46(4), 838-855.

O’Hara, K. P., Massimi, M., Harper, R., Rubens, S., & Morris, J. (2014). Everyday dwelling with WhatsApp. Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work (pp. 1131-1143).

Papacharissi, Z. (2009). Journalism and citizenship: new agendas in communication. Routledge.

Peng, Y. (2016). Student migration and polymedia: Mainland Chinese students’ communication media use in Hong Kong. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(14), 2395-2412.

Pingree, R. J. (2007). How messages affect their senders: A more general model of message effects and implications for deliberation. Communication Theory, 17(4), 439-461.

Portney, K. E., & O’Leary, L. (2007). Civic and Political Engagement of America’s Youth: National Survey of Civic and Political Engagement of Young People. Tisch College, Tufts University, Medford.

Quan-Haase, A., & Young, A. L. (2010). Uses and gratifications of social media: A comparison of Facebook and instant messaging. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 30(5), 350-361.

Rainie, L., Brenner, J., & Purcell, K. (2012). Photos and videos as social currency online. In Pew Research Center (Ed.), Pew Internet & American Life Project (pp. 23-29). Pew Research Center.

Renninger, B. J. (2015). Where I can be myself… where I can speak my mind: Networked counterpublics in a polymedia environment. New Media & Society, 17(9), 1513-1529.

Rodriguez, L., & Smallman, S. (2016). Political Polarization and Nisman’s Death: Competing Conspiracy Theories in Argentina. Journal of International and Global Studies 8(1), 20-39.

Scheufele, D. A. (2000). Agenda-setting, priming, and framing revisited: Another look at cognitive effects of political communication. Mass Communication & Society, 3(2-3), 297-316.

Semaan, B. C., Robertson, S. P., Douglas, S., & Maruyama, M. (2014). Social media supporting political deliberation across multiple public spheres: towards depolarization. Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work (pp. 1409-1421).

Settle, J. E. (2018). Frenemies: How social media polarizes America. Cambridge University Press.

Shehata, A., Ekström, M., & Olsson, T. (2016). Developing self-actualizing and dutiful citizens: Testing the AC-DC model using panel data among adolescents. Communication Research, 43(8), 1141-1169.

Sibona, C. (2014). Unfriending on Facebook: Context collapse and unfriending behaviors. 47th Hawaii international conference on system sciences, January 6-9, 2014 (pp. 1676-1685).

Skoric, M. M., Zhu, Q., & Pang, N. (2016). Social media, political expression, and participation in Confucian Asia. Chinese Journal of Communication, 9(4), 331-347.

Schmidt, J. (2007). Blogging practices: An analytical framework. Journal of computer-mediated communication, 12(4), 1409-1427.

Smith A., & Duggan M. (2012). Online political videos and campaign 2012. In Pew Research Center (Ed.), Pew Internet & American Life Project (pp. 1-7). Pew Research Center.

Stieglitz S. & Dang-Xuan L (2012). Social media and political communication: a social media analytics framework. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 3(4), 1277-1291.

Stier, S., Bleier, A., Lietz, H., & Strohmaier, M. (2018). Election campaigning on social media: Politicians, audiences, and the mediation of political communication on Facebook and Twitter. Political communication, 35(1), 50-74.

Trevisan, M., Vassio, L., Drago, I., Mellia, M., ... & Almeida, J. M. (2019). Towards Understanding Political Interactions on Instagram. Proceedings of the 30th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media (pp. 247-251).

Usher, N., Holcomb, J., & Littman, J. (2018). Twitter makes it worse: Political journalists, gendered echo chambers, and the amplification of gender bias. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(3), 324-344.

Vaccari, C., Valeriani, A., Barberá, P., Bonneau, R., Jost, J. T., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. A. (2015). Political expression and action on social media: Exploring the relationship between lower-and higher-threshold political activities among Twitter users in Italy. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(2), 221-239.

Valeriani, A., & Vaccari, C. (2018). Political talk on mobile instant messaging services: a comparative analysis of Germany, Italy, and the UK. Information, Communication & Society, 21 (11), 1715-1731.

Valenzuela, S., Kim, Y., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2012). Social networks that matter: Exploring the role of political discussion for online political participation. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 24(2), 163-184.

Valenzuela, S., Bachmann, I., & Bargsted, M. (2021). The personal is the political? What do Whatsapp users share and how it matters for news knowledge, polarization and participation in Chile. Digital Journalism, 9(2), 1-21.

Velasquez, A., & Rojas, H. (2017). Political expression on social media: The role of communication competence and expected outcomes. Social Media+ Society, 3 (1), 2056305117696521, p. 1-13.

Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Harvard University Press.

Vochocová, L., Štětka, V., & Mazák, J. (2016). Good girls don’t comment on politics? Gendered character of online political participation in the Czech Republic. Information, Communication & Society, 19(10), 1321-1339.

Wen, N., Xiaoming, H., & George, C. (2013). Gender and political participation: News consumption, political efficacy and interpersonal communication. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 19 (4), 124-149.

Yamamoto, M., Kushin, M. J., & Dalisay, F. (2015). Social media and mobiles as political mobilization forces for young adults: Examining the moderating role of online political expression in political participation. New Media & Society, 17(6), 880-898.

Yang, J., & Counts, S. (2010). Comparing information diffusion structure in weblogs and microblogs. Proceedings of the Fourth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (pp. 351-354).

Yarchi, M., Baden, C., & Kligler-Vilenchik, N. (2020). Political polarization on the digital sphere: A cross-platform, over-time analysis of interactional, positional, and affective polarization on social media. Political Communication, 38(1-2), 1-42.

Zhang, W., & Wang, R. (2010). Interest-oriented versus relationship-oriented social network sites in China. First Monday, 15(8).

Zhou, X., Liang, X., Zhang, H., & Ma, Y. (2015). Cross-platform identification of anonymous identical users in multiple social media networks. IEEE transactions on knowledge and data engineering, 28(2), 411-424.

Zukin, C., Keeter, S., Andolina, M., Jenkins, K., & Carpini, M. X. D. (2006). A new engagement?: Political participation, civic life, and the changing American citizen. Oxford University Press.

Funding and acknowledgements

Date received: May 2021

Date accepted: October 2021

1 Interview12/06/2017.

2 Interview 08/07/2017.

3 Interview 04/28/2016.

4 Interview 09/30/2017.

5 Interview 08/15/2016.

6 Interview 03/22/2017.

7 Interview 06/05/2017.

8 Interview 07/14/2017.

9 Interview 04/28/2016.

10 Interview 04/01/2017

11 Interview 07/07/2017.

12 Interview 11/28/2017.

13 Interview 04/17/2016.

14 Interview 08/01/2017.

15 Interview 09/10/2017.

16 Interview 03/26/2016.

17 Interview12/30/2016.

18 Interview10/13/2016.

19 Interview 03/01/2017.

20 Interview 06/24/2016.

21 Interview12/05/2016.

22 Interview 05/30/2016.

23 Interview 06/24/2016.

24 Interview 04/26/2016.

25 Interview 06/01/2017.

26 Interview 03/01/2017.

27 Interview 03/30/2016.

28 Interview 07/05/2016.

29 Interview 10/27/2016.

30 Interview 05/18/2016.

31 Interview 05/30/2017.

32 Interview 06/12/2017.

33 Interview 05/30/2016.

34 Interview 08/25/2017.

35 Interview 30/3/2016.

Metrics

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2021 Eugenia Mitchelstein, Pablo Boczkowski, Camila Giuliano (Author)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.